6-Winnie Bothe.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sikkim State Development Programme

SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 NIEPA DC llllllllllll D00458 - i S - > V Sub. r-'s’-r r '2 in$ U n i t , Kai:.-. ’ ' f Educatlon£ P k; __ ,i£i;fa'dofi 17-f,S -^Aurb#^ N ew PelBi-1100tt€ DOC. No../) 1301:6...............................•••/•......... CONTENTS page No. SSI. No. Subject I 1. Introduction 1 2. Agriculture 12 3. Land Reforms................................................................ 13 4. Minor Irrigation............................................................ 14 5. Soil Conservation............................................................... 17 6. Food & Civil Supplies ................................................. 7. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development ... 18 22 8. Fisheries and Wild L i f e .............................. 25 9. Forest ............... ................................................. 10. Panchayats........................... ..................................... 29 Co-opeTation ............................................................ 30 12. Flood Control .................................... ....................... 33 13 Power Development ................................................ 34 14. In d u stries.................................................... 38 15. Mining & Geology ................................................ 43 16. Roads & Bridges .......................... 45 17. Road Transport ......................... ........................ 55 18. Tourism ....................................................................... -

April-June, 2014

For Private Circulation only SIHHIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 6 Issue No.2 April-June, 2014 ~ 8 . STATE MEET OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS & DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITIES 26th APRIL, 2014 AUDITORIUM, HIGH COURT OF SIKKIM, GANGTOK ORGANISED BY: SIKKIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY Editorial Board Hon'ble Shri Justice Narendra Kumar Jain, Chief Justice, High Court of Sikkim and Patron-in-Chief, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Hon'ble Shri Justice Sonam P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Compiled by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division-11 and Member Secretary, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Quarterly newsletter published by Sikkim State Legal Services Authority, Gangtok. MEETING Wlnl niE PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS OF NORTH DISTRICT A meeting with the Principals of Schools and PLVs of North District was held on 5111 April, 2014 at ADR Centre, Pentok, Mangan. The meeting was chaired by Hon'ble Shri Justice S.P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim SLSNMember, Central Authority, NAI..SA. The mode of setting up of Legal Uteracy Clubs under the NAI..SA (Legal Services Clinics in Universities, Law Colleges Hon'ble Shrl Justice S.P. Wangdl, Exet;utJoe Chalrman, and Other Institutions) Scheme, 2013 was discussed Sikkim SLSA chairing the meeting during the meeting. The meeting was also attended by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division - 11/Member Secretary, Sikkim SLSA, Shri N.G. Sherpa, Registrar, High Court of Sikkim, Shri Jagat Rai, District & Sessions Judge, North/Chairman, DLSA (North), Shri Benoy Sharma, Civil Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate/Secretary, DLSA (North), Mangan, Mrs. -

ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE of SAI Manoj Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2994 ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE OF SAI Manoj Dr. K.S. Will the Minister of YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS be pleased to state: (a) whether SAI is upgrading its training infrastructure in its centres; and (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the names of centres, where training is giving for swimming particularly in Kerala ? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) IN THE MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS (SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER) (a) Yes, Sir. (b) A list containing Status of upgradation/creation of Sports Authority of India`s sports Infrastructure during the last three years is placed at Annexure-I. The talented sportspersons under SAI Schemes are imparted regular Swimming training in the following Centres:- Under NATIONAL SPORTS TALENT CONTEST (NSTC) Scheme (i) St. Joshope Indian High School, Bangalore (ii) Tashi Namgyal Academy, Gangtok (iii) Bhonsla Military School, Nasik (iv) Don Bosco High School, Guwahati (v) Moti Lal Nehru School of Sports, RAI (Sonepat) Under ARMY BOYS SPORTS COMPANY (ABSC) Scheme (i) MEG Centre, Bangalore (ii) BEG Centre Kirkee (Pune) Under SPECIAL AREA GAMES (SAG) Scheme (i) SAG Agartala (ii) SAG Imphal Under SAI TRAINING CENTRE (STC) Scheme (i) STC Kolkata (ii) STC Gandhinagar (iii) STC Ponda (iv) STC Guwahati (v) STC Trichur Under CENTRE OF EXCELLECE (COX) Scheme (i) Kolkata (ii) Gandhinagar In the State of Kerala, Swimming is a regular discipline at STC Trichur where training is imparted. In addition swimming pools are available at Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Swimming Complex, New Delhi, Netaji Subhash National Institute of Sports, Patiala and SAI Southern Region Centre at Bangalore. -

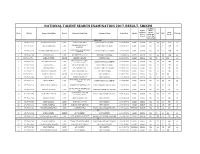

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status Residence (Please Total Sl

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status residence (please Total Sl. No. Roll No. Name of Candidates District Address of Candidates Address of School School Code Gender SAT MAT LT Marks (Rural/ verify and Marks Urban) attach the certificate) MERIT LIST 1 17170001202 INDRA BDR CHETTRI EAST PADAMCHEY EAST PADAMCHEY SEC SCHOOL 11040802902 MALE URBAN NIL 73 37 110 29 QRNO 6B /402 SUNCITY 2 17170001027 CHIRAG MARAGAL EAST ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 MALE URBAN NIL 72 37 109 37 RANIPOOL 3 17170001213 TSERING PHUNTSOK BHUTIA EAST TSHERING NORBU FL SHOP OPP/D/VILLA 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 68 40 108 43 CHANDMARI TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 4 17170001028 BHAVANA RAI EAST NO I DET ECCIU C/O 17 ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 68 37 105 39 5 17170003072 SUNIL CHETTRI SOUTH KEWZING SOUTH KEWZING SSS 11030205001 MALE RURAL NIL 72 32 104 28 ICICI ATM BLD OFF ENTEL 6 17170001210 PRANISH SHRESTHA EAST TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 65 35 100 37 MOTERS TADONG 7 17170001030 RANI KUMARI EAST STN HQ NEW CANTT GTK ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 67 32 99 40 8 17170001063 ANUSHA SUNAR EAST JNV PAKYONG EAST MIDDLE CAMP SEC SCHOOL 11040604701 FEMALE RURAL NIL 57 42 99 39 9 17170001172 BISWADEEP SHARMA EAST TAKTSE BOJOGARI EAST SIR TNSS SCHOOL 11040300801 MALE RURAL NIL 60 36 96 40 10 17170003105 BANDITA CHETTRI SOUTH MELLI KERABARI SOUTH JNV RAVONGLA 11030207301 FEMALE RURAL NIL 62 33 95 41 11 17170001066 NEHAL DAS EAST RONGLI BAZAR EAST JNV PAKYONG 11040100703 MALE URBAN -

Sikkim the Place and Sikkim the Documentary: Reading Political History Through the Life and After-Life of a Visual Representation

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 33 Number 1 Article 9 March 2014 Sikkim the Place and Sikkim the Documentary: Reading Political History through the Life and After-Life of a Visual Representation Suchismita Das University of Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Das, Suchismita. 2014. Sikkim the Place and Sikkim the Documentary: Reading Political History through the Life and After-Life of a Visual Representation. HIMALAYA 33(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol33/iss1/9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikkim the Place and Sikkim the Documentary: Reading Political History through the Life and After-Life of a Visual Representation Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr Mark Turin for all the encouragement and for the wonderfully insightful course on the visual representation of the Himalayas, from which the idea of this article germinated. I am grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and to Hope Cooke for their comments, which have helped -

Stories of the Lepcha

( (#&'#( $ &&(*'&#!#"('( " - &&- (( )!((") !"(#(&%)&!"('#&( &# #(#&# #'#$- "( ) (-#&('"# "' "*&'(-#"# #-/-"- 7568 &((#)(#&'$1&" (- ,.# 3.".."1),%#(."#-."-#-"-().*,0#)/-&3(-/'#.. ), !,(#-().#(!-/'#..-*,.) (#./, ),(3).",!,; &-),.# 3.".."."-#-"-(1,#..(3';(3"&*.". "0,#0 #('3,-,"1),%(."*,*,.#)() ."."-#-#.-& "-( %()1&!; (#.#)(8 ,.# 3.".&&#( ),'.#)(-)/,-(&#.,./, /-,#(#.#(."."-#-; #!(./,) (#. &&- (( 156558=86 ## "#+ !"(' (HFFL81"( .,0&&.)#%%#'(-.(!&.),),."-.),#-) ." *"8 ,,#01#."-&#')((.#)(-.)!(,)/-*)*&; "0'&)- ,#(-1")*,'#..'(#(-#,@---(#(.#'31"(,),#(!."#, -.),#-;"3&&)1'.)*,)1&,)/(1#.",),,8',( ().*8+/-.#)(#(!8&,# 3#(!8(#(-,.#(!'3(--,-,",#(.) ."#,�-;"3#(0#.'.)�#(."#,")'-8.)-",."#, ))($)#( ."#, '#&3&# ; '."(% /&(!,. /&.)." *")''/(#.#-#(#%%#'(-.(!& ),."#,--#-.(;#,-.8'3."(%-.) /((/,#**8 ),-/!!-.#(! ,), *"-.),#-81"#"&'.)."#,(& 1,(#.&#(!().", '#&3'',-1")"&*'#(.",&3-.!-) ,-,"; "'',-) .#.#4(-) -.8#(&/#(!,-#(.8."/* *" 1,)*((.,/-.#(!1#."."#,(,,.#0-( '#(..)."';" .,/-.(!(,)-#.3-")1(3"/(!,-.,#%,-1 *"((4#(! *" #-, &.#(&')-.0,3"*.,) ."#-."-#-;" (#!()/- *",#& --)#.#)(#(-.(!&8/(,."&,-"#*) $), 3(!-)(!'-(!= )(!8(3)/."&,-),$# *"(4/% *"8*,)0#0&/& #(-#!".#(.) *""#-.),38/-.)'-(&#.,./,; ((!.)% �#( +."")') ",* *"8"#-1# ")(8 ,).",' *"(."#,2.( '#&3;"3,'3#%%#' '#&3(8 -1&&-")'8*,)0#').#)(&-"&.,/,#(!&)(!*,#)-13 ,)' /-.,&#; &-)**,#.." ,#(-"#*- '.(!.)%@-/&./,&"/8 "())%-81",8()/,!3)1(,'(",-.8#%%#'@-,.#0 (#(+/#,#(!'#(-'. ),/&./,&0(.-()(0,-.#)(; ,+/(. 0#-#.),.)"(8."$)/,(&#-.#./&8#-%()1&! ),",,.#&-( ))%-( ),0#-#(!')(."#!!,*#./,) #%%#'-*)&#.#-; -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 43 NO. 1 AND 2 2007 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 43 NO. 1 AND 2 2007 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY SHRI BALMIKI PRASAD SINGH, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Assistant, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the history, language, art, culture and religion of the people of the Tibetan cultural area although we would particularly welcome articles focusing on Sikkim, Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. -

Full Article

LEPCHA NARRATIVES OF THEIR THREATENED SACRED LANDSCAPES Transforming Cultures eJournal, Vol. 3 No 1, February 2008 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/TfC Kerry Little1 Dorjee Tshering Lepcha rises with the sun each morning. He walks out of his living room into the crisp early air and enters a small prayer room. The room is sparsely decorated, an altar on one side and a cushion and small stool on the other. The altar is modestly adorned with leaves, flowers and fruit. Dorjee sits cross-legged on the floor, the cushion softening the impact of the cold concrete, and places the manuscript for a Lepcha prayer on a small stool in front of him. To his side, he rests a bamboo flute. First he chants; the morning chant to Mother Nature, informing her that he will surely intrude on her that day and asking her forgiveness in advance. Then he lifts the flute to his mouth and gently blows a welcome to the new day, its melancholy sound sending an apology simple and pure; its sincerity clear. In his village, Manegumboo, at 12th Mile in Kalimpong, the same ritual is taking place in seven of the 30 households. For these are animist homes, where the Children of Mother Nature live.2 Photo 1: Dorjee’s morning prayer to Mother Nature 1 Kerry Little is a PhD candidate at the University of Technology Sydney. 2 Dorjee’s village with its 25 percent animist homes is rare, for nature-worshipping Lepchas in the Darjeeling district make up just five percent2 of the Lepcha population. -

Impact of National Coaching Scheme of Sports Authority of India: a Study on Sports Promotion in the Eastern Region

IMPACT OF NATIONAL COACHING SCHEME OF SPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA: A STUDY ON SPORTS PROMOTION IN THE EASTERN REGION Sponsored By PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi Submitted By INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT OF BACKWARD REGIONS BHUBANESWAR DECEMBER, 2002 1 CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE (i) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT (ii) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (xii) Sl.No. C H A P T E R S (I) INTRODUCTION 01-09 1.0 Background 1.1 Sports in Independent India 1.2 The Problem 1.3 Need for the Study 1.4 Hypotheses 1.5 Objectives 1.6 Methodology 1.6.1 Study Design 1.6.2 Statistical Frame 1.6.3 Tools of Observation 1.7 Manpower Deployment 1.8 Field work and Data Analysis 1.9 Reporting Plan (II) NATIONAL SPORTS POLICY AND PROGRAMMES 10-34 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The Govt. of India Policies and Programmes 2.2.1 Policies 2.2.2 Sports Programmes 2.2.2.1 Grants Creation of Sports Infrastructure 2.2.2.2 Grants to Rural Schools for Purchase of Sports Equipment and Development of Playgrounds 2.2.2.2 Scheme for Installation of Synthetic Playing Surfaces 2 Sl.No. C O N T E N T S Page No. 2.2.2.4 Grants for Promotion of Sports in Universities and Colleges. 2.2.2.5 Assistance to National Sports Federations 2.2.2.6 Sports Talent Search Scholarship Scheme 2.2.2.7 Sports Science Research fellowship scheme 2.2.2.8 Arjun Award 2.2.2.9 Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award 2.2.2.10 Cash Award to Medal Winners in International Sports Events 2.2.2.11 National Sports Development Fund 2.2.2.12 Assistance to Promising Sports Persons and Supporting Personnel 2.2.2.13 Exchange of Sports and Physical Education Teams / Experts. -

Faculty Profile

FACULTY PROFILE NAME: PRISCELLA GHIMIRAY E-MAIL: [email protected] DESIGNATION: ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT: EDUCATION PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: M.A (EDUCATION), M.PHIL (EDUCATION), P.HD (REGISTERED UNDER NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY) TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Worked as Assistant teacher (permanent position) in Mount Zion School, Gangtok, Sikkim from 2016-18. Worked as Assistant teacher in Tashi Namgyal Academy for the academic session 2018-19. Presently employed as Assistant Professor from 01.07.2019 till date in Salesian College Siliguri campus affiliated under North Bengal University. AWARDS/RECOGNITION RECEIVED: Gold medal in M.A (Sikkim University). WORKSHOP/WEBINAR/PROGRAMS ATTENDED AND PARTICIPATED: Sl. No. TOPIC ORGANISED BY YEAR 1. Addressing Regional Disparity in Higher The Department of 2015 Education in India Education, Sikkim University 2. Participated in the National Service Southfield College, North 2012-13 Scheme Unit Bengal University 3. Participated in Virtual Conference – St. Anthony’s College, 2020 Adapting to a changing world Shillong, Meghalaya, (E21ACW): Education in the 21st India century. 4. Participated in Faculty Development St. Anthony’s College, 2020 Programme Live Webinar Shillong, Meghalaya, India 5. Participated in Research Methodology Salesian College, Siliguri, 2020 Workshop organised by Salesian College, North Bengal University Siliguri Campus on 22.02.2020 6. Participated in Faculty Development Salesian College, North 2020 Programme of ‘Journey with Bengal University Management Learning System Moodle’ 7. Participated in Two-day Webinar on Don Bosco College, 2020 Research & Education: During and After Golaghet Covid-19 8. Participated in National Webinar Digital Vidyasagar College of 2020 Transformation: A Progressive Approach Education 9. Participated in a one-day webinar on Salesian College Sonada 2020 Mental Health of Students: Educational & Siliguri Implications, Issues and Challenges 10. -

Userfiles/Boarding Schools Regional Rankings.Pdf

COVER STORY EW Boarding Schools Survey 2011 Boarding Schools: Regional Rankings ESPITE ADOPTION OF AMERICAN LIFESTYLES AND NORMS which tend to favour day over boarding schools, DBritish-style boarding schools with their rough and tumble public school ethos, continue to be much loved by India’s westernised and aspirational middle class. But while throughout the 20th century, upper class households — which were quick to appreciate the value of disciplined primary-secondary education — were prepared to send their children across the country for a Tom Brown’s Schooldays- type of cold-showers-and-the-lash education, in the new millennium the rationale for sending children to boarding school has undergone a sea change. Residential schools, including new genre ‘international’ schools, which have mushroomed all over the country, especially in salubrious hill stations or sites far away from the nation’s noisy, crowded and polluted cities where playing fields have almost disappeared, long commutes to school are routine and the very air is dangerous to inhale, continue to VDJS’ Bindra: conscious improvement effort offer an attractive alternative to day schools. But with rules relating to visitation and weekends at home becoming more useful purpose of prompting school managements to take relaxed and liberal, latter day affluent upper and middle class stock and figure out ways and means to improve themselves households prefer to enrol the children in boarding schools across the entire range of assessment parameters. The latest within easy driving (or flying) distance. survey results have come as a shot in the arm for the Vidya Although some of the legendary glamour of traditional Devi Jindal School where we are consciously working to boarding schools has been stolen by highly capital-intensive improve performance across all the parameters. -

NOW 2003 09 10.Pdf

10-16 September, 2003; NOW! 1 SOUTH-EAST ASIA editorial: 2-DIGIT DILEMMA DISCOUNTED GANGTOK, WEDNESDAY, 10 - 16 September, 2003 AIR TICKETS TOUR FOR INSTANT RESERVATIONS CALL: CALL FOR BOOKING: Pineridge Travels Tashila Jet Airways Sales Agent TOURS & TRAVELS The Oriental 94341-53567 Mahatma Gandhi Marg Telephone: Gangtok 229842 / 222978 SIKKIMNOW! MATTERS VOL 2 NO 12 Rs. 5 Ph: 221182 / 221181 / 221180 A NOW! SPECIAL FOR COMECOME TOGETHERTOGETHER PANG LHABSOL INSIDE NOOSENOOSE TIGHTENS ON Imagine being packed off to SIKKIM POLICE PIECES TOGETHER Malaysia with promises of HOW THESE DREAM MERCHANTS employment only to find out that you are travelling on a SOLD NIGHTMARES OF MALAYSIA tourist visa. You have no SIKKIM’S money for the return fare. What do you do? Many Sikkimese youth who fell for the smooth-talking RK Subba were faced with a BODY-SHOPPERSSHOPPERS similar predicament... TURN TO pg 3 FOR DETAILS SALE SALE SALE ‘Good news for you first time in go Sikkim’ NEW STOCK!!! 24,647 SQ. FT. Bombay Saree & Dress Materials for 50% DISCOUNT ON SAREES AND KURTA PYJAMAS twelve Pure Chiffon, Dani Chiffon, Apoorva Silk, Georgette, Rasgull Crabe, FOR POSITIVE Kanjeevaram, Pure Silk, Pure Cotton, Banarasi Saree & Kurta, Italian Silk, Embroidery Saree, 40 gm silk, Pure Cotton, Devdas Saree & many more varieties. IN OPEN EVERYDAY THINKING ON pg 4 Hotel Bayul, MG Marg extras Near Krishi Bhawan, Tadong, Gangtok. Phone: 270876 Below Power Deptt, Kazi Road, Gangtok. Level 1: Diploma in IT foundation Phone: 227917 Level 2: Hon’s Diploma in Web Programming