Officers' Uniforms and Gear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineers Week Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials

Engineers Week Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials Classroom Resource Booklet Developed for 1 Engineers Week - Classroom Resource Booklet DPSM/ESERO Framework for Inquiry THEME Overall theme Strand: CURRICULUM Maths: Strand Unit: Curriculum Objectives: Skills Development: Considerations ENGAGE for inclusion THE TRIGGER WONDERING EXPLORING INVESTIGATE CONDUCTING THE SHARING: INTERPRETING STARTER QUESTION PREDICTING INVESTIGATION THE DATA / RESULTS TAKE THE NEXT STEP APPLYING LEARNING MAKING CONNECTIONS THOUGHTFUL ACTIONS REFLECTION 2 Engineers Week - Classroom Resource Booklet DPSM/ESERO Framework for Inquiry THEME ENGINEERS WEEK 2021 – ENGINEERING DESIGN Strand: Living Things, Materials; Energy and Forces; Environmental Awareness and Care. Strand Unit: Human Life, Properties and Characteristics of Materials. CURRICULUM Curriculum Objectives: Explore and investigate how people move; Understand how materials may be used in construction; Explore the effect of friction on movement through experimenting with toys and objects on various surfaces. Skills Development - Working Scientifically: Questioning, Observing, Predicting, Analysing, Investigating, Recording and Communicating; Design, plan and carry out simple investigations; Designing and Making: Exploring, Planning, Making, Evaluating; Work collaboratively to create a design proposal; Communicate and evaluate the design plan using sketches, models and information and communication technologies; Using small models and/or sketches showing measurements and materials required; -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 087 919 CB 001 018 AUTHOR Hayes, Philip TITLE Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C. Vocational Education Media Center.; South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. Office of Vocational Education. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 100p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$4.20 DESCRIPTORS Business Education; Clothing Design; *Distributive Education; *Guides; High School Curriculum; Manuals; Student Developed Materials; *Student Projects IDENTIFIERS *Career Awareness; South Carolina ABSTRACT This semester-length guide for high school distributive education students is geared to start the student thinking about the vocation he would like to enter by exploring one area of interest in marketing and distribution and then presenting the results in a research paper known as an area of distribution manual. The first 25 pages of this document pertain to procedures to follow in writing a manual, rules for entering manuals in national Distributive Education Clubs of America competition, and some summary sheet examples of State winners that were entered at the 25th National DECA Leadership Conference. The remaining 75 pages are an example of an area of distribution manual on "How Fashion Changes Relate to Fashion Designing As a Career," which was a State winner and also a national finalist. In the example manual, the importance of fashion in the economy, the large role fashion plays in the clothing industry, the fast change as well as the repeating of fashion, qualifications for leadership and entry into the fashion world, and techniques of fabric and color selection are all included to create a comprehensive picture of past, present, and future fashion trends. -

The Denim Report

118 Fashion Forward Trends spring/summer 2016 | fabrics & more | FFT magazine 119 THE DENIM REPORT n this season, the denim offering is wide and qualitative: selvedge denim for purists, power stretch for trendsetters, washed-out effect for the 70s wind blowing around Ithe fashion world, and eco-friendly for green and ethical brands. Little did one know that the fabric would ingratiate itself in the mainstream so decidedly as to become the uniform of generations post the 80s. Irrespective of whether you belong in the 1% or the 99, your age bracket or your cultivated tastes, denim has been part of everyone’s wardrobe. It’s a 60 billion dollar market for retailers alone and designers are keen to partake a piece of this massive pie. It helps that the fabric is the ‘people pleaser’ – it will readily turn into anything one likes. Numerous innovations and fabric infusions such as khadi-denim, silk- denim, 3D textures and laser and ozone finishes change its face beyond comprehension, and this, once street-style, turns sophisticated enough to form a cocktail dress. INDUSTRY TRENDS Sustainability has been a long-standing buzzword but there is ever-newer growth in this direction. As the trend for distressed jeans diminishes, the dyeing process becomes less dependent on chemical sprays and resins. Multiple brands are opting to use 100% organic cotton and natural dye. Artisanal products go for untreated metal zippers and rivets, making it non-toxic. Chemical companies’ enthusiasm for change is making them to associate with leading jeans manufacturers to bring about major savings in key materials, energy, water usage, waste and emission reductions, and ensuring your right to operate in communities around the world. -

An Eden with No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in The

An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Joshua Gibbons Striker 2019 Abstract In this dissertation I use an old and unfashionable form of literary criticism, close reading, to offer a new and unfashionable account of the literary subgenre called camp. Drawing on the work of, among many others, Susan Sontag, Rita Felski, and Peter Lamarque, I argue that P.G. Wodehouse, E.F. Benson, and Angela Thirkell wrote a type of pure comedy I call chaste camp. Chaste camp is a strange beast. On the one hand it is a sort of children’s literature written for and about adults; on the other hand it rises to a level of literary merit that children’s books, even the best of them, cannot hope to reach. -

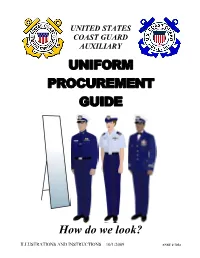

Uniform Procurement Guide

UNITED STATES COAST GUARD AUXILIARY UNIFORM PROCUREMENT GUIDE How do we look? ILLUSTRATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS – 10/1/2009 ANSC # 7053 RECORD OF CHANGES # DATE CHANGE PAGE 1. Insert “USCG AUXILIARY TUNIC OVERBLOUSE” information page with size chart. 19 2. Insert the Tunic order form page. 20 3. Replace phone and fax numbers with “TOLL FREE: (800) 296-9690 FAX: (877) 296-9690 and 26 1 7/2006 PHONE: (636) 685-1000”. Insert the text “ALL WEATHER PARKA I” above the image of the AWP. 4. Insert the NEW ALL WEATHER II OUTERWEAR SYSTEM information page. 27 5. Insert the RECEIPT FOR CLOTHING AND SMALL STORES form page. 28 1. Insert additional All Weather Parka I information. 26 2 11/2006 2. Insert All Weather Parka II picture. 27 1. Replace pages 14-17 with updated information. 14-17 3 3/2007 2. Insert UDC Standard Order Form 18 1. Change ODU Unisex shoes to “Safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes***” 4 4/2007 6, 8 2. Add a footnote for safety boots, low top shoes, or boat shoes 5 2/2008 1. Remove ODU from Lighthouse Uniform Company Inventory 25 1. Reefer and overcoat eliminated as outerwear but can be worn until unserviceable 6-10 6 3/2008 2. Remove PFD from the list of uniform items that may be worn informally 19 3. Update description of USCG Auxiliary Tunic Over Blouse Option for Women 21 1. Remove “Long”, “Alpha” and “Bravo” terminology from Tropical Blue and Service Dress Blue 7 6/4/2009 All uniforms 1. Sew on vendors for purchase of new Black “A” and Aux Op authorized 32 8 10/2009 2. -

AUTOMOTIVE MANAGEMENT June 2018 £8.00

AUTOMOTIVE MANAGEMENT www.am-online.com June 2018 £8.00 NEW MOT RULES / P6 Tougher test may boost workshop volumes SUBARU / P34 We have turned a corner, says MD Chris Graham DIGITAL DEALER / P41 Technology to help you in new sales, used sales and aftersales STEPHEN BRIGHTON – HEPWORTH MOTOR GROUP / P24 ‘WE WANT TO GROW, BUT NOT AT ANY COST’ adRocket Using the iConsent module, on average customers select the following marketing options: FP_AM_Advert1605id3486601.pdf 16.05.2018 15:56 EDITOR’S LETTER he label ‘Made in Germany’ has long been regarded as a stamp of quality, given the country’s reputation for engineering and attention to detail. However, it seems that ‘Decided by Germany’ is becoming a painful reality for some UK franchised dealers. BMW has received a public thrashing during an inquest into a fatal car crash in the early hours of Christmas Day, 2016. Woking Coroner’s Court heard that the crash occurred after Narayan Gurung, a former Gurkha in his 60s, swerved to avoid an unlit BMW, which had broken down on a major road. T It emerged at the inquest that BMW had known about an electrical fault that caused some cars to stall and lose their lights since 2011. It had recalled vehicles in some other countries, but not in the UK. Shamefully, it did not recall them until after Gurung’s death. Even then, it recalled 36,410 cars, fewer than 10% of the number the DVSA asked for. BMW UK was unable to explain the delay at the inquest, except to say that recall “decisions are made in Germany” and the fault was not considered “critical”. -

Price List Best Cleaners 03-18.Xlsx

Price List Pants, Skirts & Suits Shirts & Blouses Pants Plain…………………………………………… 10.20 Business Shirt Laundered and Machine Pants, Silk/Linen…………………………………… . 12.30 Pressed (Men’s & Women’s)…… 3.60 Pants, Rayon/Velvet………………………………… 11.80 Pants Shorts………………………………………. 10.20 Chamois Shirt…………………………………………… 5.35 Skirts, Plain………………………………………… . 10.20 Lab Smock, Karate Top………………………………… . 7.30 Skirts, Silk, Linen………………………………….. 12.30 Polo, Flannel Shirt……………………………………… .. 5.35 Skirts, Rayon Velvet……………………………… .. 11.80 Sweat Shirt……………………………………………… . 5.70 Skirts Fully Pleated………………………………. 20.95 T-Shirt…………………………………………………… .. 4.60 Skirts Accordion Pleated………………………… . 20.95 Tuxedo Shirt……………………………………………… . 6.10 Suit 2 pc. (Pants or Skirt and Blazer)……………… 22.40.. Wool Shirt………………………………………………… . 5.35 Suit 3 pc. (Pants or Skirt Blazer & Vest)……………… 27.75. Suit, body suit………………………………………… 10.60. Blouse/Shirt, Cotton, Poly…………………………………… 9.50.. Suit, Jumpsuit…………………………………… 25.10 Blouse/Shirt, Rayon, Velvet………………………………… 11.10.. Sport Jacket, Blazer……………………………… .. 12.20 Blouse/Shirt, Silk, Linen……………………………………… 11.60 Tuxedo……………………………………………… . 22.95 Blouse/Shirt, Sleeveless……………………………………… 7.80 Vest………………………………………………… . 5.35 Dresses Outerwear Dress, Plain, Cotton, Wool, Poly, Terry, Denim…….. 19.00 Blazer, Sport Jacket……………………………… . 12.20 Dress,Silk, Linen …….………………………………. 23.20 Bomber Jacket………………………………….. 16.20 Dress,Rayon,Velvet …………………………………. 22.20 Canvas Field Coat………………………………… 16.20 Dress, 2-Piece, Dress & Sleeveless Jkt……………………… 27.60 Canvas Barn Jacket……………………………… -

Interview with Walter Ade # VRK-A-L-2007-004 Interview # 1: May 21, 2007 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Walter Ade # VRK-A-L-2007-004 Interview # 1: May 21, 2007 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 DePue: My name is Mark DePue. I’m Director of Oral History at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. Today is Monday, May 21st, and I’m here with Walter Ade, a veteran of the Korean War who was with the 5th Regimental Combat Team at the end of the Korean War. Walter, just from what you and I have spoken about before, I know you have a lot of fascinating and important stories to tell. We are here at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. That’s where we’re conducting the interview. And this is part of the library’s Veterans Remember oral history project. So Walter, what I would like to do is to start with a little bit about your background, where you were born and when you were born. Let’s start with that. Ade: I was born on the 3rd of October, 1931 in Bruchsal. Bruchsal is a town in the state of Wurttemberg-Baden between Heidelberg and Karlsruhe on State Route B3. -

The Developing Years 1932-1970

National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNIFORMS The Developing Years 1932-1970 Number 5 By R. Bryce Workman 1998 A Publication of the National Park Service History Collection Office of Library, Archives and Graphics Research Harpers Ferry Center Harpers Ferry, WV TABLE OF CONTENTS nps-uniforms/5/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016 http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-uniforms/5/index.htm[8/30/18, 3:05:33 PM] National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 (Introduction) National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 INTRODUCTION The first few decades after the founding of America's system of national parks were spent by the men working in those parks first in search of an identity, then after the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 in ironing out the wrinkles in their new uniform regulations, as well as those of the new bureau. The process of fine tuning the uniform regulations to accommodate the various functions of the park ranger began in the 1930s. Until then there was only one uniform and the main focus seemed to be in trying to differentiate between the officers and the lowly rangers. The former were authorized to have their uniforms made of finer material (Elastique versus heavy wool for the ranger), and extraneous decorations of all kinds were hung on the coat to distinguish one from the other. The ranger's uniform was used for all functions where recognition was desirable: dress; patrol (when the possibility of contact with the public existed), and various other duties, such as firefighting. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat.