Eileen O'rourke & John A. Finn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Range Transportation Plan for Fish and Wildlife Service Lands In

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Long Range Transportation Plan for Fish and Wildlife Service Lands in Region 1 Final Draft September 2011 Long Range Transportation Plan for Fish and Wildlife Service Lands in Region 1 Primary Contact Jeff Holm Chief, R1 Branch of Transportation, Refuge Roads Coordinator, R1 & R8 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System 911 NE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97232 [email protected] 503/231-2161 Acknowledgements Mike Marxen, Chief, R1 Branch of Visitor Services and Communication Paul Hayduk, R1 Hatchery and Facility Operations Coordinator Roxanne Bash, Western Federal Lands, Federal Highway Administration Special Thanks Steve Suder, National Coordinator, Refuge Transportation Program, FWS Nathan Caldwell, National Alternative Transportation Coordinator, FWS Alex Schwartz, R1 Landscape Architect Kirk Lambert, R1 Asset Management Coordinator David Drescher, Chief, R1 Refuge Information Susan Law, Western Federal Lands, Federal Highway Administration Pete Field, Western Federal Lands, Federal Highway Administration Consultant Team Atkins Melissa Allen, AICP Steve Hoover, AICP Tina Brand Cover Photo: David Pitkin/USFWS U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service - Region 1 Long Range Transportation Plan for Fish and Wildlife Service Lands in Region 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................... .ES-1 Why was the Long Range Transportation Plan for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lands initiated? .... .ES-1 What are the Goals for this Long Range Transportation -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

(Icelandic-Breeding & Feral Populations) in Ireland

An assessment of the distribution range of Greylag (Icelandic-breeding & feral populations) in Ireland Helen Boland & Olivia Crowe Final report to the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency December 2008 Address for correspondence: BirdWatch Ireland, 1 Springmount, Newtownmountkennedy, Co. Wicklow. Phone: + 353 1 2819878 Fax: + 353 1 2819763 Email: [email protected] Table of contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 2 Methods......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Results........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Coverage................................................................................................................................................... 3 Distribution ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Site accounts............................................................................................................................................ -

Conservation Objectives Series National Parks and Wildlife Service

ISSN 2009-4086 National Parks and Wildlife Service Conservation Objectives Series Lough Forbes Complex SAC 001818 04 May 2016 Version 1 Page 1 of 18 National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 7 Ely Place, Dublin 2, Ireland. Web: www.npws.ie E-mail: [email protected] Citation: NPWS (2016) Conservation Objectives: Lough Forbes Complex SAC 001818. Version 1. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Series Editor: Rebecca Jeffrey ISSN 2009-4086 04 May 2016 Version 1 Page 2 of 18 Introduction The overall aim of the Habitats Directive is to maintain or restore the favourable conservation status of habitats and species of community interest. These habitats and species are listed in the Habitats and Birds Directives and Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas are designated to afford protection to the most vulnerable of them. These two designations are collectively known as the Natura 2000 network. European and national legislation places a collective obligation on Ireland and its citizens to maintain habitats and species in the Natura 2000 network at favourable conservation condition. The Government and its agencies are responsible for the implementation and enforcement of regulations that will ensure the ecological integrity of these sites. A site-specific conservation objective aims to define favourable conservation condition for a particular habitat or species at that site. The maintenance of habitats and species within Natura 2000 sites at favourable conservation condition will contribute to the overall maintenance of favourable conservation status of those habitats and species at a national level. -

Ecological-Economic Analysis of Wetlands: Science and Social Science Integration*

ECOLOGICAL-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF WETLANDS: SCIENCE AND SOCIAL SCIENCE INTEGRATION* R.K. Turner, CSERGE, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK and University College London. J.C.J.M. van den Bergh, Dept. of Spatial Economics, Free University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands A. Barendregt, Dept. of Environmental Sciences, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands E. Maltby, RHIER and Geography Department, Royal Holloway College, University of London. * The present paper and a more policy oriented twin paper were started in the context of the Global Wetlands Economics Network (GWEN). This network aims to promote multidisciplinary and international communication and collaboration between natural and social scientists that are involved in research on wetlands processes and management. It will contribute to the exchange of information and ideas about research methods and practical application of ecosystem valuation techniques, systems analysis tools and evaluation methods with particular reference to wetlands management. It is also meant to encompass both basic social science research work and user group oriented policy analysis. The network has had four meetings between February 1995 and November 1997 (in the UK, The Netherlands, Italy and Sweden). Abstract Wetlands provide many important services to human society, but are at the same time ecologically sensitive systems. This explains why in recent years much attention has been focused on sustainable management strategies for wetlands. Both natural and social sciences can jointly contribute to an increased understanding of relevant processes and problems associated with such strategies. Starting from this observation, the present paper considers the potential integration of insights and methods from natural or social sciences to better understand the interactions between economies and wetlands. -

Copyrighted Material

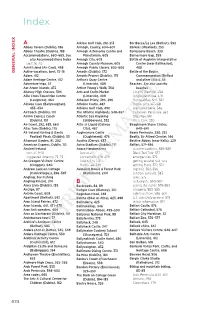

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard), -

Press Release Gormley Confirms End of Derogation Allowing Turf-Cutting

Press Release Gormley confirms end of derogation allowing turf-cutting on limited number of bogs Less than 5% of peatlands will be affected. The Minister for the Environment, Heritage & Local, John Gormley, T.D., following a Government decision, has confirmed that the derogation granted in 1999 to allow a continuation of non-commercial turf-cutting has ended for 31* raised bog Special Areas of Conservation (SACs). Further turf-cutting or associated drainage works on these sites cannot proceed without the express consent of the Minister. It is estimated that about 750 people have been harvesting turf from these bogs in recent years. Similar derogations will end for a further 24 SACs at the end of 2011 and for 75 Natural Heritage Areas at the end of 2013. In total, these sites make up less than 5% of peatlands in the State where turf-cutting is feasible. The remaining 95% of peatlands will be unaffected. Cutting on blanket bog Special Areas of Conservation which occur predominately on the western seaboard, will be allowed to continue under the restrictions introduced in 1999. These raised bogs contain rare and threatened natural habitat that is protected under National and European law. They are on sites that are designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) or Natural Heritage Areas (NHAs). Turf-cutting and associated drainage damage the bogs and the continuation of these activities is incompatible with their preservation. The Minister also announced that his Department will provide interim funding to address the immediate needs of those who have been relying on these bogs to source their fuel. -

Pollardstown Fen

BOGS OF IRELAND text 11/18/03 2:32 pm Page 27 Toghers were used as military bottlenecks by the native Irish against invading English armies in later centuries, particularly when they provided the only means of access to a settlement, castle or monastery. Trenches were dug across toghers or the toghers were broken up altogether as a method of stalling the enemy. i.e. it took Lord Mountjoy two years to cross the midland bogs into Ulster in pursuit of Hugh O’Neill after the battle of Kinsale in 1601 because he did not know the togher routes. 27 BOGS OF IRELAND text 11/18/03 2:32 pm Page 28 28 BOGS OF IRELAND text 11/18/03 2:32 pm Page 29 7 BOGS IN IRISH ECONOMY PAST: The bogs were the last wilderness to take shape in the Irish landscape in the wake of the Ice Age. During the first millennia little could be done to reclaim these barren wet deserts and replace them with fields as had been done with most of the forest wilderness in other parts of the world. This relationship between humans and bogs in Ireland changed for two reasons: 1. The increasing scarcity of wood as a domestic fuel. 2. An increasing population. Turf was found not to be an inferior fuel. It burnt low and evenly and there was little chance of burning splinters setting fire to the house, as with wood. The old Irish law text, "The Seanchas Mór" dates from the 7th & 8th centuries. It refers to "the ditch of a turf cutting" as among the seven ditches which are exempt from liability in the case of accidental drowning. -

Irish Rare Bird Report 2009 2009 Irish Rare Bird Report Introduction

Mark Carmody 2009 Cork. 15th November Bluethroat. Ballycotton, Co. Irish Rare Bird Report 2009 2009 Irish Rare Bird Report Introduction Although many of the best birds did not linger long, there were two species added to the Irish list in 2009, a Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum (Galway) in October and a long awaited Red-flanked Bluetail Tarsiger cyanurus (Cork) in November. A Red-billed Tropicbird Phaethon aethereus at sea in September came tantalisingly close to being added to the main list but the recorded location was just beyond the 30 kilometre inshore zone. Recorded for the second time, a Royal Tern Sterna maxima (Cork) in June was the first live record of the species which consequently moves onto the full Irish list, having previously been placed in Category D. In October, both Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura (Cork) and Common Nighthawk Chordeiles minor (Kerry) were recorded for the second time. The third Terek Sandpiper Xenus cinereus (Dublin) was found in July and the fourth Isabelline Shrike Lanius isabellinus (Mayo) in October. Rare subspecies recorded during the year included the second Balearic Woodchat Shrike Lanius senator badius (Wexford) in May. This report also includes details of the fourth Arctic Redpoll Carduelis hornemanni (Mayo) recorded in October 2008. For the second year in succession, the early months of the year were characterised by a large influx of Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis, although the numbers involved were considerably less than the exceptional influx of 2008. The end of the winter was marked by the occurrence in mid-February of a Great Spotted Cuckoo Clamator glandarius and an Ivory Gull Pagophila eburnea in early March, both in Cork. -

Ecological Surveying Techniques for Protected Flora and Fauna During the Planning of National Road Schemes NRA Ecological Survey Maciek 3/19/09 11:55 AM Page Ii

NRA Ecological Survey maciek 3/19/09 11:55 AM Page i Ecological Surveying Techniques for Protected Flora and Fauna during the Planning of National Road Schemes NRA Ecological Survey maciek 3/19/09 11:55 AM Page ii Ecological Surveying Techniques for Protected Flora and Fauna during the Planning of National Road Schemes ii NRA Ecological Survey maciek 3/19/09 11:55 AM Page iii CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Structure of the ‘Survey Guidelines’ .................................................... 2 Chapter 3 Survey considerations ........................................................................... 3 3.1 Recognising and dealing with key potential constraints/limitations 3 3.1.1 Seasonal constraints .................................................................... 3 3.1.2 Climatic conditions ...................................................................... 3 3.1.3 Inter-annual variation ................................................................. 3 3.1.4 Access limitations ........................................................................ 3 3.2 Survey effort ......................................................................................... 3 3.3 Survey standards ................................................................................... 5 3.4 Establishing baseline conditions .......................................................... 5 3.5 Monitoring ........................................................................................... -

BIODIVERSITY in IRELAND a Review of Habitats and Species

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY An Ghníomhaireacht um Chaomhnú Comhshaoil Ireland’s Environment BIODIVERSITY IN IRELAND A Review of Habitats and Species John Lucey and Yvonne Doris ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY PO Box 3000, Johnstown Castle Estate, Co. Wexford, Ireland. Telephone: +353 53 60600 Fax: +353 53 60699 Email: [email protected] Website: www.epa.ie July 2001 BIODIVERSITY IN IRELAND C ONTENTS LIST OF BOXES . iii LIST OF FIGURES . iv LIST OF TABLES . iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v INTRODUCTION . 1 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK . 2 HABITATS . 4 Forests and Woodland . 4 Hedgerows . 5 Fen and Bog . 6 Turloughs . 7 Freshwater Habitats . 8 Coastal and Marine Habitats . 8 SPECIES . 10 Flora (Plants) . 10 Fauna (Animals) . 15 DISCUSSION . 22 CONCLUSIONS . 29 POSTSCRIPT . 32 NOTES . 32 REFERENCES . 33 APPENDIX 1 . 38 PAGE II A REVIEW OF HABITATS & SPECIES L IST OF B OXES 1 IRISH GEOLOGICAL HERITAGE . 1 2 CONSERVATION OF NATURAL AND SEMI-NATURAL WOODLANDS . 4 3 BOGS . 6 4 TURLOUGHS . 7 5 COASTAL / MARINE HABITATS . 9 6 MAËRL COMMUNITIES . 9 7 LOWER PLANTS . 13 8 VASCULAR PLANTS . 14 9 KERRY SLUG . 15 10 FRESHWATER INVERTEBRATES . 16 11 MARSH FRITILLARY . 16 12 LAND SNAILS . 17 13 SOME RECENT INSECT AND MITE INTRODUCTIONS TO IRELAND . 17 14 FISHES . 18 15 AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES . 19 16A GREENLAND WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE . 19 16B BIRDS . 20 17 MAMMALS . 21 18 CETACEANS . 22 19 ANIMAL EXTINCTIONS AND INTRODUCTIONS DURING THE PAST MILLENNIUM . 23 20 OVERGRAZING . 24 21 GENETIC RESOURCES . 28 22 THREATS TO BIODIVERSITY . 29 23 CLIMATE CHANGE AND BIODIVERSITY . 30 PAGE III BIODIVERSITY IN IRELAND L IST OF F IGURES 1 FRAMEWORK FOR THE DESIGNATION OF NATURA 2000 SITES .