Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probabilistic Travel Model of Gangtok City, Sikkim, India FINAL.Pdf

European Journal of Geography Volume 4, Issue2: 46-54, 2013 © Association of European Geographers ANALYSIS OF TOURISM ATTRACTIVENESS USING PROBABILISTIC TRAVEL MODEL: A STUDY ON GANGTOK AND ITS SURROUNDINGS Suman PAUL Krishnagar Govt. College, Department of Geography Nadia, West Bengal, India. Pin-741101 http://www.krishnagargovtcollege.org/ [email protected] Abstract: Tourism is now one of the largest industries in the world that has developed alongside the fascinating concept of eco-tourism. The concept of tourism could be traced back to ancient times when people travelled with a view to acquiring knowledge of unknown lands and people, for the development of trade and commerce, for religious preaching and also for the sheer adventure of discovery. In fact the system of tourism involves a combination of travel, destination and marketing, which lead to a process of its cultural dimension. Gangtok as a core centre of Sikkim has potential command area over different tourist spots in East Sikkim, which are directly linked by a network of roads centering Gangtok and are perfectly accessible for one-day trips. The tourist attractions of East Sikkim are clustered mostly in and around Gangtok, the state capital. This study shows the tourism infrastructure as well as seasonal arrival of tourists in the Gangtok city and to develop the probabilistic travel model on the basis of tourist perception which will help the tourism department for the further economic development of the area. KeyWords: Eco-tourism, command area, tourist attractions, probabilistic travel model 1. INTRODUCTION Tourism is now one of the largest industries in the world that has developed alongside the fascinating concept of eco-tourism. -

Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (Glofs)

IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: GLACIAL LAKE OUTBURST FLOODS (GLOFS) Binay Kumar and T.S. Murugesh Prabhu ABSTRACT orldwide receding of mountain glaciers is one of the most reliable evidences of the changing global climate. In high mountainous terrains, with the melting of glaciers, the risk of glacial Wrelated hazards increases. One of these risks is Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs). As glaciers retreat, glacial lakes form behind moraine or ice ‘dams’. These ‘dams’ are comparatively weak and can breach suddenly, leading to a discharge of huge volume of water and debris. Such outbursts have the potential of releasing millions of cubic meters of water in a few hours causing catastrophic flooding downstream with serious damage to life and property. Glacier thinning and retreat in the Sikkim Himalayas has resulted in the formation of new glacial lakes and the enlargement of existing ones due to the accumulation of melt-water. Very few studies have been conducted in Sikkim regarding the impacts of climate change on GLOFs. Hence a time-series study was carried out using satellite imageries, published maps and reports to understand the impacts of climate change on GLOFs. The current study is focussed on finding the potential glacial lakes in Sikkim that may be vulnerable to GLOF. The results show that some of the glacial lakes have grown in size and are vulnerable to GLOF. Though extensive research is required to predict GLOFs, it is recommend that an early warning system, comprising of deployment of real time sensors network at vulnerable lakes, coupled with GLOF simulation models, be installed for the State. -

Sikkim State Development Programme

SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 NIEPA DC llllllllllll D00458 - i S - > V Sub. r-'s’-r r '2 in$ U n i t , Kai:.-. ’ ' f Educatlon£ P k; __ ,i£i;fa'dofi 17-f,S -^Aurb#^ N ew PelBi-1100tt€ DOC. No../) 1301:6...............................•••/•......... CONTENTS page No. SSI. No. Subject I 1. Introduction 1 2. Agriculture 12 3. Land Reforms................................................................ 13 4. Minor Irrigation............................................................ 14 5. Soil Conservation............................................................... 17 6. Food & Civil Supplies ................................................. 7. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development ... 18 22 8. Fisheries and Wild L i f e .............................. 25 9. Forest ............... ................................................. 10. Panchayats........................... ..................................... 29 Co-opeTation ............................................................ 30 12. Flood Control .................................... ....................... 33 13 Power Development ................................................ 34 14. In d u stries.................................................... 38 15. Mining & Geology ................................................ 43 16. Roads & Bridges .......................... 45 17. Road Transport ......................... ........................ 55 18. Tourism ....................................................................... -

April-June, 2014

For Private Circulation only SIHHIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 6 Issue No.2 April-June, 2014 ~ 8 . STATE MEET OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS & DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITIES 26th APRIL, 2014 AUDITORIUM, HIGH COURT OF SIKKIM, GANGTOK ORGANISED BY: SIKKIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY Editorial Board Hon'ble Shri Justice Narendra Kumar Jain, Chief Justice, High Court of Sikkim and Patron-in-Chief, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Hon'ble Shri Justice Sonam P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Compiled by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division-11 and Member Secretary, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Quarterly newsletter published by Sikkim State Legal Services Authority, Gangtok. MEETING Wlnl niE PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS OF NORTH DISTRICT A meeting with the Principals of Schools and PLVs of North District was held on 5111 April, 2014 at ADR Centre, Pentok, Mangan. The meeting was chaired by Hon'ble Shri Justice S.P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim SLSNMember, Central Authority, NAI..SA. The mode of setting up of Legal Uteracy Clubs under the NAI..SA (Legal Services Clinics in Universities, Law Colleges Hon'ble Shrl Justice S.P. Wangdl, Exet;utJoe Chalrman, and Other Institutions) Scheme, 2013 was discussed Sikkim SLSA chairing the meeting during the meeting. The meeting was also attended by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division - 11/Member Secretary, Sikkim SLSA, Shri N.G. Sherpa, Registrar, High Court of Sikkim, Shri Jagat Rai, District & Sessions Judge, North/Chairman, DLSA (North), Shri Benoy Sharma, Civil Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate/Secretary, DLSA (North), Mangan, Mrs. -

The PLATEAU – North Sikkim

JAPANESE ALPINE NEWS 2013 ● HARISH KAPADIA THE PLATEAU Mountains of Sikkim – China Border This was my fifth visit to the mountains of Sikkim. As a young student I was part of the training course of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in 1964. The mountains of west Sikkim, like Kabru, Rathong, Pandim and host of others were attractive to my young eyes. I returned in 1976. No sooner Sikkim became a state on India two us, Zerksis Boga and I obtained permits and roamed the valleys for more than a month in the northwest Sikkim, covering Zemu glacier, Lhonak valley Muguthang, Lugnak la, Sebu la and returned via the Lachung valley. I returned a few times to Darjeeling and Sikkim valleys visiting the Singalila ridge, lakes of lower Sikkim and surroundings of Gangtok and Kalimpong. If you stretch the area to the south, I made several visits to Darjeeling and nearby hills over the years. Moreover in Sikkim the approach to different valleys is so varied that it gives a feeling of trekking in different Himalayan zones. 1 High Himalayan Unknown Valleys, by Harish Kapadia, p.156. (Indus Books, New Delhi, 2001). Also Himalayan Journal, Vol.35, p.181 57 ● JAPANESE ALPINE NEWS 2013 In no other country on earth can one find such a variety of micro-climates within such a short distance as Sikkim, declared the eminent English botanist and explorer Joseph Hooker in his Himalayan Journals (1854), which documented his work collecting and classifying thousands of plants in the Himalaya in the mid-19th century. In the shadow of the Himalayas, by John Claude White, 1883 – 1908. -

ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE of SAI Manoj Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2994 ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE OF SAI Manoj Dr. K.S. Will the Minister of YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS be pleased to state: (a) whether SAI is upgrading its training infrastructure in its centres; and (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the names of centres, where training is giving for swimming particularly in Kerala ? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) IN THE MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS (SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER) (a) Yes, Sir. (b) A list containing Status of upgradation/creation of Sports Authority of India`s sports Infrastructure during the last three years is placed at Annexure-I. The talented sportspersons under SAI Schemes are imparted regular Swimming training in the following Centres:- Under NATIONAL SPORTS TALENT CONTEST (NSTC) Scheme (i) St. Joshope Indian High School, Bangalore (ii) Tashi Namgyal Academy, Gangtok (iii) Bhonsla Military School, Nasik (iv) Don Bosco High School, Guwahati (v) Moti Lal Nehru School of Sports, RAI (Sonepat) Under ARMY BOYS SPORTS COMPANY (ABSC) Scheme (i) MEG Centre, Bangalore (ii) BEG Centre Kirkee (Pune) Under SPECIAL AREA GAMES (SAG) Scheme (i) SAG Agartala (ii) SAG Imphal Under SAI TRAINING CENTRE (STC) Scheme (i) STC Kolkata (ii) STC Gandhinagar (iii) STC Ponda (iv) STC Guwahati (v) STC Trichur Under CENTRE OF EXCELLECE (COX) Scheme (i) Kolkata (ii) Gandhinagar In the State of Kerala, Swimming is a regular discipline at STC Trichur where training is imparted. In addition swimming pools are available at Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Swimming Complex, New Delhi, Netaji Subhash National Institute of Sports, Patiala and SAI Southern Region Centre at Bangalore. -

Sikkim University

Local Response to Global Environmental Initiatives: A Study of Sikkim A Dissertation Submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By Namrata Rai Department of International Relations School of Social Sciences February 2017 Gangtok 737102 INDIA Date:6/2/2017 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation entitled “Local Response to Global Environmental Initiatives: A Study of Sikkim” submitted to Sikkim University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy is my original work. This dissertation has not been submitted for any other degree of this university or any other university. Namrata Rai Registration No: 13SU11884 Roll No: 15MPIR05 The Department recommends that this dissertation be placed before the examiner for evaluation Dr. Manish Dr. Sebastian N. Head of the Department Supervisor February 6, 2017 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “Local Response to Global Environmental Initiatives: A Study of Sikkim” submitted to Sikkim University for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in International Relations, embodies the result of bona fide research work carried out by Namrata Rai under my guidance and supervision. No part of the dissertation is submitted for any other degrees, diploma, associate- ship and fellowship. All the assistance and help received during the course of investigation have been deeply acknowledged by her. Dr. Sebastian N. Supervisor Department of International Relations School of Social Sciences Sikkim University Place: Gangtok Date: 06.02.2017 PLAGIARISM CHECK CERTIFICATE This is to certify that plagiarism check has been carried out for the following M.Phil dissertation with the help of URKUND software and the result is within the permissible limit decided by University. -

Ground Water Scenario of Himalaya Region, India

Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region, India laiknu@Edited By: lq'khy xqIrk v/;{k Sushil Gupta Chairman Central Ground Water Board dsanzh; Hkwfe tycksMZ Ministry of Water Resources ty lalk/ku ea=kky; Government of India Hkkjr ljdkj 2014 Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; vuqØef.kdk dk;Zdkjh lkjka'k i`"B 1- ifjp; 1 2- ty ekSle foKku 23 3- Hkw&vkd`fr foKku 34 4- ty foKku vkSj lrgh ty mi;kst~;rk 50 5- HkwfoKku vkSj foorZfudh 58 6- Hkwty foKku 73 7- ty jlk;u foKku 116 8- Hkwty lalk/ku laHkko~;rk 152 9- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k esa Hkwty fodkl ds laca/k esa vfHktkr fo"k; vkSj leL;k,a 161 10- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k ds Hkwty fodkl gsrq dk;Zuhfr 164 lanHkZ lwph 179 Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region of India CONTENTS Executive Summary i Pages 1. Introduction 1 2. Hydrometeorology 23 3. Geomorphology 34 4. Hydrology and Surface Water Utilisation 50 5. Geology and Tectonics 58 6. Hydrogeology 73 7. Hydrochemistry 116 8. Ground Water Resource Potential 152 9. Issues and problems identified in respect of Ground Water Development 161 in Himalayan Region of India 10. Strategies and plan for Ground Water Development in Himalayan Region of India 164 Bibliography 179 ifêdkvks dh lwph I. iz'kklfud ekufp=k II. Hkw vkd`fr ekufp=k III. HkwoSKkfud ekufp=k d- fgeky; ds mRrjh vkSj if'peh [kaM [k- fgeky; ds iwohZ vkSj mRrj iwohZ [kaM rFkk iwoksZRrj jkT; IV. -

Rapid Biodiversity Survey Report-I 1

RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORt-I 1 RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORT - I Bistorta vaccinifolia Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project (SBFP) Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management Department Government of Sikkim Rhododendron barbatum Published by : Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project (SBFP) Department of Forests, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim, Deorali, Gangtok - 737102, Sikkim, India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Department of Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim, Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Project Director, Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project, Department of Forests, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim. 2 RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORt-I Contents Page No. 5 Message 6 Forward 7 Preface 8 Acknowledgement 9 Introduction 12 Rapid Biodiversity Survey. 14 Methodology 16 Sang - Tinjurey sampling path in Fambonglho Wildlife Sanctuary, East Sikkim. 24 Yuksom - Dzongri - Gochela sampling path of Kanchendzonga Biosphere reserve, West Sikkim 41 Ravangla - Bhaleydunga sampling path, Maenam Wildlife Sanctuary, South Sikkim. 51 Tholoung - Kishong sampling path, Kanchendzonga National Park, North Sikkim. -

Conservation & Adaptation In

Conservation & Adaptation in Asia’s High Mountains Issue #2 | July 2016 worldwildlife.org/AHM Research: female snow leopard fitted with GPS collar in Nepal. Her collar will provide conservationists with valuable 2 information that will help safeguard the future of snow leopards. Saving Snow Leopards: good news from Mongolia Participants at the GSLEP workshop. ©WWF-US and Pakistan. Children in Mongolia led a 3 UPDATE FROM GSLEP successful campaign to save snow leopards from traps, while Workshop on Landscape Management Pakistan has been able to reduce snow leopard killings drastically. Planning to Conserve the Snow Leopard Written by Matthias Fiechter, Snow Leopard Trust Climate: inside a Earlier this spring, experts and representatives from nine snow Kyrgyz effort to leopard range countries met in Kathmandu, Nepal, for a workshop manage river basins. on climate smart conservation planning at the landscape level to protect the iconic snow leopard. Communities are working on a watershed management plan that 3 Snow leopards use vast home ranges of several hundred square will safeguard the Chon Kyzyl-Suu kilometers. To protect them, the twelve snow leopard range river basin in a changing climate. countries identified the need to go beyond isolated protected areas and conduct conservation efforts at a larger landscape level. In October 2013, all 12 range countries came together and Sustainable unanimously endorsed the Bishkek Declaration on Snow Leopard Livelihoods: Conservation that culminated into the Global Snow Leopard and communities in India Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP). and Bhutan taking This workshop was part of the GSLEP process to secure 20 snow care of nature. -

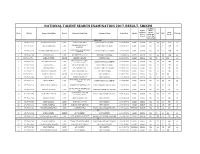

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status Residence (Please Total Sl

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status residence (please Total Sl. No. Roll No. Name of Candidates District Address of Candidates Address of School School Code Gender SAT MAT LT Marks (Rural/ verify and Marks Urban) attach the certificate) MERIT LIST 1 17170001202 INDRA BDR CHETTRI EAST PADAMCHEY EAST PADAMCHEY SEC SCHOOL 11040802902 MALE URBAN NIL 73 37 110 29 QRNO 6B /402 SUNCITY 2 17170001027 CHIRAG MARAGAL EAST ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 MALE URBAN NIL 72 37 109 37 RANIPOOL 3 17170001213 TSERING PHUNTSOK BHUTIA EAST TSHERING NORBU FL SHOP OPP/D/VILLA 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 68 40 108 43 CHANDMARI TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 4 17170001028 BHAVANA RAI EAST NO I DET ECCIU C/O 17 ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 68 37 105 39 5 17170003072 SUNIL CHETTRI SOUTH KEWZING SOUTH KEWZING SSS 11030205001 MALE RURAL NIL 72 32 104 28 ICICI ATM BLD OFF ENTEL 6 17170001210 PRANISH SHRESTHA EAST TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 65 35 100 37 MOTERS TADONG 7 17170001030 RANI KUMARI EAST STN HQ NEW CANTT GTK ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 67 32 99 40 8 17170001063 ANUSHA SUNAR EAST JNV PAKYONG EAST MIDDLE CAMP SEC SCHOOL 11040604701 FEMALE RURAL NIL 57 42 99 39 9 17170001172 BISWADEEP SHARMA EAST TAKTSE BOJOGARI EAST SIR TNSS SCHOOL 11040300801 MALE RURAL NIL 60 36 96 40 10 17170003105 BANDITA CHETTRI SOUTH MELLI KERABARI SOUTH JNV RAVONGLA 11030207301 FEMALE RURAL NIL 62 33 95 41 11 17170001066 NEHAL DAS EAST RONGLI BAZAR EAST JNV PAKYONG 11040100703 MALE URBAN -

Medical Tourism-Entrepreneurship Prospects in India's North East

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 7, Issue 1, Jan 2019, 413-430 © Impact Journals MEDICAL TOURISM-ENTREPRENEURSHIP PROSPECTS IN INDIA'S NORTH EAST Shahnoor Rahman Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, DKD College, Dergaon, Assam, India Received: 23 Jan 2019 Accepted: 28 Jan 2019 Published: 31 Jan 2019 ABSTRACT Medical tourism is a growing sector in India. In October 2015, India's medical tourism sector was estimated to be worth US$3 billion. It is projected to grow to $7–8 billion by 2020. According to the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII), the primary reason that attracts medical value travel to India is cost-effectiveness and treatment from accredited facilities at par with developed countries at much lower cost. Northeast India is well blessed by Nature. It has rich cultural heritage and exotic presence of flora and fauna. Besides having spectacular biodiversity, wildlife, snow- capped Himalayas, tropical forests, shrines of diverse religions, and prominent archaeological sites, Northeast India provides an immense opportunity for medical tourism. So, medical treatment in the Northeast means adding new life to health. KEYWORDS: Cost-Effectiveness and Treatment, Day-to-Day Activities and Achievements INTRODUCTION Medical tourism refers to the activity of people traveling from one place to another to get the medical benefits which are not available at their own location. In its initial stages, it meant traveling from developing to the developed Nations in search of better health care and treatment facilities. However, nowadays, the tables have turned in favor or the developing Nations.