Mauritania Vulnerability Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER

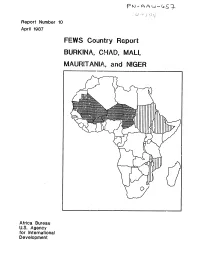

Report Number 10 April 1987 FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development Summary Map __ Chad lMurltanl fL People displaced by fighting High percentage of population have bothL.J in B.E.T. un~tfood needsa nd no source of income - High crop oss cobied with WESTERN Definite increases in retes of malnutrition at CRS centers :rom scarce mrket and low SAHARA .ct 1985 through Nov 196 ,cash income Areas with high percentage MA RTAI of vulnerable LIBYA MAU~lAN~A/populations / ,,NIGER SENEGAL %.t'"S-"X UIDA Areas at-risk I/TGI IEI BurkinaCAMEROON Areas where grasshoppers r Less than 50z of food needs met combined / CENTRAL AFRICAN would have worst impact Fi with absence of government stocks REPLTL IC if expected irdestat ions occur W Less than r59 of food needs met combined ith absence of government stocks FEYIS/PWA. April 1987 Famine Early Warning System Country Report BURKINA CHAD MALI MAURITANIA NIGER Populations Under Duress Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. April 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 2 Burkina 6 Chad 9 Mali 12 Mauritania 18 Niger 2f FiAures 3 Map 2 Burkina, Grain Supply and OFNACER Stocks 4 Table I Burkina, Production and OFNACER Stocks 6 Figure I Chad, Prices of Staple Grains in N'Djamcna 7 Map 3 Chad, Populations At-Risk 10 Table 2 Mali, Free Food Distribution Plan for 1987 II Map 4 Mali, Population to Receive Food Aid 12 Figure 2 Mauritania, Decreasing -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00002788 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (IDA-38100, IDA-38101, IDA-3810A and IDA-49330) ON A Public Disclosure Authorized CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR21.1 MILLION (US$32.15 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized SECOND MINING SECTOR CAPACITY BUILDING PROJECT June 13, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Sustainable Energy, Oil, Gas, and Mining Unit Sustainable Development Network AFCF1 Africa Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 15, 2014) Currency Unit = Mauritania Ouguiya (MRO) MRO 1.00 = US$ 0.0034 US$ 1.00 = MRO 298 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Bpd Barrels per day CAS Country Assistance Strategy CNITIE Comité National de l’Initiative pour la Transparence dans les Industries Extractives CNRE Centre National des Ressources en Eau CPPR Country Portfolio Performance Review DMG Direction des Mines et de la Géologie EI Extractive Industries EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative GIRM Government of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania GIZ Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit ICR Implementation Completion Report IDA International Development Association IDB Islamic Development Bank LED Local Economic Development IMF International Monetary Fund M&E Monitoring and evaluation MMI Ministère des Mines et de l’Industrie MPEM Ministère du Pétrole, de l’Energie et des Mines NORAD Norwegian Agency for development Cooperation PAD Project Appraisal Document -

Phase 2 Environmental Impact Assessment On-Site Mine Process

Tasiast Mauritanie Limited SA Tasiast Gold Mine Expansion Project Phase 2: On-Site Mine, Process and Infrastructure Environmental Impact Assessment Final 30 March 2012 Prepared for Prepared for Tasiast Mauritanie Limited SA Tasiast Gold Mine Expansion Project Revision Schedule Phase 2 Environmental Impact Assessment 30 March 2012 Final Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 21/12/2011 Draft for review Reine Loader Julie Raynor Russell Foxwell Environmental Consultant Associate Associate Fraser Paterson Associate 02 01/03/2012 Draft for Reine Loader Julie Raynor Russell Foxwell translation Environmental Consultant Associate Associate Fraser Paterson Associate 03 30/03/2012 FINAL Reine Loader Fraser Paterson Russell Foxwell Environmental Consultant Associate Associate URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited 6-8 Greencoat Place London SW1P 1PL United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 20 7798 5000 Fax +44 (0) 20 7798 5001 www.ursglobal.com Tasiast Mauritanie Limited SA Tasiast Gold Mine Expansion Project Limitations URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“URS”) (formerly URS Scott Wilson Ltd) has prepared this Report for the use of Tasiast Mauritanie Limited SA (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary, URS acknowledge that the Report may be disclosed by the Client to any third party, including members of the public for the specific purposes which have been advised to URS. URS shall not have any liability to any third parties for the unauthorised copying and any subsequent reliance on this Report. -

World Bank Document

, _ E~~~~~~S"/?91 / 2 3 Ene f Seient P Public Disclosure Authorized Flia @]~~~- 1 ,1 0 Public Disclosure Authorized Elements of Household E RnergyStrategy Report Nio. 123/90 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 4' ) ENERGYSECTOR MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM PURPOSE TheWorid Bank/UNDP/Bilateral Aid EnergySector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) was launched in 1983 to complemnentthe EnergyAssessment Program which had beenestablished three years earlier. The Assessment Programwas designedto Identifythe most seriousenergy problems facing some 70 developingcountries and to propose remedialaction. ESMAPwas conceived,In part, as a preinvestnientfacility to help implement recommendationsmade during the courseof assessment.Today ESMAPis carryingout preinvestmentand prefeasibilityactivities in about60 countriesand is providinga wiis rangeof institutionaland policyadvice. The programplays a significantrole in the overallintemational effort to providetechnical assistance to the energysector of developingcountries. It attemptsto strengthenthe impactof bilateraland muilateralresources and private sector investmentThe findings and recommendations emerging from ESMAP country activities provide governments, donors, andpotential investors with the informationneeded to identifyeconomically and environmentally sound energy projects andto acceleratetheir preparationand implementation.ESMAP's policy and research work analyzing cross-country trendsand issuesIn specificenergy subsectors make an imporantcontribution in highlightingcritical -

Congressional Budget Justification 2015

U.S. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION Pathways to Prosperity “Making Africa’s Growth Story Real in Grassroots Communities” CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION Fiscal Year 2015 March 31, 2014 Washington, D.C. United States African Development Foundation (This page was intentionally left blank) 2 USADF 2015 CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION United States African Development Foundation THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION WASHINGTON, DC We are pleased to present to the Congress the Administration’s FY 2015 budget justification for the United States African Development Foundation (USADF). The FY 2015 request of $24 million will provide resources to establish new grants in 15 African countries and to support an active portfolio of 350 grants to producer groups engaged in community-based enterprises. USADF is a Federally-funded, public corporation promoting economic development among marginalized populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. USADF impacts 1,500,000 people each year in underserved communities across Africa. Its innovative direct grants program (less than $250,000 per grant) supports sustainable African-originated business solutions that improve food security, generate jobs, and increase family incomes. In addition to making an economic impact in rural populations, USADF’s programs are at the forefront of creating a network of in-country technical service providers with local expertise critical to advancing Africa’s long-term development needs. USADF furthers U.S. priorities by directing small amounts of development resources to disenfranchised groups in hard to reach, sensitive regions across Africa. USADF ensures that critical U.S. development initiatives such as Ending Extreme Poverty, Feed the Future, Power Africa, and the Young African Leaders Initiative reach out to those communities often left out of Africa’s growth story. -

Looters Vs. Traitors: the Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and Its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire

Looters vs. Traitors: The Muqawama (“Resistance”) Narrative, and its Detractors, in Contemporary Mauritania Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba and Francisco Freire Abstract: Since 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations in Mauritania, the controversy around the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has grown substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented level of media freedom has been the prop- agation of views defending the Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization. On the one hand, verbal and written accounts have emerged which paint certain groups and actors as French colonial power sympathizers. At the same time, various online publications have responded by seriously questioning the very existence of a structured resistance to colonization. This article, drawing pre- dominantly on local sources, highlights the importance of this controversy in study- ing the western Saharan region social model and its contemporary uses. African Studies Review, Volume 63, Number 2 (June 2020), pp. 258– 280 Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba is Professor of History and Sociolinguistics at the University of Nouakchott, Mauritania (Ph.D. University of Provence (Aix- Marseille I); Fulbright Scholar resident at Northwestern University 2012–2013), and a Senior Research Consultant at the CAPSAHARA project (ERC-2016- StG-716467). E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Freire is an Anthropologist (Ph.D. Universidade Nova de Lisboa 2009) at CRIA–NOVA FCSH (Lisbon, Portugal). He is the Principal Investigator of the European Research Council funded project CAPSAHARA: Critical Approaches to Politics, Social Activism and Islamic Militancy in the Western Saharan Region (ERC-2016-StG-716467). -

147AV4-1.Pdf

بسم هللا إلرمحن إلرحمي إمجلهورية إ لسﻻمية إملوريتانية رشف إخاء عدل إلوزإرة إ ألوىل إلس نة إجلامعية 2019-2018 إللجنة إلوطنية للمسابقات جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240 وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي حمرض مدإولت إلتأأمت جلنة حتكمي إملسابقة إخلارجية لكتتاب 240وحدة دلخول إملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي، يــــوم إلسبت إملوإفق 08 دمجرب 2018 عند إلساعة إلثانية عرشةزوالا يف قاعة الاجامتعات ابملدرسة إلعليا للتعلمي؛ حتت رئاســـة إلسيـــد/ أبوه ودل محمدن ودل بلبﻻ ،ه انئب رئيس إللجنة - وحبضــور أإلعضاء إملعنيني، وبعد تقدمي إلسكراتراي لنتاجئ إملسابقة أابلرقـــــام إلومهية مرتبة ترتيبا إس تحقاقيا، ذكرت إلسكراتراي جلنة إلتحكمي بعــدد إملقاعد إملطلوبة من لك شعبة، وبعد نقاش مس تفيض لنتاجئ لك بةشع عىل حدة مت إعﻻن إلناحجني حسب إلرتتيب الاس تحقايق يف لك شعبة، فاكنت إلنتاجئ عىل إلنحو إلتايل : أول : أساتذة إ لعدإدية : I- Professeurs de Collège - شعبة : إلعربية وإلرتبية إ لسﻻمية - (Ar+IR) - إلناجحون حسب إلرتتيب إ لس تحقايق Liste des admis par ordre de mérite - إلرتتيب رمق إلندإء إ لمس إلاكمل اترخي وحمل إمليﻻد إملﻻحظات إ لس تحقايق 1 0141 يحظيه النعمة اباه 1993/12/31 تنحماد 2 0001 عبد الرحمن محمدن موسى سعدنا 1991/12/31 تكند 3 0722 امنه محمد عالي ببات 1987/08/10 السبخة 4 0499 عبد الرحمن محمد امبارك القاضين 1993/01/01 السبخه 5 0004 الغالي المنتقى حرمه 1992/12/31 اوليكات 6 0145 محمد سالم محمدو بده 1984/12/04 الميسر 7 1007 محمد عالي محمد مولود الكتاب 1996/09/03 العريه 8 0536 ابد محمد سالم محمد امبارك 1992/12/31 بتلميت 9 0175 محمد محمود ابراهيم الشيخ النعمه 1982/10/29 اﻻك 10 0971 الطالب أحمد جدو سيد إبراهيم حمادي 1995/12/16 اغورط 11 0177 محمد اﻻمين احمد شين 1982/12/31 -

Text Begins Here

SECRETARIAT - 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland - TEL: +41 22 791 6033 - FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www.actalliance.org Appeal Mauritania Support to People Affected by Drought in Mauritania and Senegal and to the Malian Refugees in southern Mauritania-MRT121 Appeal Target: US$ 3,039,387 Balance Requested: US$ 2,711,036 Geneva, 6 March 2012 Dear Colleagues, Mauritania and the neighbouring countries (mainly Mali and Senegal) have been affected by the ongoing Sahel food crisis characterised by food insecurity and malnutrition due to drought and other underlying factors in the region. It has been projected that 800,000 people in Mauritania, will need humanitarian assistance in 2012. In addition to the drought situation, the ongoing armed conflict in Northern Mali has forced thousands of Malians to cross the border to Mauritania. The drought and conflict have negatively impacted the entire Sahel Region resulting to hunger, malnutrition, displacement of people, destruction of local economies/livelihoods, pressure on limited existing food and water resources, increase of insecurity and violence. ACT member, LWF/DWS will respond to the drought situation in Mauritania, Fatick region of Senegal and provide assistance to the Malian refugees in Mauritania by working through local partners. The local partners include: ARDM, AU SECOURS and BSF in Mauritania, and Lutheran Church in Senegal (ELS) in Senegal’s Fatick region. This appeal will supplement the Mauritania government’s emergency response plan called ‘’EMEL’’ (hope). The project target is 8,653 households including: 4,206 drought affected households from Mauritania, 1,447 drought affected Households in Senegal and 3,000 Malian Refugees’ Households. -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N Akjoujt ! U479 ATLANTIC OCEAN U Uu435

! ! 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W Laayoune / El Aaiun .! !(Smara ! ! Cabo Bu Craa Bojador!( Western Sahara 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Distances shown in the table and the map are indicative. They have been calculated following the shortest route on main roads. Tracks have not been considered as a main road. Ad Dakhla (! Tiris Zemmour Algeria !( Zouerate ! Bir Gandus Nouadhibou Adrar !( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa (! ! Atar Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N Akjoujt ! u479 ATLANTIC OCEAN u uu435 Tagant Tidjikja ! Nouakchott uu9 Hodh Ech Chargui (! Nbeika Nouakchott Trarza ! uu157 Boutilimit Magta` Lahjar uu202 ! ! uu346 uu101 Aleg ! Mal (! ! u165 Brakna u !Guerou Bourem uu6 Bogue Kiffa 'Ayoun el 'Atrous Nema Tombouctou! uu66 Rosso ! (! Assaba (! 210 (! (! uu 276 (!!( Tekane ! uu Goundam ! Richard-Toll !uu107 Lekseiba Timbedgha Gao Bababe ! Tintane ! !( ! Hodh El Gharbi ( uu116 !Mbout !( Kaedi uu188 Bassikounou Saint-Louis uu183 Bou Gadoum !( Gorgol (! Guidimaka !Hamoud !(Louga uu107 Bousteile! !( Kersani 'Adel Bagrou Tanal ! ! Niminiama (! Nioro Nara 15°0'0"N Thies Touba Gouraye Diadji ! 15°0'0"N Senegal ! Selibabi du Sahel Sandigui Burkina (! !( Douentza !( ! Sandare !( Mbake Khabou Guidimaka Salmossi Dakar .!Rufisque Faso 20°0'0"W Diourbel 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W !( !( !( Mopti Bandiagara ! Sikire Gorom-Gorom Mbour Kayes Niono! !( Linking Roads Road Network Date Created: ! 05 - DEC -2012 ! (! Reference Town National Boundar!y Map Num: LogCluster-MRT-007-A2 ! Primary Road ! Coord.System/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 -

Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N

!ho o Õ o !ho !h h !o ! o! o 20°0'0"W 15°0'0"W 10°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 0°0'0" Laayoune / El Aaiun HASSAN I LAAYOUNE !h.!(!o SMARAÕ !(Smara !o ! Cabo Bu Craa Algeria Bojador!( o Western Sahara BIR MOGHREIN 25°0'0"N ! 25°0'0"N Guelta Zemmur Ad Dakhla h (!o DAKHLA Tiris Zemmour DAJLA !(! ZOUERAT o o!( FDERIK AIRPORT Zouerate ! Bir Gandus o Nouadhibou NOUADHIBOU (!!o Adrar ! ( Dakhlet Nouadhibou Uad Guenifa !h NOUADHIBOU ! Atar (!o ! ATAR Chinguetti Inchiri Mauritania 20°0'0"N Mali 20°0'0"N AKJOUJT o ! ATLANTIC OCEAN Akjoujt Tagant TIDJIKJA ! o o o Tidjikja TICHITT Nouakchott Nouakchott Hodh Ech Chargui (!o NOUAKCHOTT Nbeika !h.! Trarza ! ! NOUAKCHOTT MOUDJERIA o Moudjeria o !Boutilimit BOUTILIMIT ! Magta` Lahjar o Mal ! TAMCHAKETT Aleg! ! Brakna AIOUN EL ATROUSS !Guerou Bourem PODOR AIRPORTo NEMA Tombouctou! o ABBAYE 'Ayoun el 'Atrous TOMBOUCTOU Kiffa o! (!o o Rosso ! !( !( ! !( o Assaba o KIFFA Nema !( Tekane Bogue Bababe o ! o Goundam! ! Timbedgha Gao Richard-Toll RICHARD TOLL KAEDI o ! Tintane ! DAHARA GOUNDAM !( SAINT LOUIS o!( Lekseiba Hodh El Gharbi TIMBEDRA (!o Mbout o !( Gorgol ! NIAFUNKE o Kaedi ! Kankossa Bassikounou KOROGOUSSOU Saint-Louis o Bou Gadoum !( ! o Guidimaka !( !Hamoud BASSIKOUNOU ! Bousteile! Louga OURO SOGUI AIRPORT o ! DODJI o Maghama Ould !( Kersani ! Yenje ! o 'Adel Bagrou Tanal o !o NIORO DU SAHEL SELIBABY YELIMANE ! NARA Niminiama! o! o ! Nioro 15°0'0"N Nara ! 15°0'0"N Selibabi Diadji ! DOUTENZA LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR INTL Thies Touba Senegal Gouraye! du Sahel Sandigui (! Douentza Burkina (! !( o ! (!o !( Mbake Sandare! -

(Pdc) – Koumbi Saleh République Islamique De Maur

PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT COMMUNAL (PDC) – KOUMBI SALEH RÉPUBLIQUE ISLAMIQUE DE MAURITANIE Honneur – Fraternité – Justice Wilaya du Hodh el Chargui Moughataa de Timbedra Commune rurale de KOUMBI SALEH PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT COMMUNAL DE LA COMMUNE RURALE DE KOUMBI SALEH Financement de la Commission Européenne Contrat N° DCI-NSAPVD/2009/218662 Projet ANEHECH -Terre Solidali Onlus Page 1 PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT COMMUNAL (PDC) – KOUMBI SALEH SOMMAIRE 1- Présentation générale de la Commune de KOUMBI SALEH ........................................ 3 Localisation, date de création et origine ............................................................................................. 3 Milieu physique .................................................................................................................................. 4 Climat et pluviométrie: ....................................................................................................................... 4 Ressources en eau(eau de surface et eau souterraines) ...................................................................... 5 Solset ressources végétales ................................................................................................................. 6 Milieu humain .................................................................................................................................... 7 Taille et répartition spatiale de la population ..................................................................................... 7 Composition ethnique et organisation -

2. Arrêté N°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ Du 24 Août 2006 Fixant Le Nombre De Conseillers Au Niveau De Chaque Commune

2. Arrêté n°R2089/06/MIPT/DGCL/ du 24 août 2006 fixant le nombre de conseillers au niveau de chaque commune Article Premier: Le nombre de conseillers municipaux des deux cent seize (216) Communes de Mauritanie est fixé conformément aux indications du tableau en annexe. Article 2 : Sont abrogées toutes dispositions antérieures contraires, notamment celles relatives à l’arrêté n° 1011 du 06 Septembre 1990 fixant le nombre des conseillers des communes. Article 3 : Les Walis et les Hakems sont chargés, chacun en ce qui le concerne, de l’exécution du présent arrêté qui sera publié au Journal Officiel. Annexe N° dénomination nombre de conseillers H.Chargui 101 Nema 10101 Nema 19 10102 Achemim 15 10103 Jreif 15 10104 Bangou 17 10105 Hassi Atile 17 10106 Oum Avnadech 19 10107 Mabrouk 15 10108 Beribavat 15 10109 Noual 11 10110 Agoueinit 17 102 Amourj 10201 Amourj 17 10202 Adel Bagrou 21 10203 Bougadoum 21 103 Bassiknou 10301 Bassiknou 17 10302 El Megve 17 10303 Fassala - Nere 19 10304 Dhar 17 104 Djigueni 10401 Djiguenni 19 10402 MBROUK 2 17 10403 Feireni 17 10404 Beneamane 15 10405 Aoueinat Zbel 17 10406 Ghlig Ehel Boye 15 Recueil des Textes 2017/DGCT avec l’appui de la Coopération française 81 10407 Ksar El Barka 17 105 Timbedra 10501 Timbedra 19 10502 Twil 19 10503 Koumbi Saleh 17 10504 Bousteila 19 10505 Hassi M'Hadi 19 106 Oualata 10601 Oualata 19 2 H.Gharbi 201 Aioun 20101 Aioun 19 20102 Oum Lahyadh 17 20103 Doueirare 17 20104 Ten Hemad 11 20105 N'saveni 17 20106 Beneamane 15 20107 Egjert 17 202 Tamchekett 20201 Tamchekett 11 20202 Radhi