History's Muse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Maintained Street Inventory

City Maintained Streets Inventory DATE APPROX. AVG. STREET NAME ACCEPTED BEGINNING AT ENDING AT LENGTH WIDTH ACADEMYText0: ST Text6: HENDERSONVLText8: RD BROOKSHIREText10: ST T0.13 Tex20 ACADEMYText0: ST EXT Text6: FERNText8: ST MARIETTAText10: ST T0.06 Tex17 ACTONText0: WOODS RD Text6:9/1/1994 ACTONText8: CIRCLE DEADText10: END T0.24 Tex19 ADAMSText0: HILL RD Text6: BINGHAMText8: RD LOUISANAText10: AVE T0.17 Tex18 ADAMSText0: ST Text6: BARTLETText8: ST CHOCTAWText10: ST T0.16 Tex27 ADAMSWOODText0: RD Text6: CARIBOUText8: RD ENDText10: OF PAVEMENT T0.16 Tex26 AIKENText0: ALLEY Text6: TACOMAText8: CIR WESTOVERText10: ALLEY T0.05 Tex12 ALABAMAText0: AVE Text6: HANOVERText8: ST SWANNANOAText10: AVE T0.33 Tex24 ALBEMARLEText0: PL Text6: BAIRDText8: ST ENDText10: MAINT T0.09 Tex18 ALBEMARLEText0: RD Text6: BAIRDText8: ST ORCHARDText10: RD T0.2 Tex20 ALCLAREText0: CT Text6: ENDText8: C&G ENDText10: PVMT T0.06 Tex22 ALCLAREText0: DR Text6: CHANGEText8: IN WIDTH ENDText10: C&G T0.17 Tex18 ALCLAREText0: DR Text6: SAREVAText8: AVE CHANGEText10: IN WIDTH T0.18 Tex26 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: ARDIMONText8: PK WINDSWEPTText10: DR T0.37 Tex24 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: MARTINText8: LUTHER KING WEAVERText10: ST T0.02 Tex33 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: CURVEText8: ST ARDMIONText10: PK T0.42 Tex24 ALLENText0: AVE 0Text6:/18/1988 U.S.Text8: 25 ENDText10: PAV'T T0.23 Tex19 ALLENText0: ST Text6: STATEText8: ST HAYWOODText10: RD T0.19 Tex23 ALLESARNText0: RD Text6: ELKWOODText8: AVE ENDText10: PVMT T0.11 Tex22 ALLIANCEText0: CT 4Text6:/14/2009 RIDGEFIELDText8: -

American Title a Sociation ~ ~

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION AMERICAN TITLE A SOCIATION ~ ~ VOUJME XXXVI JUNE, 1957 NUMBER 6 TITLE NEWS Official Publication of THE AMERICAN TITLE ASSOCIATION 3608 Guardian Building-Detroit 26, Michigan Volume XXXVI June, 1957 Number 6 Table of Contents Introduction-The Federal Highway Program ......... ... ................ .. .................... 2 J. E. Sheridan Highway Laws Relating to Controlled Access Roads ..... .. ....... ........... 6 Norman A. Erbe Title Companies and the Expanded Right of Way Problems ...... ............. .. 39 , Daniel W. Rosencrans Arthur A. Anderson Samuel J. Some William A . Thuma INTRODUCTION The Federal Highway Program J. E. SHERIDAN We are extremely grateful to Nor veloped its planning sufficiently to man A. Erbe, Attorney General of the show to the satisfaction of the dis State of Iowa, for permission to re trict engineer the effect of the pro print his splendid brief embracing posed construction upon adjace.nt the highway laws of various states property, the treatment of access con relating to the control in access roads. trol in the area of Federal acquisi Mr. Erbe originally presented this m tion, and that appropriate arrange narrative form before the convention ments have been made for mainte of the Iowa Title Association in May nance and supervision over the land of this year. As is readily ascertain to be acquired and held in the name able, this is the result of a compre of the United States pending transfer hensive study of various laws touch· of title and jurisdiction to the State ing on the incidents of highway regu or the proper subdivision thereof." lations. Additionally, we are privi It is suggested that our members leged to carry the panel discussion bring this quoted portion to the at of the American Right of Way Asso tention of officers of the Highway ciation Convention held in Chicago, Department and the office of its legal May 16 and 17, dealing with "Title division, plus the Office of the Attor Companies and the Expanded Right ney General within the members' ju of Way Problems". -

Boulevards and Parkways Seattle Open Space 2100 Boulevards + Parkways Diego Velasco

Boulevards and Parkways Seattle Open Space 2100 Boulevards + Parkways Diego Velasco Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn in 1890 - Jacobs, Macdonald, Rofe, The Boulevard Book, 2002 Photo Jacobs, Macdonald, Rofe, The Boulevard Book, 2002 A multiway boulevard is a “ mixed-use public way that is by its very nature complex” Alan Jacobs, 2002 A boulevard or parkway is a wide urban street with tree-lined sidewalks and often multiple lanes of both fast and slow moving traffic. Boulevards are usually pleasant and grand promenades, flanked by rich, monumental architecture and supporting a variety of street uses. They are often “monumental links between important destina- tions.” 1 More importantly, boulevards can be open space systems that serve multiple functions at once: movement of traffic, provision of green space in the city, relief of congestion in overcrowded areas, accommodation of pedestrians and bicycles, and the nurturing of vital street life and activity in the city. Boulevards date back to the 16th century, when medieval towns abandoned their fortified walls and converted them to tree-lined walkways for public recreation. Cities like Amsterdam and Strasbourg were among the first to develop obsolete ramparts into pleasure promenades. In 1670, Louis XIV abandoned the walls of Paris and replaced these with promenades that served as the parade grounds of aristocrats and the well-to-do. These were also known as cours or allees, such as the Cour de la Reine, which extended alongside the palatial gardens of the Tuileries.1 In the mid-19th to early-20th century, boulevards came to be associated with large- scale planning efforts, such as those of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann in Paris or City Beautiful movements in the United States. -

Street Names - in Alphabetical Order

Street Names - In Alphabetical Order District / MC-ID NO. Street Name Location County Area Aalto Place Sumter - Unit 692 (Villa San Antonio) 1 Sumter County Abaco Path Sumter - Unit 197 9 Sumter County Abana Path Sumter - Unit 206 9 Sumter County Abasco Court Sumter - Unit 821 (Mangrove Villas) 8 Sumter County Abbeville Loop Sumter - Unit 80 5 Sumter County Abbey Way Sumter - Unit 164 8 Sumter County Abdella Way Sumter - Unit 180 9 Sumter County Abdella Way Sumter - Unit 181 9 Sumter County Abel Place Sumter - Unit 195 10 Sumter County Aber Lane Sumter - Unit 967 (Ventura Villas) 10 Sumter County SE 84TH Abercorn Court Marion - Unit 45 4 Marion County Abercrombie Way Sumter - Unit 98 5 Sumter County Aberdeen Run Sumter - Unit 139 7 Sumter County Abernethy Place Sumter - Unit 99 5 Sumter County Abner Street Sumter - Unit 130 6 Sumter County Abney Avenue VOF - Unit 8 12 Sumter County Abordale Lane Sumter - Unit 158 8 Sumter County Acorn Court Sumter - Unit 146 7 Sumter County Acosta Court Sumter - Unit 601 (Villa De Leon) 2 Sumter County Adair Lane Sumter - Unit 818 (Jacaranda Villas) 8 Sumter County Adams Lane Sumter - Unit 105 6 Sumter County Adamsville Avenue VOF - Unit 13 12 Sumter County Addison Avenue Sumter - Unit 37 3 Sumter County Adeline Way Sumter - Unit 713 (Hillcrest Villas) 7 Sumter County Adelphi Avenue Sumter - Unit 151 8 Sumter County Adler Court Sumter - Unit 134 7 Sumter County Adriana Way Sumter - Unit 711 (Adriana Villas) 7 Sumter County Adrienne Way Sumter - Unit 176 9 Sumter County Adrienne Way Sumter - Unit 949 (Megan -

Yeager Road Roundabout Safety Benefits Signs Specific to Double-Lane Roundabouts

YEAGER ROAD AND NORTHWESTERN AVENUE ROUNDABOUT Approximate Opening Date: Early to Mid August HOW TO DRIVE THE YEAGER ROAD AND NORTHWESTERN AVENUE ROUNDABOUT » As you approach the roundabout, slow your vehicle to the posted advisory speed. » Use lane choice signs and arrows on the pavement to choose the appropriate lane before entering the roundabout. » Yield to any pedestrians in crosswalks » Yield to traffic circulating in the roundabout. Do not stop unless it is necessary. » Once inside the roundabout, circulate counterclockwise around the central island to your desired exit. Do not change lanes within the roundabout. N N N NORTHWESTERN AVENUE NORTHWESTERN AVENUE NORTHWESTERN AVENUE YEAGER ROAD YEAGER ROAD YEAGER ROAD ROUNDABOUT SAFETY BENEFITS SIGNS SPECIFIC TO DOUBLE-LANE ROUNDABOUTS » Reduction of traffic speeds (15 to 25 mph) » Drastic reductions in crash rates when compared to a traditional intersection: - Up to 90% reduction in fatalities - 76% reduction in crashes resulting in injury - 30 to 40% reduction in crashes involving pedestrians » Reduction in conflict points (point at which two opposing vehicle paths cross, and thus a potential for a collision exists) YEAGER RD 15 MPH Roundabout Ahead: This sign is posted in advance of the roundabout to alert drivers that they are approaching a roundabout. Underneath the roundabout ahead sign, as shown here, two optional signs may be used. One is the cross-street sign, which tells the motorist the name of the intersecting street in advance of the intersection. The other is an advisory speed. Conflict Point Comparison OTHER BENEFITS OF ROUNDABOUTS » Efficiency: Because traffic flow is smooth at a roundabout, the total Chevron (black arrows on white background) and One- number of vehicles that must stop is drastically . -

Parkway Rules and Regulations

Denver Parks and Recreation Policies and Procedures Policy name: Parkways Building Line Restrictions Number: Policy name: PARKWAYS BUILDING LINE Effective: RESTRICTIONS Supersedes: December, 1981 Application: Number: Approved by Deputy Manager or Division Head: Approved by Manager: Other a rovals: Contents. Policy 1.0 Purpose 2.0 Authority 3.0 Definitions 4.0 Established Setbacks for Designated Parkways 5.0 Architectural Features 6.0 Compliance Review and Submittal Requirements 7.0 Existing and Exceptional Circumstances 8.0 Appeals POLICY. It is the policy of Denver Parks and Recreation that structures located on private property a~ong Denver designated parkways comply with building line restrictions, or setbacks, in accordance with and subject to the standards, requirements, and procedures of this Policy. 1.0 PURPOSE. This Policy is adopted to amend and restate the Rules and Regulations Governing Building Line Restrictions Around Parkways, as amended in December, 1981. This Policy is both an expression of the policy of the Department of Parks and Recreation with respect to administration and application of the established setbacks along designated parkways as well as an embodiment of the rules and regulations for the implementation and enforcement of the established setbacks along designated parkways of the City and County of Denver. 2.0 AUTHORITY. Under section 2.4.4(B) of the City Charter, the Department of Parks and Recreation has the duty and power "[t]o establish a building line or lines, determining the distance at which all structures may be erected upon any private premises fronting any park or parkway and, in the name of the City and County, to prevent the erection and require the removal of all structures outside said lines. -

US 41 at GULFSTREAM AVENUE ROUNDABOUT Financial Project ID: 438137-1-62-01

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION US 41 AT GULFSTREAM AVENUE ROUNDABOUT Financial Project ID: 438137-1-62-01 Virtual Public Meeting Summary of Comments Received The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) District One conducted a virtual public meeting on Wednesday, December 16, 2020, regarding the US 41 at Gulfstream Avenue Roundabout Construction Project in Sarasota, Florida. The meeting began with a brief presentation, followed by questions and comments from the public. A total of 189 questions and comments were received during the meeting, by email, via the project website, and by postal mail. Comments have been entered into the summary exactly as they were submitted by user. Duplicate questions/comments from the same user have been excluded. A recording of the virtual public meeting and questions and responses, can be found on the project website at the links referenced below: Virtual Public Meeting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVNmAf4zNfA&feature=youtu.be Questions/Responses: http://www.swflroads.com/gulfstreamroundabout/US‐41‐Gulfstream‐RAB‐VPM‐Questions‐Responses.pdf More information about the project can be found on the project webpage. http://www.swflroads.com/gulfstreamroundabout/index.html 1 Virtual Public Meeting, December 16, 2020 Summary of Comments Received FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION US 41 AT GULFSTREAM AVENUE ROUNDABOUT FINANCIAL PROJECT ID# 438137-1-62-01 1. Colette R Question/Comment: “"Hi Alice, Thank you for providing an in‐depth and informative meeting regarding the US 41 at Gulfstream RAB. Please send a transcript so that I may place in my file. I would also like to be added to any updates on this matter." Response: Thank you Colette. -

University Avenue Complete Streets Corridor Revitalization Project

University Avenue Complete Streets Corridor Revitalization Project The University of Arkansas at Little Rock Table of Contents A. Project Description . 1 Users . 1 Transportation Challenges . 2 Proposed Statement of Work. .. 3 History of the Project . 4 University District . 5 University District Partnership . 6 University District Neighborhood Association . .. 7 University District Development Corporation . 7 UALR Participation . 7 Coordination with Other Planning Efforts . 7 Four Corners Redevelopment Plan. 8 University Village - studioMAIN . 8 STIP. .. 8 Campus Planning Team. .9 Ladders of Opportunity. 9 B. Project Location . 9 C. Project Parties . .10 D. Grant Funds and Sources and Uses of Project Funds . 12 E. Selection Criteria . 13 i. Primary Selection Criteria a. State of Good Repair . 14 b. Economic Competitiveness . 14 c. Quality of Life . 17 Walkability . 18 Access . .. 19 i Health Benefits of Walkability . 20 Other Benefits of Walkability . 20 Improved Transportation Choices . 21 d. Environmental Sustainability . 22 e. Safety . 22 Pedestrian / Bicycle Safety . 22 Vehicular Safety . .25 Transit Safety . 25 ii. Secondary Selection Criteria a. Partnership . .. .. 26 b. Innovation . .. .27 F. Results of Benefit Cost Analysis . 27 G. Project Readiness . 28 Technical Feasibility . .. 28 Financial Feasibility . 28 Project Schedule. 29 Required Approvals . .. 29 Assessment of Project Risks and Mitigation Strategies. .. 30 H. Federal Wage Rate Certification . 30 I. Appendices . 30 Appendix A University District by Census Tracts Appendix B Detailed Project Costs Appendix C Map of Other Redevelopment Efforts Near University District Appendix D Map of Project Area Appendix E Metroplan Board Resolution 15-02 Appendix F University District Partners Appendix G Technical Details of the Benefit-Cost Analysis Appendix G-1 Notes to Benefit-Cost Analysis ii List of Figures Figure 1 University District . -

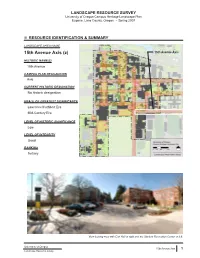

15Th Avenue Axis (Z) 15Th Avenue Axis

LANDSCAPE RESOURCE SURVEY University of Oregon Campus Heritage Landscape Plan Eugene, Lane County, Oregon • Spring 2007 n RESOURCE IDENTIFICATION & SUMMARY LANDSCAPE AREA NAME 5th Avenue Axis (z) 5th Avenue Axis HISTORIC NAME(S) 15th Avenue CAMPUS PLAN DESIGNATION Axis CURRENT HISTORIC DESIGNATION No historic designation ERA(S) OF GREATEST SIGNIFICANCE Lawrence/Cuthbert Era Mid-Century Era LEVEL OF HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE Low LEVEL OF INTEGRITY Good RANKING Tertiary View looking west with Earl Hall at right and the Student Recreation Center at left. University of Oregon 15th Avenue Axis Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey 5TH AVENUE AXIS LANDSCAPE AREA SITE MAP — Highlighting existing elements from the period of significance (1876-1974). Some of the Douglas firs planted Crimson King Norway Retaining wall appeared during near the Onyx Intersection may maples were planted during the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era date back to the Inception Era the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era Straub Hall Green Earl Complex Living Learning Walton Complex Straub Hall Center 5th Avenue Student Agate Street University Street Recreation Hayward Field Center * note: Period of Significance refers to the project period of 1876-1974 University of Oregon 15th Avenue Axis Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey 5TH AVENUE AXIS SUMMARY OF EXISTING HISTORIC FEATURES Most of the historic features associated with the Inception Era, and the large retaining wall of the 15th Avenue Axis are street trees. The row of SRC field and the Crimson King Norway maples Douglas firs between Straub Hall and University are from the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era. The street Street, and the row of Norway maples in front of has been associated with Hayward Field since the the Student Recreation Center’s (SRC) outdoor 1920s, though the north end of that facility was playing field are all from the eras of significance. -

Review of the a and C Lines

Review of the A and C Lines ,. December 11, 2015 Page intentionally left blank AC Line Review Executive Summary Executive Summary The attached report provides a comprehensive review of operations on the A and C lines. Combined, the two lines serve 800,000 riders a day across three boroughs and connect to many of the most important intermodal hubs in New York City. The A differs from most other New York City Transit subway lines in that its route splits three ways at its southern end in eastern Queens. It is also exceptionally long, at 32 miles between 207 St and Far Rockaway-Mott Av. Like many other subway lines, it merges several times with other lines. The combination of these traits tends to reduce reliability. In contrast, the C is a shorter line scheduled to run less frequently than the A and many other lines. C service is relatively reliable, even though it has historically been assigned some of the oldest cars in the system. This review has been prepared within the context of NYC Transit’s service planning procedures, and all discussions of service levels take into account established guidelines for designing and scheduling service. NYC Transit determines how many trains run on a given line based on a number of factors, including line capacity, equipment availability, and the Rapid Transit Loading Guidelines. The Guidelines ensure that limited resources are equitably allocated throughout the system by establishing, by time of day, maximum passenger load levels and minimum service frequencies, where operationally feasible. The Guidelines are applied by evaluating average ridership levels at locations where trains are most heavily loaded (“peak load points”) to develop recommended service frequencies, where operationally feasible. -

Leucadia Blvd/ Hygeia Avenue Roundabout

Leucadia Blvd/ Hygeia Avenue Roundabout PROJECT STATUS ABOUT THE PROJECT Project design is complete. This project will construct a roundabout at Leucadia Currently finishing easement Boulevard and Hygeia Avenue in Leucadia. This new acquisition and finalizing utility roundabout will complete the original three roundabouts relocation design. contemplated for the Leucadia Boulevard corridor between Orpheus Avenue and Vulcan Avenue. The intersection will be regraded to provide a flatter road profile at the roundabout. The project includes landscape enhancements and sidewalk improvements as well. 505 South Vulcan Avenue Encinitas, CA 92024 760.633.2600 | encinitasca.gov BENEFITS • Improved safety for vehicles and cyclists by eliminating left turns and reducing conflict points. • Better pedestrian mobility through the corridor by adding new sidewalk. • Improved traffic flow through the corridor by removing the stop sign at Leucadia Boulevard and Hygeia Avenue. • Enhanced aesthetics through new UPCOMING MILESTONES landscaping, trees and improved street lighting. Project design is complete, right of way acquisition is at 75% completion and utility relocations are being initiated. • Reduced greenhouse gases by eliminating required stopping. • Spring 2021: Complete right of way phase • Summer 2021: Seek construction funding • Fall 2021: Utility relocation complete PROJECT BUDGET • Fall 2021: Ready to start construction, if funded The current budget for this project is $3,118,000 and includes project planning, design, environmental analysis and partial construction funding. Additional funding is * All dates are approximate and subject to change. Last needed to fully fund construction. Updated February 3, 2021. CONTACT US For questions or concerns about the project, please contact Matt Widelski, Senior Engineer at: [email protected] or 760-633-2862 505 South Vulcan Avenue Encinitas, CA 92024 760.633.2600 | encinitasca.gov . -

Public Understanding of State Hwy Access Management Issues

PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF STATE HIGHWAY ACCESS MANAGEMENT ISSUES Prepared by: Market Research Unit - M.S. 150 Minnesota Department of Transportation 395 John Ireland Boulevard St. Paul, MN 55155 Prepared for: Office of Access Management - M.S. 125 Minnesota Department of Transportation 555 Park Street St. Paul, MN 55103 Prepared with Cook Research & Consulting, Inc. assistance from: Minneapolis, MN Project M-344 JUNE 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I. INTRODUCTION A. Background ............................................... 1 B. Study Objectives ........................................... 2 C. Methodology .............................................. 4 II. DETAILED FINDINGS ......................................... 7 A. Duluth -- U S Highway 53/State Highway 194 ..................... 7 1. Description of Study Area .................................. 7 2. General Attitudes/Behavior ................................ 7 a. Respondents' Use of Roadway ........................... 8 b. Roadway Purpose ..................................... 8 c. Traffic Flow vs. Access to Businesses ..................... 9 3. Perceived Changes in Study Area .......................... 10 a. Changes to Roadway ................................. 10 b. Changes in Land Use ................................. 11 c. Land Use/Roadway Relationship ........................ 11 4. Roadway Usefulness .................................... 11 a. How Well Does the Road Work? ........................ 11 b. Have You Changed How You Drive the Road? ............. 12 c. Safety/Risks of