The State, Developers, and Urban Production in Mega Manila Gavin Shatkin, Morgan Mouton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riders Digest 2019

RIDERS DIGEST 2019 PHILIPPINE EDITION Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. OFFICES NATIONWIDE LEGEND: RLB Phils., Inc Office: • Manila • Sta Rosa, Laguna • Cebu • Davao • Cagayan de Oro • Bacolod • Iloilo • Bohol • Subic • Clark RLB Future Expansions: • Dumaguete • General Santos RIDERS DIGEST PHILIPPINES 2019 A compilation of cost data and related information on the Construction Industry in the Philippines. Compiled by: Rider Levett Bucknall Philippines, Inc. A proud member of Rider Levett Bucknall Group Main Office: Bacolod Office: Building 3, Corazon Clemeña 2nd Floor, Mayfair Plaza, Compound No. 54 Danny Floro Lacson cor. 12th Street, Street, Bagong Ilog, Pasig City 1600 Bacolod City, Negros Occidental Philippines 6100 Philippines T: +63 2 234 0141/234 0129 T: +63 34 432 1344 +63 2 687 1075 E: [email protected] F: +63 2 570 4025 E: [email protected] Iloilo Office: 2nd Floor (Door 21) Uy Bico Building, Sta. Rosa, Laguna Office: Yulo Street. Iloilo Unit 201, Brain Train Center City Proper, Iloilo, 5000 Lot 11 Block 3, Sta. Rosa Business Philippines Park, Greenfield Brgy. Don Jose, Sta. T:+63 33 320 0945 Rosa City Laguna, 4026 Philippines E: [email protected] M: +63 922 806 7507 E: [email protected] Cagayan de Oro Office: Rm. 702, 7th Floor, TTK Tower Cebu Office: Don Apolinar Velez Street Brgy. 19 Suite 602, PDI Condominium Cagayan De Oro City Archbishop Reyes Ave. corner J. 9000 Philippines Panis Street, Banilad, Cebu City, 6014 T: +63 88 8563734 Philippines M: +63 998 573 2107 T: +63 32 268 0072 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Subic Office: Davao Office: The Venue Bldg. -

Construction of up New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines

PHILIPPINE INTERNATIONAL TRADING CORPORATION National Development Company Building, 116 Tordesillas Street, Salcedo Village, 1227 Makati City CONSTRUCTION OF UP NEW CLARK CITY – PHASE 1 FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 Rebid (Previous Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2019-097) Approved Budget for the Contract: P 144,731,763.80 BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE II FEBRUARY 2020 Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID (PREVIOUS BID REF. NO. GPG-B2-2019-097) PHILIPPINE INTERNATIONAL TRADING CORPORATION National Development Company (NDC) Building, 116 Tordesillas Street, Salcedo Village, 1227 Makati City CONSTRUCTION OF UP NEW CLARK CITY – PHASE 1 FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bid Reference No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID (Previous Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2019-097) Approved Budget for the Contract: P 144,731,763.80 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I. INVITATION TO BID…………………………................. 3 SECTION II. INSTRUCTIONS TO BIDDERS………………………… 6 SECTION III. BID DATA SHEET………………………………………. 31 SECTION IV. GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT…………… 43 SECTION V. SPECIAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT…………….. 73 SECTION VI. BIDDING FORMS………………………………………... 79 SECTION VII. POST-QUALIFICATION DOCUMENTS……………….199 SECTION VIII. SAMPLE FORMS…………………………………….…..202 SECTION IX. CHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS……………………207 Page 2 of 213 Construction of UP New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. No. GPG-B2-2020-271 REBID Section I. Invitation to Bid Section I. Invitation to Bid (ITB) Page 3 of 213 Construction of UP New Clark City – Phase 1 for the University of the Philippines Philippine International Trading Corporation Bid Ref. -

Part 1 – BUSINESS and GENERAL INFORMATION Item 1

C O V E R S H E E T SEC Registration Number 1 7 0 9 5 7 C O M P A N Y N A M E F I L I N V E S T L A N D , I N C . A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S PRINCIPAL OFFICE ( No. / Street / Barangay / City / Town / Province ) 7 9 E D S A , B r g y . H i g h w a y H i l l s , M a n d a l u y o n g C i t y Secondary License Type, If Form Type Department requiring the report Applicable 1 7 - A C O M P A N Y I N F O R M A T I O N Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Number Mobile Number 7918-8188 No. of Stockholders Annual Meeting (Month / Day) Fiscal Year (Month / Day) 5,670 Every 2nd to the last Friday 12/31 of April Each Year CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number Ms. Venus A. Mejia venus.mejia@filinvestg 7918-8188 roup.com CONTACT PERSON’s ADDRESS 79 EDSA, Brgy. Highway Hills, Mandaluyong City NOTE 1 : In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated 2 : All Boxes must be properly and completely filled-up. -

Business Directory Commercial Name Business Address Contact No

Republic of the Philippines Muntinlupa City Business Permit and Licensing Office BUSINESS DIRECTORY COMMERCIAL NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTACT NO. 12-SFI COMMODITIES INC. 5/F RICHVILLE CORP TOWER MBP ALABANG 8214862 158 BOUTIQUE (DESIGNER`S G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG BOULEVARD) 158 DESIGNER`S BLVD G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG 890-8034/0. EXTENSION 1902 SOFTWARE 15/F ASIAN STAR BUILDING ASEAN DRIVE CORNER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION SINGAPURA LANE FCC ALABANG 3ARKITEKTURA INC KM 21 U-3A CAPRI CONDO WSR CUPANG 851-6275 7 MARCELS CLOTHING INC.- LEVEL 2 2040.1 & 2040.2 FESTIVAL SUPERMALL 8285250 VANS FESTIVAL ALABANG 7-ELEVEN RIZAL ST CORNER NATIONAL ROAD POBLACION 724441/091658 36764 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE EAST SERVICE ROAD ALABANG SERVICE ROAD (BESIDE STORE PETRON) 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE G/F REPUBLICA BLDG. MONTILLANO ST. ALABANG 705-5243 STORE MUNT. 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE UNIT 1 SOUTH STATION ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD 5530280 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE 452 CIVIC PRIME COND. FCC ALABANG 7-ELEVEN/FOODSTORE MOLINA ST COR SOUTH SUPERH-WAY ALABANG 7MARCELS CLOTHING, INC. UNIT 2017-2018 G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER 8128861 MUNTINLUPA CITY 88 SOUTH POINTER INC. UNIT 2,3,4 YELLOW BLDG. SOUTH STATION FILINVEST 724-6096 (PADIS POINT) ALABANG A & C IMPORT EXPORT E RODRIGUEZ AVE TUNASAN 8171586/84227 66/0927- 7240300 A/X ARMANI EXCHANGE G/F CORTE DE LAS PALMAS ALAB TOWN CENTER 8261015/09124 AYALA ALABANG 350227 AAI WORLDWIDE LOGISTICS KM.20 WEST SERV.RD. COR. VILLONGCO ST CUPANG 772-9400/822- INC 5241 AAPI REALTY CORPORATION KM22 EAST SERV RD SSHW CUPANG 8507490/85073 36 AB MAURI PHILIPPINES INC. -

IN the NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiatives Service

DATE: ____JULY _1________7, 2020 DAY: _____FRIDAY_ _______ DENR IN THE NEWS Strategic Communication and Initiatives Service STRATEGIC BANNER COMMUNICATION UPPER PAGE 1 EDITORIAL CARTOON STORY STORY INITIATIVES PAGE LOWER SERVICE July 17, 2020 PAGE 1/ DATE TITLE : DENR reaches 80% of full-year seedling target despite Covid -19 July 16, 2020, 7:19 pm MANILA – The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) on Thursday said it was able to raise some 36 million seedlings for the Enhanced National Greening Program (ENGP) during the first half of 2020 despite the coronavirus pandemic. The number already represents almost 80 percent of the 45.2 million seedlings targeted for the entire year under the government’s flagship reforestation program, DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu said in a media release, citing a report from the Forest Management Bureau (FMB). “This speaks well of how the DENR and its partners have carried out the ENGP in the face of challenges and constraints created by the pandemic,” Cimatu said. With this development, Cimatu said, the DENR is “on track” with its ENGP seedling production “just in time for planting this rainy season.” In its report, the FMB said the seedling production covers both plantation species and indigenous species used for rehabilitation of denuded areas in watershed, mangrove and protected areas. It also includes commodity species used for the establishment of agroforestry plantations. As of July 9, indigenous and plantation seedlings had reached 20 million; bamboo, 3.4 million; agroforestry, 2.98 million; fruit trees, 1.2 million; fuelwood, 796,600; rubber, 131,775; nipa, 65,000; and Ilang-ilang, 50,000. -

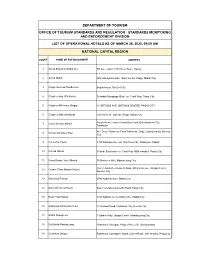

Standards Monitoring and Enforcement Division List Of

DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM OFFICE OF TOURISM STANDARDS AND REGULATION - STANDARDS MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT DIVISION LIST OF OPERATIONAL HOTELS AS OF MARCH 26, 2020, 09:00 AM NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION COUNT NAME OF ESTABLISHMENT ADDRESS 1 Ascott Bonifacio Global City 5th ave. Corner 28th Street, BGC, Taguig 2 Ascott Makati Glorietta Ayala Center, San Lorenzo Village, Makati City 3 Cirque Serviced Residences Bagumbayan, Quezon City 4 Citadines Bay City Manila Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. cor. Coral Way, Pasay City 5 Citadines Millenium Ortigas 11 ORTIGAS AVE. ORTIGAS CENTER, PASIG CITY 6 Citadines Salcedo Makati 148 Valero St. Salcedo Village, Makati city Asean Avenue corner Roxas Boulevard, Entertainment City, 7 City of Dreams Manila Paranaque #61 Scout Tobias cor Scout Rallos sts., Brgy. Laging Handa, Quezon 8 Cocoon Boutique Hotel City 9 Connector Hostel 8459 Kalayaan Ave. cor. Don Pedro St., POblacion, Makati 10 Conrad Manila Seaside Boulevard cor. Coral Way MOA complex, Pasay City 11 Cross Roads Hostel Manila 76 Mariveles Hills, Mandaluyong City Corner Asian Development Bank, Ortigas Avenue, Ortigas Center, 12 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Quezon City 13 Discovery Primea 6749 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 14 Domestic Guest House Salem Complex Domestic Road, Pasay City 15 Dusit Thani Manila 1223 Epifanio de los Santos Ave, Makati City 16 Eastwood Richmonde Hotel 17 Orchard Road, Eastwood City, Quezon City 17 EDSA Shangri-La 1 Garden Way, Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City 18 Go Hotels Mandaluyong Robinsons Cybergate Plaza, Pioneer St., Mandaluyong 19 Go Hotels Ortigas Robinsons Cyberspace Alpha, Garnet Road., San Antonio, Pasig City 20 Gran Prix Manila Hotel 1325 A Mabini St., Ermita, Manila 21 Herald Suites 2168 Chino Roces Ave. -

A Study on Dutertenomics: Drastic Policy Shift in PPP Infrastructure Development in the Philippines

投稿論文/Contributions A Study on Dutertenomics: Drastic Policy Shift in PPP Infrastructure Development in the Philippines Susumu ITO Chuo University, Tokyo, Japan Abstract This paper studies Dutertenomics of the Philippines which is regarded as drastic policy shift in PPP, Public-private partnership, infrastructure development. While Aquino administration focused on PPP-based infrastructure development as a priority policy, the Duterte administration launched "Dutertenomics", a large-scale infrastructure development plan of about 8 trillion pesos, about 160 billion USD, over 6 years in 2017 which mainly depends on national budget and ODA as financial source rather than PPP. This triggered debate of "PPP vs ODA" in the Philippines. The paper discusses PPP related policies and measures implemented by Aquino administration including government organization, project development fund, PPP fund and relaxation of single borrowers' limit. Dutertenomics will be discussed from the point of view of 1) acceleration of infrastructure development, 2) shift from PPP to ODA, 3) hybrid PPP and 4) financial sources. The paper also examines changes in infrastructure development and its policy in the three decades after Marcos administration since 1986 as a background of these policy shift. The paper discusses that the issue is not about the "PPP vs ODA" but how to promote complementary relations between the public sector and PPP; in other words “PPP and ODA”. Keyword: Public-private partnership, Infrastructure, Philippines Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... -

Issues and Directions on Integrated Public Transport in Metropolitan Manila

Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.6, 2007 ISSUES AND DIRECTIONS ON INTEGRATED PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN METROPOLITAN MANILA Noriel Christopher C. TIGLAO Ildefonso T. PATDU, Jr. Assistant Professor Director, Planning Service National College of Public Administration Department of Transportation and and Governance Communications University of the Philippines, Diliman Columbia Tower, Ortigas Avenue 1101 Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1555 Mandaluyong City, PHILIPPINES Telefax: +63-2-928-3861 Telefax: +63-2-727-7960 Email: [email protected] Email:[email protected] Abstract: The urban population of Metro Manila continues to expand along with high rates of suburbanization at adjoining municipalities. This greater metropolitan region is now referred to as 'Mega Manila'. The resulting urban pattern is one where an increasing number of people live at the fringes of the metropolitan area but still need to travel to the city centers to work or study. In order to sustain economic growth and development and to protect the environment in the region, there is a need to increase mobility through the provision of an integrated public transport system. This paper reviews the various sustainable development and management issues and policies impinging on the public transport system of Metro Manila. The paper also reviews and evaluates existing policy directions in relation to the development of an integrated public transport system for the metropolis. Key Words: integrated public transport, sustainable development, mega-city 1. INTRODUCTION The urban population of Metro Manila continues to expand along with high rates of suburbanization at adjoining municipalities. This greater metropolitan region is now referred to as 'Mega Manila'. -

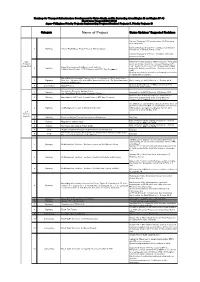

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016). -

Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, the Republic of the Philippines

Study on Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in FY2014 Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, The Republic of The Philippines Final Report February 2015 Prepared for: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Ernst & Young ShinNihon LLC Japan External Trade Organization Prepared by: TOSTEMS, Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. Japan Transportation Planning Association Reproduction Prohibited Preface This report shows the result of “Study on Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in FY2014” prepared by the study group of TOSTEMS, Inc., Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. and Japan Transportation Planning Association for Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. This study “Study on Medium Capacity Transit System Project in Metro Manila, The Republic of The Philippines” was conducted to examine the feasibility of the project which construct the medium capacity transit system to approximately 18km route from Sta. Mesa area through Mandaluyong City, Ortigas CBD and reach to Taytay City with project cost of 150 billion Yen. The project aim to reduce traffic congestion, strengthen the east-west axis by installing track-guided transport system and form the railway network with connecting existing and planning lines. We hope this study will contribute to the project implementation, and will become helpful for the relevant parties. February 2015 TOSTEMS, Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Mitsubishi Heavy -

China's Intentions

Dealing with China in a Globalized World: Some Concerns and Considerations Published by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. 2020 5/F Cambridge Center Bldg., 108 Tordesillas cor. Gallardo Sts., Salcedo Village, Makati City 1227 Philippines www.kas.de/philippines [email protected] Cover page image, design, and typesetting by Kriselle de Leon Printed in the Philippines Printed with fnancial support from the German Federal Government. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., 2020 The views expressed in the contributions to this publication are those of the individual authors and do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung or of the organizations with which the authors are afliated. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Edited by Marie Antoinette P. de Jesus eISBN: 978-621-96332-1-5 In Memory of Dr. Aileen San Pablo Baviera Table of contents i Foreword • Stefan Jost 7 1 Globality and Its Adversaries in the 21st Century • Xuewu Gu 9 Globality: A new epochal phenomenon of the 21st century 9 Understanding the conditional and spatial referentiality of globality 11 Globality and its local origins 12 Is globality measurable? 13 Dangerous adversaries of globality 15 Conclusion 18 2 China’s Intentions: A Historical Perspective • Kerry Brown 23 Getting the parameters right: What China are we talking about and in which way? 23 Contrasting -

9. Metro Manila, Philippines Theresa Audrey O

9. Metro Manila, Philippines Theresa Audrey O. Esteban and Michael Lindfield 9.1 INTRODUCTION Metro Manila, the National Capital Region of the Philippines, is the seat of government and the most populous region of the Philippines. It covers an area of more than 636 square kilometres and is composed of the City of Manila and 16 other local government units (15 cities and one municipality) (). As the city has grown, the local government structure has led to a polycentric system of highly competitive cities in the metropolitan region. The impact of rapid urbanization on the city has been dramatic. Metro Manila is the centre of culture, tourism, Figure 9.1 Map of Metro Manila the economy, education and the government of the Philippines. Its most populous and largest city in terms of land area is Quezon City, with the centre of business and financial activities in Makati (Photo 9.1). Other commercial areas within the region include Ortigas Centre; Bonifacio Global City; Araneta Centre, Eastwood City and Triangle Park in Quezon City; the Bay City reclamation area; and Alabang in Muntinlupa. Among the 12 defined metropolitan areas in the Philippines, Metro Manila is the most populous.427 It is also the 11th most populous metropolitan area in the world.428 The 2010 census data from the Philippine National Statistics Office show Metro Manila having a population almost 11.85 million, which is equivalent to 13 percent of the population of the Philippines. 429 Metro Manila ranks as the most densely populated of the metropolitan areas in the Philippines. Of the ten most populous cities in Credit: Wikipedia Commons / Magalhaes.