What Is Left of Palestine's Eighty-Year-Old Partition Plan?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

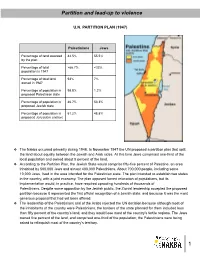

Partition and Lead-Up to Violence

P artition and leadup to violence U.N. PARTITION PLAN (1947) Palestinians Jews Percentage of land awarded 44.5% 55.5% by the plan Percentage of total >66.7% <33% population in 1947 Percentage of total land 93% 7% owned in 1947 Percentage of population in 98.8% 1.2% proposed Palestinian state Percentage of population in 46.7% 53.3% proposed Jewish state Percentage of population in 51.2% 48.8% proposed Jerusalem enclave ❖ The Nakba occurred primarily during 1948. In November 1947 the UN proposed a partition plan that split the land about equally between the Jewish and Arab sides. At this time Jews comprised onethird of the local population and owned about 5 percent of the land. ❖ According to the Partition Plan, the Jewish State would comprise fiftyfive percent of Palestine, an area inhabited by 500,000 Jews and almost 400,000 Palestinians. About 700,000 people, including some 10,000 Jews, lived in the area intended for the Palestinian state. The plan intended to establish two states in the country, with a joint economy. The plan opposed forced relocation of populations, but its implementation would, in practice, have required uprooting hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Despite some opposition by the Jewish public, the Zionist leadership accepted the proposed partition because it represented the first official recognition of a Jewish state, and because it was the most generous proposal that had yet been offered. ❖ The leadership of the Palestinians and of the Arabs rejected the UN decision because although most of the inhabitants of the country were Palestinians, the borders of the state planned for them included less than fifty percent of the country’s land, and they would lose most of the country’s fertile regions. -

The American Politics of a Jewish Judea and Samaria Rebekah Israel Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 12-6-2013 The American Politics of a Jewish Judea and Samaria Rebekah Israel Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI13120616 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Israel, Rebekah, "The American Politics of a Jewish Judea and Samaria" (2013). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 999. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/999 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE AMERICAN POLITICS OF A JEWISH JUDEA AND SAMARIA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Rebekah Israel 2013 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Rebekah Israel, and entitled The American Politics of a Jewish Judea and Samaria, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ John F. Stack _______________________________________ Nicol C. Rae _______________________________________ Nathan Katz _______________________________________ Richard S. Olson, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 14, 2013 The dissertation of Rebekah Israel is approved. _______________________________________ Dean Kenneth G. -

Britain in Palestine (1917-1948) - Occupation, the Palestine Mandate, and International Law

ARTICLES & ESSAYS https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2531-6133/7663 Britain in Palestine (1917-1948) - Occupation, the Palestine Mandate, and International Law † PATRICK C. R. TERRY TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction; 2. The Balfour Declaration; 2.1. The Letter; 2.2. Background; 2.3. Controversies Surrounding the Balfour Declaration; 2.3.1. The “Too Much Promised” Land; 2.3.1.1. Sykes-Picot-Agreement (1916); 2.3.1.2. Mcmahon- Hussein Correspondence (1915/1916); 2.3.2. International Legal Status of the Balfour Declaration; 2.3.3. Interpretation of The Text; 3. British Occupation of Palestine (1917- 1923); 4. The Palestine Mandate; 4.1. The Mandates System; 4.1.1. Self-Determination and President Wilson; 4.1.2. Covenant of The League of Nations; 4.1.2.1. Article 22; 4.1.2.2. Sovereignty; 4.1.2.3. Assessment; 4.1.3. President Wilson’s Concept of Self- Determination and The Covenant; 4.2. The Palestine Mandate in Detail; 4.2.1. First Decisions; 4.2.2. Turkey; 4.2.3. The Mandate’s Provisions; 4.2.4. The Mandate’s Legality; 4.2.4.1. Self-Determination; 4.2.4.2. Article 22 (4) Covenant of The League of Nations; 4.2.4.3. Other Violations of International Law; 5. Conclusion. ABSTRACT: At a time when there are not even negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians in order to resolve their longstanding dispute, this article seeks to explain the origins of the conflict by examining Britain’s conduct in Palestine from 1917-1948, first as an occupier, then as the responsible mandatory, under international law. -

The British Mandate: Defining the Legality of Jewish Sovereignty Over Judea and Samaria Under International Law

THE BRITISH MANDATE: DEFINING THE LEGALITY OF JEWISH SOVEREIGNTY OVER JUDEA AND SAMARIA UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW KAREN STAHL-DON MA,LLM JERUSALEM, 2017 THE BRITISH MANDATE: DEFINING THE LEGALITY OF JEWISH SOVEREIGNTY OVER JUDEA AND SAMARIA UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report is to present a clear solid historical and legal basis for Israeli sovereignty over the entire area of the Mandate. An objective evaluation of the relevant binding instruments and applicable rules of international law conclusively establishes the legality of Israeli sovereignty over Judea and Samaria,1 and the right of Jewish settlement therein. These basic legal historical documents speak the truth to all who choose to read them. It is common to analyze the legality of Jewish settlement in Judea and Samaria beginning in 19472 or in 1967 with the Six-Day War. Yet either starting point obscures the entire World War I era, which defined the framework of the region and Israel's legal claim of sovereignty over Judea and Samaria. Failure to ______________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The proper name for these territories deserves a brief discussion. "Judea and Samaria" denote the Biblical names of the area commonly referred to today as the "West Bank." These names have historically been used to describe the region that Jordan illegally held from 1949-1967. Both the Palestine Mandate and the United Nations employed the terms "Judea and Samaria" to depict this geographic region – for example, United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181 utilizes these terms in Part II(A). After conquering this territory in 1949, Jordan renamed this area the "West Bank," since the territory lies on the west bank of the Jordan River. -

Outline of the History and Status of Judea and Samaria (The West Bank) Brief Summary Judea and Samaria Were a Central Part of Th

Outline of the History and Status of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank) Brief summary Judea and Samaria were a central part of the historic homeland of the Jewish people1 from 1200 BC onwards. During a period spanning more than 1,000 years the Jewish people settled the land and established governmental and religious institutions. Although largely expelled during the Roman period2, and although the territory was renamed Palestina by the Romans, the Jewish people never abandoned their claim and intention to return to their historic homeland. In the centuries prior to 1918, and after a succession of other rulers, the area was part of the Turkish Empire. Following Turkey’s defeat in the First World War, the vast majority of its former territory in the Middle East was allocated for the creation of new Arab States under Mandates adopted by the League of Nations, the forerunner of the UN. At the same time, the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine recognised the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, allocated the territory of Palestine between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean for the purpose of reconstituting a national home for the Jewish people, and entrusted the UK as mandatory to put this into effect. In particular, the administration of Palestine was required by the Mandate to facilitate Jewish settlement throughout this territory. The rights of the Jewish people recognised in the League of Nations Mandate were preserved by Article 80 of the UN Charter, which has been accepted by all members of the UN. Israel declared its independence in 1948 on the departure of British forces, without determining its boundaries. -

The Historiography of Israel's New Historians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives The Historiography of Israel’s New Historians; rewriting the history of 1948 By Tor Øyvind Westbye Master Thesis in History Autumn 2012 The Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion – AHKR 1 To Marie 2 Acknowledgments In writing this master thesis, I have received help and guidance from a number of individuals. Most importantly, my supervisor Professor Anders Bjørkelo at the University of Bergen has kindly guided me through the process of developing a master thesis. Also important are the help and guidance offered to me by Professor Knut Vikør, also at the University of Bergen. The feedback from my fellow Middle East students at the master seminar has been equally appreciated, as well as the support given by Anne Katrine Bang who supervised my Bachelor-paper and also helped me getting started as a master student. Thank you all. Special thanks goes to Professor Avi Shlaim at St. Anthony’s College in Oxford, who gave me an invaluable understanding of the New Historiography in an interview in May 2012, and received me as a welcome guest at his office. Without his contribution this master thesis would not be half of what it is. Finally, I would like to thank my wife of six years Marie, for her unrelenting patience and understanding. This would not have been possible without your support and motivation. 3 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 Chapter 1: Historical Background ............................................................................... 9 Chapter 2: Israeli Historiography .............................................................................. 15 The Zionist historiography .................................................................................... -

The Balfour Lens

1 The Balfour Lens Palestine . is in constant danger of conflagration. Sparks are flying over its borders all the time and it may be that on some unexpected day a firewill be started that will sweep ruthlessly over this land. — Dispatch from Otis Glazebrook, U.S. consul general in Jerusalem, December 1919 In April 1922, the Foreign Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives convened a rather remarkable hearing to debate a joint congressional resolution endorsing the Balfour Declaration.1 A little over four years earlier, in November 1917, Britain’s foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, had put the weight of the British Empire behind the creation of “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, with the stipulation “that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non- Jewish communities in Palestine.” Palestine was then part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire; it came under British control following World War I, formalized in 1923 as a League of Nations mandate. As in other parts of the Levant (including Syria), however, Arabs, who then made up more than 90 percent of Palestine’s population, also hoped for in de pen dence. 17 02-3155-9-ch02.indd 17 01/14/19 2:50 pm 18 BLIND SPOT Ten outside witnesses were called to testify at the four- day hearing, including Fuad Shatara and Selim Totah, two Palestine- born U.S. citizens who spoke against the resolution and were the last witnesses to address the committee. “This is our national home, the national home of the Palestinians,” said Shatara, a Brooklyn surgeon and native of Jaffa, “and I think those people are entitled to priority as the national home of the Palestinians and not aliens who have come in and have gradually become a majority.”2 Totah, a young law student originally from Ramallah, attempted a less confrontational approach: “You gentlemen and your forefathers have fought for the idea, and that is taxation with repre sen ta tion. -

White Paper of 1939 Mideast Web Historical Documents the British White Paper of 1939

12/18/2014 MidEast Web - White Paper of 1939 MidEast Web Historical Documents The British White Paper of 1939 Middle East news peacewatch top stories books history culture dialog links Encyclopedia donations Introduction The British White Paper of 1939 was issued to satisfy mounting Arab pressure against further Jewish immigration to Palestine. Violent Arab opposition to the Mandate and Jewish settlement had begun as early as 1919, and took the form of periodic pogroms and agitation for return of Palestine to Syria. In Easter 1920, Amin El Husseini and Aref el Aref, led a particularly violent pogrom in Jerusalem. In later years the British gave Husseini the office of Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, while Aref el Aref was to write a history after the 1948 war. In 1929 there were further Arab riots in Hebron and Jerusalem. Simultaneously with the HopeSimpson report and based on its recommendations the British responded with the Passfield White Paper of 1930, which was the first attempt to limit Jewish immigration to Palestine. The Passfield White Paper evoked considerable opposition from the Zionist movement and was rescinded effectively in a letter issued to Haim Weizmann by PM Ramsay Macdonald. The renewal and increase in Jewish immigration however, soon provoked fresh trouble. In 1936 there were widespread riots in Palestine, owing partly to Arab dissatisfaction with Jewish immigration, and also to rivalry between various Palestinian families. The Peel Commission of 1937, sent to investigate the causes of the unrest, resulted in a report and White Paper recommending a second partition of Palestine, leaving a very small area for Jewish settlement. -

Peel Commission) Report - League of Nations/Non-UN Document (30 November 1937)

Plan of partition - Summary of the UK Palestine Royal Commission (Peel Commission) report - League of Nations/Non-UN document (30 November 1937) Question of Palestine home || Permalink || About UNISPAL || Search See also: Full report Follow UNISPAL RSS Twitter "As is" reference - not a United Nations document Source: League of Nations 30 November 1937 C.495.M.336.1937.VI. Geneva, November 30th, 1937. LEAGUE OF NATIONS MANDATES P A L E S T I N E -------- REPORT of the PALESTINE ROYAL COMMISSION presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to the United Kingdom Parliament by Command of His Britannic Majesty (July 1937) Distributed at the request of the United Kingdom Government. Series of League of Nations Publications VI. A. MANDATES 1937. VI A. 5 OFFICIAL COMMUNIQUE IN 9/37 PALESTINE Royal Commission 1 Plan of partition - Summary of the UK Palestine Royal Commission (Peel Commission) report - League of Nations/Non-UN document (30 November 1937) ---------- SUMMARY OF REPORT SUMMARY OF THE REPORT OF THE PALESTINE ROYAL COMMISSION. The Members of the Palestine Royal Commission were :- Rt. Hon. EARL PEEL, G.C.S.I., G.B.E. (Chairman). Rt. Hon. Sir HORACE RUMBOLD, Bart., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., M.V.O. (Vice-Chairman). Sir LAURIE HAMMOND, K.C.S.I., C.B.E. Sir MORRIS CARTER, C.B.E. Sir HAROLD MORRIS, M.B.E., K.C. Professor REGINALD COUPLAND, C.I.E. Mr. J. M. MARTIN was Secretary. _________ The Commission was appointed in August, 1936, with the following terms of reference :- To ascertain the underlying causes of the disturbances which broke -

Khalil Totah: the Unknown Years Needed Leader

Khalil Totah: During an educational career of about The Unknown twenty-five years [1919-44] with and for the Arabs, I was overwhelmed with the political, Years economic, and social problems confronting them. Having known America and the West, Thomas M. Ricks I was consumed with the passion of doing my part towards the creation of a new Arab World.1—Khalil Totah Except for the memory of Khalil Totah as the six-year principal (1919-25) of the prestigious British Mandate’s Men’s Education Training College [MTC], later known as the Kuliyyah al-‘Arabiyya, or the Government Arab College in Jerusalem,2 and his 18 years (1927-44) as a teacher and the principal of one of Mandate Palestine’s academically successful mission schools, the Friends Boys School (FBS) of Ramallah, there is surprisingly little known or written Khalil Totah, in his Ottoman soldier’s about him.3 The FBS students, teachers, uniform, April 1914. Source: T. Ricks and administrators today are reminded of Jerusalem Quarterly 34 [ 51 ] Khalil Totah every time they enter ‘Khalil Totah Hall’ for convocations, theatrical performances, and graduation exercises on the present campus of FBS or, by chance, notice Totah’s bust in the school’s library. Secondly, we know that he testified in January 1937 before the Royal Peel Commission in Jerusalem, and later in January 1946, before the equally well-known Anglo-American Commission Inquiry into Palestine in Washington, D.C. In addition, he authored and co-authored eight books in English and Arabic on education, history, and geography in -

Disorderly Decolonization: the White Paper of 1939 and the End of British Rule in Palestine

Copyright by Lauren Elise Apter 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Lauren Elise Apter Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Disorderly Decolonization: the White Paper of 1939 and the End of British Rule in Palestine Committee: Wm. Roger Louis, Supervisor Judith Coffin Yoav Di-Capua Karen Grumberg Abraham Marcus Gail Minault Disorderly Decolonization: the White Paper of 1939 and the End of British Rule in Palestine by Lauren Elise Apter, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication For the next generation Acknowledgements First and foremost I thank my father and mother, J. Scott and Ruth Apter, for their constant support. My sisters Molly Georgakis and Katherine Rutherford, and their husbands Angelo and Tut, have provided encouragement and priceless humor. Thank you, Katie, for all of the maps included here. Over the years I have been rich in mentors. They include: Esther Raizen, Sharon Muller, Ann Millin, Judith Coffin, and, for the last six years, Wm. Roger Louis. They have enriched my understanding of the past while teaching me by example how to appreciate the present. My cohorts in British Studies, History, and Hebrew have made it a pleasure to study at the University of Texas. May we remain friends well beyond this stage. This work was supported at Texas by a Donald D. Harrington Doctoral Fellowship, and by grants from Middle Eastern Studies, History, British Studies, and the Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies.