The Waterside Workers' Federation Film Unit, 1953 - 1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reckoning, by Robert W

1 CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI The Reckoning, by Robert W. Chambers 2 The Reckoning, by Robert W. Chambers The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Reckoning, by Robert W. Chambers This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Reckoning Author: Robert W. Chambers Release Date: May 12, 2008 [EBook #25441] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RECKONING *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net [Illustration: Elsin Grey.] The RECKONING BY ROBERT W. CHAMBERS The Reckoning, by Robert W. Chambers 3 AUTHOR OF "CARDIGAN," "THE MAID-AT-ARMS," "THE KING IN YELLOW," ETC. NEW YORK A. WESSELS COMPANY 1907 Copyright, 1905, by ROBERT W. CHAMBERS Published September, 1905 PRESS OF BRAUNWORTH & CO. BOOKBINDERS AND PRINTERS BROOKLYN, N.Y. PREFACE The author's intention is to treat, in a series of four or five romances, that part of the war for independence which particularly affected the great landed families of northern New York: the Johnsons, represented by Sir William, Sir John, Guy Johnson, and Colonel Claus; the notorious Butlers, father and son; the Schuylers, Van Rensselaers, and others. -

Z432 Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia, Federal Office Deposit

Z432 Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia, Federal Office deposit 6 Download list Amended July 2008 _______________________________________________________________ ANU ARCHIVES PROGRAM Telephone: +61 2 6125 2219 Noel Butlin Archives Centre Facsimile: +61 2 6125 0140 Email: [email protected] Incorporating the ANU Archives of Business & Labour Web: www.archives.anu.edu.au and the National AIDS Archive Collection WATERSIDE WORKERS FEDERATION Deposit No. Z432: Federal Office SITE LIST Receipt Dates Quantity Location 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel (D1-D5) Stack 294-295 5 May 1992 12 cartons (D6-14) Stack 294-295 27 May 1992 9 cartons & 1 archives box (4-13) Stack 294-295 11 Nov 1992 69 cartons & 1 parcel (14-78) Stack 294-295 21 Dec 1992 2 cartons (80-81- No 79) Stack 294-295 18 May 1993 18 cartons Stack 294-295 13 Jul 1994 2 parcels Stack 294-295 13 Jun/23 Dec 1996 1 bundle (82-86) Stack 294-295 Notes: 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel of donated ACTU material – circulars and Executive minutes (cartons D1 to D5) 5 May 1992 12 cartons containing donated material – newspaper clippings and ACTU Bulletins and Newsletters (cartons numbered D6 to D14) and copies of Port News in cartons 1-3 (Boxes 1-3) 27 May 1992 9 cartons and 1 archives box containing miscellaneous material, rules, instruction booklets, published histories, circulars and records of N. Docker. Records of CH Fitzgibbon were also sent, but these were removed to his personal collection at P101 (remaining cartons numbered Boxes 4-13) 11 Nov 1992 65 cartons and 1 parcel. -

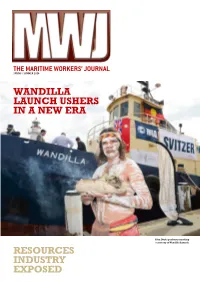

Wandilla Launch Ushers in a New Era Resources

THE MARITIME WORKERS’ JOURNAL SPRING / SUMMER 2014 WANDILLA LAUNCH USHERS IN A NEW ERA Glen Doyle performs smoking ceremony at Wandilla Launch. RESOURCES INDUSTRY EXPOSED p00_Cover.indd 1 19/11/13 9:07 AM CONTENTS 6 - 13 National Council: A meeting of minds 14 & 15 Chevron Campaign: BIS Shrapnel report shows resource industry loose with the truth 22 & 23 Vale Jimmy Tannock: Remembering retired National Deputy Secretary 35 Wandilla Launch: Tugboat signals beginning of new training initiative 41 Credit Union: MMPCU relocates as part of expansion 42 Financial Reports: MUA Concise Financial Report 2013 44 Dispute: Egyptian seafarers have a win in Kembla EDITOR IN CHIEF Paddy Crumlin COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Jonathan Tasini EDITORIAL TEAM Ashleigh Telford Greig Kelbie DESIGN Magnesium Media PRINTER Printcraft Maritime Workers’ Journal 365-375 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Contact: 9267 - 9134 Fax: 9261 - 3481 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mua.org.au MWJ reserves the right at all times to edit and/or reduce any articles or letters to be published. Publication No: 1235 MUA members out in force to celebrate World Maritime Day at the For all story ideas, letters, obituaries please email Australian National Maritime Museum on Darling Harbour. [email protected] LOGGING ON LOGGING ON world economy down the toilet. The company negotiated an EBA without and Port of Convenience campaigns are Who knows really, because the Libs never telling its workforce what it was up to. illustrative of the capacity of international LOGGING had to say anything in opposition? The little Patrick, then, compounded this moral lapse maritime workers to effectively network in time Abbott has been in office doesn’t look by using a type of guerrilla management pursuing justice and accountability in the promising, though. -

Australian Radio Series

Radio Series Collection Guide1 Australian Radio Series 1930s to 1970s A guide to ScreenSound Australia’s holdings 1 Radio Series Collection Guide2 Copyright 1998 National Film and Sound Archive All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. First published 1998 ScreenSound Australia McCoy Circuit, Acton ACT 2600 GPO Box 2002, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6248 2000 Fax (02) 6248 2165 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.screensound.gov.au ISSN: Cover design by MA@D Communication 2 Radio Series Collection Guide3 Contents Foreword i Introduction iii How to use this guide iv How to access collection material vi Radio Series listing 1 - Reference sources Index 3 Radio Series Collection Guide4 Foreword By Richard Lane* Radio serials in Australia date back to the 1930s, when Fred and Maggie Everybody, Coronets of England, The March of Time and the inimitable Yes, What? featured on wireless sets across the nation. Many of Australia’s greatest radio serials were produced during the 1940s. Among those listed in this guide are the Sunday night one-hour plays - The Lux Radio Theatre and The Macquarie Radio Theatre (becoming the Caltex Theatre after 1947); the many Jack Davey Shows, and The Bob Dyer Show; the Colgate Palmolive variety extravaganzas, headed by Calling the Stars, The Youth Show and McCackie Mansion, which starred the outrageously funny Mo (Roy Rene). Fine drama programs produced in Sydney in the 1940s included The Library of the Air and Max Afford's serial Hagen's Circus. Among the comedy programs listed from this decade are the George Wallace Shows, and Mrs 'Obbs with its hilariously garbled language. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

'Not One Pound of Wheat Will Go': Words and Actions

8. ‘Not one pound of wheat will go’: Words and actions The Holstein Express was crewed by Indonesian seamen, but it sailed under a Liberian flag.1 Its Australian agents, Dalgety and Patricks, had been charged with the shipment of 600 dairy cows to Chile. In the week of 4 December 1978, the ship attempted to dock in Newcastle to load but was black banned by Australian workers. Union members would not assist with loading the cargoes. They simply refused. After discussion between the workers’ representatives and the agents, it was agreed that the ship could anchor outside the harbour in Stockton Bight and receive water and stores.2 It remained off Newcastle for two weeks.3 In stop-work meetings on 19 December 1978, the Sydney, Port Kembla, Port Adelaide and Victorian branches of the SUA all passed motions of support for the actions of their Newcastle branch.4 And shortly thereafter a white flag was raised by the owners in the form of a communiqué shown to the maritime unions that the ship would depart for New Zealand without cattle if it was able to refuel. The maritime unions allowed the ship to dock and refuel and it set off on 22 December 1978, apparently without cows and apparently for New Zealand. The company was in the middle of a goosestep that spanned the State. The next day, Don Henderson, secretary of the Firemen and Deckhands’ Union, was urgently advised that the ship was in fact at the southern NSW town of Eden loading hay and cattle.5 The union delegate at Eden was contacted and subsequently the local fishermen who had been hired to load the cattle stopped work.6 The ship’s crew and the vendors were forced to load the cattle themselves and the vessel departed for New Zealand on Sunday, 24 December 1978. -

Oral History: NFSA’S Hidden Collections by Graham Shirley Film Historian Graham Shirley Was the Speaker at AMOHG's September 2018 Meeting

Oral History: NFSA’s Hidden Collections By Graham Shirley Film historian Graham Shirley was the speaker at AMOHG's September 2018 meeting. Graham is arguably more familiar with the NFSA's oral history collection than anyone else – having recorded a great number, and used many more in his research. In his talk he noted that NFSA holds many oral history interviews with significant figures in the media industry – figures whose stories range from the silent film era to the present day. But while household names such as Jimmy Barnes and films like Picnic at Hanging Rock are featured and easy to find, there are hundreds of other interviews with industry figures who are less well-known, but whose memories and insights together tell the story of the Australian media industry, and how the rest of the NFSA's audiovisual collection – Australia's history on screen and in sound – came to be made. Profiling Oral History at NFSA Since the advent of the new NFSA website – ‘new’ as of several years ago - the NFSA’s oral history holdings have been profiled in ways unimaginable even five years ago. Much of this has been thanks to NFSA production teams who have collaborated with text, audio clips, video clips, photos and graphics for NFSA online exhibitions – for instance, those dealing with such well-known feature films as Picnic at Hanging Rock, Priscilla Queen of the Desert, Storm Boy, Muriel’s Wedding, Strictly Ballroom, and such household names as Graham Kennedy, the singers Jimmy Barnes and Tex Perkins, the actors Damon Herriman and Chris Haywood, and TV journalists including Barrie Cassidy, Jeff McMullen, Leigh Sales and Lisa Wilkinson. -

Bob Ellis at 70 PROFILE from the Bank to the Birdcage

20 12 HONIWeek Eleven October 17 SOIT Senate Results: Writing, women, From the Bank What Senator Pat and wowsers: to the Birdcage: means for you Bob Ellis at 70 Sydney’s drag kings CAMPUS 4 PROFILE 11 FEATURE 12 Contents This Week The Third Drawer SRC Pages 8 Sex, Messages, Reception. 19 Mason McCann roadtests the iPhone 5 The Back Page 23 Presenting the Honi Laureates Spooky Soit for 2012 10 Mariana Podesta-Diverio looks on the bright side of death Editor in Chief: Rosie Marks-Smith Editors: James Alexander, Hannah Bruce, Bebe D’Souza, 11 Profile: Bob Ellis Paul Ellis, Jack Gow, Michael Koziol, James O’Doherty, Michael Koziol talks to one of his Kira Spucys-Tahar, Richard Withers, Connie Ye heroes, Bob Ellis Reporters: Michael Coutts, Fabian Di Lizia, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Brad Mariano, Virat Nehru, Drag Kings Sean O’Grady, Andrew Passarello, Justin Pen, 12 Lucy Watson walks the streets of Hannah Ryan, Lane Sainty, Lucy Watson, Dan Zwi Newtown to teach us about drag Contributors: Rebecca Allen, Chiarra Dee, John Gooding, kings John Harding-Easson, Joseph Istiphan, Stephanie Langridge, 11 Mason McCann, Mariana Podesta-Diverio, Ben Winsor Culture Vulture 3 Spam 14 Crossword: Paps Dr Phil wrote us a letter! Well, sort of. Where has the real Slim Shady gone? Cover: Angela ‘panz’ Padovan of Panz Photography Asks John Gooding Advertising: Amanda LeMay & Jessica Henderson [email protected] Campus 16 Tech & Online 4 Connie Ye teaches us how to dance Justin Pen runs us through social your PhD media in modern Aussie politics HONISOIT.COM News Review Action-Reaction Disclaimer: 6 17 Honi Soit is published by the Students’ Representative Council, University of Sydney, Level 1 Why are Sydney buses exploding? An open letter to the Australian Rugby Wentworth Building, City Road, University of Sydney, NSW, 2006. -

Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012

Patrick Stevedores Operations No. 2 Patrick Stevedores Port Botany Container Terminal Project Section 75W Modification Application December 2012 Table of contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The proponent ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 The site ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Project context ................................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Document structure ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Project description ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Key aspects of the project ............................................................................................... 6 2.2 Demolition, enabling and construction works ................................................................. 10 2.3 Operation ...................................................................................................................... 12 2.4 Construction workforce and working hours.................................................................... -

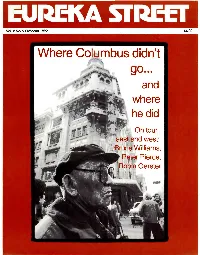

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

With Fond Regards

With Fond Regards PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by ELIZABETH RIDDELL ith Fond Regards W holds many- secrets. Some are exposed, others remain inviolate. The letters which comprise this intimate book allow us passage into a private world, a world of love letters in locked drawers and postmarks from afar. Edited by noted writer Elizabeth Riddell, and drawn exclusively from the National Library's Manuscript collection, With Fond Regards includes letters from famous, as well as ordinary, Australians. Some letters are sad, others inspiring, many are humorous—but all provide a unique and intimate insight into Australia's past. WITH FOND REGARDS PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by Elizabeth Riddell Compiled by Yvonne Cramer National Library of Australia Canberra 1995 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1995 Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publishers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry With fond regards: private lives through letters. ISBN 0 642 10656 8. 1. Australian letters. 2. Australia—Social conditions—1788-1900. 3. Australia—Social conditions—20th century. 4. Australia—Social life and customs—1788-1900. 5. Australia—Social life and customs— 20th century. I. Riddell, Elizabeth. II. Cramer, Yvonne. III. National Library of Australia. A826.008 Designer: Andrew Rankine Editor: Susan -

History Sydney Film Festival

HISTORY OF THE SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL 1954 - 1983 PAULINE WEBBER MASTER of ARTS FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 2005 For John and David ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank David Donaldson, Valwyn Wishart, John Baxter, Dorothy Shoemark, Tony Buckley, David Stratton and many others involved in the SFF during its formative years who gave generously of their time and knowledge during the preparation of this thesis. I am especially grateful to Trish McPherson, who entrusted me with the SFF memorabilia of her late husband, Ian McPherson. Thanks also to my supervisor, Professor Elizabeth Jacka, for her enthusiasm and support, and to Associate Professor Paul Ashton and Raya Massie who undertook to read the final draft and who offered invaluable advice. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Abbreviations i Sydney Film Festival: A Chronology 1954-1983 ii Abstract vi Introduction 1 An International Context; A Local Context Chapter One Art Form of a Generation: The Early Years 1954-1961 18 Reinventing Australia: 1946-1954; Connections and Divisions; Olinda 1952; From Concept to Reality; The First Festival; The Festival Takes Shape; Is it Here? Does it Look like Arriving?; Here to Stay; From Crisis to Cohesion Chapter Two Expansion and Consolidation: 1962-1975 57 Coming of Age; The Times They Are A-Changin’: 1962-1967; The Proliferation of Unacceptable Thoughts; Communal Rapture: The Start of the Stratton Era; The Anxious Years: 1968-1972; Throwing Down the Gauntlet; Going Global; The Festival at the Top of its Form; The Best and the Most Interesting; A Rising Clamour to be Seen and Heard Chapter Three Beguiling Times: The SFF and Australian Cinema 121 The Old and the New; The Film Buffs, the Festival People, the Trendies, the Underground; The Short Film Awards; A Thrilling New Wave: The Film Revival and After Chapter Four Change and New Directions: 1976-1983 149 A Lean Operation; Some of the People, Some of the Time; Backing Winners; Old Problems, New pressures; A Sort of Terrible Regression; The Last of the Stratton Years; 1983; 1984: Brave New World.