Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Background, Analysis, and Performance Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Finale Transposition Chart, by Makemusic User Forum Member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans

Finale Transposition Chart, by MakeMusic user forum member Motet (6/5/2016) Trans. Sounding Written Inter- Key Usage (Some Common Western Instruments) val Alter C Up 2 octaves Down 2 octaves -14 0 Glockenspiel D¯ Up min. 9th Down min. 9th -8 5 D¯ Piccolo C* Up octave Down octave -7 0 Piccolo, Celesta, Xylophone, Handbells B¯ Up min. 7th Down min. 7th -6 2 B¯ Piccolo Trumpet, Soprillo Sax A Up maj. 6th Down maj. 6th -5 -3 A Piccolo Trumpet A¯ Up min. 6th Down min. 6th -5 4 A¯ Clarinet F Up perf. 4th Down perf. 4th -3 1 F Trumpet E Up maj. 3rd Down maj. 3rd -2 -4 E Trumpet E¯* Up min. 3rd Down min. 3rd -2 3 E¯ Clarinet, E¯ Flute, E¯ Trumpet, Soprano Cornet, Sopranino Sax D Up maj. 2nd Down maj. 2nd -1 -2 D Clarinet, D Trumpet D¯ Up min. 2nd Down min. 2nd -1 5 D¯ Flute C Unison Unison 0 0 Concert pitch, Horn in C alto B Down min. 2nd Up min. 2nd 1 -5 Horn in B (natural) alto, B Trumpet B¯* Down maj. 2nd Up maj. 2nd 1 2 B¯ Clarinet, B¯ Trumpet, Soprano Sax, Horn in B¯ alto, Flugelhorn A* Down min. 3rd Up min. 3rd 2 -3 A Clarinet, Horn in A, Oboe d’Amore A¯ Down maj. 3rd Up maj. 3rd 2 4 Horn in A¯ G* Down perf. 4th Up perf. 4th 3 -1 Horn in G, Alto Flute G¯ Down aug. 4th Up aug. 4th 3 6 Horn in G¯ F# Down dim. -

8Th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map

8th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map Music Reading: Student will be able to read and perform one octave major and melodic minor scales in the keys of EbM/cm; BbM/gm; FM/dm; CM/am; GM/em; DM/bm; AM/f#m Student will be able to read and perform key changes. Student will be able to read and correctly perform accidentals and understand their duration. Student will be able to read and perform simple tenor clef selections in cello/bass; treble clef in viola Violin Students will be able to read and perform music written on upper ledger lines. Rhythm: Students will review basic time signature concepts Students will read, write and perform compound dotted rhythms, 32nd notes Students will learn and perform basic concepts of asymmetrical meter Students will review/reinforce elements of successful time signature changes Students will be able to perform with internal subdivision Students will be able to count and perform passages successfully with correct rhythms, using professional counting system. Students will be able to synchronize performance of rhythmic motives within the section. Students will be able to synchronize performance of the sections’ rhythm to the other sections of the orchestra. Pitch: Student is proficient in turning his/her own instrument with the fine tuners. Student is able to hear bottom open string of octave ring when top note is played. Students will review and reinforce tuning to perfect 5ths using the following methods: o tuning across the orchestra o listening and tuning to the 5ths on personal instrument. Student performs with good intonation within the section. -

Shifting Exercises with Double Stops to Test Intonation

VERY ROUGH AND PRELIMINARY DRAFT!!! Shifting Exercises with Double Stops to Test Intonation These exercises were inspired by lessons I had from 1968 to 1970 with David Smiley of the San Francisco Symphony. I don’t have the book he used, but I believe it was one those written by Dounis on the scientific or artist's technique of violin playing. The exercises were difficult and frustrating, and involved shifting and double stops. Smiley also emphasized routine testing notes against other strings, and I also found some of his tasks frustrating because I couldn’t hear intervals that apparently seemed so familiar to a professional musician. When I found myself giving violin lessons in 2011, I had a mathematical understanding of why it was so difficult to hear certain musical intervals, and decided not to focus on them in my teaching. By then I had also developed some exercises to develop my own intonation. These exercises focus entirely on what is called the just scale. Pianos use the equal tempered scale, which is the predominate choice of intonation in orchestras and symphonies (I NEED VERIFICATION THAT THIS IS TRUE). It takes many years and many types of exercises and activities to become a good violinist. But I contend that everyone should start by mastering the following double stops in “just” intonation: 1. Practice the intervals shown above for all possible pairs of strings on your violin or viola. Learn the first two first, then add one interval at a time. They get harder to hear as you go down the list for reasons having to do with the fractions: 1/2, 2/3, 3/4, 3/5, 4/5, 5/6. -

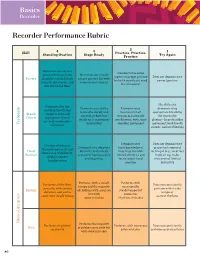

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

2015-2016 New Music Festival

Tenth Annual New Music Festival 4 events I 5 world premieres I 40 performers Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Composer-in Residence Lisa Leonard, Director February 23 - February 26, 2016 2015-2016 Season SPOTLIGHT I: YOUNG COMPOSERS Tuesday, February 23 at 7:30 p.m. Matthew Hakkarainen Florida MTNA winner (b.2000) The Suite for Three Animals (2015) Hopping Hare Growling Bear Galloping Mare Matthew Hakkarainen, violin David Jonathan Rogers Piano Trio, Op.10 (2015) (b. 1990) Arcs Fractals Collage Yasa Poletaeva, violin; Elizabeth Lee, cello Darren Matias, piano Trevor Mansell Six Miniatures for Wind Trio (2014) (b. 1996) World Premiere Pastorale Nocturne March Minuet Aubade Rondo Cameron Hewes, clarinet; Trevor Mansell, oboe Michael Pittman, bassoon Alfredo Cabrera (b. 1996) from The Whistler Suite, Op. 5 (2015-16) Innocence World Premiere Sadness & Avarice Beauty & Anger Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Pause Chen Liang Two movements from String Quartet (2015-2016) (b. 1991) World Premiere Andante Rondo Junheng Chen & Yvonne Lee, violins Hao Chang, viola; Nikki Khabaz Vahed, cello Anthony Trujillo The Four Nocturnes (2015) (b. 1995) World Premiere Matthew Calderon, piano Matthew Carlton Septet (2015) (b. 1992) World Premiere John Weisberg, oboe; Cameron Hewes, bass clarinet Hugo Valverde, French horn; Michael Pittman, bassoon Yaroslava Poletaeva, violin; Darren Matias, piano Anastasiya Timofeeva, celesta MASTER CLASS with ELLEN TAAFFE ZWILICH Wednesday, February 24 at 7:30 p.m. Selections from the following compositions by Lynn student composers will be performed and discussed. Alfredo Cabrera (b. 1996) from The Whistler Suite, Op. 5 (2015-16) Innocence Sadness & Avarice Beauty & Anger Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Chen Liang Two movements from String Quartet (2015-2016) (b. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

LISTENING GUIDE Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770–1827) Symphony No

LISTENING GUIDE Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Opus 67 • Composed 1803–1808 1st Performance in Vienna, December 22, 1808 Movement I Allegro con brio FORM: SONATA ALLEGRO EXPOSITION 1st Theme 1. 1st THEME introduced by two strong UNISONS. U U bb 2 ‰ ‰ & b 4 œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ ˙ ˙ 2. Close IMITATION leads to _______ CHORDS. Which INSTRUMENT “hangs on”? 3. Another (very loud) UNISON restarts the action. Transition 4. ASCENDING SEQUENCE of ____ steps based on ____________. (soft) 5. TRANSITION ends with _____ CHORDS. 2nd Theme 6. 2nd THEME poses Question (in E-FLAT MAJOR) b & b b œ œ œ ˙ ˙ ˙ and receives three simple Answers. b œ œ œ & b b œ œ œ œ œ Closing Section 7. Another stirring CRESCENDO. 8. Joyous idea (still in E-FLAT MAJOR) propels to end of EXPOSITION. ˙ œ œ œ. b bœ œ œ œ œ. œ œ . œ. œ œ . œ & b b œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ j . œ. œ ƒ Entire EXPOSITION repeats from No. 1. DEVELOPMENT 9. Strange twist in 1st THEME announces DEVELOPMENT. 10. Many KEYS visited. Tension builds! 11. RHYTHMIC surprises and SYNCOPATION abound. 12. WINDS and STRINGS engage in IMITATION. 13. Violent DYNAMIC contrasts drive to... RECAPITULATION 1st Theme 14. Two “almost” UNISON statements. 15. Forward motion of RECAPITULATION is interrupted by an _________ SOLO. Transition 16. ASCENDING SEQUENCE of _____ steps. 17. TRANSITION ends with ________ CHORDS. 2nd Theme 18. BASSOONS ask a Question (now in C MAJOR) followed by four simple Answers. -

New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon

Hayley Elizabeth Roud 300220780 NZSM596 Supervisor- Professor Donald Maurice Master of Musical Arts Exegesis 10 December 2010 New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon Contents 1 Introduction 3 2.1 History of the contrabassoon in the international context 3 Development of the instrument 3 Contrabassoonists 9 2.2 History of the contrabassoon in the New Zealand context 10 3 Selected New Zealand repertoire 16 Composers: 3.1 Bryony Jagger 16 3.2 Michael Norris 20 3.3 Chris Adams 26 3.4 Tristan Carter 31 3.5 Natalie Matias 35 4 Summary 38 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 45 Appendix C 47 Appendix D 54 Glossary 55 Bibliography 68 Hayley Roud, 300220780, New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon, 2010 3 Introduction The contrabassoon is seldom thought of as a solo instrument. Throughout the long history of contra- register double-reed instruments the assumed role has been to provide a foundation for the wind chord, along the same line as the double bass does for the strings. Due to the scale of these instruments - close to six metres in acoustic length, to reach the subcontra B flat’’, an octave below the bassoon’s lowest note, B flat’ - they have always been difficult and expensive to build, difficult to play, and often unsatisfactory in evenness of scale and dynamic range, and thus instruments and performers are relatively rare. Given this bleak outlook it is unusual to find a number of works written for solo contrabassoon by New Zealand composers. This exegesis considers the development of contra-register double-reed instruments both internationally and within New Zealand, and studies five works by New Zealand composers for solo contrabassoon, illuminating what it was that led them to compose for an instrument that has been described as the 'step-child' or 'Cinderella' of both the wind chord and instrument makers.