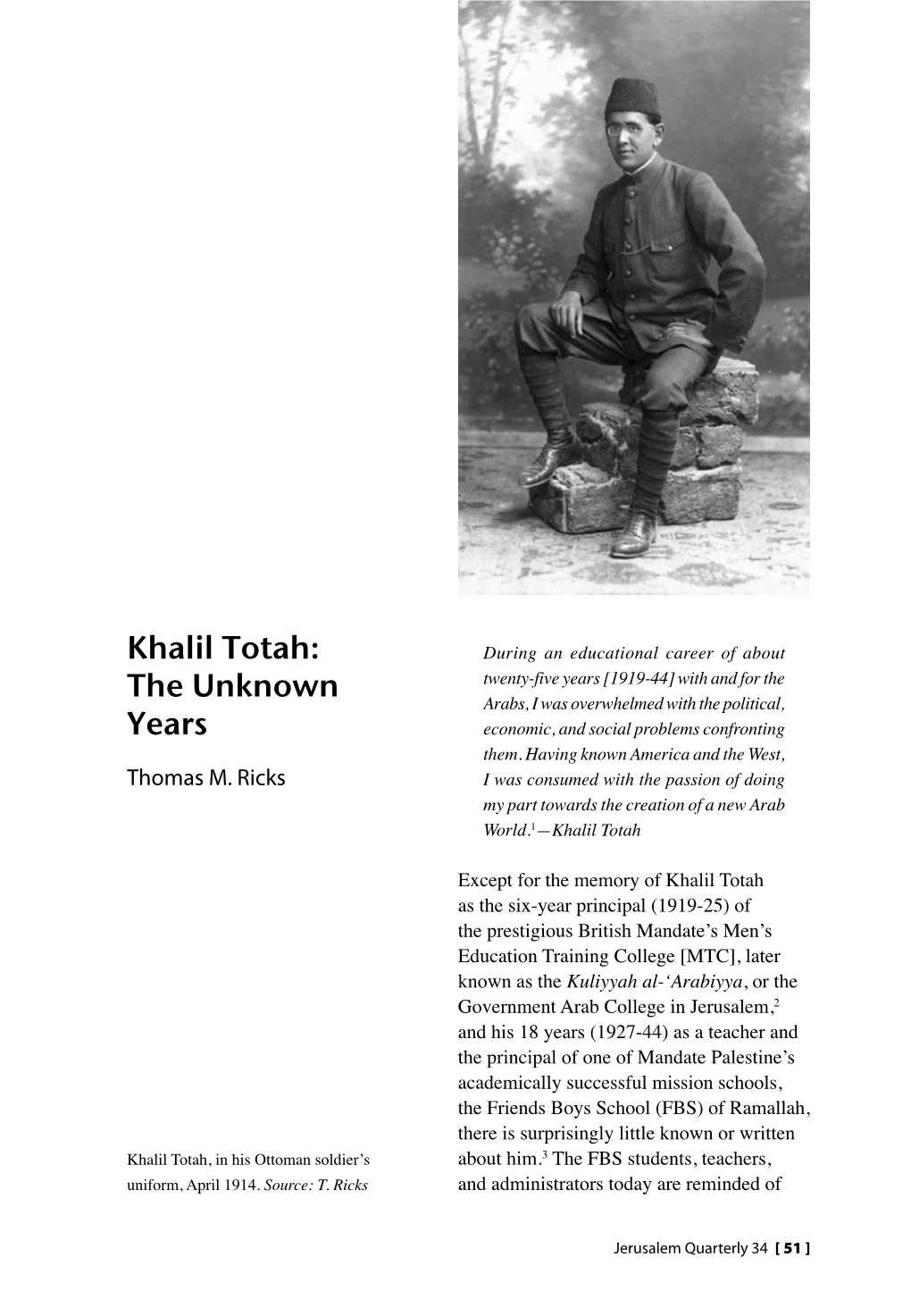

Khalil Totah: the Unknown Years Needed Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

The Israeli-Palestinian People-To-People Program

Lena C. Endresen Contact and Cooperation: The Israeli-Palestinian People-to-People Program Lena C. Endresen Contact and Cooperation: The Israeli-Palestinian People-to-People Program Fafo-paper 2001:3 1 © Fafo Institute for Applied Social Science 2001 ISSN 0804-5135 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 6 The People-to-People Program: Rationale and Assumptions .............................................................................. 8 People-to-People Program Activities ............................................................. 11 NGO Cooperative Projects ............................................................................................11 Building structures for peace .......................................................................................13 Main Challenges .............................................................................................. 16 Impact and Evaluation..................................................................................................17 The Impact of the Peace Process on People-to-People Activities...............................19 Equality as an Ambition: The Two NGO Sectors .........................................................20 Norway and the Fafo Institute for Applied Social Science as a Third Party ..............23 Conclusion ....................................................................................................... -

Using Educational Drama and Role-Playing Teaching English in Gaza

Asian Journal of Education and e-Learning (ISSN: 2321 – 2454) Volume 01– Issue 01, April 2013 Using Educational Drama and Role-Playing Teaching English in Gaza Governorates Awad Sulaiman Keshta The Islamic University of Gaza Gaza, Palestine _________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT— The purpose of the study was to examine the perceptions of the teachers' use of educational drama in teaching English in Palestine whose first language was Arabic toward English drama. To achieve the purpose of the study, the researcher used a questionnaire in order to collect data about the teachers' use of educational drama in their classes. The sample of the study was 107 female and male teachers from Gaza southern Governorates. The study findings were as follows: 1. There are statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in English language teachers' perception of the use of educational drama and role-playing in teaching English attributed to the gender. 2. There are statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in English language teachers' perception of the use of educational drama and role-playing in teaching English due to teachers' experience. 3. There are statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in English language teachers' perception of the use of educational drama and role-playing in teaching English attributed to the institution to which they belong. 4. There are statistically significant differences at (α ≤ 0.05) in English language teachers' perception of the use of educational drama and role-playing in teaching English attributed to qualifications. Based on the study results, the researcher recommends that teachers should make good use of educational drama in their classes as it is considered an essential strategy for teaching English. -

The Effectiveness of Using Drama Techniques in Teaching Difficult

JRCIET Vol. 5 , No. 3 July 2019 The Effectiveness of Using Drama Techniques in Teaching Difficult Units of EFL Course on Developing Language Proficiency and on Decreasing Anxiety Level of Intermediate Stage Students Abdullah Khader Mohammad Al Zahrani Curricula and Methods of Teaching English Faculty of Education Taif University Marwan Rasheed Arafat , Ph.D Assistant Professor of Curricula and Methods of Teaching English -Faculty of Education Taif University Abstract he current study aimed at investigating the effectiveness of using drama techniques in teaching T the difficult units of EFL course on developing language proficiency and on decreasing the anxiety level of intermediate stage students. The study adopted a quasi- experimental design (experimental / control). Also it included one independent variable which was the using drama techniques and two dependent variables which were developing language proficiency and decreasing the anxiety level. The sample of the study consisted of (N = 48) from the first intermediate grade students. The experimental group consisted of (N= 23) which was taught the difficult units through drama techniques. The control group consisted of (N= 25) which was taught the difficult units through the normal methods. The following instruments were used to achieve the questions of the study: A questionnaire to determine the difficult units based on the opinions of English supervisors and teachers. An achievement test in language proficiency. A diagnostic test to measure the level of anxiety among students. The t-test is used to determine the statistical differences between the mean scores of two groups. The current study indicated the positive effectiveness of using drama techniques on developing language proficiency and on decreasing the anxiety level for the 1st intermediate grade students. -

Studies in Comparative Education

7 Edited by Daniel S. HalpPr-in for- the Geneva Foundation z INTERNATIONAL BUREAU OF EDUCATION STUDIESINCOMPARATIVEEDUCATION To LIVE TOGETHER: SHAPINGNEWATTITUDES To PEACE THROUGHEDUCATION Edited by Daniel S. Halpe’rin Based on the Israeli-Palestinian Workshop held 26 January to 2 February 1997 at the Centre des Pens&es, Fondation Marcel Merieux, Veyrier du Lac (Annecy), France Published under the auspices of the Geneva Foundation to Protect Health in War and the Multi-faculty Programme for Humanitarian Action at Geneva University with the support of the Marcel Merieux Foundation and the International Bureau of Education The ideas and opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not neces- sarily represent the views of UNESCO:IBE. The designations employed and the presen- tation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO:IBE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ISBN: 92-3-185003-2 Printed in France by SADAG, Bellegarde. 0 UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1997 Preface Ever since its creation, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization has been strongly committed to the development of a culture of peace. As is stressed in the present UNESCO Medium-term strat- egy, the Organization is now striving to promote the idea of ‘a culture of peace’ which was formulated for the first time at the International Congress on Peace in the Minds of Men at Yamoussoukro in 1989 and subsequently elaborated on and refined, particularly at the forty-fourth session of the International Conference on Education (1994). -

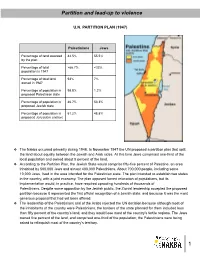

Partition and Lead-Up to Violence

P artition and leadup to violence U.N. PARTITION PLAN (1947) Palestinians Jews Percentage of land awarded 44.5% 55.5% by the plan Percentage of total >66.7% <33% population in 1947 Percentage of total land 93% 7% owned in 1947 Percentage of population in 98.8% 1.2% proposed Palestinian state Percentage of population in 46.7% 53.3% proposed Jewish state Percentage of population in 51.2% 48.8% proposed Jerusalem enclave ❖ The Nakba occurred primarily during 1948. In November 1947 the UN proposed a partition plan that split the land about equally between the Jewish and Arab sides. At this time Jews comprised onethird of the local population and owned about 5 percent of the land. ❖ According to the Partition Plan, the Jewish State would comprise fiftyfive percent of Palestine, an area inhabited by 500,000 Jews and almost 400,000 Palestinians. About 700,000 people, including some 10,000 Jews, lived in the area intended for the Palestinian state. The plan intended to establish two states in the country, with a joint economy. The plan opposed forced relocation of populations, but its implementation would, in practice, have required uprooting hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Despite some opposition by the Jewish public, the Zionist leadership accepted the proposed partition because it represented the first official recognition of a Jewish state, and because it was the most generous proposal that had yet been offered. ❖ The leadership of the Palestinians and of the Arabs rejected the UN decision because although most of the inhabitants of the country were Palestinians, the borders of the state planned for them included less than fifty percent of the country’s land, and they would lose most of the country’s fertile regions. -

Diyar Board of Directors

DiyarConsortium DiyarConsortium DiyarProductions Content Diyar Board of Directors Foreword 2 Bishop Dr. Munib Younan (Chair) Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture 6 Dr. Ghada Asfour-Najjar (Vice Chair) International Conferences 16 Mr. Jalal Odeh (Treasurer) The Model Adult Education Center 20 Dr. Versen Aghabekian (Secretary) Religion & State III 22 Mr. Albert Aghazarian The Civic Engagement Program 26 Mr. Ghassan Kasabreh Ajyal Elderly Care Program 30 Azwaj Program 32 Mr. Zahi Khouri Celebrate Recovery Project 34 Mr. Issa Kassis Diyar Academy for Children and Youth 35 Dr. Bernard Sabella Culture Program 41 Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb (Founder & Authentic Tourism Program 44 President, ex officio) Gift Shop Sales for 2015 46 Diyar Publisher 48 Media Coverage 50 Construction Projects 53 1 In all of the construction projects, Diyar emphasized alternative itineraries into their schedules. When we aesthetics, cultural heritage, and green buildings. started in 1995, there were only 60 Palestinian tour FOREWORD Thanks to utilizing solar energy, Diyar was able in 2015 guides (out of a total of 4000 guides); all of them were to generate 40% of its energy consumption through over 60 years old and had received their license from solar. By 2020, we hope to reach zero-energy goal. the Jordanian government prior to 1967. Thanks to Dar Dear Friends, al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture, today In all these years Diyar programs were highlighted in there are over 500 trained and accredited Palestinian ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUALREPORT Salaam from Bethlehem. The year 2015 marked Diyar’s 20th anniversary. It was on many media outlets including the BBC, CNN, ABC, tour guides, who became Palestine’s ambassadors, September 28, 1995 that we inaugurated Dar Annadwa in the newly renovated CBS, HBO, ARD, ZDF, ORF, BR, al-Jazeera, Ma’an News sharing the Palestinian narrative with international crypt of Christmas Lutheran Church, as a place for worldwide encounter. -

Annual Report

BETHLEHEM DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION BDF A Non - Profit Organization ANNUAL REPORT 20181 | BDF Index Board of Trustees Message 5 In Retrospect 2013-2017 6 About BDF 12 Impact of BDF Completed Projects 16 5x5 Playground Doha 16 Al-Salam Children Park-Beit Jala 18 Manger Square Project-Bethlehem 20 Said Khoury Sports Complex-Beit Sahour 22 Bethlehem Solid Waste Management 26 Launching of AFBDF 30 Information 34 Board of Trustees Message Dear Patrons, Trustees, Directors and friends, “The Bethlehem Development Foundation aims to restore I am very pleased to address you our patrons, partners and friends in some peace, love and joy to the people of Bethlehem and the this fifth periodical report. surrounding towns” -BDF Chair Samer Khoury In 2018 BDF concluded its fifth year of operations with a remarkable portfolio of ten vital projects with several others underway. BDF remains dedicated to achieving the foundation’s core vision of regenerating the Bethlehem Governorate Area through the support of our stakeholders from local governance units, religious leadership and Samer S. Khoury Chairman, BoT the region’s vibrant private sector. In this report we highlight the positive impact of BDF-supported projects on the local community: the Restoration of the Church of Nativity, the Manger Square Rehabilitation and Beautification, the Christmas Decorations and Festivities in Manger Square, the Said Khoury Sports Complex and Mini Soccer Playground in Beit Sahour, the Doha Mini Soccer Playground, the Salam Children Park in Beit Jala, the Bethlehem Governorate Solid Waste Management Project, the Rehabilitation of Sanitary Units at the Mosque of Omar in Manger Square and finally the Urban Planning Training of Municipal Engineers. -

Tawfiq Canaan an Introduction by Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb Autobiographies

Tawfiq Canaan An Introduction by Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb Autobiographies give a unique, eyewitness account of historical events experienced by one particular person, an account of a life with all its ups and downs, struggles and failures, successes and setbacks. They invite us to look at history not from a distant bird’s eye view, but through the eyes of one person in their own personal reality. However, autobiographies are not written at the time of the actual events and they constitute a rear-view mirror through a time lapse. Tawfiq Canaan started to write his autobiography in English in a pharmaceutical diary dated 1956, just a few months after his retirement in May 1955. Although still in good health, he must have had the feeling that time was slowly running out, that life was slowly but surely fading away, and that he had a story to share with his family, friends, and the visitors who were always eager to hear from him about socio-economic and political events. It must have taken him only a few months to write his memoirs. By late 1956, he had switched to documenting current affairs related to the dismissal of Glubb Pasha by the newly crowned King Hussein of Jordan on March 1st 1956, and reports on the Suez-Canal crises. This last chapter of his memoirs was less biographical and was therefore excluded from this publication. The last date in the manuscript was 1957, which means that Canaan must have felt that documenting current affairs was not his goal or worthy of his time. -

The Role of Palestinian Diaspora Institutions in Mobilizing the International Community

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2004/WG.4/CRP.6 20 September 2004 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA Arab-International Forum on Rehabilitation and Development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Towards an Independent State Beirut, 11-14 October 2004 THE ROLE OF PALESTINIAN DIASPORA INSTITUTIONS IN MOBILIZING THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY By Nadia Hijab ______________________ Note: The references in this document have not been verified. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ESCWA. 04-0456 Advisory Group • Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) • Palestinian Authority • League of Arab States • United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)* • United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)* • United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) • Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) • Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator (UNSCO) • United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)* • United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)* • United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) • International Labour Organization (ILO)* • Al Aqsa Fund/Islamic Development Bank* • World Bank • United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)* • International Organization for Migration (IOM)* • Arab NGO Network for Development (ANND)* Cosponsors • Friedrich Ebert Foundation • Norwegian People’s Aid • International Development Research Centre (IDRC) • The Norwegian Representative Office to the Palestinian Authority • Qatar Red Crescent • Consolidated Contractors Company • Arabia Insurance Company • Khatib and Alami • Gezairi Transport • El-Nimer Family Foundation _______________________ * These organizations have also contributed as sponsors in financing some of the activities of the Arab International Forum on Rehabilitation and Development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Towards an Independent State. -

Among Friends 93

Among FriendsNo 93: Autumn 2003 Published by the Europe and Middle East Section of Friends World Committee for Consultation Executive Secretary: Bronwyn Harwood, 1 Cluny Terrace, Edinburgh EH10 4SW, UK. Tel: +44 (0)131 447 6569; [email protected] Dear Friends, In August I made my first visit to Palestine. I was there just over two weeks and do not come back an instant expert on “The Situation”, although like many others I return shocked and angered by the horrendous denial of human rights, the violence, the aftermath of violence, the deep sense of hopelessness. But no, what I want to concentrate on here is to share with Friends across Europe and Middle East Section firstly my impressions of Quaker life and work in Ramallah, and secondly a brief reflection, celebration even, of the work of the Spirit in the “Holy Land”. Jenny Foot of Lancaster Girls at Inash El Usra (photo by Maggie Foyer) Monthly Meeting was my travelling companion. You will find her account of our stay and our involvement reconciliation. The project is supported financially by as volunteers on page 4. I was grateful for her Philadelphia Yearly Meeting but there is still some way companionship, resilience and constant good-humour. to go and Ramallah Quakers would love to feel they I also want to give special thanks to all the Friends in have the support of more Friends from Europe. When Ramallah, and many other local people too, for the we visited we saw the gleaming new roof, a partially warmth of their welcome. restored meeting room, new walls round the garden Right in the centre of old Ramallah is the old Meeting but a way to go in restoring the annex and the outdoor House, standing in a walled garden. -

Newsletter (2016-Apr)

A Guide to What's Inside! Query: Integrity Calendar The Social Concerns Box Religious Ed. for Children Events Into the Future Committee Notes Fellowship & Hospitality Adult Religious Education Discerning Our Future Meeting Notes April 2016 Query for April: Integrity How do we seek truth by which to live? How do we know it when we find it? In what ways does my life speak of my beliefs and values? In what ways is my life out of harmony with the truth as I know it? Why? April 2016 Calendar Meeting for Worship is at 9:30 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. every First Day (except for the first First Day of each month, when Meeting for Business is held at 9:00 a.m.). 1 Fri 7:30 p.m. BYM Young Friends (High School) Conf., Richmond VA 2 Sat 9:30 a.m. BYM Peace & Social Concerns Networking Day, Sandy Sp. 2:00 p.m. Memorial Meeting to Celebrate the Life of Michael Horne 3 Sun 9:00 a.m. Meeting for Business (Child Care is Provided) 11:00 a.m. Qkr Values & Leadership: Worship & Classes 12:30 p.m. Brainstorming Our Response to Climate Change 12:30 p.m. BFM Black Lives Matter Demonstration, Arlington Road 5/6 9:00 a.m. Undoing Racism Workshop, N Street Village 8 to 10 Pendle Hill Workshop on Our Life is Love 9 Sat 10:00 a.m. Friends Wilderness Center: Poetry with Janey Harrison 1 3:00 p.m. BFM Book Group at the Bethesda Library 10 Sun 9:30 a.m.