Irony of Fate in Selected Short Stories by Thomas Hardy”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational

1 Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational Alan Gordon Smith Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds York St John University School of Humanities, Religion and Philosophy April 2019 2 3 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alan Gordon Smith to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 4 5 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to have been in receipt of the valuable support, creative inspiration and patience of my principal supervisor Rob Edgar throughout my period of study. This has been aided by Jo Waugh’s meticulous attention to detail and vast knowledge of nineteenth-century literature and the early assistance of big Zimmerman fan JT. I am grateful to the NHS for still being on this planet, long may its existence also continue. Much thought and thanks must also go to my late, great Mother, who in the early stages of my life pushed me onwards, initially arguing with the education department of Birmingham City Council when they said that I was not promising enough to do ‘O’ levels. Tim Moore, stepson and good friend must also be thanked for his digital wizardry. Finally, I am immensely grateful to my wife Joyce for her valued help in checking all my final drafts and the manner in which she has encouraged me along the years of my research; standing right beside me as she has always done when I have faced other challenging issues. -

Wessex Tales

COMPLETE CLASSICS UNABRIDGED Thomas Hardy Wessex Tales Read by Neville Jason 1 Preface 4:04 2 An Imaginative Woman 7:51 3 The Marchmill family accordingly took possession of the house… 7:06 4 She thoughtfully rose from her chair… 6:37 5 One day the children had been playing hide-and-seek… 7:27 6 Just then a telegram was brought up. 5:31 7 While she was dreaming the minutes away thus… 6:10 8 On Saturday morning the remaining members… 5:30 9 It was about five in the afternoon when she heard a ring… 4:36 10 The painter had been gone only a day or two… 4:39 11 She wrote to the landlady at Solentsea… 6:26 12 The months passed… 5:12 13 The Three Strangers 7:58 14 The fiddler was a boy of those parts… 5:57 15 At last the notes of the serpent ceased… 6:19 16 Meanwhile the general body of guests had been taking… 5:13 17 Now the old mead of those days… 5:21 18 No observation being offered by anybody… 6:13 19 All this time the third stranger had been standing… 5:31 20 Thus aroused, the men prepared to give chase. 8:01 21 It was eleven o’clock by the time they arrived. 7:57 2 22 The Withered Arm Chapter 1: A Lorn Milkmaid 5:22 23 Chapter 2: The Young Wife 8:55 24 Chapter 3: A Vision 6:13 25 At these proofs of a kindly feeling towards her… 3:52 26 Chapter 4: A Suggestion 4:34 27 She mused on the matter the greater part of the night… 4:42 28 Chapter 5: Conjuror Trendle 6:53 29 Chapter 6: A Second Attempt 6:47 30 Chapter 7: A Ride 7:27 31 And then the pretty palpitating Gertrude Lodge… 5:02 32 Chapter 8: A Waterside Hermit 7:30 33 Chapter 9: A Rencounter 8:06 34 Fellow Townsmen Chapter 1 5:26 35 Talking thus they drove into the town. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Miroslav Kohut Gender Relations in the Narrative Organization of Four Short Stories by Thomas Hardy Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 I would like to thank Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his valuable advice during writing of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Thomas Hardy as an author ..................................................................................... 7 1.2 The clash of two worlds in Hardy‘s fiction ............................................................. 9 1.3 Thomas Hardy and the issues of gender ............................................................... 11 1.4 Hardy‘s short stories ............................................................................................. 14 2. The Distracted Preacher .............................................................................................. 16 3. An Imaginative Woman .............................................................................................. 25 4. The Waiting Supper .................................................................................................... 32 5. A Mere Interlude -

Wessex Tales

Class 5 Thomas Hardy’s Short Stories The Withered Arm The Distracted Preacher •"How I Built Myself A House" (1865) •"The Winters and the Palmleys" (1891) •"Destiny and a Blue Cloak" (1874) •"For Conscience' Sake" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Thieves Who Couldn't Stop Sneezing" (1877) •"Incident in Mr. Crookhill's Life"(1891) •"The Duchess of Hamptonshire" (1878) (collected in A Group of Noble •"The Doctor's Legend" (1891) Dames) •"Andrey Satchel and the Parson and Clerk" (1891) •"The Distracted Preacher" (1879) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"The History of the Hardcomes" (1891) •"Fellow-Townsmen" (1880) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Netty Sargent's Copyhold" (1891) •"The Honourable Laura" (1881) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames) •"On The Western Circuit" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"What The Shepherd Saw" (1881) (collected in A Changed Man and •"A Few Crusted Characters: Introduction" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Other Stories) Ironies) •"A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred and Four" (1882) (collected in Wessex •"The Superstitious Man's Story" (1891) Tales) •"Tony Kytes, the Arch-Deceiver" (1891) •"The Three Strangers" (1883) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"To Please His Wife (nl)" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid" (1883) (collected in A Changed •"The Son's Veto" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) Man and Other Stories) •"Old Andrey's Experience as a Musician" (1891) •"Interlopers at the Knap" (1884) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Our Exploits -

Autumn 2018 Journal

THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL THOMAS HARDY THE THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL VOL XXXIV VOL AUTUMN AUTUMN 2018 VOL XXXIV 2018 A Thomas Hardy Society Publication ISSN 0268-5418 ISBN 0-904398-51-X £10 ABOUT THE THOMAS HARDY SOCIETY The Society began its life in 1968 when, under the name ‘The Thomas Hardy Festival Society’, it was set up to organise the Festival marking the fortieth anniversary of Hardy’s death. So successful was that event that the Society continued its existence as an organisation dedicated to advancing ‘for the benefit of the public, education in the works of Thomas Hardy by promoting in every part of the World appreciation and study of these works’. It is a non-profit-making cultural organisation with the status of a Company limited by guarantee, and its officers are unpaid. It is governed by a Council of Management of between twelve and twenty Managers, including a Student Gerald Rickards Representative. Prints The Society is for anyone interested in Hardy’s writings, life and times, and it takes Limited Edion of 500 pride in the way in which at its meetings and Conferences non-academics and academics 1.Hardy’s Coage have met together in a harmony which would have delighted Hardy himself. Among 2.Old Rectory, St Juliot its members are many distinguished literary and academic figures, and many more 3.Max Gate who love and enjoy Hardy’s work sufficiently to wish to meet fellow enthusiasts and 4.Old Rectory, Came develop their appreciation of it. Every other year the Society organises a Conference that And four decorave composions attracts lecturers and students from all over the world, and it also arranges Hardy events featuring many aspects of Hardy’s not just in Wessex but in London and other centres. -

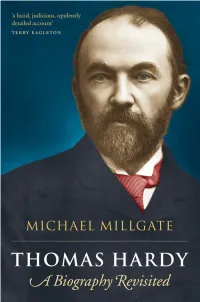

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P. -

Thomas Hardy's Vision of Wessex

Thomas Hardy’s Vision of Wessex Thomas Hardy’s Vision of Wessex Simon Gatrell University of Georgia © Simon Gatrell, 2003 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2003 978-0-333-74834-3 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-41127-6 ISBN 978-0-230-50025-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230500259 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

The Melancholy Hussar and Other Stories Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE MELANCHOLY HUSSAR AND OTHER STORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Thomas Hardy,Peter Harness | 304 pages | 01 Mar 2005 | Pan MacMillan | 9781904919506 | English | London, United Kingdom Wessex Tales - Wikipedia In , Hardy decided it was time to relinquish his architecture career and concentrate on writing full-time. In September , his first book as a full-time author, Far from the Madding Crowd, appeared serially. After publishing more than two dozen novels, one of the last being Tess of the d'Urbervilles, Hardy returned to writing poetry--his first love. From until his death, Hardy lived in Dorchester, England. Nancy Brake marked it as to-read Feb 18, Misssharice marked it as to-read Feb 26, Mohit Kumar added it Dec 20, Chantelle Belic marked it as to-read Mar 24, Snow Lu marked it as to-read Apr 05, Lena Fritz-Poncia marked it as to-read May 11, Andreas added it Dec 24, Hilary Sanchez marked it as to-read Jan 21, Deanna marked it as to-read Jan 27, Heather marked it as to-read Feb 17, Adriana marked it as to-read Feb 19, Erica Zahn marked it as to- read Feb 23, Dawn Bun is currently reading it Mar 16, Sarah K marked it as to-read Jun 28, There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Readers also enjoyed. Short Stories. About Thomas Hardy. Thomas Hardy. Thomas Hardy , OM, was an English author of the naturalist movement, although in several poems he displays elements of the previous romantic and enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural. -

1 the Conception and Birth of Wessex

Notes The reference wsCh1 etc indicates material on the book’s website; see p.viii above. 1 The Conception and Birth of Wessex 1 Michael Millgate in The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy ed Norman Page (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) p. 355. 2See wsCh1 for examples. 3 ‘Exploiting the Poor Man: The Genesis of Hardy’s Desperate Remedies’ in JEGP 94:2 (1995) 220–32. 4 For the example of The Three Tranter’s Inn, see wsCh1. 5See wsCh1 for details. 6 See Chapter 11 for a full discussion of dialect. 7 Reviews quoted in this book are taken from Hardy’s own scrapbook in the Dorset County Museum. 8See Under the Greenwood Tree ed S Gatrell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985) p. 202 for the earliest versions of Budmouth. 9 Evangeline Smith, the sister of Hardy’s friend Bosworth Smith, wrote of Hardy’s mother that ‘she rather bitterly complained of his not having kept his word to her that he would confine his productions to London, and not allow them to penetrate the all-important world of his home’. Michael Rabiger, ‘The Hoffman Papers Discovered’ The Thomas Hardy Year Book 10, p. 49. 10 It is interesting that in these two early examples the power of fate is thoroughly denied. 11 See Desperate Remedies vol. III chIV.i. 12 In Wilkinson Sherren: The Wessex of Romance (new and revised edn) (London: Francis Griffiths, 1908), there is this (p. 20): Concerning marriage, many were the curious customs observed by Wessex maidens desirous of knowing who their future husbands would be. -

Darkest Wessex: Hardy, the Gothic Short Story, and Masculinity

Darkest Wessex: Hardy, the Gothic Short Story, and Masculinity Tracy Hayes Abstract Thomas Hardy is generally recognised as a powerful delineator of the female psyche, his intuitive understanding of the emotional complexities of women such as Tess Durbeyfield and Sue Bridehead being emphasised at the expense of his male characters, who are often viewed as weak and two- dimensional. However, Hardy's men are also examined in depth, in light of their ambitions, sensitivities, hypocrisies and social expectations, thereby giving voice to discursive categories of maleness often elided in the work of his contemporaries. In the Gothic short story as featured in Blackwood’s and similar magazines, the author’s intention is to elicit terror within a circumscribed textual space, creating a balance between actuality and artifice which holds the reader enthralled. The effect is achieved through the power of brevity. In this context a withered arm, a luridly disfigured statue and a demonic fiddle player are used as vehicles by Hardy through which the incredible or fantastic highlight instances of toxic masculinity and grotesque extremes of human nature in a concentrated modality which leaves behind an indelible impression. Key Words Thomas Hardy; Gothic; masculinity; short story; periodicals; folklore. Date of Acceptance: 1 October 2020 Date of Publication: 25 October 2020 Double Blind Peer Reviewed Recommended Citation Hayes, Tracy. 2020. “Darkest Wessex: Hardy, the Gothic Short Story, and Masculinity.” Victorian Popular Fictions 2.2: 76-94. ISSN: 2632-4253 (online). DOI: https://doi.org/10.46911/NBIQ9295 Victorian Popular Fictions Volume 2: issue 2 (Autumn 2020) Darkest Wessex: Hardy, the Gothic Short Story, and Masculinity Tracy Hayes Introduction In a number of his short stories Thomas Hardy adopted the themes and signifiers of Gothic in order to explore social and psycho-sexual constructions of Victorian masculinity. -

Hardy Timeline

Thomas Hardy’s Lifeline 1840: Thomas Hardy born on June 2nd, in Higher Bockhampton. 1848: Hardy begins attending Julia Martin's school in Bockhampton. 1849: Begins playing violin locally. 1853: Hardy's education becomes intensive -- he studies Latin, French and begins reading widely. 1856: Hardy is articled to the local architect John Hicks. The office is next to Barnes' school. Around this time Hardy meets and studies with Horace Moule, going through the Greek dramatists under his tutelage. Hardy witnesses the execution of Martha Browne in August. 1862: Hardy travels to London to work under Arthur Blomfield. While finding his way in London he attends the Exhibition. He explores the cultural life of London, visiting museums, attending plays and operas, and begins writing poetry in earnest. 1865: Hardy publishes his first article, "How I Built Myself a House." 1867: Hardy returns to Dorset and works for Hicks. Hardy begins considering writing as a profession and writes the unpublished novel: The Poor Man and the Lady. 1869: Hardy works for Crickmay. 1870: Hardy travels to St. Juliot to work on the restoration of the church. Here he meets Emma Lavinia Gifford. 1871: Desperate Remedies published. 1872: Under the Greenwood Tree published. 1873: A Pair of Blue Eyes published. Hardy now relinquishes architecture as a career to write full-time. Horace Moule commits suicide in Cambridge. 1874: Far From the Madding Crowd appears serially. In September Hardy marries Emma, travels to Paris, and sets up house in London. He moves around a bit and eventually settle s in Sturminster Newton. 1876: The Hand of Ethelberta published. -

Thomas Hardy

AUTHOR DATA SHEET Macmillan Guided Readers Thomas Hardy The author and his work subjects, including Latin and Mathematics. He read as many books as he could, and he became very interested in History. When he was sixteen, Thomas left school and started to work for an architect – a man who designed new buildings and planned ways to repair old ones. Thomas loved drawing and he did it well. In 1862, Thomas moved to London. He got a job in the office of a famous architect called Arthur Blomfield. Blomfield’s office was full of interesting and well-educated young men, and Hardy enjoyed the time that he spent there. He often went to the theatre and to art exhibitions, and he went on reading as much as he could. Soon he began to write poetry, although none of it was published at this time. In 1867, Thomas decided to return to Dorchester. He still worked as an architect’s assistant, but by now he knew that he wanted to be a writer. He wrote a novel, but he could not get it published. This did not stop Thomas writing, and soon he Corbis/Betmann was working on a second novel. homas Hardy, the English novelist and poet, Twas born on 2nd June 1840, in the small village In 1870, Thomas was sent to the village of St of Higher Bockhampton. The village is in the Juliot in north Cornwall, in the far west of county of Dorset, in the southwest of England. The England. The old church in the village was in Hardy family was poor, but Thomas’s parents were very bad condition.