JMWP 09 Barnidge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07101944 NZO.Pd

... - ~ ~ ..... ADDRESS REPLY TO •• •• -rHIE ATTORNEY GENERAL" AND REFER TO INITIALS AND NUMIlER DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE LAK~'JMM/LN WASHINGTON, D. C. ~ ~Q JUL 1. 0 1944 Yo' '8' j = MEMORANDL1M FOR LAURENCE A. KNAPP CHIEF J FOREIGN AGENTS REGISTRATION SECTION Re: New Zioni~t Organization of America I. Identification The New Zionist Organization of America (55 West 42nd Street, New York City) is the official society in this country of Revisionist Zionists. It is affiliated to a number of similar groups using the name of the New Zionist Organization and working in other countries, and its relationship to the world New Zionist Organization will be discussed in some detail below. Among the officials of the New Zionist Organization of America are: President - Col. Morris J. Mendelsohn Chairman of the Executive Board - B. Netanyahu 'Executive Secretary - Joseph Beder . ., .. - Treasurer - L:>uis Germain~-"'·.J ,- ~.," r-~.. --- \ L.. t:.. \;-. , 'The members!rl,p of the American organization does nOi,\excfd 'one tho.and persons and is pro~1.Y' not more than 500 •., r::~V ,,( " _.~.~t~~, )'0- 'J7;r. ~~~ II. World Organization A. History ~'\\~ ~TERNAL , SEQ.umn. ,.QJ& C",O If 'flO ENIltAu~. (> , -' •• •• - 2 Zionism. Each of these movements have a cormnon aim - the estab lishment of a Jewish political state in Palestine. They differ from each other in the methods which they plan to use for the accomplishment of this aim, and. in the type of membership from which they get support. The first three movements have combined to form the World Zionist Organization. ~~l~ The fourth movement, that of the Revisionist Zionists, although affiliated to the World Zionist Organization for a short period, finally formed an independent structure called the New Zionist Organization in 1935. -

Re-Visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2016 Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine Gabriel Healey Brown Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Brown, Gabriel Healey, "Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine" (2016). Honors Papers. 226. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/226 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contested Land, Contested Representations: Re-visiting the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939 in Palestine Gabriel Brown Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Zeinab Abul-Magd Spring/2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………...1 Map of Palestine, 1936……………………………………………………………………………2 Glossary…………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter One……………………………………………………………………………………...15 Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………………...25 Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………………….37 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….50 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………. 59 Brown 1 Acknowledgements Large research endeavors like this one are never undertaken alone, and I would be remiss if I didn’t thank the many people who have helped me along the way. I owe a huge debt to Shelley Lee, Jesse Gamoran, Gavin Ratcliffe, Meghan Mette, and Daniel Hautzinger, whose kind feedback throughout the year sharpened my ideas and improved the coherence of my work more times than I can count. A special thank you to Sam Coates-Finke and Leo Harrington, who were always ready to listen as I worked through the writing process. -

The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967

Yfaat Weiss Sovereignty in Miniature: The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967 Abstract: Contemporary scholarly literature has largely undermined the common perceptions of the term sovereignty, challenging especially those of an exclusive ter- ritorial orientation and offering a wide range of distinct interpretations that relate, among other things, to its performativity. Starting with Leo Gross’ canonical text on the Peace of Westphalia (1948), this article uses new approaches to analyze the policy of the State of Israel on Jerusalem in general and the city’s Mount Scopus enclave in 1948–1967 in particular. The article exposes tactics invoked by Israel in three different sites within the Mount Scopus enclave, demilitarized and under UN control in the heart of the Jordanian-controlled sector of Jerusalem: two Jewish in- stitutions (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah hospital), the Jerusa- lem British War Cemetery, and the Palestinian village of Issawiya. The idea behind these tactics was to use the Demilitarization Agreement, signed by Israel, Transjor- dan, and the UN on July 7, 1948, to undermine the status of Jerusalem as a Corpus Separatum, as had been proposed in UN Resolution 181 II. The concept of sovereignty stands at the center of numerous academic tracts written in the decades since the end of the Cold War and the partition of Europe. These days, with international attention focused on the question of Jerusalem’s international status – that is, Israel’s sovereignty over the town – there is partic- ularly good reason to examine the broad range of definitions yielded by these discussions. Such an examination can serve as the basis for an informed analy- sis of Israel’s policy in the past and, to some extent, even help clarify its current approach. -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

Urban Arab Palestine, No-Go Areas, and the Conflicted Course of British Counter-Insurgency During the Great Rebellion, 1936–1939

Chapter 6 “Government Forces Dare Not Penetrate”: Urban Arab Palestine, No-Go Areas, and the Conflicted Course of British Counter-Insurgency during the Great Rebellion, 1936–1939 Simon Davis The Great Palestine Arab rebellion against British rule, sometimes termed the first authentic intifada,1 lasted from April 1936 until summer 1939. The British Mandate’s facilitation of Zionist expansion in Palestine had since the 1920s recurrently aroused violent Arab protest, mainly at urban points of interface with Jewish communities. Initially, the great rebellion seemed just such an- other occurrence, beginning with inter-communal riots in Manshiyeh, the mixed Arab-Jewish workers’ suburb separating the Jewish city of Tel Aviv from its mainly Arab neighbor Jaffa. But despite the reinforcement of exhausted Palestine Police with 300 Cameron Highlanders, a quarter of the infantry in Palestine, the disorders metamorphosed into lasting, territory-wide Arab civil disobedience. Coordinated by National Committees in each principal town, elite leaders hurriedly formed the Jerusalem-based Arab Higher Committee, hoping to preserve leadership over qualitatively new levels of nationally con- scious activism. Proliferating rural sniping and sabotage, mainly on Jewish settlements, most engaged the British military, predisposed to familiar small- war, anti-banditry traditions, largely derived from experience in India. But urban political violence, mainly in the form of reciprocally escalating Arab and Jewish bombings, shootings and stabbings, was left to the increasingly over- whelmed police. Consequent loss of control over Arab towns forced the British High Commissioner, Sir Arthur Wauchope, to invoke emergency regulations in June 1936. But subsequent military repression, frequently contemptuous of civil political context, merely aggravated Arab resistance, which was trans- formed, British observers noted, from past patterns of spasmodic anti-Zionist violence into a comprehensive uprising against British Mandatory rule itself. -

As Mirrored in This Volume of His Letters, the Years 1937-38 Were For

THE LETTERS AND PAPERS OF CHAIM WEIZMANN January 1937 – December 1938 Volume XVIII, Series A Introduction: Aaron Klieman General Editor Barnet Litvinoff, Volume Editor Aaron Klieman, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1979 [Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel, by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org.] As mirrored in this volume of his letters, the years 1937-38 were for Chaim Weizmann the most critical period of his political life since the weeks preceding the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in November 1917. We observe him at the age of 64 largely drained of physical strength, his diplomatic orientation of collaboration with Great Britain under attack, and his leadership challenged by a generation of younger, militant Zionists. In his own words he was 'a lonely man standing at the end of a road, a via dolorosa. I have no more courage left to face anything—and so much is expected from me.' This situation found its prelude in 1936, when Arab unrest compelled the British Government to undertake a comprehensive reassessment of its policy in Palestine. A Royal Commission headed by Lord Peel was charged with investigating the causes of the disturbances. Weizmann, alert to the implications, took great pains to ensure that the Zionist case was presented with the utmost cogency. As President of the Zionist Organization and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, he delivered the opening statement on behalf of the Jews to the Royal Commission in Jerusalem on 25 November 1936. He subsequently gave evidence four times in camera, and directed the presentation of evidence by other Zionist witnesses and maintained informal contact with members of the Commission. -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

JABOTINSKY on CANADA and the Unlted STATES*

A CASE OFLIMITED VISION: JABOTINSKY ON CANADA AND THE UNlTED STATES* From its inception in 1897, and even earlier in its period of gestation, Zionism has been extremely popular in Canada. Adherence to the movement seemed all but universal among Canada's Jews by the World War I era. Even in the interwar period, as the flush of first achievement wore off and as the Canadian Jewish community became more acclimated, the movement in Canada functioned at a near-fever pitch. During the twenties and thirties funds were raised, acculturatedJews adhered toZionism with some settling in Palestine, and prominent gentile politicians publicly supported the movement. The contrast with the United States was striking. There, Zionism got a very slow start. At the outbreak of World War I only one American Jew in three hundred belonged to the Zionist movement; and, unlike Canada, a very strong undercurrent of anti-Zionism emerged in the Jewish community and among gentiles. The conversion to Zionism of Louis D. Brandeis-prominent lawyer and the first Jew to sit on the United States Supreme Court-the proclamation of the Balfour Declaration, and the conquest of Palestine by the British gave Zionism in the United States a significant boost during the war. Afterwards, however, American Zionism, like the country itself, returned to "normalcy." Membership in the movement plummeted; fundraising languished; potential settlers for Palestine were not to be found. One of the chief impediments to Zionism in America had to do with the nature of the relationship of American Jews to their country. Zionism was predicated on the proposition that Jews were doomed to .( 2 Michuel Brown be aliens in every country but their own. -

Britain's Broken Promises: the Roots of the Israeli and Palestinian

Britain’s Broken Promises: The Roots of the Israeli and Palestinian Conflict Overview Students will learn about British control over Palestine after World War I and how it influenced the Israel‐Palestine situation in the modern Middle East. The material will be introduced through a timeline activity and followed by a PowerPoint that covers many of the post‐WWI British policies. The lesson culminates in a letter‐writing project where students have to support a position based upon information learned. Grade 9 NC Essential Standards for World History • WH.1.1: Interpret data presented in time lines and create time lines • WH.1.3: Consider multiple perspectives of various peoples in the past • WH.5.3: Analyze colonization in terms of the desire for access to resources and markets as well as the consequences on indigenous cultures, population, and environment • WH.7.3: Analyze economic and political rivalries, ethnic and regional conflicts, and nationalism and imperialism as underlying causes of war Materials • “Steps Toward Peace in Israel and Palestine” Timeline (excerpt attached) • History of Israel/Palestine Timeline Questions and Answer Key, attached • Drawing paper or chart paper • Colored pencils or crayons (optional) • “Britain’s Broken Promises” PowerPoint, available in the Database of K‐12 Resources (in PDF format) o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to -

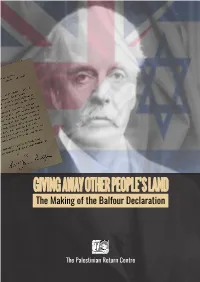

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 12 May 2006 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Ismael, T. Y. (2002) 'Arafat's Palestine national authority.', Working Paper. University of Durham, Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Durham. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.dur.ac.uk/sgia/ Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk University of Durbam Institute for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies *********************************** ARAFAT'S PALESTINE NATIONAL AUTHORITY *********************************** by Tariq Y. lsmael Durham Middle East Paper No. 71 June 2002 - 2 OCT 1001 Durham Middle East Papel"S lSSN 1416-4830 No.11 The Durham Middle Easl Papers series covers all aspects of the economy. politi~s, social SCll~nce. history. hterature and languages or lhe Middle East. AUlhors are invited 10 submil papers to lhe Edl!orial Board for l:onsidcration for publiealion.