147-154 Islam and Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Stock Transfer Service Inc. Page No

Stock Transfer Service Inc. Page No. 1 FILINVEST DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Stockholder MasterList As of 03/09/2018 Count Name Holdings ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 A.L. GOTIANUN, INC. 7,587,823,502 2 AACTC - CEBU FAO PACITA ONG 6,166 3 AACTC AS TRUSTEE FOR TA 94-007 1,233 4 AACTC FAO TA #96 003 616 5 AASMC FAO NONATO MENDOZA 1,233 6 ANGEL D. ABABAO 30,830 7 NOREEN ABABAO 6,166 8 TERESITA B. ABABAO 14,798 9 TERESITA B. ABABAO 22,197 10 TERESITA T. ABABAO 29,596 11 ABACUS SECURITIES CORP. 3,100 12 MARLON G. ABAD 1,973 13 SALVADOR S. ABAD SANTOS 739 14 ABAD JOSE ROMAN 2,466 15 MA. JASMIN ABAD 4,932 16 FLOR A. ABADIER 246 17 DBP TSD FAO CESAR ABAIGAR (CATBALOGAN) 986 18 DBP TSD FAO ROSARIO ABAIGAR (CATBALOGAN) 1,479 19 TEODORO U. ABALOS 7,399 20 MARIA CHRISTINA R. ABANILLA 1,233 21 YOLANDA P. ABANTO 7,399 22 DBP TSD FAO MAE ABARQUEZ (MALAYBALAY) 1,973 23 MA. GRACIA DE GUZMAN ABAS 493 24 CHONA D. ABAYA 986 25 DBP TSD FAO EVELYN ABBACAN (TABUK) 493 26 GERARDO T. ABELEDA 493 27 GERARDO T.ANTONIO A. ABELEDA 493 28 EDWARD C ABELLERA 493 29 EDWARD C. ABELLERA 493 30 SAMUEL O. ABELLERA 2,466 31 ROSALINDA G. ABETO 1,233 32 ROSALYN B. ABIERA 5,919 33 RUTH T. ABITONG 2,466 34 MIGUELA A. ABOGADIE 493 35 ABOITIZ & CO., INC. 197,312 36 ABOITIZ EQUITY VENTURES, INC. 160,316 37 ERICO &/OR FELICIDAD ABORDO 493 38 LUIS A. -

A Deleuzian Reading of the EDSA Revolutions and the Possibility of Becoming-Revolutionary Today

Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 14(1) 2014, pp. 59-74 A Deleuzian Reading of the EDSA Revolutions and the Possibility of Becoming-Revolutionary Today Raniel SM. Reyes The Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents a Deleuzian re-thinking of the three EDSA Revolutions in the Philippines. Its frame is limited to contemporary and critical studies found in books, journals, and newspapers. Initially, I elucidate the nature of 1986 EDSA I Revolution, to be followed by an articulation of the concepts of assemblage and difference for a re-configuration of the 1986 revolution. I highlight and explain how the Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA) transfigured into an arena of collective and dynamic action of various assemblagic relations. The rhizomic interaction of heterogeneous forces in the said highway undeniably exterminated the privileging of numerous traditional representations in the Philippine society. Furthermore, I explain the transition from the EDSA I revolution going to the EDSA II with a principal thrust on the principle of the eternal return as the return of the different, and the paradoxical ever-recurrence of political tyranny. Lastly, I explicate the narrative on how the Filipino assemblage is always caught in the web of ressentiment and identity, based from the EDSA I, II, and III. Due to these degenerate consequences, this essay recommends the conception of a new brand of revolution that is critical of molar and fascist political representations―the possibility of becoming-revolutionary today. Keywords: Deleuze, EDSA revolution, despotism, assemblage, difference, eternal return, becoming- revolutionary A revolution is something of the nature of a process, a change that makes it impossible to go back to the same point . -

The Conflict-Sensitive Journalism Teaching Guide

LOREM IPSUM SIT AMET THE CONFLICT-SENSITIVE JOURNALISM TEACHING GUIDE PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE FIRST EDITION 1 Copyright © 2018 by forumZFD (Forum Ziviler Friedensdienst/ Forum Civil Peace Service), Commission on Higher Education – Regional Office XI, PECOJON and the Media Educators of Mindanao , Inc. This publication can be reproduced by any process so long as it is used in line with peace education and campaign, activities and projects, as well as the advancement of conflict-sensitive journalism. However, the publishers shall be duly credited. First edition, 2018 The Conflict-Sensitive Journalism Teaching Guide: Philosophy and Practice EDITORS AND AUTHORS Ed Karlon Rama, Katja Gürten CO-AUTHORS Marianne P. Afrondoza, Christine Faith M. Avila, Lorenzo I. Balili Jr., Venus B. Betita, Helen Fornelos-Fungo, Dinah C. Hernandez, Derf Hanzel Maiz, Mark Roel B. Narreto, Rowena Nuera, Virgilind V. Palarca, Rosa Maria T. Pineda, Joy R. Risonar, Daniel Fritz Silvallana TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Frances Jan Lozano, Gabrielle Aziza J. Sagaral, Sophie Schellens LANGUAGE EDITOR Bernard Julian A. Patiño LAYOUT Karla Degrano forumZFD (Forum Ziviler Friedensdienst/Forum Civil Peace Service) B305-307 Plaza de Luisa Complex R. Magsaysay Avenue, 8000 Davao City Mindanao/Philippines PECOJON - Peace and Conflict Journalism Network Philippines Incorporated 10-A Alo Compound, Elizabeth Pond Extension, Kamputhaw, Cebu City 6000 Philippines Media Educators of Mindanao, Inc. (MEM) https://www.facebook.com/mediaeducatorsofmindanao/ Commission on Higher Education (CHED) -

PHILIPPINES (FINAL) (Revised 15 June 2011)

Roadmapping Capacity Building Needs in Consumer Protection in ASEAN ASEAN AUSTRALIA DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION PROGRAM PHASE II (AADCP II) ROADMAPPING CAPACITY BUILDING NEEDS IN CONSUMER PROTECTION IN ASEAN Consumers International COUNTRY REPORT: PHILIPPINES (FINAL) (Revised 15 June 2011) ―The views expressed in this report are those of the author/s, and not necessarily reflect the views of the ASEAN Secretariat and/or the Australian Government. The report has been prepared solely for use of the ASEAN Secretariat and should not be used by any other party or for other than its intended purpose.‖ Country Report – Philippines (Final) i ABSTRACT The Philippines is one of the 10 ASEAN Member States (AMS) that have a general consumer protection law. Called the Consumer Act of the Philippines or Republic Act No. 7394, it has comprehensive legal provisions for consumer protection. The Act has improved consumer protection in the Philippines. It has been translated into a number of programs and projects, which increased awareness on consumer rights and advanced consumer welfare. The integration of consumer education in secondary school curriculum and the establishment of consumer redress mechanisms by the Department of Trade and Industry in all its offices are some of the laudable efforts of the Philippine government on consumer protection. Much still needs to be done though. One of the fundamental rights of consumers - that is the right to satisfaction of basic needs - has yet to be fulfilled for Juan dela Cruz1 and over 90 million other Filipinos. This report aims to walk through readers with the formal and operational contexts of consumer protection in the Philippines. -

In This Issue of KRITIKE: an Online Journal of Philosophy

KRITIKE VOLUME FOUR NUMBER TWO (DECEMBER 2010) i-v Editorial In this Issue of KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy Paolo A. Bolaños he Editorial Board of KRITIKE: An Online Journal of Philosophy is happy to release the journal’s eighth edition, marking the culmination of T the year 2010. The essays in this edition tackle, in varying degrees but all of sterling quality, issues on language and hermeneutics, society and the problem of commodification, mediated psychopathy, education, postcolonial discourse, political resistance, the reception of critical theory, and also on more philological treatments of the works of Plato, Nietzsche, and Kant. The interdisciplinary character of these essays and the cross-pollination of theoretico-critical discourses demonstrated by them are not to be missed. The so called “linguistic turn” in Western philosophy has an indefinitely long and complex history. The phrase was itself coined by the Austrian philosopher and member of the Vienna Circle, Gustav Bergmann, during the early 20th Century, to refer to the philosophical study of language, understood by Analytic philosophers as propositional logic. This philosophical preoccupation with language, however, cuts through the Continental-Analytic divide. As a matter of fact, Plato already mentioned the significance of speech in philosophy in the Timaeus and also took issue with the normative character of names in the Cratylus. A similar concern about language reemerges during the 18th Century via the works of Johann Georg-Hamann, who analyzed the constitutive function of language in thought. This is followed through by the Hermeneutical tradition, championed by Friedrich Daniel Schleiermacher. The philosophical study of language is carried over by more contemporary hermeneutical philosophers, especially Paul Ricoeur. -

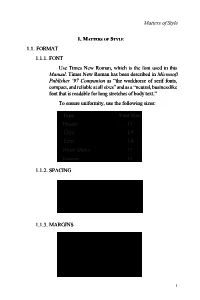

Title 14 Text 14 Blockq Uote 12

Matters of Style 1. MATTERS OF STYLE 1.1. FORMAT 1.1.1. FONT Use Times New Roman, which is the font used in this Manual . Times New Roman has been described in Microsoft Publisher ’97 Companionn as “the workhorse of serif fonts, compact, and reliable at all sizes” and as a “neutral, businesslike font that is readable for long stretches of body text.” To ensure uniformity, use the following sizes: Type FontS ize Header 12 Title 14 Text 14 BlockQ uote 12 Footnote 10 1.1.2. SPACING TTyyppe SSppaaccee TTeexxtt 11..55 BBlloocckQQ uuootteess 11 BBeettwweeeenpp aarraaggrraapphhss 33 1.1.3. MARGINS PPoossiittiioon SSiizzee LLeefftt 11..55”” RRiigghhtt 11”” TToopp 11”” BBoottttoomm 11”” 1 Manual of Judicial Writing 1.2. TITLE PPAGE The essential parts of a standard title page of a Supreme Court decision or signed resolution are as follows: 1.2.1. TITLE PAGE HEADER The title page header shows the seal of the Supreme Court in the first line, the name Republic of thee Philippines in the second line, the name Supreme Court in the third line, the place where the Court held session in the fourth line, and, after three spaces from the fourth line, the words En Banc,, First Divivisision,, Second Division, or Third Division.. 1.2.2. CASE TITLE The title of the case consists of the names of the parties and their appropriate designations, such as complainant, appellant, appellee,, petitititioner , and respondent .. Examples: People of the Philippines, Appellee, -versus- Juan de la Cruz, Appellant. x - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x Lauro C. Bautista, Complainant, -versus- Judge Juana de la Cruz, Municipal Circuit Trial Court, San Pablo-San Pedro, Isabela, Respondent. -

Download File

1 2 Editorial Board Fermin R. De Leon Jr, PhD, MNSA President, NDCP Ernesto R. Aradanas, MNSA Executive Vice President ________________________________________ RESEARCH & SPECIAL STUDIES DIVISION EDITORIAL TEAM Ananda Devi Domingo-Almase, Clarence Anthony P. Dugenia, Manmar C. Francisco, Segfrey D. Gonzales, Gee Lyn M. Magante, Ma. Charisse E. Gaud, Patricia Ann V. Ingeniero, Joy R. Jimena, Christian O. Vicedo, Cesar Jerome P. Azarcon, and Miriam G. Albao Copyright 2013 by NDCP This volume is a special anniversary edition of the National Security Review and is published by the Research and Special Studies Division (RSSD), National Defense College of the Philippines. The papers compiled herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and policies of their affiliated governments and institutions. Comments and suggestions are welcome and may be sent to RSSD, NDCP Camp Aguinaldo, Quezon City, with telephone number +63-2-912-9125. 3 Editorial Note 1 EDITORIAL NOTE rom idealism after the First World War to realization of real and persistent conflicts in the Second World War and beyond, studies on security have Fbeen highly influenced by the lens and language of realism. As a powerful theoretical tradition in International Relations and its subfield of Security Studies, realism provides systematic explanation and understanding of the security environment in which threats are real. It has brought back security theorizing to its senses, by making the discourse on realpolitik, armed conflicts, and state survival in an anarchic international community even more vibrant and vigilant. In the absence of a central governing authority in the international system, security has been construed by sovereign states along the lines of their own national security interests and strategic goals. -

Environmental Dispatches

1 ENVIRONMENTAL DISPATCHES: REFLECTIONS ON CHALLENGES, INNOVATION AND RESILIENCE ENVIRONMENTAL IN ASIA-PACIFIC DISPATCHES: Refl ections on Challenges, Innovation and Resilience in Asia-Pacifi c Copyright © 2015, United Nations Environment Programme United Nations Avenue, Gigiri PO Box 30552, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya http://www.unep.org/ http://www.apfedshowcase.net/ Publication: Environmental Dispatches: Reflections on Challenges, Innovation and Resilience in Asia Pacific Job Number: RSO/1902/BA This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or nonprofit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. ENVIRONMENTAL Application for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, DCPI, UNEP 2 PO Box 30552, Nairobi, 00100, Kenya. 3 ENVIRONMENTAL DISPATCHES: ENVIRONMENTAL DISPATCHES: DISPATCHES: REFLECTIONS Disclaimer REFLECTIONS ON CHALLENGES, The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ON CHALLENGES, INNOVATION United Nations Environment Programme. INNOVATION AND RESILIENCE Refl ections on Challenges, Innovation AND RESILIENCE IN ASIA-PACIFIC IN ASIA-PACIFIC While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct and properly referenced, UNEP does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and Resilience in Asia-Pacifi c and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

Apr.-+Jun+2011.Pdf

G/F Nurses’ Home, Philippine General Hospital Compound Taft Avenue, Manila 1000 Philippines Tel: (02) 554-8400 local 3061, (02) 567-4272 Newsletter Telefax: (02) 536-2874 Website: www.pghmedfoundation.com Email: [email protected] Volume II, Issue 2 April-June2011 A quarterly publication of PGHMFI PGHMFI HOLDS 8th ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING PGHMFI held its 8 th annual meeting last March 25, 2011 at the Alvior Hall, UP Col- lege of Medicine. Dr. Gregorio T. Alvior, Jr., foundation president took the opportunity to report on the gains and accomplishments for the year 2010; where it continued to conduct its regu- lar programs such as the pro- vision of medicines and labo- ratory procedures for the needy patients of the hospital through the Charity Patients Medical Fund (CPMF). PGHMFI New Members (L-R) Mr. John Pallasigue – a businessman/art collector, Dr. Gerardo It succeeded in addressing the Legaspi – PGH-DPPS Chairman, Dr. Maria Cristina Estrada –PGH Dept. of Dentistry Chairman, Ms. request of the Dept. of OB- Marina Laroya – Businesswoman/Civic Leader, Mrs. Adelaida E. Lopez – Civic Leader and wife of the Gyn for the much needed former Ambassador and UP President Salvador Lopez, Dr. Ester Saguil – PGH-DOPS Chairman,, facility to serve the medical Mrs. Helen Massab – Businesswoman/PR Consultant, and Dr. Gregorio MS Azores – PGH needs of Filipino women, Coordinator for Special Projects being inducted by PGH Director Dr. Jose C. Gonzales particularly for normal deliv- ery cases which it has not new members and delivered been able to sufficiently sat- the closing remarks where he UPCM Class ‘ 60 Donates to PGHMFI isfy because of the limited said that he aims his incum- hospital facility. -

From the Chancellor's Desk

Volume XVIII Issue No. 70 1 April–June 2016 Volume XVIII Issue No. 70 ISSN 2244-5862 From the Chancellor’s Desk It was business as usual for PHILJA in the months of April, May and June 2016. Various regular programs such as the respective Orientation Seminar-Workshops for Newly Appointed Judges (75th and 76th), for Newly Appointed Clerks of Court (31st), and for Newly Appointed Sheriffs and Process Servers (8th) were successively held, along with an Orientation Seminar for Judges and Court Decongestion Officers (2 batches). Two Pre-Judicature Programs (37th and 38th), a Career Development Program for Court Legal Researchers of the Visayas, a Judicial Career Enhancement Program for First Level Court Judges of Region XI, and the Career Enhancement Programs for Court Judges listen as a COMELEC representative explains the features of the Vote Librarians and Regional Trial Court Sheriffs of the NCJR (Batch Counting Machine (VCM) during one of the four seminars on election laws 4) were likewise conducted during this quarter. for judges conducted by the Academy in April at the PHILJA Training Center, Tagaytay City. The Training Seminar on the 2016 Revised Rules of Civil Procedure for Small Claims Cases for the First Level Court made Legal Researchers, Social Workers and Law Enforcement up a good part of our special focus programs at this time as we Investigators Handling Trafficking in Persons Cases (ACET-TIP) carried out six such activities for Judges and their respective was launched in a well-attended affair which was graced by Chief Clerks of Court of Judicial Regions II, III, IX, XI, X and XII, and Justice Maria Lourdes P. -

Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers 2008

DIRECTORY of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers 2008 Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center Osaka, Japan Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers 2008 Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers was published by the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center 2-8-24 Chikko Minato-ku, Osaka 552-0021 Japan Copyright © Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center, 2008 Printed and bound by Takada Osaka, Japan All rights reserved. FOREWORD We launched the Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers in late 2007 to highlight the important role that organizations, institutes, and other entities that gather and disseminate information on human rights play or should play in the field of human rights. This Directory (with an online version) profiles the organizations, institutes, and other entities in the Asia-Pacific that perform the role of human rights centers in one way or the other. The numerous issues, programs, approaches and outputs they work on show the existence of resources that are useful for human rights protection, promotion and realization. This Directory provides a substantive list of the human rights centers in the Asia-Pacific. Yet, it certainly does not cover all the human rights centers existing in various parts of the region. It includes human rights centers that work at various levels – community, national, regional and international. We hope that this Directory helps focus attention to the importance of gathering and disseminating information on human rights as shown by the valuable work of the human rights centers. We hope also that this Directory opens more opportunities for people, particularly those in small communities, to make the human rights centers work for their needs and aspirations.