Spring 2020 CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parthenon, August 9, 1990

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Summer 8-9-1990 The Parthenon, August 9, 1990 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, August 9, 1990" (1990). The Parthenon. 2817. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/2817 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. · Ma r s ha I I •University Thursday . August 9, 1990 Cloudy, chance of rain, PARTHENON highs in upper 70s ·I.___ vo_l_. 90_, N_o_._1_1 s_ ___, Bush deploys U.S. forces to Middle East By The Associated Press and the restoration of the Kuwaiti govern tary leadership was settling in for what ment to power. could be a lengthy operation. \ U.S. forces at a glance President Bush announcedWednesday The president conceded that the Saudi "This whole thing isn't easy. You don't that U.S. troops were taking up "defensive defense mission "may take time and be deploy forces and they suddenly show up in The Pentagon reports the follow positions" in oil-rich Saudi Arabia to guard costly" and said he would consider tapping another part of the world. There are a hell Ing U.S. Navy forces have been de against a possible attack by Iraq. the nation's stra~c petroleum reserves of a lot of logistical problems that go into ployed to the · Mediterranean and "They will not initiate hostilities but they to assure a ready supply ofoil . -

Lop40* with Shadot Sleven~

'41~11~tla1~1 *lOP40* WITH SHADOt SlEVEN~ ***COMPACT DISC #1, TRACK 10, HAS 1KHZ REFERENCE TONE*** TOPICAL PROMO TOPICAL PROMO FOR SHOW #29 IS LOCATED ON CD DISC 4. TRACK 6 TOPICAL ON VINYL LOCATED AT THE END OF SIDE 4A DO NOT USE AFTER SHOW #29 1. WORTH THE STEP TO TAKE HOLD :28 Hi, Shadoe Stevens, AT40. Last week The New Kids On The Block spent a third week at #1 on the official Billboard chart with "Step By Step". But they've got to watch their step. Climbing up to #2 was Glenn Medeiros with Bobby Brown and "She Ain't Worth It". And moving up to #3 was the four-woman vocal group En Vogue with "Hold un==. Wlll rhe New Khi ... t.vp tlua chc.rt block? Will Glenn and Bobby find it's worth their while to be #1? Or will En Vogue take hold? Ah, D'Shadoe knows -- on American Top 40. 2. POISON DARTS, TIME JERKS. JANET COMES BACK :29 Hey, Shadoe Stevens on AT40. Last week saw debuts by tune titans in music. Those glam slam rockers, Poison, returned with a new song, "Unskinny Bop". coming in with the fifth hit from her mega-platinum album "Rhythm Nation" was Janet Jackf;on with a ballad called "Come Back To Me". And returning after five years was the reunited band that includes .ranet' s producers, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. The Time clocked into the countdown with "Jerk 11 Out • We've got the hottest hits, the hottest acts, and all the chart facts --· on American Top 40. -

“The Times They Are A-Changin'”: Flexible Meter and Text Expression in 1960S and 70S Singer-Songwriter Music by Nancy Eliz

“The Times They Are A-Changin’”: Flexible Meter and Text Expression in 1960s and 70s Singer-Songwriter Music by Nancy Elizabeth Murphy B.Mus., The University of Western Ontario, 2003 M.A., The University of Western Ontario, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2015 © Nancy Elizabeth Murphy, 2015 Abstract The 1960s and 70s saw the flowering of the singer-songwriter style, which featured acoustic performances by artists who were the composers and lyricists of their own music. Reflecting their culture, their songs carried messages of personal and political significance. But their music is of technical as well as of social interest. Like classical art song, it often highlights lyrical meaning with various sorts of metric irregularities. In this dissertation, I closely analyze twenty-seven songs by Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Joni Mitchell, and Cat Stevens, in order to characterize the metric style of their songwriting and demonstrate their use of meter as an expressive device. To describe meter in this music requires theories more flexible than those usually applied to groove-based music. The analyses in this dissertation draw not only from theories of meter as a hierarchy of beat streams, but also upon theories of metrical process and prosody, in order to create transcriptions, to describe precisely listeners' sensations of meter, and to propose expressive rationales for metric settings. As an introduction to the style and the theoretical issues, Chapter 1 considers the problems of conceiving of meter in the expressively timed context of Mitchell’s “The Fiddle and the Drum.” Chapter 2 examines the existing methods for analyzing meter in music and poetry, in order to find some productive ways to analyze this metrically fluctuant repertoire. -

Reclaiming Critical Analysis: the Social Harms of “Bitch”

Reclaiming Critical Analysis: The Social Harms of “Bitch” BY SHERRYL KLEINMAN, MATTHEW B. EZZELL, AND A. COREY FROST Abstract The increasing use of “bitch” among women makes it harder to see links between the word and patriarchy. In pop culture and in everyday life, men and women use “bitch” as an epithet against women (and non-conventional men) as well as a means of expressing dominance over a person or object. Women who “reclaim” the term—by declaring themselves “bitches,” calling other women “bitches” in a friendly way, or using the term as a female-based generic—unwittingly reinforce sexism. Unlike the term “feminist,” which is tied to a movement for social change, “bitch” provides women only with false power, challenging neither men nor patriarchy. E USED TO BELIEVE that feminists found the term “bitch” unacceptable. Years ago, when one of us analyzed terms that make women invisible and men the norm—“freshman,” “chairman,” and “you guys”—she wrote, perhaps naively: “I’m not referring [in the case of sexist language] to such words as ‘bitch,’ ‘whore,’ and ‘slut.’ What I focus on instead are words that students Wconsider just fine: male (so-called) generics” (Kleinman 2000: 6). Unlike “you guys,” “bitch” is a slur; and there’s no doubt that the word has a female referent, and a non- human one at that.1 Feminists knew that women could act in mean-spirited ways, but we also knew that using “bitch” to describe them reinforced sexism. If women liked the feel of 1 We will focus on “bitch” in this paper, and make only passing references to “sluts” and “hos.” Some of our analysis could be applied to these terms as well. -

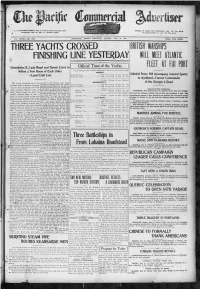

Three Battleships in Ahaina Roadstead from L

II" . S far 11 01 1 aSs s. WEATHER BUREAU, 19. 24 Q6 tj. Jnly Last Honrs' Rainfall, trace. SUGAR. Degree Test Centrifugals, 4.36c Per Ton, $87.20. Temperature, Max 80; Min. 70. Weather, cloudy. 83 Analysis Beets, lis. 7ud. Per Ton, $89.20. HjsTAttJMSHKD JULY 2, 1854. TERRITORY, MONDAY, JULY 20, 1908. VOL-- XLVHI, NO. 8095 HONOLULUL, HAWAII PRICE FIVE CENTS. BRITISH WARSHIPS WILL MEET ATLANTIC r v FLEET AT FIJI PORT Official of the Yachts Gwendolyn II., Lady Maud and Hawaii Come in Time The following are the complete statements of the time of the several yachts: Within a Few Hours of Each Other LURTJNE. y & Admiral Poore Will Accompany Admiral Local Craft Last. Finish Honolulu .... Juiy i Hours nun. 4dy2 see. Sperry Start San Pedro t. Juiy 4 IZ hours U'J nun. 00 sec. to Auckland Former Commander ' 13 days 21 hours 31 min. 43 V. sec. GWENDOLYN of the Georgia Is Dead. The second transpacific yacht race brought to the Nuuanu street wharf IL yesterday afternoon when the whistle u1y Ob sec. f from San Pedro to Honolulu was finish- Finish Honolulu hours 3s min. sounded for the sighting of the Hawaii. Start San Pedro July 4 12 hours 00 min. 00 sec. 1 ed at 3 o'clock, 23 minutes, and 30 sec- The launch which had just brought the i ! Lady Maud in, started out again with (Associated Press Cablegrams.) onds, yesterday afternoon, when the .the Yacht Committee aboard, augment- Elapsed time J aays zx nours ds mm. Ub sec. '- -f AUCKLAND, New Zealand, July 20. -

For Immediate Release: March 16, 2017 MORRIS DAY and THE

For more information contact: Adrenna Alkhas Marketing and Communication Director (209) 668-1333 ext. 340 – Office For Immediate Release: March 16, 2017 MORRIS DAY AND THE TIME BRING THE FUNK TO STANISLAUS COUNTY FAIR Turlock, CA (March 16, 2017) — Funk legends Morris Day and the Time bring their enduring swagger to Turlock for the 2017 Stanislaus County Fair. Morris Day and the Time will be performing Tuesday, July 18, 2017 at the Stanislaus County Fair on the Bud Light Variety Free Stage. The concert will be hosted by KWIN and will begin at 8:30 p.m. The concert is free with the price of Fair admission. “This funk group will get our Fair guests dancing in no time,” said Adrenna Alkhas, spokesperson for the Stanislaus County Fair. “It will be a great way to celebrate the legacy of longtime collaborator Prince.” Morris Day played an essential role in the development of the iconic pop-funk sound of the 1980’s. His exuberant stage presence and colorful showmanship mirror that of longtime friend Prince. Day’s involvement with Prince traces back to 1980 when his composition “Party up,” originally recorded when he was a member of the Enterprise, was covered on Prince’s album “Dirty Mind.” As a founding member of Prince’s band the Time, Day remains a true funk trailblazer. He worked with the group until 1984 when he launched his solo career, before returning in the 1990’s. The Timegained popularity with feel-good tracks such as “Jerk Out” and “Jungle Love.” In fact, “Jungle Love” was featured in Prince’s 1984 film Purple Rain. -

Losing Charlotte / Heather Clay.—1St Ed

For Nick And gratia Jenny PROLOGUE CHARLOTTE WAS SPEAKING to her already. Not waiting there, in the dark, for Knox to crest out of sleep, but already talking, low and fast. Knox rubbed her ears, blinked, and tried to sit up. Her nightgown ticked against the sheet, making the brief flash of static that Knox thought of as “bed lightning”—Charlotte’s words. Charlotte had words that Knox tried to resist, but couldn’t. She was a shape, hunched over Knox and saying I’m going now, I’m meeting Cash, go back to sleep. Don’t go, Knox thought. But what she said was: Don’t tell me. I told you I don’t want to know. Stop telling me. It’s not like I’m having sex with him, Charlotte said. Shut up, Knox whispered. He hasn’t asked me. I think he’s scared. He’s only fifteen. Knox’s attempt to laugh quietly, incredulously, sounded like a hiss. So are you, she said. Charlotte wiggled her shoulders a little. Maybe tonight’s the night, she said. If I feel like it. You never know. Hold down the fort for me. Why are you acting like this, Knox said. Charlotte never answered questions like that. Why would she? She lifted herself off the bed, crossed the room, and let herself into the hall so quietly that Knox hated her even more, hated that her talent for stealth was just another admirable thing about her, among too many. Wish me luck, Charlotte said, her head appearing briefly around the jamb, then dissolving into the dark again. -

MONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 210 164 SE 035 841 AUTHOR Boggess, Gary V. - TITLE Integrated Science=Mathematics Education Project (ISMEP). Set of Modules. INSTITUTION_ Murray State Univ., Ky. MONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 ..GRANT NSF-SER-76-14851 NOTE 726p.: Not available in paper bopy due to marginal legibility of original document. N, .EDES PRICE Kroll Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDES. DESCRIPTORS Course Content: Course Descriptions: Elementary. School Mathematics: *Elementary School Science: Higher Education: Inservice Teacher Educaticn: *Mathematics Curriculum: Mathematics' Education; *Preservice Teacher Education: *Science Course Isprovemant_Projectst Science Education: *Teacher Education Curriculum 1BSTPAcT The Integrated Scietc -Mathem tics Education Project (IMP) is an NSF-funded, interdisciplin r science /mathematics edmcation proems for preservice elementary school teachers which fosters an increase in scientific and mathematical literacy, improved attitudes toward science and mathematics, and enhancement of intellectual development on the part of classroom teachers and public -school pupils. /SMEP courses: blend scientific, mathematical, and educational components while providing classrOom, labcratory, and practicu experiences relevant to elementary school programs. Although-an overview of the project, organizational flow chart, checklists, brochure's, and an evaluation report are included, the major portion of the document is devoted to the odules_used in the program. Individual's modules containobje'ctives, instructilicnal references and materials, procedures, and assessment critetia. 'Sources used in the modules include activities from the "Science Course Improvement Study" and "Science A Process Approach," and other elementary science and mathematics curriculum projects. (Author/DS) *********************************************************************** .41 Reproductions supplied by !DRS are.the best that can be made * . * . * , from the original document,. -

The Lost Songs of Somerville

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 The Lost Songs of Somerville Scott Cerreta CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/510 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Lost Songs of Somerville By Scott Cerreta 2 I And a one, a two, a one, two, three, four. Remember me? I used to be the face of America, at least according to the painted cover of a once famous magazine. You’ll remember the picture if I show it to you: I’m the kid in the middle with the chipped tooth, a small flag planted in one young fist and a dying sparkler in the other; I’m sitting on a grassy hill with my family and some neighbors and the picture’s perspective is that of being just downhill looking up at us; our faces, still glowing with wonder, are all staring up into a darkening evening sky filled with fireworks which are, at that moment, in exact full neon blossom. Can’t find the likeness? Well, it was a long time ago and though some of us do, I guess most of us don’t, as children, much resemble our eventual adult selves. Anyway, the face of America wasn’t really me, it was our town, Somerville, they were referring to, back when this country was still knowable enough that one could imagine its true essence being found in such a small and simple space. -

INVENTORY Decedcnt IZIORIGINAL [:1 AMENDED D SUPPLEMENTAL

10-PR-16-4610'PR'1646 Filed in First Judicial District Court 1/4/2017 2:38:15 PM Carver County, MN STATE OF MINNESOTA FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT DISTRICT COURT COUNTY OF CARVER PROBATE DIVISION Court File No. 10-PR-16-46 Estate of ' Prince Rogers Nelson, INVENTORY Decedcnt IZIORIGINAL [:1 AMENDED D SUPPLEMENTAL Date of Death: April 21, 2016 Bremer Trust, N ationai Association, the Personal Representative of the Estate, states: 1. The following is a true and correct inventory at date of death values of all the property of the Estate, both real and personal, which has come into my possession as Personal Representative. If an appraisal of any asset has been made, the name and address of each appraiser used is included. After diligent search and inquiry concerning the assets of the Estate, the following is a list of the Estate assets by category: SCHEDULE VALUE Schedule A: Real Estate $ 25,431,900.00 Schedule B: Stocks, Bonds, and Other Securities $ 0.00 Schedule C: Bank Accounts, Mortgages, Contracts for Deed, Notes and Cash $ 110,080.51 Schedule D: Other Personal Property $ 836,166.70 SUBTOTAL $ TBD Less Schedule E: Mortgages and Liens $ 0.00 TOTAL 35 TBD 2. A copy of this Inventory, including all schedules, has been mailed to the surviving spouse, if any, and to all rcsiduary distributees of the Decedent and to interested persons and creditors who have requested a copy of the Inventory. MlNN. STAT. § 5243-706 P600 Inventory MNCLE © 20 l 6 I l 30455590 001 10-PR-16-461 0 _ PR _ 1646 Filed in First Judicial District Court 1/4/2017 2:38:15 PM Carver County, MN Under penalties for perjury, I declare or affirm that I have read the Inventory and I know or believe its representations are true and complete. -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

The Stepcrew

SEASON CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 2011–2012 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2011–2012 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. SEASON YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. SEASON CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. ENCORE Beth Anderson Rodolfo Chavez Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Hedy Harrison-Anduha and Liming Chen Jose Iturbi Foundation Larry Anduha Wanda Chen National Endowment for the Susan and Clifford Asai Margie and Ned Cherry Arts Larry Baggs Frances and Philip Chinn Eleanor and David St. Clair Marilyn Baker Nancy and Lance Chontos Terry Bales Patricia Christie HEADLINER Sallie Barnett Richard Christy The Capital Group Companies Alan Barry Rozanne and James Churchill Charitable Foundation Cynthia Bates Neal Clyde Chamber Music Society of Dennis Becker Mark Cochrane Detroit Barbara S. Behrens Michael Cohn The Gettys Family Aldenise Belcer Claire Coleman Los Cerritos Center Yvette Belcher Mr.