World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

147AV4-1.Pdf

بسم هللا إلرمحن إلرحمي إمجلهورية إ لسﻻمية إملوريتانية رشف إخاء عدل إلوزإرة إ ألوىل إلس نة إجلامعية 2019-2018 إللجنة إلوطنية للمسابقات جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240 وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي حمرض مدإولت إلتأأمت جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي، يــــوم إلسبت إملوإفق 08 دمجرب 2018 عند إلساعة إلثانية عرشةزوالا يف قاعة الاجامتعات ابملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي؛ حتت رئاســـة إلسيـــد/ أبوه ودل محمدن ودل بلبﻻ ،ه انئب رئيس إللجنة - وحبضــور أإلعضاء إملعنيني، وبعد تقدمي إلسكراتراي لنتاجئ إملسابقة أابلرقـــــام إلومهية مرتبة ترتيبا إس تحقاقيا، ذكرت إلسكراتراي جلنة إلتحكمي بعــدد إملقاعد إملطلوبة من لك شعبة، وبعد نقاش مس تفيض لنتاجئ لك بةشع عىل حدة مت إعﻻن إلناحجني حسب إلرتتيب الاس تحقايق يف لك شعبة، فاكنت إلنتاجئ عىل إلنحو إلتايل : أول : أساتذة إ لعدإدية : I- Professeurs de Collège - شعبة : إلعربية وإلرتبية إ لسﻻمية - (Ar+IR) - إلناجحون حسب إلرتتيب إ لس تحقايق Liste des admis par ordre de mérite - إلرتتيب رمق إلندإء إ لمس إلاكمل اترخي وحمل إمليﻻد إملﻻحظات إ لس تحقايق 1 0141 يحظيه النعمة اباه 1993/12/31 تنحماد 2 0001 عبد الرحمن محمدن موسى سعدنا 1991/12/31 تكند 3 0722 امنه محمد عالي ببات 1987/08/10 السبخة 4 0499 عبد الرحمن محمد امبارك القاضين 1993/01/01 السبخه 5 0004 الغالي المنتقى حرمه 1992/12/31 اوليكات 6 0145 محمد سالم محمدو بده 1984/12/04 الميسر 7 1007 محمد عالي محمد مولود الكتاب 1996/09/03 العريه 8 0536 ابد محمد سالم محمد امبارك 1992/12/31 بتلميت 9 0175 محمد محمود ابراهيم الشيخ النعمه 1982/10/29 اﻻك 10 0971 الطالب أحمد جدو سيد إبراهيم حمادي 1995/12/16 اغورط 11 0177 محمد اﻻمين احمد شين 1982/12/31 -

2. Arrêté N°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ Du 24 Août 2006 Fixant Le Nombre De Conseillers Au Niveau De Chaque Commune

2. Arrêté n°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ du 24 août 2006 fixant le nombre de conseillers au niveau de chaque commune Article Premier: Le nombre de conseillers municipaux des deux cent seize (216) Communes de Mauritanie est fixé conformément aux indications du tableau en annexe. Article 2 : Sont abrogées toutes dispositions antérieures contraires, notamment celles relatives à l’arrêté n° 1011 du 06 Septembre 1990 fixant le nombre des conseillers des communes. Article 3 : Les Walis et les Hakems sont chargés, chacun en ce qui le concerne, de l’exécution du présent arrêté qui sera publié au Journal Officiel. Annexe N° dénomination nombre de conseillers H.Chargui 101 Nema 10101 Nema 19 10102 Achemim 15 10103 Jreif 15 10104 Bangou 17 10105 Hassi Atile 17 10106 Oum Avnadech 19 10107 Mabrouk 15 10108 Beribavat 15 10109 Noual 11 10110 Agoueinit 17 102 Amourj 10201 Amourj 17 10202 Adel Bagrou 21 10203 Bougadoum 21 103 Bassiknou 10301 Bassiknou 17 10302 El Megve 17 10303 Fassala - Nere 19 10304 Dhar 17 104 Djigueni 10401 Djiguenni 19 10402 MBROUK 2 17 10403 Feireni 17 10404 Beneamane 15 10405 Aoueinat Zbel 17 10406 Ghlig Ehel Boye 15 Recueil des Textes 2017/DGCT avec l’appui de la Coopération française 81 10407 Ksar El Barka 17 105 Timbedra 10501 Timbedra 19 10502 Twil 19 10503 Koumbi Saleh 17 10504 Bousteila 19 10505 Hassi M'Hadi 19 106 Oualata 10601 Oualata 19 2 H.Gharbi 201 Aioun 20101 Aioun 19 20102 Oum Lahyadh 17 20103 Doueirare 17 20104 Ten Hemad 11 20105 N'saveni 17 20106 Beneamane 15 20107 Egjert 17 202 Tamchekett 20201 Tamchekett 11 20202 Radhi -

Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project in Islamic Republic of Mauritania

Islamic Republic of Mauritania Ministry of Land Use, Urbanization and Habitation (MHUAT) Urban Community of Nouakchott (CUN) Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project In Islamic Republic of Mauritania Final Report Summary October 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) RECS International Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. PACET Corporation PASCO Corporation EI JR 18-105 Currency equivalents (interbank rates average of April to June 2018) USD 1.00 = MRU 355.049 USD 1.00 = MRO (obsolete) 35.5049 USD 1.00 = JPY 109.889 MRU 1.00 = JPY 3.0464 Source: OANDA, https://www.oanda.com Nouakchott City Urban Master Plan Development Project Final Report Summary Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives .............................................................................................................................. 2 Target Area ............................................................................................................................ 2 Target Year ............................................................................................................................. 3 Reports and Other Outputs .................................................................................................... 3 Work Operation Structure ...................................................................................................... 3 Part I: SDAU ............................................................................................................................... -

Liste Par Ordre Alphabétique Des Candidats Au Concours Élève Agent De Police Session 2017-2018 Retenus, Pour Subir Les Épreuves Du Sport

Liste par ordre alphabétique des candidats au concours élève agent de police session 2017-2018 retenus, pour subir les épreuves du sport N.D NNI NOM D N L N Centre 3630 2428055986 ABDELLAHI BARKA BILAL 09/05/1993 Aleg NDB 461 9803902036 ABDALLAHI CHEMAD M'BERGUENE 01/12/1991 KAEDI Kaedi 914 3587555380 ABDATT ALY NOUH 31/12/1994 BARKEOL Kaedi 2008 5120050426 ABDEL VETAH EL HASSEN ABEIDNA 31/12/1997 ATAR NDB 2679 1872262379 ABDELLAHI EL HASSEN BLEYEL 05/02/1995 KSAR NDB 1464 6606165213 ABDELLAHI MOHAMED H'MEINA 08/11/1996 TIMBEDRA Aioun 3022 4323925642 ABDELLAHI SIDI MAHMOUD LALAH 05/12/1989 MEDERDRA NDB 2041 2106682861 ABDERAHMANE ADAMA GREIGRA 31/12/1997 ROSSO NDB 2160 8925654336 ABDERRAHMANE ADAMA NGEME 15/07/1994 EL ARIA NDB 235 0490791968 ABDERRAHMANE BRAHIM AHMEDOU 02/12/1994 MAGTA LAHJAR Kaedi 1903 4467804675 ABDERRAHMANE CHEIKH KHOUWE 25/12/1997 BOUTILIMITT NDB 1256 5348715704 ABDERRAHMANE MOHAMED LEMINE EL ID 31/12/1994 BOUTILIMITT Aioun 110 6645174539 ABDERRAHMANE YAHYA EL ARBI 04/10/1995 TEYARETT Kaedi 378 3430303636 ABDOULLAYE MAMADOU WAGNE 25/02/1992 BABABE Kaedi 3490 9314626955 ABE CHEIKH AHMED 01/12/1994 TIMBEDRA NDB 2445 9591702411 ABIDINE MOUSSA MOHAMED 05/03/1996 SEBKHA NDB 324 2311953568 ABOU ABDALLAHI MED M'BARECK 16/02/1989 SEILIBABY Kaedi 606 1936874176 ABOUBEKRINE MED BILAL EBHOUM 30/12/1992 SEBKHA Kaedi 344 4585112886 ADAMA MOUSTAPHA SALLA 03/07/1990 SEBKHA Kaedi 4054 3264345754 AHME SALEM MOHAMED MOHAMED SALEM 28/02/1997 TEYARET NDB 3934 5877609271 AHMED ABDELLAHI YAGHLE 14/10/1994 BOUTILIMIT NDB 2688 5393921487 -

J.O. 1404F DU 15.01.2018.Pdf

JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ISLAMIQUE DE MAURITANIE BIMENSUEL Paraissant les 15 et 30 de chaque mois 15 Janvier 2018 60ème année N°1404 SOMMAIRE I – LOIS & ORDONNANCES II DECRETS, ARRETES, DECISIONS, CIRCULAIRES PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE Actes Divers 08 Décembre 2017 Décret n°531-2017 portant nomination à titre exceptionnel dans l’Ordre du Mérite National « ISTIHQAQ EL WATANI L’MAURITANI »……….7 19 Décembre 2017 Décret n°546-2017 portant nomination à titre posthume dans l’Ordre du Mérite National « ISTIHQAQ EL WATANI L’MAURITANI »………7 20 Décembre 2017 Décret n°547-2017 mettant fin aux fonctions d’un chargé de mission à la Présidence de la République……………………………………….7 1 Journal Officiel de la République Islamique de Mauritanie 15 Janvier 2018 1404 25 Décembre 2017 Décret n°548-2017 portant la ratification de l’accord de garantie du projet de Réhabilitation de l’Usine Guelb (1), signé le 18 Avril 2017 à Rabat, Royaume du Maroc entre la République Islamique de Mauritanie et le Fonds Arabe pour le Développement Economique et Social (FADES)………………………………………………………………7 25 Décembre 2017 Décret n°549-2017 portant la ratification de l’accord de prêt signé le 13 Mars 2017 entre la République Islamique de Mauritanie et le Fonds Africain de Développement (FAD), destiné au financement du Projet de Construction du Pont de Rosso………………………………………7 25 Décembre 2017 Décret n°550-2017 portant la ratification de l’accord de prêt signé le 18 Avril 2017 à Rabat, Royaume du Maroc entre la République Islamique de Mauritanie et le Fonds Koweitien pour le Développement -

Widespread Distribution of Plasmodium Vivax Malaria in Mauritania on the Interface of the Maghreb and West Africa Hampâté Ba1*, Craig W

Ba et al. Malar J (2016) 15:80 DOI 10.1186/s12936-016-1118-8 Malaria Journal RESEARCH Open Access Widespread distribution of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Mauritania on the interface of the Maghreb and West Africa Hampâté Ba1*, Craig W. Duffy2, Ambroise D. Ahouidi3, Yacine Boubou Deh1, Mamadou Yero Diallo1, Abderahmane Tandia1 and David J. Conway2* Abstract Background: Plasmodium vivax is very rarely seen in West Africa, although specific detection methods are not widely applied in the region, and it is now considered to be absent from North Africa. However, this parasite species has recently been reported to account for most malaria cases in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, which is a large country at the interface of sub-Saharan West Africa and the Maghreb region in northwest Africa. Methods: To determine the distribution of malaria parasite species throughout Mauritania, malaria cases were sampled in 2012 and 2013 from health facilities in 12 different areas. These sampling sites were located in eight major administrative regions of the country, within different parts of the Sahara and Sahel zones. Blood spots from finger- prick samples of malaria cases were processed to identify parasite DNA by species-specific PCR. Results: Out of 472 malaria cases examined, 163 (34.5 %) had P. vivax alone, 296 (62.7 %) Plasmodium falciparum alone, and 13 (2.8 %) had mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infection. All cases were negative for Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale. The parasite species distribution showed a broad spectrum, P. vivax being detected at six of the different sites, in five of the country’s major administrative regions (Tiris Zemmour, Tagant, Brakna, Assaba, and the capital Nouakchott). -

Rapport Sur Les Capacités Institutionnelles Des Communes Mauritaniennes

REPUBLIQUE ISLAMIQUE DE MAURITANIE Honneur-Fraternité-Justice MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Direction Général des Collectivités Territoriales Rapport sur les capacités Institutionnelles des communes mauritaniennes Janvier, 2017. 0 REPUBLIQUE ISLAMIQUE DE MAURITANIE Honneur-Fraternité-Justice MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION Direction Général des Collectivités Territoriales Rapport sur les capacités Institutionnelles des communes mauritaniennes 1 Table des matières Mot de Monsieur le Ministre de l’Intérieur et de la Décentralisation ............................................................... 3 Table des graphiques et diagrammes ..................................................................................................................... 4 Table des abréviations .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Résumé ....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................11 1. Mesure de Performance : genèse, contexte, objectifs et Méthodologie .....................................................13 A. Genèse et contexte de la MDP en Afrique de l’ouest ..........................................................................13 -

Malaria in Three Epidemiological Strata in Mauritania

Ouldabdallahi Moukah et al. Malar J (2016) 15:204 DOI 10.1186/s12936-016-1244-3 Malaria Journal RESEARCH Open Access Malaria in three epidemiological strata in Mauritania Mohamed Ouldabdallahi Moukah1*, Ousmane Ba2, Hampaté Ba2, Mohamed Lemine Ould Khairy3, Ousmane Faye4, Hervé Bogreau5,6,7, Frédéric Simard8 and Leonardo K. Basco5,6 Abstract Background: Malaria epidemiology in Mauritania has been characterized on the basis of epidemiological strata, defined by climatic and geographic features, which divide the country into three zones: Sahelian zone, Sahelo-Saha- ran transition zone, and Saharan zone. The association between geographic stratification and malaria transmission was assessed through a series of parasitological and entomological surveys. Methods: Surveys were conducted during the ‘cool’ dry season in 2011, ‘hot’ dry season in 2012, and rainy season in 2013 in a total of 12 sentinel sites. Finger-prick capillary blood samples were collected from children aged 2–9 years old in randomly selected households for microscopic examination and rapid diagnostic test for malaria. Adult mos- quitoes were sampled by pyrethrum spray catch and CDC light traps and identified using morphological keys and molecular tools. Results: Of 3445 children included, 143 (4.15 %) were infected with malaria parasites including Plasmodium falci- parum (n 71, 2.06 %), Plasmodium vivax (57, 1.65 %), P. falciparum-P. vivax (2, 0.06 %), Plasmodium ovale (12, 0.35 %), and Plasmodium= malariae (1, 0.03 %). A large majority of P. falciparum infections were observed in the Sahelo-Saharan zone. Malaria prevalence (P < 0.01) and parasite density (P < 0.001) were higher during the rainy season (2013), com- pared to cool dry season (2011). -

République Islamique De Mauritanie CARTE SANITAIRE NATIONALE DE LA MAURITANIE

République Islamique de Mauritanie Honneur – Fraternité – Justice Ministère de la santé CARTE SANITAIRE NATIONALE DE LA MAURITANIE 2014 Page 1 Page 2 PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................5 2. OBJECTIFS DE LA CARTE SANITAIRE .....................................................................................5 3. METHODOLOGIE ................................................................................................................5 4. SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE ET DEMOGRAPHIQUE .............................................................7 5. SYSTEME DE SANTE ............................................................................................................8 6. DONNEES NATIONALES ......................................................................................................9 7. 1. WILAYA DU HODH ECHARGHI (HEC) ...................................................................................... 15 7.1.3.1. MOUGHATAA DE NEMA .................................................................................................. 16 7.1.3.2. MOUGHATAA D’ AMOURJ ............................................................................................... 17 7.1.3.3. MOUGHATAA DE WALATA .............................................................................................. 18 7.1.3.4. MOUGHATAA DE TIMBEDRA .......................................................................................... -

BUEHLER-DISSERTATION-2013.Pdf (1.412Mb)

Copyright by Matthew J. Buehler 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Matthew J. Buehler certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Social Base of Divide-and-Rule: Left-Islamist Opposition Alliances in North Africa’s Arab Spring Committee: Jason Brownlee, Supervisor Catherine Boone Mounira Charrad Clement Henry Ami Pedahzur Joshua Stacher The Social Base of Divide-and-Rule: Left-Islamist Opposition Alliances in North Africa’s Arab Spring by Matthew J. Buehler, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2013 Dedication To my parents, Peggy and Mark Buehler Acknowledgements A number of people and institutions provided resources and guidance for me as I finished this dissertation. Without their support during my time at the University of Texas at Austin, I could not have brought this project to completion. Foremost, I’d like to thank my academic supervisor at the Department of Government, Professor Jason Brownlee, for his advice as I progressed through my doctoral training in political science. In his own research on Egypt, Jason shows the utmost passion, dedication, and meticulousness; I could not have had a better role model to emulate during my years at Texas. I will be eternally grateful. Professor Clement Henry provided exceptional mentoring during my doctoral studies, inspiring my interest in North Africa. He was always willing to share his wisdom with me, and I learned tremendously from his years of experience researching North African politics. -

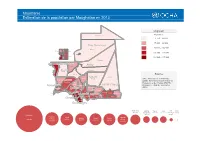

Mauritanie Estimation De La Population Par Moughataa En 2013

Mauritanie Estimation de la population par Moughataa en 2013 Légende Population Bir Mogrein 3 758 - 34 999 35 000 – 69 999 Tiris Zemmour 70 000 – 104 999 Teyare Ksar F'Derik t Tevragh Zeina Dar Naim Sebkha 105 000 – 139 999 Zoueratt Arafat El Mina Toujounine 140 000 – 175 000 Riyad Ouadane Dakhlet Nouadhibou Adrar Atar Nouadhibou Chinguity InchiriAkjoujt Source Aoujeft Tagant Oualata Tidjikja Tichitt Office Nationale de la Statistique Ouad Naga Trarza (ONS), Recensement Général de la Boutilimit Nouakchott Maghta Population et de l'Habitat (RGPH), Boumdeid Lahjar Hodh Charghi Nouakchott Moudjeria Programme élargi de vaccination Tamchekett (PEV) Mederdra Brakna R'Ki Aleg Guerrou Aioun z Boghe Barkeol Kiffa Hodh Rosso Bababe Monguel Timbedra Nema Keur-Macene M'Bagne Bassikounou M'BoutAssaba Tintane Gharbi Djigueni Kaed Ould Kankossa Kobeni i Amourj Gorgol Maghama Yenge Selibaby Guidimagha Guidimakha Dakhlet Tagant Adrar Tiris Inchiri 241 882 Nouadhibou 104 290 94 656 Zemmour 15 653 108 232 55 971 Nouakchott Hodh Ech Trarza Hodh El Brakna Gorgol Assaba Chargui 365 082 Gharbi 759 776 336 207 330 361 329 361 383 294 288 772 Mauritanie Estimation de la population par Moughataa et genre en 2013* Wilaya Moughataa Masculin Feminin Total Wilaya Moughataa Masculin Feminin Total Aoujeft 12 698 14 771 27 469 Aioun Al Atrouss 29 105 33 879 62 984 Atar 26 045 26 987 53 032 Koubenni 46 725 50 514 97 239 Adrar Hodh El Gharbi Chinguitti 4 188 4 937 9 125 Tamchekett 19 966 21 902 41 868 Ouadane 2 600 2 430 5 029 Tintane 40 567 46 114 86 681 Barkewol 40 205 -

Enforcing Mauritania's Anti-Slavery Legislation: the Continued Failure

report Enforcing Mauritania’s Anti-Slavery Legislation: The Continued Failure of the Justice System to Prevent, Protect and Punish Cover image: Haratine woman, Mauritania. Shobha Das/MRG. Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International This publication has been produced with the assistance of Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non- the Freedom Fund and the United Nations Voluntary Trust governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the Fund on Contemporary Forms of Slavery. The contents are rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and the sole responsibility of Minority Rights Group International, indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation Anti-Slavery International, Unrepresented Nations and and understanding between communities. Our activities are Peoples Organization and Society for Threatened Peoples. focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our Author worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent Rebecca Marlin, Minority Rights Group International. minority and indigenous peoples. Sarah Mathewson, Anti-Slavery International. MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 Editors countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, Carla Clarke, Minority Rights Group International. has members from 10 different countries. MRG has Peter Grant, Minority Rights Group International. consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Johanna Green, UNPO. Social Council (ECOSOC), and observer status with the Hanno Schedler, Society for Threatened Peoples. African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR). MRG is registered as a charity and a company MRG gratefully acknowledges the substantial research limited by guarantee under English law: registered charity no. assistance provided by Emeline Dupuis in the preparation of 282305, limited company no.