'Not One Pound of Wheat Will Go': Words and Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Z432 Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia, Federal Office Deposit

Z432 Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia, Federal Office deposit 6 Download list Amended July 2008 _______________________________________________________________ ANU ARCHIVES PROGRAM Telephone: +61 2 6125 2219 Noel Butlin Archives Centre Facsimile: +61 2 6125 0140 Email: [email protected] Incorporating the ANU Archives of Business & Labour Web: www.archives.anu.edu.au and the National AIDS Archive Collection WATERSIDE WORKERS FEDERATION Deposit No. Z432: Federal Office SITE LIST Receipt Dates Quantity Location 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel (D1-D5) Stack 294-295 5 May 1992 12 cartons (D6-14) Stack 294-295 27 May 1992 9 cartons & 1 archives box (4-13) Stack 294-295 11 Nov 1992 69 cartons & 1 parcel (14-78) Stack 294-295 21 Dec 1992 2 cartons (80-81- No 79) Stack 294-295 18 May 1993 18 cartons Stack 294-295 13 Jul 1994 2 parcels Stack 294-295 13 Jun/23 Dec 1996 1 bundle (82-86) Stack 294-295 Notes: 31 Mar 1992 5 cartons and 1 parcel of donated ACTU material – circulars and Executive minutes (cartons D1 to D5) 5 May 1992 12 cartons containing donated material – newspaper clippings and ACTU Bulletins and Newsletters (cartons numbered D6 to D14) and copies of Port News in cartons 1-3 (Boxes 1-3) 27 May 1992 9 cartons and 1 archives box containing miscellaneous material, rules, instruction booklets, published histories, circulars and records of N. Docker. Records of CH Fitzgibbon were also sent, but these were removed to his personal collection at P101 (remaining cartons numbered Boxes 4-13) 11 Nov 1992 65 cartons and 1 parcel. -

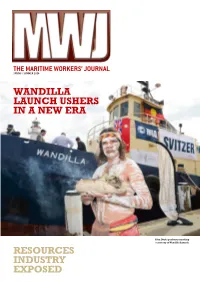

Wandilla Launch Ushers in a New Era Resources

THE MARITIME WORKERS’ JOURNAL SPRING / SUMMER 2014 WANDILLA LAUNCH USHERS IN A NEW ERA Glen Doyle performs smoking ceremony at Wandilla Launch. RESOURCES INDUSTRY EXPOSED p00_Cover.indd 1 19/11/13 9:07 AM CONTENTS 6 - 13 National Council: A meeting of minds 14 & 15 Chevron Campaign: BIS Shrapnel report shows resource industry loose with the truth 22 & 23 Vale Jimmy Tannock: Remembering retired National Deputy Secretary 35 Wandilla Launch: Tugboat signals beginning of new training initiative 41 Credit Union: MMPCU relocates as part of expansion 42 Financial Reports: MUA Concise Financial Report 2013 44 Dispute: Egyptian seafarers have a win in Kembla EDITOR IN CHIEF Paddy Crumlin COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Jonathan Tasini EDITORIAL TEAM Ashleigh Telford Greig Kelbie DESIGN Magnesium Media PRINTER Printcraft Maritime Workers’ Journal 365-375 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Contact: 9267 - 9134 Fax: 9261 - 3481 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.mua.org.au MWJ reserves the right at all times to edit and/or reduce any articles or letters to be published. Publication No: 1235 MUA members out in force to celebrate World Maritime Day at the For all story ideas, letters, obituaries please email Australian National Maritime Museum on Darling Harbour. [email protected] LOGGING ON LOGGING ON world economy down the toilet. The company negotiated an EBA without and Port of Convenience campaigns are Who knows really, because the Libs never telling its workforce what it was up to. illustrative of the capacity of international LOGGING had to say anything in opposition? The little Patrick, then, compounded this moral lapse maritime workers to effectively network in time Abbott has been in office doesn’t look by using a type of guerrilla management pursuing justice and accountability in the promising, though. -

AWB Scandal Timeline

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright MEDIATING JUSTICE INVESTIGATING THE FRAMING OF THE 2006 COLE INQUIRY Nonée Philomena Walsh Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a Master of Arts (Research) within the Department of Media and Communications, School of Letters, Art, and Media, The University of Sydney 2015 © Nonée Walsh CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Mediating justice: Investigating the framing of the 2006 Cole Inquiry, submitted to fulfil the conditions of a Master of Arts (Research), is the result of my own original research, except where otherwise acknowledged, and that this work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award. -

The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010 Patching, Roger Award date: 2014 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS The Private Lives of Australian Cricket Stars: a Study of Newspaper Coverage 1945- 2010 Patching, Roger Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: Bond University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Australia and Indonesia Current Problems, Future Prospects Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19

Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie Lowy Institute Paper 19 Australia and Indonesia CURRENT PROBLEMS, FUTURE PROSPECTS Jamie Mackie First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2007 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 2028 Australia www.longmedia.com.au [email protected] Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2007 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Jamie Mackie was one of the first wave of Australians of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, to work in Indonesia during the 1950s. He was employed mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the as an economist in the State Planning Bureau under copyright owner. the auspices of the Colombo Plan. Since then he has been involved in teaching and learning about Indonesia Cover design by Holy Cow! Design & Advertising at the University of Melbourne, the Monash Centre of Printed and bound in Australia Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Southeast Asian Studies, and the ANU’s Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. After retiring in 1989 he National Library of Australia became Professor Emeritus and a Visiting Fellow in the Cataloguing-in-Publication data Indonesia Project at ANU. He was also Visiting Lecturer in the Melbourne Business School from 1996-2000. His Mackie, J. A. C. (James Austin Copland), 1924- . publications include Konfrontasi: the Indonesia-Malaysia Australia and Indonesia : current problems, future prospects. -

Connie Healy Recollections of the 'Black Armada' in Brisbane

Connie Healy Recollections of the 'Black Armada' in Brisbane Since Boxing Day 2004, the attention of all Australians has been focussed on countries in Asia, particularly Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India. These countries were the worst affected by the devastating tsunami which struck their coastlines and other areas in the region such as Thailand, the Maldives and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Australians have been generous in their aid to assist those who survived, to help rebuild their devastated countries and their lives. This is the second time Australians have come to the forefront in assisting the Indonesian people. Back in the 1940s Australian trade unionists were the first to respond to an appeal from Indonesian Trade Unions. This appeal was directed to the 'democratic and peaceful peoples everywhere, and especially to the working class in all countries of the world, to boycott all that is Dutch in all harbours, stores, roadways and other places throughout the world in the event of the outbreak of warfare in Indonesia'.1 The boycott of Dutch shipping in Australia, colourfully described by journalist Rupert Lockwood as the 'Black Armada', was instrumental in preventing the return of Dutch shipping for the re-occupation of the Indies and the re-establishment of Dutch rule. It thus made way for the foundation of the Indonesian Republic. The embargo began in Brisbane and held up 559 vessels.2 The War Years: Our Indonesian Friends Prowito, Asir and Slamet In the large, rambling house on the top of the hill in a Brisbane suburb, we welcomed many visitors during the war years. -

2009 Annual Report 25 Years of Linking Australian Workers with the World Executive Officer’S Report

Union Aid Abroad APHEDA The overseas humanitarian aid agency of the ACTU 2009 Annual Report 25 years of linking Australian workers with the world Executive Officer’s Report Union Aid Abroad – APHEDA was established in 1984 by the ACTU under the name APHEDA (Australian People for Union Aid Abroad – APHEDA Health, Education and Development Abroad) as the Australian union movement’s celebrates 25 years overseas aid arm. We assist projects in South East Asia, the of international solidarity. Pacific, the Middle East and southern Africa, working through local partner organisations and unions to deliver training in vocational skills, health and workers’ rights so women and men may commitment to assisting for workers, especially for have decent work that provides other workers in greater women workers, for a living wage, reasonable need. Their generous disabled youth and for conditions and a safe support is a tribute to their trafficked women. workplace. Our international program seeks to empower belief in justice and a fair go women and men in developing for all. Thanks to donors and countries so they and their partners families might live with their Decent Work essential None of this training is human rights respected, both to overcome poverty possible, of course, without in their workplace and in their society. The ILO, the global union two very special groups of As Union Aid Abroad – movement and the ACTU people – our donors and OUR MISSION APHEDA celebrates 25 all advocate Decent Work our partners. Without the As the ACTU’s humanitarian aid agency, Union Aid Abroad years of international as essential to overcoming generous and growing – APHEDA expresses the solidarity on behalf of the poverty. -

Downloaded From

N. Bootsma The discovery of Indonesia; Western (non-Dutch) historiography on the decolonization of Indonesia In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 151 (1995), no: 1, Leiden, 1-22 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 12:20:47AM via free access N. BOOTSMA The Discovery of Indonesia Western (non-Dutch) Historiography on the Decolonization of Indonesia 'Independence from the Netherlands' was the name of a conference organized by the VGTE (Society for Twentieth-Century History) in The Hague on 19 November 1993. This name is open to two different inter- pretations. Firstly, it echoes a Dutch Communist Party slogan that was widely popularized between the two World Wars ('Indies independence from the Netherlands now'), which summarized the party's standpoint on the status of the then Dutch East Indies in rather a provocative way. Taken in this sense, the name should be viewed as a programme inviting reflec- tion, half a century after its implementation, on how precisely this former communist programme was realized. Thus interpreted, the name would require a revised review of the decolonization of Indonesia. However, the name may also allude to a publicly established fact, referring to a point in time at which the colonial ties had already been severed, or in other words, to Indonesia as an independent state. If the name is taken in this sense, a number of possible subjects for historical reflection present themselves. This essay is intended to explore the reactions of Western, non-Dutch, historiography to the foundation of the Republik Indonesia and the events leading up to and following it. -

Royal Commissions Amendment Bill 2006

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library BILLS DIGEST Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 7 June 2006, no. 149, 2005–06, ISSN 1328-8091 Royal Commissions Amendment Bill 2006 Sue Harris Rimmer Law and Bills Digest Section Contents Purpose.............................................................. 2 Background........................................................... 2 Legal Professional Privilege ........................................... 2 The Cole Inquiry.................................................... 4 The Federal Court finding ............................................. 5 ALP policy position ................................................. 6 Main provisions........................................................ 7 Schedule 1 – Amendment of Royal Commissions Act 1902 ....................7 Concluding Comments.................................................. 10 Endnotes............................................................ 11 www.aph.gov.au/librarwww.aph.gov.au/library www.aph.gov.au/library 2 Royal Commissions Amendment Bill 2006 Royal Commissions Amendment Bill 2006 Date introduced: 25 May 2006 House: House of Representatives Portfolio: Prime Minister Commencement: Sections 1 to 3 commence on the day of Royal Assent. Schedule 1 commences the day after Royal Assent. Purpose This Bill is to amend the Royal Commissions Act 1902 (the Act) to clarify the operation of the Act in respect of claims of legal professional privilege (LPP). Amendments were requested by -

No. 336, August 12, 1983

WfJRIlERI ",16(;(/,1" 25¢ No. 336 .~:';~~: X_,523 12 August 1983 W\I Photo Washington, D.C., 27 November 1982-5,000 jubilant demonstrators charge up Capitol Hill after Labor/Black Mobilization stops Klan march, '!:lIif "~'%I&iiUi ~~v:s.:Ql!jI'i'W_"'_~,~ 8Dor,BI8CkS: on'l raw tor Rooseveltian coalition which flopped so shown in Washington, D.C. last No Malcolm X blasted the 1963 March Democrat in the White House. That's miserably at the polls after four years of vember 27 when 5,000 responded to the on Washington, calling it the "Farce on . all. This march isn't about jobs, nor Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale. It is call of the Spartacist-initiated Labor/ Washington." But he wasn't laughing as freedom, nor peace. And it's certainly this coalition which ties the working Black Mobilization and stopped the Ku he lashed out against M.L. King & Co. not about a new civil rights movement. class and oppressed minorities to its Klux Klan from marching in the who were sinking the black struggle in They aren't even making promises this sworn enemies through the treachery of nation's capital. This direct blow against the cesspool of the Democratic Party. time. "Still have a dream?" How about a the labor tops and black politicos. The growing racist terror was hailed by Malcolm X was burning mad because he job? A school lunch? A decent educa Democratic Party, which black people decent people everywhere who knew knew it was going to take a revolution to tion? These necessities of life are vote for in overwhelming percentages, is that if the Klan had been able to stage win black freedom in America. -

ANTI-COMMUNISM in TASMANIA in the LATE 1950S with SPECIAL REFERENCE to the HURSEY CASE

ANTI-COMMUNISM IN TASMANIA IN THE LATE 1950s WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE HURSEY CASE Peter D. Jones M.A. (Oxon.), Dip.Ed. (Oxon.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities December 1995 UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the Thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except when due acknowledgement is made in the text of the Thesis. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. SYNOPSIS. While the strength of the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) was concentrated in Victoria, Tasmania was also significant for several reasons : it was the electoral base of Senator George Cole, the DLP's leader in the Senate up to 1964; Hobart was the venue of the ALP Federal Conference when the Split occurred in 1955; and it was the only state with a Labor Government throughout the Menzies years. While the Anti-Communist Labour Party, later the DLP, contested all State and Federal elections after 1956, they failed to make significant inroads into the ALP vote, although Senator George Cole (first elected on the ALP ticket in 1949) was able to maintain his Senate seat until 1964 - largely because of the Tasmanian tradition of voting for personalities rather than ideologies. The DLP vote in both State and Federal elections failed to affect the overall results, except in the 1959 state election, when DLP preferences in Franklin gave an extra unexpected extra seat to the Liberal Party and resulted in a situation where two Independents held the balance of power. -

Decolonising Indonesia, Past and Present

Downloaded from <arielheryanto.wordpress.com> Asian Studies Review ISSN: 1035-7823 (Print) 1467-8403 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/casr20 Decolonising Indonesia, Past and Present Ariel Heryanto To cite this article: Ariel Heryanto (2018) Decolonising Indonesia, Past and Present, Asian Studies Review, 42:4, 607-625, DOI: 10.1080/10357823.2018.1516733 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1516733 Published online: 18 Sep 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 295 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=casr20 Downloaded from <arielheryanto.wordpress.com> ASIAN STUDIES REVIEW 2018, VOL. 42, NO. 4, 607–625 https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1516733 Decolonising Indonesia, Past and Present Ariel Heryanto Monash University ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In the pursuit of an “authentically Indonesian” nation-state, for Cold War; colonial; ethno- decades Indonesians have denied the civil rights of fellow citizens nationalism; identity; for allegedly being less authentically Indonesian. A key to the Indonesia; Indonesia Calling; longstanding efficacy of such exclusionary ethno-nationalism is Left; trans-national the failure to recognise the trans-national solidarity that helped give birth to independent Indonesia. Such solidarity is best illu- strated in the extraordinary case of the making in Australia of a documentary film, Indonesia Calling (1946). A starting point of this article is the proposition that Indonesia’s cultural politics of the past and its future is never free from a protracted battle over what the nation is allowed, or willing, or able to forget and remember from its past.