A Note on the Structure of Hardy's Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiny Creatures, Trophic Pyramids and Hardy's <I>The Dynasts</I>

STUDENT ESSAY COMPETITION TINY CREATURES, TROPHIC PYRAMIDS AND HARDY’S THE DYNASTS ELLE EVERHART Thomas Hardy has a tendency to focus on the small. Occasionally stopping narr- ative, he will pay detailed attention to the physical environment and the small, often unnoticed, creatures that populate it. This connection to the natural stretches across Hardy’s fiction and his poetry, including his epic verse drama The Dynasts, published in the early years of the twentieth century. Through the surrounding prose, dialogue, and the characters themselves, The Dynasts demonstrates Hardy’s assertion that the natural world is inseparable from the humans that exist within it. In this piece, I address these creatures and argue that we can read Hardy’s narratives through the ecological concept of the trophic pyramid, a hierarchy that attempts to structure energy flow through a particular ecological system. Reading Hardy’s narratives in this way allows us to envision the theoretical orientation of these creatures in relation to their human counterparts and further imagine their position in the overall structure of the narrative environment. Keywords: The Dynasts, Animal Studies, Ecology, Trophic Pyramids, Ecocriticism NSECTS AND OTHER small nonhuman animals rarely receive any critical attention. Creeping and crawling their way through any number of literary texts, I these tiny creatures remain untouched, unnoticed, and unloved. Their presence, though, reminds us of the physical earth we inhabit and the living beings we are related to, including the little animals that we (more often than not) tend to forget. Thomas Hardy’s work often pays close attention to such tiny creatures, pulling the focus away from the central human characters to examine the impact of these humans (and “the human” more generally) upon the lives of the animals that make their home in his narrative universe. -

Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational

1 Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational Alan Gordon Smith Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds York St John University School of Humanities, Religion and Philosophy April 2019 2 3 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alan Gordon Smith to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 4 5 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to have been in receipt of the valuable support, creative inspiration and patience of my principal supervisor Rob Edgar throughout my period of study. This has been aided by Jo Waugh’s meticulous attention to detail and vast knowledge of nineteenth-century literature and the early assistance of big Zimmerman fan JT. I am grateful to the NHS for still being on this planet, long may its existence also continue. Much thought and thanks must also go to my late, great Mother, who in the early stages of my life pushed me onwards, initially arguing with the education department of Birmingham City Council when they said that I was not promising enough to do ‘O’ levels. Tim Moore, stepson and good friend must also be thanked for his digital wizardry. Finally, I am immensely grateful to my wife Joyce for her valued help in checking all my final drafts and the manner in which she has encouraged me along the years of my research; standing right beside me as she has always done when I have faced other challenging issues. -

Wessex Tales

COMPLETE CLASSICS UNABRIDGED Thomas Hardy Wessex Tales Read by Neville Jason 1 Preface 4:04 2 An Imaginative Woman 7:51 3 The Marchmill family accordingly took possession of the house… 7:06 4 She thoughtfully rose from her chair… 6:37 5 One day the children had been playing hide-and-seek… 7:27 6 Just then a telegram was brought up. 5:31 7 While she was dreaming the minutes away thus… 6:10 8 On Saturday morning the remaining members… 5:30 9 It was about five in the afternoon when she heard a ring… 4:36 10 The painter had been gone only a day or two… 4:39 11 She wrote to the landlady at Solentsea… 6:26 12 The months passed… 5:12 13 The Three Strangers 7:58 14 The fiddler was a boy of those parts… 5:57 15 At last the notes of the serpent ceased… 6:19 16 Meanwhile the general body of guests had been taking… 5:13 17 Now the old mead of those days… 5:21 18 No observation being offered by anybody… 6:13 19 All this time the third stranger had been standing… 5:31 20 Thus aroused, the men prepared to give chase. 8:01 21 It was eleven o’clock by the time they arrived. 7:57 2 22 The Withered Arm Chapter 1: A Lorn Milkmaid 5:22 23 Chapter 2: The Young Wife 8:55 24 Chapter 3: A Vision 6:13 25 At these proofs of a kindly feeling towards her… 3:52 26 Chapter 4: A Suggestion 4:34 27 She mused on the matter the greater part of the night… 4:42 28 Chapter 5: Conjuror Trendle 6:53 29 Chapter 6: A Second Attempt 6:47 30 Chapter 7: A Ride 7:27 31 And then the pretty palpitating Gertrude Lodge… 5:02 32 Chapter 8: A Waterside Hermit 7:30 33 Chapter 9: A Rencounter 8:06 34 Fellow Townsmen Chapter 1 5:26 35 Talking thus they drove into the town. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Miroslav Kohut Gender Relations in the Narrative Organization of Four Short Stories by Thomas Hardy Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 I would like to thank Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his valuable advice during writing of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Thomas Hardy as an author ..................................................................................... 7 1.2 The clash of two worlds in Hardy‘s fiction ............................................................. 9 1.3 Thomas Hardy and the issues of gender ............................................................... 11 1.4 Hardy‘s short stories ............................................................................................. 14 2. The Distracted Preacher .............................................................................................. 16 3. An Imaginative Woman .............................................................................................. 25 4. The Waiting Supper .................................................................................................... 32 5. A Mere Interlude -

Thomas Hardy

THOMAS HARDY GEORGE HERBERT CLARKE "l I T HEN Thomas Hardy died last January in his quiet Dorset V V home, he passed from a countryside that had loved him companionably; from a nation which had delighted to honour him (he had r.eceived the Order of Merit in 1910, and Oxford, Cambridge and Aberdeen had given him doctorates); from a circle of famous writers who had long since acknowledged his quiet deanship; and from a whole world of thoughtful readers to whom Sue and Ethel berta and Elfride and Bathsheba and Tess, Jude and Henchard and Clym Yeobright and Gabriel Oak, had become their living fellows . 'mid this dance Of plastic circumstance. At the funeral service in Westminster Abbey the wise and the simple, high men and humble, came to do reverence to the dignity and sincerity of the life of this great genius. Sir James Barrie w,as there, who wept as he placed Mrs. Hardy's sheaf of lilies on the grave. Rudyard Kipling was there, and John Galsworthy, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Bernard Shaw, Alfred Housman, John Drinkwater and Sir Edmund Gosse. The Prime Minister was there, and Ramsay Macdonald. The dead man's nearest ones -his widow and his sister, accompanied by his old Stinsford friend and physician, Dr. Mann-were the chief mourners. The beautiful ceremony ended with the singing of Hardy's favourite hymn Lead Kindly Light-the same hymn which, sung by "the little, attenuated voices of the children", had so moved Bathsheba in Far from the Madding Crowd. The interment was over, the Dead March from Saul was played, and Hardy's ashes rested beside the other tenants of Poet's Comer. -

THOMAS HARDY the V Ariorun1 Edition OF

THE VARIORUM EDITION OF THE COMPLETE POEMS OF THOMAS HARDY THE V ariorun1 Edition OF THE Complete Poems OF THOMAS HARDY EDITED BY James Gibson M THE VARIORUM EDITION OF THE COMPLETE POEMS OF THOMAS HARDY Poems 1-919, 925--6, 929-34 and 943, Thomas Hardy's prefaces and notes © Macmillan London Ltd Poems 920-4, 927-8, 935-42 and 944-7 © Trustees of the Hardy Estate Editorial arrangement © Macmillan London Ltd 1976, 1979 Introduction and editorial matter ©James Gibson 1979 Typography © Macmillan London Ltd 1976, 1979 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1979 978-0-333-23773-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. ISBN 978-1-349-03806-0 ISBN 978-1-349-03804-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-03804-6 The Variorum Edition first published in 1979 by MACMILLAN LONDON LIMITED 4 Little Essex Street London WC2R 3LF and Basingstoke Associated companies in Delhi, Dublin, Hong Kong, johannesburg, Lagos, Melbourne, New York, Singapore and Tokyo Typeset by WESTERN PRINTING SERVICES L TO, BRISTOL Contents LIST OF MANUSCRIPT My Cicely 51 ILLUSTRATIONS page xvii Her Immortality 55 INTRODUCTION XIX The Ivy-Wife 57 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS XXXlll A Meeting with Despair 57 NOTES FOR USERS OF THE Unknowing 58 VARIORUM XXXV Friends Beyond 59 To Outer Nature 61 Domicilium 3 Thoughts of Phena 62 Middle-Age Enthusiasms 63 Wessex Poems and Other Verses In a Wood 64 Preface 6 To a Lady 65 The Temporary the All 7 To a Motherless Child 65 Amabel 8 Nature's Questioning 66 Hap 9 The Impercipient 67 In Vision I Roamed 9 At an Inn 68 At a Bridal 10 The Slow Nature 69 Postponement 11 In a Eweleaze near Weatherbury 70 A Confession to a Friend in Trouble 11 The Bride-Night Fire 71 Neutral Tones 12 Heiress and Architect 75 She at His Funeral 12 The Two Men 77 Her Initials 13 Lines 79 Her Dilemma 13 I Look Into My Glass 81 Revulsion 14 She, to Him I 14 Poems of the Past and the Present She, to Him II 15 Preface 84 She, to Him III 15 V.R. -

Wessex Tales

Class 5 Thomas Hardy’s Short Stories The Withered Arm The Distracted Preacher •"How I Built Myself A House" (1865) •"The Winters and the Palmleys" (1891) •"Destiny and a Blue Cloak" (1874) •"For Conscience' Sake" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Thieves Who Couldn't Stop Sneezing" (1877) •"Incident in Mr. Crookhill's Life"(1891) •"The Duchess of Hamptonshire" (1878) (collected in A Group of Noble •"The Doctor's Legend" (1891) Dames) •"Andrey Satchel and the Parson and Clerk" (1891) •"The Distracted Preacher" (1879) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"The History of the Hardcomes" (1891) •"Fellow-Townsmen" (1880) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Netty Sargent's Copyhold" (1891) •"The Honourable Laura" (1881) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames) •"On The Western Circuit" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"What The Shepherd Saw" (1881) (collected in A Changed Man and •"A Few Crusted Characters: Introduction" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Other Stories) Ironies) •"A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred and Four" (1882) (collected in Wessex •"The Superstitious Man's Story" (1891) Tales) •"Tony Kytes, the Arch-Deceiver" (1891) •"The Three Strangers" (1883) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"To Please His Wife (nl)" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) •"The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid" (1883) (collected in A Changed •"The Son's Veto" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies) Man and Other Stories) •"Old Andrey's Experience as a Musician" (1891) •"Interlopers at the Knap" (1884) (collected in Wessex Tales) •"Our Exploits -

Thomas Hardy S Epic-Drama: a STUDY of the DYNASTS

Thomas Hardy s Epic-Drama: A STUDY OF THE DYNASTS by Harold Orel UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PUBLICATIONS HUMANISTIC STUDIES, NO. 36 LAWRENCE, KANSAS UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS ^PUBLICATIONS HUMANISTIC STUDIES^ NO. 36 THOMAS HARDY'S EPIC-DRAMA: A STUDY OF THE DYNASTS THOMAS HARDY'S EPIC-DRAMA: A STUDY OF THE DYNASTS by Harold Orel UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PUBLICATIONS LAWRENCE, 1963 © COPYRIGHT 1963 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PRESS L. C. C. C Number 63-63211 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PRESS LAWRENCE, KANSAS TO M. D. W. Preface THIS BOOK was written because of my admiration for Thomas Hardy's The Dynasts, and because of my feeling that the last word has not yet been said about it. What I want to do is reemphasize the meaning behind Hardy's descriptive epithet, "epic-drama," To that end, I have retraced Hardy's career up to the moment he renounced the writing of novels and became a full-time poet. Poetry, for Hardy, was always the highest form of art; it was the kind of literature he wanted most to create. For years he had been contemplating a large work, a poem on the epic scale, which he needed time to write. It may be no exaggeration to say that his entire life led up to The Dynasts, and that for him it represented the supreme artistic work of his career. Since The Dynasts has often been considered primarily in terms of its philosophy, although Hardy declared vehemently on several occasions that his poem should be judged on artistic grounds, it has seemed worthwhile to reexamine the views that Hardy held on the nature of the universe and whatever gods exist. -

Autumn 2018 Journal

THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL THOMAS HARDY THE THE THOMAS HARDY JOURNAL VOL XXXIV VOL AUTUMN AUTUMN 2018 VOL XXXIV 2018 A Thomas Hardy Society Publication ISSN 0268-5418 ISBN 0-904398-51-X £10 ABOUT THE THOMAS HARDY SOCIETY The Society began its life in 1968 when, under the name ‘The Thomas Hardy Festival Society’, it was set up to organise the Festival marking the fortieth anniversary of Hardy’s death. So successful was that event that the Society continued its existence as an organisation dedicated to advancing ‘for the benefit of the public, education in the works of Thomas Hardy by promoting in every part of the World appreciation and study of these works’. It is a non-profit-making cultural organisation with the status of a Company limited by guarantee, and its officers are unpaid. It is governed by a Council of Management of between twelve and twenty Managers, including a Student Gerald Rickards Representative. Prints The Society is for anyone interested in Hardy’s writings, life and times, and it takes Limited Edion of 500 pride in the way in which at its meetings and Conferences non-academics and academics 1.Hardy’s Coage have met together in a harmony which would have delighted Hardy himself. Among 2.Old Rectory, St Juliot its members are many distinguished literary and academic figures, and many more 3.Max Gate who love and enjoy Hardy’s work sufficiently to wish to meet fellow enthusiasts and 4.Old Rectory, Came develop their appreciation of it. Every other year the Society organises a Conference that And four decorave composions attracts lecturers and students from all over the world, and it also arranges Hardy events featuring many aspects of Hardy’s not just in Wessex but in London and other centres. -

Irony of Fate in Selected Short Stories by Thomas Hardy”

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Irony of Fate in Selected Short Stories by Thomas Hardy” Verfasserin Magdalena Riegler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Jänner 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 344 353 Studienrichtung: Lehramtsstudium UF Englisch/ UF Spanisch Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Franz-Karl Wöhrer HINWEIS Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin oder der betreffende Kandidat befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbstständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der/des Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Die Habilitierten des Instituts für Anglistik und Amerikanistik bitten diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I confirm to have conceived and written this M.A. thesis in English all by myself. Quotations from other authors are all clearly marked and acknowledged in the bibliographical references, either in the footnotes or within the text. Any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the works of other authors have been truthfully acknowledged and identified in the footnotes. Signature Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. IRONY ................................................................................................................... -

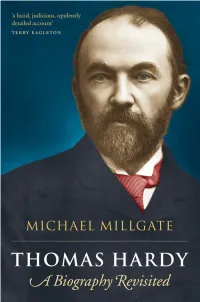

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P. -

Thomas Hardy's Vision of Wessex

Thomas Hardy’s Vision of Wessex Thomas Hardy’s Vision of Wessex Simon Gatrell University of Georgia © Simon Gatrell, 2003 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2003 978-0-333-74834-3 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-41127-6 ISBN 978-0-230-50025-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230500259 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.