American Title a Sociation ~ ~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic

MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration for Streets and Highways Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic Dotted line indicates edge of binder spine. MM UU TT CC DD U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration 2003 Edition Page i The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is approved by the Federal Highway Administrator as the National Standard in accordance with Title 23 U.S. Code, Sections 109(d), 114(a), 217, 315, and 402(a), 23 CFR 655, and 49 CFR 1.48(b)(8), 1.48(b)(33), and 1.48(c)(2). Addresses for Publications Referenced in the MUTCD American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) 444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 249 Washington, DC 20001 www.transportation.org American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) 8201 Corporate Drive, Suite 1125 Landover, MD 20785-2230 www.arema.org Federal Highway Administration Report Center Facsimile number: 301.577.1421 [email protected] Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) 120 Wall Street, Floor 17 New York, NY 10005 www.iesna.org Institute of Makers of Explosives 1120 19th Street, NW, Suite 310 Washington, DC 20036-3605 www.ime.org Institute of Transportation Engineers -

Petition for Writ of Certiorari of Fred J. Eychaner

No. In the Supreme Court of the United States FRED J. EYCHANER, PETITIONER v. CITY OF CHICAGO, RESPONDENT ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE APPELLATE COURT OF ILLINOIS PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI THOMAS GESELBRACHT KOSTA STOJILKOVIC DLA PIPER LLP Counsel of Record 444 West Lake Street, KIERAN GOSTIN Suite 900 XIAO WANG Chicago, IL 60606 MEGHAN CLEARY (312) 368-4094 WILKINSON STEKLOFF LLP thomas.geselbracht@ 2001 M St, N.W., 10th Floor dlapiper.com Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 847-4000 kstojilkovic@ wikinsonstekloff.com Counsel for Petitioner i QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW 1. Is the possibility of future blight a permissible ba- sis for a government to take property in an unblighted area and give it to a private party for private use? 2. Should the Court reconsider its decision in Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005)? ii LIST OF ALL PARTIES The parties to the proceeding are Petitioner Fred J. Eychaner—the owner of the property in question—and Respondent City of Chicago. The proceedings that are directly related to the case are as follows: • City of Chicago v. Fred J. Eychaner & Un- known Owners, No. 1-19-1053, Appellate Court of Illinois. Opinion filed May 11, 2020. • City of Chicago v. Fred J. Eychaner & Un- known Owners, No. 1-13-1833, Appellate Court of Illinois. Opinion filed January 21, 2015. • City of Chicago v. Fred. J. Eychaner & Un- known Owners, No. 05-L-050792, Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois. Judgment entered February 11, 2013, and December 26, 2018. -

Roundabout Planning, Design, and Operations Manual

Roundabout Planning, Design, and Operations Manual December 2015 Alabama Department of Transportation ROUNDABOUT PLANNING, DESIGN, AND OPERATIONS MANUAL December 2015 Prepared by: The University Transportation Center for of Alabama Steven L. Jones, Ph.D. Abdulai Abdul Majeed Steering Committee Tim Barnett, P.E., ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Stuart Manson, P.E., ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Sonya Baker, ALDOT Office of Safety Operations Stacey Glass, P.E., ALDOT Maintenance Stan Biddick, ALDOT Design Bryan Fair, ALDOT Planning Steve Walker, P.E., ALDOT R.O.W. Vince Calametti, P.E., ALDOT 9th Division James Brown, P.E., ALDOT 2nd Division James Foster, P.E., Mobile County Clint Andrews, Federal Highway Administration Blair Perry, P.E., Gresham Smith & Partners Howard McCulloch, P.E., NE Roundabouts DISCLAIMER This manual provides guidelines and recommended practices for planning and designing roundabouts in the State of Alabama. This manual cannot address or anticipate all possible field conditions that will affect a roundabout design. It remains the ultimate responsibility of the design engineer to ensure that a design is appropriate for prevailing traffic and field conditions. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1. Purpose ...................................................................................................... 1-5 1.2. Scope and Organization ............................................................................... 1-7 1.3. Limitations ................................................................................................... -

The Gibraltar Highway Code

P ! CONTENTS Introduction Rules for pedestrians 3 Rules for users of powered wheelchairs and mobility scooters 10 Rules about animals 12 Rules for cyclists 13 Rules for motorcyclists 17 Rules for drivers and motorcyclists 19 General rules, techniques and advice for all drivers and riders 25 Road users requiring extra care 60 Driving in adverse weather conditions 66 Waiting and parking 70 Motorways 74 Breakdowns and incidents 79 Road works, level crossings and tramways 85 Light signals controlling traffic 92 Signals by authorised persons 93 Signals to other road users 94 Traffic signs 96 Road markings 105 Vehicle markings 109 Annexes 1. You and your bicycle 112 2. Vehicle maintenance and safety 113 3. Vehicle security 116 4. First aid on the road 116 5. Safety code for new drivers 119 1 Introduction This Highway Code applies to Gibraltar. However it also focuses on Traffic Signs and Road Situations outside Gibraltar, that as a driver you will come across most often. The most vulnerable road users are pedestrians, particularly children, older or disabled people, cyclists, motorcyclists and horse riders. It is important that all road users are aware of The Code and are considerate towards each other. This applies to pedestrians as much as to drivers and riders. Many of the rules in the Code are legal requirements, and if you disobey these rules you are committing a criminal offence. You may be fined, or be disqualified from driving. In the most serious cases you may be sent to prison. Such rules are identified by the use of the words ‘MUST/ MUST NOT’. -

City Maintained Street Inventory

City Maintained Streets Inventory DATE APPROX. AVG. STREET NAME ACCEPTED BEGINNING AT ENDING AT LENGTH WIDTH ACADEMYText0: ST Text6: HENDERSONVLText8: RD BROOKSHIREText10: ST T0.13 Tex20 ACADEMYText0: ST EXT Text6: FERNText8: ST MARIETTAText10: ST T0.06 Tex17 ACTONText0: WOODS RD Text6:9/1/1994 ACTONText8: CIRCLE DEADText10: END T0.24 Tex19 ADAMSText0: HILL RD Text6: BINGHAMText8: RD LOUISANAText10: AVE T0.17 Tex18 ADAMSText0: ST Text6: BARTLETText8: ST CHOCTAWText10: ST T0.16 Tex27 ADAMSWOODText0: RD Text6: CARIBOUText8: RD ENDText10: OF PAVEMENT T0.16 Tex26 AIKENText0: ALLEY Text6: TACOMAText8: CIR WESTOVERText10: ALLEY T0.05 Tex12 ALABAMAText0: AVE Text6: HANOVERText8: ST SWANNANOAText10: AVE T0.33 Tex24 ALBEMARLEText0: PL Text6: BAIRDText8: ST ENDText10: MAINT T0.09 Tex18 ALBEMARLEText0: RD Text6: BAIRDText8: ST ORCHARDText10: RD T0.2 Tex20 ALCLAREText0: CT Text6: ENDText8: C&G ENDText10: PVMT T0.06 Tex22 ALCLAREText0: DR Text6: CHANGEText8: IN WIDTH ENDText10: C&G T0.17 Tex18 ALCLAREText0: DR Text6: SAREVAText8: AVE CHANGEText10: IN WIDTH T0.18 Tex26 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: ARDIMONText8: PK WINDSWEPTText10: DR T0.37 Tex24 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: MARTINText8: LUTHER KING WEAVERText10: ST T0.02 Tex33 ALEXANDERText0: DR Text6: CURVEText8: ST ARDMIONText10: PK T0.42 Tex24 ALLENText0: AVE 0Text6:/18/1988 U.S.Text8: 25 ENDText10: PAV'T T0.23 Tex19 ALLENText0: ST Text6: STATEText8: ST HAYWOODText10: RD T0.19 Tex23 ALLESARNText0: RD Text6: ELKWOODText8: AVE ENDText10: PVMT T0.11 Tex22 ALLIANCEText0: CT 4Text6:/14/2009 RIDGEFIELDText8: -

ALLEY (NS) – Washington Avenue to Wright Avenue, Deane Boulevard to Quincy Avenue

ALLEY (NS) – Washington Avenue to Wright Avenue, Deane Boulevard to Quincy Avenue Alderman District 9 – Trevor Jung Existing pavement - Bituminous Right-of-way width - 16’ PCI – Alleys not rated Improvement Cost - Concrete at $74.00/ft Alderman Request Last Public Hearing Date – Never City of Racine - Assessment Schedule CITY ENGINEER'S OFFICE AUTHORITY - Benefits and Damage FOR: PORTLAND CEMENT CONCRETE PAVING RESOLUTION NUMBER 058319 15-May-20 LOCATION - Alley (NS) from Washington Ave to Wright Ave, Deane Blv Page 1 of 2 TAXNO NAME FRONTAGE RATE BENEFITS ADJUST SPEC. ADJ. ADDRESS MAILING ADDRESS ASSESSMENT 10192000 Mauer, Kristi L. 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 1367 Deane Boulevard 1367 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10193000 Arndt, Ryan 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 1365 Deane Boulevard 1365 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10194000 Kosterman, Robert P. & Margaret M. 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 1363 Deane Boulevard 1363 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10195000 Lochowitz, Justin 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 1359 Deane Boulevard 1359 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10195000 Lochowitz, Justin 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 1359 Deane Boulevard 1359 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10196000 Johnson, Kenneth Sr. 35.000$74.00 $2,590.00 $0.00 $0.00 Cloyd, Christina 1355 Deane Boulevard 1355 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,590.00 10197000 Garcia, Gregory 40.000$74.00 $2,960.00 $0.00 $0.00 1351 Deane Boulevard 1351 Deane Boulevard Racine, WI 53405 $2,960.00 10198000 Williams, Randall 40.000$74.00 $2,960.00 $0.00 $0.00 Veltus, Julie 1345 Deane Boulevard 5735 Ridgecrest Drive Racine, WI 53403 $2,960.00 10199000 Degroot, Matthew J. -

"2. Sidewalks". "Boston Complete Streets Design Guide."

Sidewalk Zone Widths The width of the sidewalk contributes to the degree of When making decisions for how to allocate sidewalk space, comfort and enjoyment of walking along a street. Narrow the following principles should be used: sidewalks do not support lively pedestrian activity, and may create dangerous conditions where people walk in the Frontage Zone street. Typically, a five foot wide Pedestrian Zone supports > The Frontage Zone should be maximized to provide space two people walking side by side or two wheel chairs passing for cafés, plazas, and greenscape elements along build- each other. An eight foot wide Pedestrian Zone allows two ing facades wherever possible, but not at the expense of pairs of people to comfortably pass each other, and a ten reducing the Pedestrian Zone beyond the recommended foot or wider Pedestrian Zone can support high volumes of minimum widths. pedestrians. Pedestrian Zone Vibrant sidewalks bustling with pedestrian activity are not > The Pedestrian Zone should be clear of any obstructions only used for transportation, but for social walking, lingering, including utilities, traffic control devices, trees, and furniture. and people watching. Sidewalks, especially along Downtown When reconstructing sidewalks and relocating utilities, all Commercial, Downtown Mixed-Use, and Neighborhood Main utility access points and obstructions should be relocated Streets, should encourage social uses of the sidewalk realm outside of the Pedestrian Zone. by providing adequate widths. > While sidewalks do not need to be perfectly straight, the SIDEWALKS Pedestrian Zone should not weave back and forth in the When determining sidewalk zone widths, factors to consider right-of-way for no other reason than to introduce curves. -

Petition For/Request to Initiate Vacation of Public Highway, Street, Alley Or Easement Requirements and Process Overview

Petition for/request to initiate vacation of public highway, street, alley or easement Requirements and process overview The City of St. Louis Park will vacate public highways, streets, alleys or easements if it is found that the city has no current or future need for these lands. Proceedings to vacate such land may be commenced by petition of a majority of the owners of property fronting upon the portion of the public highway, street, alley or easement to be vacated, by action of the St. Louis Park City Council or by recommendation of the St. Louis Park Planning Commission. In order to constitute a petition for vacation, a majority of abutting property owners of the portion of public highway or street to be vacated must appear on the petition form. If the request is for vacation of a public alley or easement, it must be signed by the majority of owners of property adjacent to the alley or easement in the block where the alley or easement is situated, whether or not the petition requests vacation of the entire alley or easement. The petition shall be filed with the city clerk. If the application represents a request to the planning commission to recommend and to the city council to initiate vacation, that must be specifically stated. The applicant is encouraged to discuss the proposal with community development staff prior to completion of final plans and filing of a petition/request. Submittal checklist ☐ Petition/request ☐ Filing fee (see application for fee schedule) ☐ A complete and accurate legal property description must be submitted if the property to be vacated is an easement. -

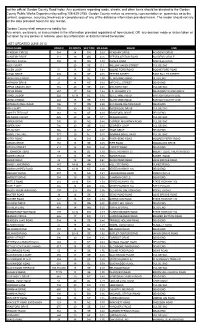

This Gordon County Online Road Index Is a Public Resource of General Information

This Gordon County Online Road Index is a public resource of general information. The Gordon County Road Index contained herein is not the official Gordon County Road Index. Any questions regarding roads, streets, and other items should be directed to the Gordon County Public Works Department by calling 706-629-2785. Gordon County makes no warranty, representation or guarantee as to the content, sequence, accuracy,timeliness or completeness of any of the database information provided herein. The reader should not rely on the data provided herein for any reason. Gordon County shall assume no liability for: Any errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in the information provided regardless of how caused; OR any decision made or action taken or not taken by any person in reliance upon any information or data furnished hereunder. LAST UPDATED JUNE 2013 ROAD NAME ROAD # RD WIDTH SECTION MILEAGE BEGIN END ACADEMY CIRCLE 584 14 SW 0.03 ACADAMY DRIVE ACADEMY DRIVE ACADEMY DRIVE 111 19 SW 0.75 REEVES STATION ROAD ACADEMY CIRCLE AIRPORT CIRCLE 592 18 NW 0.59 CLINES ROAD NORVILLE DRIVE ALEX COURT 20 SE 0.1 WILLOW HAVEN STREET CUL DE SAC ALLEN LOOP 54 18 SE 0.68 BOONE FORD ROAD BOONE FORD ROAD ALTON DRIVE 599 18 SE 0.15 PETERS STREET EAST FULLER STREET AMAKANATA ROAD 41 18 SE 1.00 DEWS POND ROAD DEAD END ANTHONY DRIVE 21 18 NE 0.12 MITCHELL STREET DEAD END APPLE GROVE LANE 716 20 SE 0.04 ORCHARD WAY CUL DE SAC APPLE ROAD 257 17 NE 1.42 U.S. -

Boulevards and Parkways Seattle Open Space 2100 Boulevards + Parkways Diego Velasco

Boulevards and Parkways Seattle Open Space 2100 Boulevards + Parkways Diego Velasco Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn in 1890 - Jacobs, Macdonald, Rofe, The Boulevard Book, 2002 Photo Jacobs, Macdonald, Rofe, The Boulevard Book, 2002 A multiway boulevard is a “ mixed-use public way that is by its very nature complex” Alan Jacobs, 2002 A boulevard or parkway is a wide urban street with tree-lined sidewalks and often multiple lanes of both fast and slow moving traffic. Boulevards are usually pleasant and grand promenades, flanked by rich, monumental architecture and supporting a variety of street uses. They are often “monumental links between important destina- tions.” 1 More importantly, boulevards can be open space systems that serve multiple functions at once: movement of traffic, provision of green space in the city, relief of congestion in overcrowded areas, accommodation of pedestrians and bicycles, and the nurturing of vital street life and activity in the city. Boulevards date back to the 16th century, when medieval towns abandoned their fortified walls and converted them to tree-lined walkways for public recreation. Cities like Amsterdam and Strasbourg were among the first to develop obsolete ramparts into pleasure promenades. In 1670, Louis XIV abandoned the walls of Paris and replaced these with promenades that served as the parade grounds of aristocrats and the well-to-do. These were also known as cours or allees, such as the Cour de la Reine, which extended alongside the palatial gardens of the Tuileries.1 In the mid-19th to early-20th century, boulevards came to be associated with large- scale planning efforts, such as those of Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann in Paris or City Beautiful movements in the United States. -

95 Express Phase 3A-1 FPN #S: 433108-4-52-01 & 428009-1-52-01

95 Express Phase 3A-1 FPN #s: 433108-4-52-01 & 428009-1-52-01 95 Express Phase 3A-1 will extend the existing express lanes north from just south of Broward Boulevard to just north of Commercial Boulevard in Broward County. One lane will be added and the High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lane will be Contact Us… converted to create two express lanes in each direction. This project includes ramp signalization from Hallandale Beach Boulevard to Commercial Boulevard. Other Email: work includes: installing Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) and tolling [email protected] equipment; widening bridges; and installing noise barrier walls at locations along I- 95 Southbound between Broward Boulevard and NW 6th Street, and along I-95 Northbound between Powerline Road and Commercial Boulevard. Contract time Call: for this $149 million project began Monday, October 4, 2015, with design activities currently underway. Construction began August 21, 2016, and is expected to be Construction PIO completed Spring 2020. Please note that this schedule is subject to change due to Office: weather or other unforeseen circumstances. (954) 299-6561 As of Winter 2016, project activities are as follows: • Or Design, survey and maintenance activities • Broward Boulevard ramp widening and reconstruction • Broward Boulevard widening and paving For information about • I-95 northbound milling and resurfacing 95 Express including lane closure Lane Closures & Traffic Impacts: information visit: Lane closures are occuring in the work zone from 10:30 p.m. to 5:30 a.m. Sunday through Thursday. Entrance and exit ramps will be closed as needed. 95Express.com Upcoming Project Milestones (weather permitting): • Winter 2016/2017: Ongoing milling and resurfacing of I-95 northbound from Broward Boulevard to Oakland Park Boulevard • Winter 2016/2017: Broward Boulevard construction anticipated to be completed • Early 2017: Sound wall work will begin For around-the-clock, real time, I-95 traffic information, call 511. -

Chapter 9- the Circulation Plan (PDF)

CHAPTER 9- THE CIRCULATION PLAN The Circulation Plan in Middletown is coordinated with the State's system of expressways, including Interstate Route 91 about to be completed, Route 9 in the Connecticut valley and the future Route 6A across the State. Middletown needs a thoroughfare between Route I-91 near Country Club Road and the center. The Circulation Plan is also coordinated with the development of downtown Middletown, already described, including the circumferential "ring road" around the center. Regional Expressways The plan which the State Highway Department has made for a state-wide expressway system includes three such routes which traverse Middletown. Interstate Route 91 is under construction from New Haven northward and crosses the western part of the City. Meeting the Connecticut Turnpike at New Haven, this will be the principal approach to Middletown from the southwest, including metropolitan New York. This is scheduled to be completed by the end of 1965. Route 9 is the principal north-south artery of the Connecticut Valley. It passes through Middletown center as an at-grade boulevard along the riverfront mixing local and through traffic. South of the center, it has been improved as a four-lane expressway to a point near the Haddam town line. Its rebuilding as an expressway to the Connecticut Turnpike at Old Saybrook will be undertaken shortly. North of Middletown Route 9 will soon be relocated and rebuilt as an expressway, turning westerly from its present line to join I-91 in the western part of Cromwell. Thus traffic to Middletown from Hartford and the north will start on I-91 and transfer to the new Route 9 a few miles north of the City.