Greek Orthodox Psaltic Art: Performance And/Or Prayer?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Office of Vespers

THE PATRIARCHAL ORTHODOX CHURCH OF ROMANIA ARCHDIOCESE OF WESTERN EUROPE THE OFFICE OF VESPERS TYPIKON ( With Litiya & Artoklasia Service ) ? The priest vests with the epitrachelion in the sanctuary. He opens the curtain and the Royal Doors Standing before the holy table facing East, he blesses himself saying loudly : Priest Blessed is Our God, always, Now and Forever, and to the Ages of Ages. + Choir Amen. Glory to Thee our God, Glory to Thee. The Choir Leader begins the Trisagion Prayers. The priest closes the Holy Doors and curtain Choir Come let us worship and bow down before God our King ( + metanie ) Come let us worship and bow down before Christ, our King and God ( + metanie ) Come let us worship and bow down before Christ himself, our King, and our God ( + metanie ) O Heavenly King, the Paraclete, the Spirit of Truth, who are present everywhere filling all things, Treasury of good things, and Giver of Life, come and dwell in us, cleanse us of every stain, and save our souls, O Good One. + Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, Have mercy on us ( three times) + Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, Now, and forever, and to the Ages of Ages, Amen. All Holy Trinity have mercy on us. Lord forgive us our sins. Master pardon our transgressions. Holy One, visit and heal our infirmities for your name’s sake. Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy. + Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit Now, and forever, and to the Ages of Ages, Amen. -

June 09, 2020 Rev. Father, Hon. President, & Est. Members of the Community Council, Churches of the Greek Orthodox Archdioc

June 09, 2020 Rev. Father, Hon. President, & Est. Members of the Community Council, Churches of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Canada In Ontario Beloved in Christ, Plan for the Reopening of the Churches 1. Church leaders are responsible for the implementation and adherence to all health regulations issued by each Province. If any particular parish feels that they are not ready to implement the following guidelines immediately, they can postpone re-opening for up to a week. 2. All those in high risk groups are strongly urged to stay home in accordance with government guidelines. 3. Each Church according to its area should determine how many people it can safely host per service, while maintaining government guidelines (2 m social distancing and 30% capacity). 4. There should be more services during the week to accommodate all the faithful, or more than one (1) service will be done daily so people can attend and maintain social distancing. 5. Only one chanter per chanting station (analogion) is permitted. 6. Up to five (5) altar boys per service are permitted (depending on size of altar area) and only one sexton. 7. When full capacity of 30% is reached, no parishioners will be allowed into the Church. Additional people are free to wait outside until the end of Liturgy, maintaining social distance. Please note that Church halls can be used for additional seating, provided they do not surpass 30% of the hall’s occupancy and still maintain social distancing. When Liturgy concludes clergy have 2 options: a) After the first group exits the Church, those waiting outside may be allowed in to receive Holy Communion or b) If they are too many people, clergy can consider, or even plan beforehand, to have additional services the same day. -

St Nicholas Greek Orthodox Cathedral SUMMER COFFEE HOURS! Cordially Invites

August 1, 2017 Father’s Message Beloved Brothers and Sisters in Christ: Greetings in our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ! St. At the heart of the worship life of Orthodox Christians is the celebration of the Divine Liturgy. And at the heart of the Divine Liturgy is the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. This ritual is the most Nicholas ancient and universal in the history of our Church, going back all the way to our Lord and Savior Jesus Greek Christ, who instituted it at His last meal with His disciples before His death, called the “Mystical Supper” in our tradition. He declared the bread to be His Body, and the wine to be His Blood. We make this Orthodox miracle real again every time we repeat His words, and invoke God the Father to send down His Holy Cathedral Spirit to effect the change. How exactly this happens, our Church does not attempt to analyze; it is the “mystery” at the heart of the Mystical Supper. All we know is that it is the Lord’s ardent desire that we be united to Him and to one another not just spiritually, but also in a material, tangible way, through receiving AUGUST 2017 Holy Communion. In this manner, we are invited to experience a foretaste of God’s Kingdom already in this life, “for remission of sins and life everlasting.” Newsletter When the priest invokes the Holy Spirit, the prayer focuses on more than the bread and wine. The exact words are: “Once again we offer to you this spiritual worship without the shedding of blood, and we ask, pray, and entreat you: send down Your Holy Spirit upon us and upon these gifts here present- Points of ed.” The blessing, the sanctification is intended not just for what is in the chalice, but also on everyone Interest Inside: who is present for the worship service. -

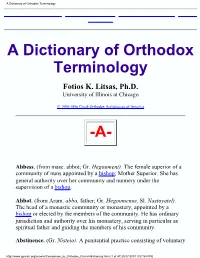

A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D

- Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Page 1 of 25 Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D. -A- Abbess. (from masc. abbot; Gr. Hegoumeni ). The female superior of a community of nuns appointed by a bishop; Mother Superior. She has general authority over her community and nunnery under the supervision of a bishop. Abbot. (from Aram. abba , father; Gr. Hegoumenos , Sl. Nastoyatel ). The head of a monastic community or monastery, appointed by a bishop or elected by the members of the community. He has ordinary jurisdiction and authority over his monastery, serving in particular as spiritual father and guiding the members of his community. Abstinence. (Gr. Nisteia ). A penitential practice consisting of voluntary deprivation of certain foods for religious reasons. In the Orthodox Church, days of abstinence are observed on Wednesdays and Fridays, or other specific periods, such as the Great Lent (see fasting). Acolyte. The follower of a priest; a person assisting the priest in church ceremonies or services. In the early Church, the acolytes were adults; today, however, his duties are performed by children (altar boys). Aër. (Sl. Vozdukh ). The largest of the three veils used for covering the paten and the chalice during or after the Eucharist. It represents the shroud of Christ. When the creed is read, the priest shakes it over the chalice, symbolizing the descent of the Holy Spirit. Affinity. (Gr. Syngeneia ). The spiritual relationship existing between an individual and his spouse’s relatives, or most especially between godparents and godchildren. The Orthodox Church considers affinity an impediment to marriage. -

St. George Orthodox Church Live Streaming of Divine Services

St. George Orthodox Church V. Rev. Father Joseph M. Abud, Pastor 5191 Lennon Road • Flint, MI 48507 • (810) 732-0720 Protodeacon Michael Bassett Web Site: saintgeorgeflint.org June 14, 2020 أحد جميع القديسين 1ST SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST ~ ALL SAINTS Tone 8 1st Matins Gospel {Matthew 28:16-20} Confessions Matins p.44 Divine Liturgy p.91 Memorial Service 8:30-9:30am 8:50am 10:00am Trisagion p.183 Live Streaming of Divine Services ALL services are served only with clergy, an altar server, and a few chanters. They are not open to the public. Please view our livestream at: YouTube ~ https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpLWfxMIJK4uQOV41ekE6Wg or Facebook ~ https://www.facebook.com/St-George-Flint-254638524560302/ If you have a smart TV, you actually have a web browser and YouTube app built in. All you have to do is start the browser app for YouTube and put the link in the address bar. In the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom {the Golden-Mouth}, The Special Hymns we sing are on the Bilingual sheets from Fr. Joe’s Email). Holy Bread Offerings Protodeacon Michael and Pam Bassett for the health of their family and in loving memory of Edgar Parsons (9 day) and Joseph Papanek (9 day, both are friends of Dn. Mike). Fares and Sahar Abdallah and Dr. George and Cindy Zureikat and their families for the health of their families and in loving memory of Yacoub Zureikat (40 day, father of Sahar and Dr. George). Baptism/Chrismation Days The Church School offers the Holy Bread for their teachers and/or students who celebrated their New Birth {Baptism and/or Chrismation} into the Church this past week: Isabella Ibrahim and Christina Rishmawi – June 20th May our children be children of the Light and heirs of eternal good things. -

The Amomos in the Byzantine Chant: a Diachronical Approach with Emphasis on Musical Settings of the 19Th and 20Th Centuries

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2018-0002 Artes. Journal of Musicology no. 17-18 2018 24-73 The Amomos in the Byzantine chant: a diachronical approach with emphasis th th on musical settings of the 19 and 20 centuries DIMOS PAPATZALAKIS Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Greece∗ Abstract: The book of the Psalms constitutes the main source from where the Offices of the Orthodox church draw their stable parts. It has been diachronically one of the most used liturgical books of the cathedral and the monastic rite. In this paper we focus on the Psalm 118, which is well known under the designation “Amomos”. In the first part of our study we look for the origin of the book of the Psalms generally. Afterwards we present the Offices in which the Amomos is included, starting from the Byzantine era and the use of the Amomos in the cathedral and the monastic services. Then, we negotiate the question of its use in the post-Byzantine era. In the next section we quote the most important settings of the Byzantine, post-Byzantine and new- Byzantine composers in Constantinople, Smyrna and Thessaloniki, as well as some evidence of their lives and their musical works. In the next section we introduce some polyprismatic analyses for the verses of the first stanza of the Amomos, which are set to music in 19th and 20th centuries. After some comparative musicological analyses of the microform of the compositions or interpretations, we comment on the music structure of the settings of Amomos in their liturgical context. Our study concludes with some main observations, as well as a list of the basic sources used to write this paper. -

A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology

A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D. University of Illinois at Chicago © 1990-1996 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America -A- Abbess. (from masc. abbot; Gr. Hegoumeni). The female superior of a community of nuns appointed by a bishop; Mother Superior. She has general authority over her community and nunnery under the supervision of a bishop. Abbot. (from Aram. abba, father; Gr. Hegoumenos, Sl. Nastoyatel). The head of a monastic community or monastery, appointed by a bishop or elected by the members of the community. He has ordinary jurisdiction and authority over his monastery, serving in particular as spiritual father and guiding the members of his community. Abstinence. (Gr. Nisteia). A penitential practice consisting of voluntary http://www.goarch.org/access/Companion_to_Orthodox_Church/dictionary.html (1 of 47) [9/27/2001 3:51:58 PM] A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology deprivation of certain foods for religious reasons. In the Orthodox Church, days of abstinence are observed on Wednesdays and Fridays, or other specific periods, such as the Great Lent (see fasting). Acolyte. The follower of a priest; a person assisting the priest in church ceremonies or services. In the early Church, the acolytes were adults; today, however, his duties are performed by children (altar boys). Aër. (Sl. Vozdukh). The largest of the three veils used for covering the paten and the chalice during or after the Eucharist. It represents the shroud of Christ. When the creed is read, the priest shakes it over the chalice, symbolizing the descent of the Holy Spirit. Affinity. (Gr. -

Dictionary of Religious Terms

IMPORTANT INFORMATION – Please Read! his lexicon began as a personal project to assist me in my efforts to learn more about my faith. All too often in my T readings I was coming across unfamiliar words, frequently in languages other than English. I began compiling a “small” list of terms and explanations to use as a reference. Since I was putting this together for my own use I usually copied explanations word for word, occasionally making a few modifications. As the list grew I began having trouble filling in some gaps. I turned to some friends for help. They in turn suggested this lexicon would be a good resource for the members of the Typikon and Ustav lists @yahoogroups.com and that list members maybe willing to help fill the gaps and sort out some other trouble spots. So, I present to you my lexicon. Here are some details: This draft version, as of 19 December 2001, contains 418 entries; Terms are given in transliterated Greek, Greek, Old Slavonic, Ukrainian, and English, followed by definitions/explanations; The terms are sorted alphabetically by “English”; The Greek transliteration is inconsistent as my sources use different systems; This document was created with MS Word 97 and converted to pdf with Adobe Acrobat 5.0 (can be opened with Acrobat Reader 4.0); Times New Roman is used for all texts except the Old Slavonic entries for which I used a font called IZHITSA; My sources are listed at the end of the lexicon; Permission has not been obtained from the authors so I ask that this lexicon remain for private use only. -

Grammenos Karanos), Dormition of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church, Somerville, MA, March 2016

REV. DR. ROMANOS (GRAMMENOS) KARANOS 76 Gerry Road, Brookline, MA 02467-3138 Telephone: 617-850-1236 E-mail: [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Last updated January 26, 2021 Education National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece School of Philosophy, Department of Musical Studies • Ph.D. in Byzantine Musicology and Psaltic Art (2011) • Dissertation: Τὸ Καλοφωνικὸν Εἱρμολόγιον [The Kalophonic Heirmologion] • Advisors: Gregorios Stathis, Achilleus Chaldaeakes, Demetrios Balageorgos Boston University, Boston, MA Graduate School of Management • Master of Business Administration (2004) Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Harvard-Radcliffe Colleges • Bachelor of Arts cum laude in Government (1997) • Senior Thesis: The Concept of Moderation in the Theories of Plato and Aristotle • Advisor: Petr Lom Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Boston, Boston, MA School of Byzantine Music • Certificate of Byzantine Music with highest distinction (2002) • Studied under Professor Photios Ketsetzis, Archon Protopsaltis of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Teaching Experience / Appointments Hellenic College/Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, Brookline, MA Assistant Professor of Byzantine Liturgical Music (September 2011 – present) Mathimata, Kratimata, and Deinai Theseis The Kalophonic Heirmologion History of Western Music History of Byzantine Music Directed Study in Byzantine Chant to American Sign Language Directed Study in Byzantine Music Instruction for Beginners Directed Study in Advanced Ecclesiastical Composition in English Service Rubrics Byzantine Music for Clergy Byzantine Music X – Papadike, Old Sticherarion, and Kalophonic Heirmoi CV of Fr. Romanos Karanos Byzantine Music IX – Papadike and Old Sticherarion Byzantine Music VIII – Divine Liturgy Byzantine Music VII – Doxastarion & Slow Heirmologion Byzantine Music VI – Holy Week Byzantine Music V – Prosomoia and Music for Sacraments Byzantine Music IV – Anastasimatarion: Modes II, Pl. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lingas, A. ORCID: 0000-0003-0083-3347 (2008). The Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom according to the Byzantine Tradition: A New Musical Setting in English. Portland, USA: Cappella Romana. This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/21533/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CAPPELLA ROMANA THE DIVINE LITURGY OF OUR FATHER AMONG THE SAINTS JOHN CHRYSOSTOM IN ENGLISH IN BYZANTINE CHANT 2 CDS: THE COMPLETE SERVICE the DIVINE LITURGY • CAPPella Romana The Very Revd Archimandrite Meletios (Webber), priest · The Revd Dr John Chryssavgis, deacon DISC ONE: the LITURGY DISC TWO: the LITURGY of the CATECHUMENS 46:55 of the FAITHFUL 60:5 Opening Blessing, Litany of Peace, Cherubic Hymn in Mode Plagal IV, after and Prayer of the First Antiphon 5:4 Petros Peloponnesios (d. -

“I Understood God Was Pulling Me in a Different Direction.”

SPRING 2018 DOXA! The newsletter for supporters and GLORY friends of Hellenic College Holy Cross “I understood God was pulling me in a different direction.” that builds homes The third year of seminary is a very busy one for every for the poor student, but especially for John Tsikalas, who is currently and operates serving as HCHC’s Ecclesiarch. To be chosen for such St. Innocent an important position by the Dean of Students and the Orphanage for President is a great honor—and a great responsibility. young boys. John As the word indicates, an Ecclesiarch is in charge of a logged over a church, which at HCHC means Holy Cross Chapel. In thousand hours that role, John ensures that the Chapel is always properly of community prepared and staffed for the many services that take place service in Mexico, there. With the help of assistant Ecclesiarch and classmate and “after the Nicholas Mataragas, John oversees a team of fellow Holy third summer, Cross students who perform various essential functions, I was clear that from maintaining the Chapel and the precious liturgical I didn’t want vessels to baking prosforo—all to ensure the purity of to go to law worship in that sacred space. school. The hard work, An exemplary student, liked and respected by everyone on deep friendships, and authentic joy I experienced in campus, John would appear to be a natural for the job, but Mexico led me to believe that Christ was calling me to not so long ago he was unsure about entering seminary at serve the Church as a priest…While I was—and still all. -

Cleaning the Church Holy Resurrection Orthodox Church

Cleaning the Church Holy Resurrection Orthodox Church How pleasant it is to come into the church and find enter the Altar at any time. it clean and in good order. It shows that we, as a Supplies: Everything you need should be available congregation, care about how we approach God, in the janitors closet accessible through the beige that we love one another and that we have respect curtain to the south of the iconostasis. Both men for our visitors. We must rely on one another to and women may enter this area. If we are out of fulfill God’s work in our parish. When we take the supplies, please check with Rdr. Bede or Keith time to do work for the church - be it cleaning or Hoirup. gardening, teaching or singing, we are are truly participating in the “physical side of being Dust for Cobwebs: There is an extendible cobweb spiritual.” The reward that we receive for this is not duster in the janitors closet. Use it along corners of just a “thank you” from the priest, who is ever the walls and ceilings, over the iconostasis, the chandelier, banner tops, recessed lights, etc. grateful for the work you do, but rather the “Well done, good and faithful servant; you have been Clean Window & Kneewall Sills: Dust them with faithful over a little, I will set you over much; enter a paper towel. into the joy of your Master.” (Mat 25:23) that we Remove Candles: Hopefully, the Handmaidens hope to hear in the life to come. will have taken care of this.