Since Around 2012, the Use of Trigger Warnings Or Content Warnings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought TIMES to BE CONFIRMED

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought TIMES TO BE CONFIRMED: provisionally, Tuesday 1:30-2:45, Thursday TBC Fall Semester 2020 Professor Katrina Forrester Office Hours: TBC E-mail: [email protected] Teaching Fellows: Celia Eckert, Soren Dudley, Kierstan Carter, Eve O’Connor Course Description: What is feminism? What is patriarchy? What and who is a woman? How does gender relate to sexuality, and to class and race? Should housework be waged, should sex be for sale, and should feminists trust the state? This course is an introduction to feminist political thought since the mid-twentieth century. It introduces students to classic texts of late twentieth-century feminism, explores the key arguments that have preoccupied radical, socialist, liberal, Black, postcolonial and queer feminists, examines how these arguments have changed over time, and asks how debates about equality, work, and identity matter today. We will proceed chronologically, reading texts mostly written during feminism’s so-called ‘second wave’, by a range of influential thinkers including Simone de Beauvoir, Shulamith Firestone, bell hooks and Catharine MacKinnon. We will examine how feminists theorized patriarchy, capitalism, labor, property and the state; the relationship of claims of sex, gender, race, and class; the development of contemporary ideas about sexuality, identity, and gender; and how and whether these ideas change how fundamental problems in political theory are understood. 1 Course Requirements: Undergraduate students: 1. Participation (25%): a. Class Participation (15%) Class Participation is an essential part of making a section work. Participation means more than just attendance. You are expected to come to each class ready to discuss the assigned material. -

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Carol Hanisch, June 1, 2006

Reflections on the 1960s Women's Liberation Movement as "racist," post by Carol Hanisch, June 1, 2006 An exerpt from: Carol Hanisch, “The Personal is Political”, Attacking Women, Carnival of Feminists 17, and What the Heck Posted by Heart ⋅ June 22, 2006 ⋅ 22 Comments http://womensspace.wordpress.com/ I came across a really interesting and recent feminist forum on the subject of the political being personal entitled, Hanisch Forum on the Personal is Political held from May 26 through June 11, 2006, and described as follows: From May 26 through June 11, 2006, "The 'Second Wave' and Beyond" hosted a special forum among scholars and activists led by Carol Hanish and inspired by her article "The Personal is Political" and the new introduction published below. Please read the discussion in the archives (with comments by Carol Hanisch, Judith Ezekiel, Chude [Pam] Allen, Ariel Dougherty, [Margaret] Rivka Polatnick, Kimberly Springer, Stephanie Gilmore, and Cathy Cade). Here is an example of one of Hanisch's comments in the forum, dated June 1, 2006 (note: "WL" and "WLM" are acronyms for "Women's Liberation" and "Women's Liberation Movement"): I have to admit to being a bit flabbergasted by the direction of this discussion of "The Personal Is Political" as racist and/or excluding Black women. I have been aware of many attacks on the what is called "Second Wave Feminism" by the ensuing "Waves" (particularly in Women's Studies) as white and middle class, but I wasn't aware that it was now going after some of the cornerstone ideas of our movement. -

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought

GOV 1029 Feminist Political Thought Tuesday, Thursday 12-1.15 Fall Semester 2018 Professor Katrina Forrester Office Hours: Tuesday, Thursday 2-3 Office: CGIS K437 E-mail: [email protected] Teaching Fellow: Leah Downey E-mail: [email protected] Course Description: What is feminism? What is patriarchy? What and who is a woman? How does gender relate to sexuality, and to class and race? Should housework be waged, should sex be for sale, and should feminists trust the state? This course is an introduction to feminist political thought since the mid-twentieth century. It introduces students to classic texts of late twentieth-century feminism, explores the key arguments that have preoccupied radical, socialist, liberal, Black, postcolonial and queer feminists, examines how these arguments have changed over time, and asks how debates about equality, work, and identity matter today. We will proceed chronologically, reading texts mostly written during feminism’s so-called ‘second wave’, by a range of influential thinkers including Simone de Beauvoir, Shulamith Firestone, bell hooks and Catharine MacKinnon. We will examine how feminists theorized patriarchy, capitalism, labor, property and the state; the relationship of claims of sex, gender, race, and class; the development of contemporary ideas about sexuality, identity, and gender; and how and whether these ideas change how fundamental problems in political theory are understood. 1 Course Requirements: Participation (25%) includes (a) active participation in discussion (15%); and (b) weekly responses: each week you will send 2-3 brief questions/ comments about the reading to your TF by 5pm the day before section (10%) Paper 1 (25%) 5-6 pages due October 18 4pm. -

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements By Laura K. Nelson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Robin Einhorn Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Laura K. Nelson 1 Abstract The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements by Laura K. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair This dissertation challenges the widely accepted historical accounts of women's movements in the United States. Second-wave feminism, claim historians, was unique because of its development of radical feminism, defined by its insistence on changing consciousness, its focus on women being oppressed as a sex-class, and its efforts to emphasize the political nature of personal problems. I show that these features of second-wave radical feminism were not in fact unique but existed in almost identical forms during the first wave. Moreover, within each wave of feminism there were debates about the best way to fight women's oppression. As radical feminists were arguing that men as a sex-class oppress women as a sex-class, other feminists were claiming that the social system, not men, is to blame. This debate existed in both the first and second waves. Importantly, in both the first and the second wave there was a geographical dimension to these debates: women and organizations in Chicago argued that the social system was to blame while women and organizations in New York City argued that men were to blame. -

Title of Thesis

Perplexities of the Personal and the Political How Women’s Liberation Became Women’s Human Rights Valgerður Pálmadóttir Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies Umeå 2018 This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) Dissertation for PhD ISBN: 978-91-7601-947-4. Cover illustrations: “When the photographer arrived, these women were undermining the patriarchy” and “Everywhere she went, there was a conference” by Björg Sveinbjörnsdóttir. Composition: In house Umeå University. Electronic version available at: http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: Umeå University Printing Service Umeå, Sweden 2018 To my family Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ......................................................................... v 1. Introduction ................................................................................ 1 Subversive Stories ...................................................................................................... 1 UN Conference on Women Provokes a Grassroots Response .................................4 New Strategies: Advocating for Women’s Human Rights at the UN .....................6 From Anger to Compassion .......................................................................................9 Aims of the Study and Research Questions ................................................................... 13 Selection of sources ....................................................................................................... -

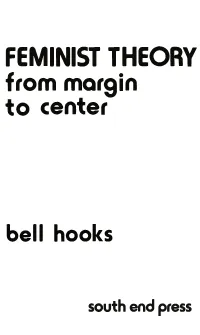

FEMINIST THEORY from Margin to Center

FEMINIST THEORY from margin to center bell hooks south end press Copyright © 1984 by bell hooks Copyrights are still required for book production in the United States. However, in our case it is a disliked necessity. Thus, in any properly footnoted quotation of up to 500 sequential words may be used without permission, as long as the total number of words quoted does not exceed 2000. For longer quo tations or for greater volume of total words, authors should write for permission to South End Press. Typesetting and production at South End Press. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hooks, Bell. Feminist theory from margin to center. Bibliography: p. l.Feminism-United.States-Evaluation. 2.Afro American women-Attitudes. 3. Marginality, Social-United States. I. Title. HQ1426.H675 1984 305.4'2'0973 84-50937 ISBN 0-89608-222-9 ISBN 0-89608-221-0 (pbk.) Cover design by Sharon Dunn South End Press 116 St. Botolph St. Boston, Ma. 02115 Printed In The U.S. For us sisters-Angela, Gwenda, Valeria, Theresa, Sarah For all we have shared for all we have come through together for continuing closeness table of contents Acknowledgments vii Preface ix Chapter 1 Black Women: Shaping Feminist Theory 1 Chapter 2 Feminism: A Movement to End Sexist Oppression 2 Chapter 3 The Significance of Feminist Movement 33 Chapter 4 Sisterhood: Political Solidarity Between Women 43 Chapter 5 Men: Comrades in Struggle 67 Chapter 6 Changing Perspectives on Power 83 Chapter 7 Rethinking the Nature of Work 95 Chapter 8 Educating Women: A Feminist Agenda 107 Chapter 9 Feminist Movement to End Violence 117 Chapter 10 Revolutionary Parenting 133 Chapter 11 Ending Female Sexual Oppression 147 Chapter 12 Revolution: Development Through Struggle 157 Notes 164 Bibliography 171 acknowledgments Not all women, in fact, very few have had the good fortune to live and work among women and men actively involved in feminist movement. -

The Role of the Next Generation in Shaping Feminist Legal Theory

Janus Proof Copy (Do Not Delete) 9/10/2013 2:13 PM Finding Common Feminist Ground: The Role of the Next Generation in Shaping Feminist Legal Theory KATHLEEN KELLY JANUS* This article explores the ways in which current feminist frameworks are dividing the women’s movement along generational lines, thereby inhibiting progress in the struggle for gender equality. Third-wave feminists, or the generation of feminists that came of age in the 1990s and continues today, have been criticized for focusing on personal stories of oppression and failing to influence feminist legal theory. Yet this critique presupposes that third-wave feminism is fundamentally different from the feminism of past generations. In contrast, this article argues that third-wave feminism is rooted in the feminist legal theory developed in the prior generation. This article demonstrates that the third-wave appears to be failing to influence feminist legal theory not because it is theoretically different, but because third-wave feminists approach activism in such a different way. For example, third-wavers envision “women’s issues” broadly, and rely on new tactics such as online organizing. Using the case study of Spark, a nonprofit organization employing third-wave activism to support global grassroots women’s organizations, this article provides a model of this new brand of feminism in practice. This article proposes the adoption of social justice feminism, which advocates casting a broader feminist net to capture those who have been traditionally neglected by the women’s movement, such as low-income women and women of color. Social justice feminism is a way to broaden the focus from a rights-based approach to an examination of the dynamics of power and privilege that continue to shape women’s lives even when legal rights to equality have been won. -

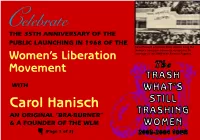

Trash Can Brochure

Celebrate THE 35TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PUBLIC LAUNCHING IN 1968 OF THE Carol Hanisch and three other women hang the Women’s Liberation banner to disrupt live TV Women’s Liberation coverage at the 1968 Miss America Pageant. Movement The TRASH WITH WHAT’SWomen’s Liberation Freedom Carol Hanisch TrashSTILL Can AN ORIGINAL “BRA-BURNER” TRASHING & A FOUNDER OF THE WLM ☛ WOMEN (Page 1 of 3) 2003-2004 TOUR BUILDING ON WHAT’S BEEN WON IN A KEYNOTE SPEECH, Carol will give her personal account of the historic Miss America Pageant Protest. She will discuss the actions and theory of the early WLM and what can be learned from them for the ongoing stuggle. Invite Carol Hanisch A FREEDOM TRASH CAN was used on September 7, 1968, when a group of more to your campus to tell her story of the than 150 feminists protested the Pageant in daring defiance of both beauty contests Women’s Liberation Movement’s and women’s limited place in society. beginnings, including the 1968 protest The women set up a picket line on the Atlantic City Boardwalk, carrying home-made of the Miss America Pageant. signs with such messages as, “Can Make-Up Hide the Wounds of Our Oppression?” They also did street theater: crowning a live sheep Miss America, chaining themselves to a large red, white and blue puppet of Miss America, and throwing “instruments of Participate female torture” into a Freedom Trash Can. Among the items they tossed were girdles, in an updated re-creation of a portion of high heels, nylons and garter belts, false eyelashes, hair curlers, dishrags, Playboy that milestone event by inviting women and Good Housekeeping magazines—and yes, several bras, though none were to bring what they feel most trashed by burned, contrary to popular myth.