Bulletin of Tibetology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dzongu Ecotourism Promotion Zone

SIKKIM GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Gangtok Friday 15th December, 2006 No. 400 Government of Sikkim Office of the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests-cum-Secretary Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management Department, Gangtok- 737 102, Sikkim. No: 1975/F Dated: 11.12.2006 NOTIFICATION Dzongu Ecotourism Promotion Zone WHEREAS, for most of the indigenous people living adjacent to the Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve, farming of large cardamom (Ammomum subulatum roxburgh) is the main source of cash income, and over the last few years, this crop has been severely affected due to severe borer and viral disease attack. The income of the household is dependent on this single livelihood option. The biggest challenge is how to diversify the farm income by providing diversified options for income generation. It is essential to provide sustainable livelihood options to the local community so that they do not resort to unsustainable practices. Hence it is proposed to promote the Dzongu Ecotourism Promotion Zone within the Khangchendzonga National Park for incentive programmes such as community based ecotourism. AND WHEREAS, though community based ecotourism is an important source of seasonal income for the villagers residing in remote areas. The impacts of unmanaged tourism are accelerating the rate of destruction in areas, which were once regarded as inaccessible. The negative impacts of unplanned tourism like deforestation due to the use of firewood, unhygienic sanitation, garbage accumulation, smuggling of plants and animals have to be regulated and at the same time the benefits arising from this enterprise equitably shared. Unplanned tourism also threatens sensitive and biologically important high altitude wetlands. -

West Sikkim Villages and Panchayat List

West Sikkim Villages and Panchayat List S. State District Block Name Panchayat Name Village Name No. Name Name ARITHANG 1 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG ARITHANG CHONGRANG ARITHANG ARITHANG 2 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG CHONGRANG CHONGRANG ARITHANG 3 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG CHONGRANG CHONGRANG DHUPIDARA 4 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG DHUPIDARA NARKHOLA DHUPIDARA DHUPIDARA 5 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG NARKHOLA NARKHOLA DHUPIDARA 6 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG NARKHOLA NARKHOLA 7 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG GERETHANG GERETHANG 8 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG GERETHANG LABING 9 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG KARZI MANGNAM KARZI MANGNAM 10 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG KARZI MANGNAM MANGNAM 11 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG KONGRI LABDANG KONGRI 12 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG KONGRI LABDANG KONGRI LABDANG 13 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG KONGRI LABDANG LABDANG 14 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG TASHIDING GANGYAP 15 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG TASHIDING LASSO 16 SIKKIM WEST CHONGRANG TASHIDING TASHIDING 17 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG CHAKUNG CHAKUNG 18 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG CHUMBONG CHUMBONG GELLING 19 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG GELLING BAIGUNEY MENDOGAON 20 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG MENDO-GOAN BERBOTEY 21 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG SAMSING PIPALEY SAMSING 22 SIKKIM WEST CHUMBUNG ZOOM ZOOM 23 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN LOWER FAMBONG DHALLAM 24 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN LOWER FAMBONG LOWER FAMBONG LUNGCHOK 25 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN LUNGCHOK SALYANGDANG LUNGCHOK 26 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN SALYANGDANG SALYANGDANG 27 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN OKHREY OKHREY 28 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN RIBDI BHARENG BHARENG 29 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN RIBDI BHARENG RIBDI 30 SIKKIM WEST DARAMDIN RUMBUK BURIKHOP(RUMBUK) -

Sikkim State Development Programme

SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT GANGTOK SIKKIM STATE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1981-82 NIEPA DC llllllllllll D00458 - i S - > V Sub. r-'s’-r r '2 in$ U n i t , Kai:.-. ’ ' f Educatlon£ P k; __ ,i£i;fa'dofi 17-f,S -^Aurb#^ N ew PelBi-1100tt€ DOC. No../) 1301:6...............................•••/•......... CONTENTS page No. SSI. No. Subject I 1. Introduction 1 2. Agriculture 12 3. Land Reforms................................................................ 13 4. Minor Irrigation............................................................ 14 5. Soil Conservation............................................................... 17 6. Food & Civil Supplies ................................................. 7. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development ... 18 22 8. Fisheries and Wild L i f e .............................. 25 9. Forest ............... ................................................. 10. Panchayats........................... ..................................... 29 Co-opeTation ............................................................ 30 12. Flood Control .................................... ....................... 33 13 Power Development ................................................ 34 14. In d u stries.................................................... 38 15. Mining & Geology ................................................ 43 16. Roads & Bridges .......................... 45 17. Road Transport ......................... ........................ 55 18. Tourism ....................................................................... -

April-June, 2014

For Private Circulation only SIHHIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 6 Issue No.2 April-June, 2014 ~ 8 . STATE MEET OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS & DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITIES 26th APRIL, 2014 AUDITORIUM, HIGH COURT OF SIKKIM, GANGTOK ORGANISED BY: SIKKIM STATE LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY Editorial Board Hon'ble Shri Justice Narendra Kumar Jain, Chief Justice, High Court of Sikkim and Patron-in-Chief, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Hon'ble Shri Justice Sonam P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Compiled by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division-11 and Member Secretary, Sikkim S.L.S.A. Quarterly newsletter published by Sikkim State Legal Services Authority, Gangtok. MEETING Wlnl niE PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS OF NORTH DISTRICT A meeting with the Principals of Schools and PLVs of North District was held on 5111 April, 2014 at ADR Centre, Pentok, Mangan. The meeting was chaired by Hon'ble Shri Justice S.P. Wangdi, Judge, High Court of Sikkim and Executive Chairman, Sikkim SLSNMember, Central Authority, NAI..SA. The mode of setting up of Legal Uteracy Clubs under the NAI..SA (Legal Services Clinics in Universities, Law Colleges Hon'ble Shrl Justice S.P. Wangdl, Exet;utJoe Chalrman, and Other Institutions) Scheme, 2013 was discussed Sikkim SLSA chairing the meeting during the meeting. The meeting was also attended by Shri K.W. Bhutia, District & Sessions Judge, Special Division - 11/Member Secretary, Sikkim SLSA, Shri N.G. Sherpa, Registrar, High Court of Sikkim, Shri Jagat Rai, District & Sessions Judge, North/Chairman, DLSA (North), Shri Benoy Sharma, Civil Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate/Secretary, DLSA (North), Mangan, Mrs. -

Strategic Urban Plan …………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…16

S I K K I M S T R A T E G I C P L A N 1 S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 8 Acknowledgement Surbana International Consultants would like to thank the Government of Sikkim and the following departments for their assistance in this project by providing the project team statistical information, advice and updates. Block Development Office Department of Economics, Statistics, Monitoring & Evaluation District Collectorates Education Department Energy & Power Department Forest Department Health Care Human Services & Family Welfare Department Land Revenue Department Mines, Minerals & Geology Department Roads & Bridges Department Rural Management Development Department Tourism Department Transport Department Urban Development & Housing Department Water Security & Public Health Engineering Department S I K K I M S T R A T E G I C P L A N 2 S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 8 Acknowledgement In particular, great appreciation is expressed to: The State Level Steering Committee, which consists of Additional Chief Secretary (Chairman) Secretary-In-Charge, Urban Development & Housing Department Secretary-In-Charge, Tourism Department PCE-cum-Secretary, Roads & Bridges Department PCE-cum-Secretary, Water Security and Public Health Engineering Department Director, Mines, Minerals and Geology Department Director, Department of Economics, Statistics, Monitoring & Evaluation Town Planning Section of Urban Development & Housing Department Mrs Devika Chhetri, Joint Chief Town Planner Mr Rajesh Pradhan, Team Head Mr Dinker Gurung, Gangtok in-charge -

ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE of SAI Manoj Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2994 ANSWERED ON:22.03.2005 CENTRE OF SAI Manoj Dr. K.S. Will the Minister of YOUTH AFFAIRS AND SPORTS be pleased to state: (a) whether SAI is upgrading its training infrastructure in its centres; and (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the names of centres, where training is giving for swimming particularly in Kerala ? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) IN THE MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS (SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER) (a) Yes, Sir. (b) A list containing Status of upgradation/creation of Sports Authority of India`s sports Infrastructure during the last three years is placed at Annexure-I. The talented sportspersons under SAI Schemes are imparted regular Swimming training in the following Centres:- Under NATIONAL SPORTS TALENT CONTEST (NSTC) Scheme (i) St. Joshope Indian High School, Bangalore (ii) Tashi Namgyal Academy, Gangtok (iii) Bhonsla Military School, Nasik (iv) Don Bosco High School, Guwahati (v) Moti Lal Nehru School of Sports, RAI (Sonepat) Under ARMY BOYS SPORTS COMPANY (ABSC) Scheme (i) MEG Centre, Bangalore (ii) BEG Centre Kirkee (Pune) Under SPECIAL AREA GAMES (SAG) Scheme (i) SAG Agartala (ii) SAG Imphal Under SAI TRAINING CENTRE (STC) Scheme (i) STC Kolkata (ii) STC Gandhinagar (iii) STC Ponda (iv) STC Guwahati (v) STC Trichur Under CENTRE OF EXCELLECE (COX) Scheme (i) Kolkata (ii) Gandhinagar In the State of Kerala, Swimming is a regular discipline at STC Trichur where training is imparted. In addition swimming pools are available at Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Swimming Complex, New Delhi, Netaji Subhash National Institute of Sports, Patiala and SAI Southern Region Centre at Bangalore. -

List of Bridges in Sikkim Under Roads & Bridges Department

LIST OF BRIDGES IN SIKKIM UNDER ROADS & BRIDGES DEPARTMENT Sl. Total Length of District Division Road Name Bridge Type No. Bridge (m) 1 East Singtam Approach road to Goshkan Dara 120.00 Cable Suspension 2 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 65.00 Cable Suspension 3 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 92.50 Major 4 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 33.00 Medium Span RC 5 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 19.00 Medium Span RC 6 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 26.00 Medium Span RC 7 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 17.00 Medium Span RC 8 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 17.00 Medium Span RC 9 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 16.00 Medium Span RC 10 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 39.00 Medium Span RC 11 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 38.00 Medium Span STL 12 East Pakyong Assam Pakyong 32.00 Medium Span STL 13 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 24.00 Medium Span STL 14 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 32.00 Medium Span STL 15 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 31.50 Medium Span STL 16 East Pakyong Pakyong-Mamring-Tareythan 40.00 Medium Span STL 17 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 9.00 Medium Span STL 18 East Singtam Duga-Pacheykhani 40.00 Medium Span STL 19 East Singtam Sangkhola-Sumin 42.00 Medium Span STL 20 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 29.00 Medium Span STL 21 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 12.00 Medium Span STL 22 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 18.00 Medium Span STL 23 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 19.00 Medium Span STL 24 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 25.00 Medium Span STL 25 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 12.00 Medium Span STL 26 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 19.00 Medium Span STL 27 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 28.00 Medium Span STL 28 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 25.00 Medium Span STL 29 East Sub - Div -IV Rumtek-Rey-Ranka 53.00 Medium Span STL Sl. -

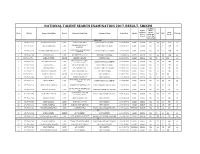

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status Residence (Please Total Sl

NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION 2017-RESULT, SIKKIM Disability Area of Status residence (please Total Sl. No. Roll No. Name of Candidates District Address of Candidates Address of School School Code Gender SAT MAT LT Marks (Rural/ verify and Marks Urban) attach the certificate) MERIT LIST 1 17170001202 INDRA BDR CHETTRI EAST PADAMCHEY EAST PADAMCHEY SEC SCHOOL 11040802902 MALE URBAN NIL 73 37 110 29 QRNO 6B /402 SUNCITY 2 17170001027 CHIRAG MARAGAL EAST ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 MALE URBAN NIL 72 37 109 37 RANIPOOL 3 17170001213 TSERING PHUNTSOK BHUTIA EAST TSHERING NORBU FL SHOP OPP/D/VILLA 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 68 40 108 43 CHANDMARI TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 4 17170001028 BHAVANA RAI EAST NO I DET ECCIU C/O 17 ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 68 37 105 39 5 17170003072 SUNIL CHETTRI SOUTH KEWZING SOUTH KEWZING SSS 11030205001 MALE RURAL NIL 72 32 104 28 ICICI ATM BLD OFF ENTEL 6 17170001210 PRANISH SHRESTHA EAST TASHI NAMGYAL ACADEMY 11040300804 MALE URBAN NIL 65 35 100 37 MOTERS TADONG 7 17170001030 RANI KUMARI EAST STN HQ NEW CANTT GTK ARMY PUBLIC SCHOOL 11040300140 FEMALE URBAN NIL 67 32 99 40 8 17170001063 ANUSHA SUNAR EAST JNV PAKYONG EAST MIDDLE CAMP SEC SCHOOL 11040604701 FEMALE RURAL NIL 57 42 99 39 9 17170001172 BISWADEEP SHARMA EAST TAKTSE BOJOGARI EAST SIR TNSS SCHOOL 11040300801 MALE RURAL NIL 60 36 96 40 10 17170003105 BANDITA CHETTRI SOUTH MELLI KERABARI SOUTH JNV RAVONGLA 11030207301 FEMALE RURAL NIL 62 33 95 41 11 17170001066 NEHAL DAS EAST RONGLI BAZAR EAST JNV PAKYONG 11040100703 MALE URBAN -

REQUEST for PROPOSAL (RFP) December, 2016

National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. (A Government of India Undertaking) CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR AUTHORITY’S ENGINEER FOR (i) Construction of 1000m length Viaduct at Rangpo between Km 51.1 0 to Km 53.90 on Sevoke - Gangtok Road NH-10 (Old NH- 31A) in the State of West Bengal/Sikkim. (ii)Construction of upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulder including geometric improvement from Km. 0.00 0to Km. 26.706 in Rhenok- Rorathang-Pakyong of NH-717A on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘Á’ in the State of Sikkim. (iii) Construction/upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulders including geometric improvement of NH-510 from Km 0.00 to Km 32.5 (Singtam-Tarku-Rabongla-Legship-Gyalshing) on EPC basis under SARDP- NE Phase ‘A’ in the State of Sikkim. REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) December, 2016 National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited 3rd Floor, Press Trust of India Building, 4, Parliament Street, New Delhi – 110001. CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR AUTHORITY’S ENGINEER FOR (i)Construction of 1000m length Viaduct at Rangpo between Km 51.1 0 to Km 53.90 on Sevoke - Gangtok Road NH-10 (Old NH- 31A) in the State of West Bengal/Sikkim.(ii)Construction of upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulder including geometric improvement from Km. 0.00 0to Km. 26.706 in Rhenok-Rorathang-Pakyong of NH-717A on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘Á’ in the State of Sikkim. (iii)Construction/upgradation of existing road to 2-lane with paved shoulders including geometric improvement of NH-510 from Km 0.00 to Km 32.5 (Singtam-Tarku-Rabongla-Legship-Gyalshing) on EPC basis under SARDP-NE Phase ‘A’ in the State of Sikkim. -

Chapter 8 Sikkim

Chapter 8 Sikkim AC Sinha Sikkim, an Indian State on the Eastern Himalayan ranges, is counted among states with Buddhist followers, which had strong cultural ties with the Tibetan region of the Peoples’ Republic of China. Because of its past feudal history, it was one of the three ‘States’ along with Nepal and Bhutan which were known as ‘the Himalayan Kingdoms’ till 1975, the year of its merger with the Indian Union. It is a small state with 2, 818 sq. m. (7, 096 sq. km.) between 27 deg. 4’ North to 28 deg 7’ North latitude between 80 deg. East 4’ and 88deg. 58’ East longitude. This 113 kilometre long and 64 kilometre wide undulating topography is located above 300 to 7,00 metres above sea level. Its known earliest settlers, the Lepchas, termed it as Neliang, the country of the caverns that gave them shelter. Bhotias, the Tibetan migrants, called it lho’mon, ‘the land of the southern (Himalayan) slop’. As rice plays important part in Buddhist rituals in Tibet, which they used to procure from India, they began calling it ‘Denjong’ (the valley of rice). Folk traditions inform us that it was also the land of mythical ‘Kiratas’ of Indian classics. The people of Kirati origin (Lepcha, Limbu, Rai and possibly Magar) used to marry among themselves in the hoary past. As the saying goes, a newly wedded Limbu bride on her arrival to her groom’s newly constructed house, exclaimed, “Su-khim” -- the new house. This word not only got currency, but also got anglicized into Sikkim (Basnet 1974). -

February 26.Pmd

SIkKIM HERAL Vol. 64 No. 10 visit us at www.ipr.sikkim.gov.in Gangtok (Friday) February 26, 2021 Regd. No.WB/SKM/01/2020-2022D CM attends foundation stone Election to Municipal bodies of Sikkim laying ceremony of various infrastructures to be held on March 31: SEC Gangtok, February 25: The State Also, she informed that the of Municipal wards under Gangtok Election Commission held a press State Government has amended Municipal Corporation has been briefing regarding the upcoming 3rd the relevant portion of the increased from 17 to 19. The newly General Municipal Election 2021 in Municipalities Act, 2007 which created wards under Gangtok the State, in the chamber of the dissolved the existing members of Municipal Corporation are State Election Commissioner, the Municipalities and deferred the Bhojoghari, 2nd Mile and Pani Tadong, today. Municipal Election for a period of House. According to the press note six months. Further, under South from State Election Commission She also informed that the District, Nayabazar- Jorethang Elections to the municipal bodies segregation and preparation of Municipal Council has been of Sikkim will be held on 31st March Municipal ward wise Electoral renamed as Nayabazar- Jorethang 2021, the results of which will be Rolls time being in force prepared Nagar Panchayat and Gyalsing declared on 3rd April, 2021. and published by the Chief Municipal Council under west Notification will be issued on 1st Electoral Officer, Sikkim in district has been renamed as March 2021 for inviting nomination Assembly Constituency wise with Gyalshing Nagar Panchayat. papers, while the last date for filing reference to 1st January 2021 as the The total number of nomination is 8th March 2021. -

Down the Ages in Sikkim

Journal of Global Literacies, Technologies, and Emerging Pedagogies Volume 5, Issue 2, December 2019, pp. 895-904 The Tsongs (Limbus) Down the Ages in Sikkim Dr. Buddhi L. Khamdhak1 Assistant Professor Department of Limboo, Sikkim Govt. College, Gyalshing, Sikkim. Abstract: The Limbus, Yakthungs or Tsongs, who have inhabited the Himalayan belt of Kanchanjanga since time immemorial, are one of the Indigenous people of Sikkim (India), Nepal, Bhutan, Burma, and Thailand. They are neither Nepalis by ethnicity nor Hindus by religion. Historically, linguistically, and culturally they have a distinct identity; however, over the centuries, they have been denied and deprived of Indigenous rights and justice. In this article, I will demonstrate the socio-cultural and linguistic conditions of Limbus in Sikkim prior, and during, the Namgyal/Chogyal reign. Then, I will argue how the Limbus were deprived of all their rights and justice in Sikkim. Keywords: Sikkim/Sukhim, Tsong, Yakthung, Lho-Men-Tsong-Sum, Chogyal, Citizenship Rights Introduction The Sikkimi Tsongs, Limbus or Yakthungs, are the Indigenous inhabitants of Sikkim. They are also commonly called “Tsong” by the Bhutias and Lepchas in Sikkim. The Limbus call themselves “Yakthung,” and they share very close historical and socio-cultural ties with 1 Dr. Buddhi L. Khamdhak is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Limboo, Sikkim Govt. College, Gyalshing, Sikkim. He can be reached at [email protected]. ISSN: 2168-1333 ©2019 Khamdhak/JOGLTEP 5(2) pp. 895-904 896 the Lepchas2 and linguistic affinity with the Bhutias3 of Sikkim. The total population of Limbus in Sikkim is 56,650, which is approximately 9.32% of the total population of the state (6,07,688 people according to the 2011 Census).