`The Landscape' – North Wootton, South Wootton and Castle Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

2010-02 Autumn Issue

0 1 Contents page Editorial 2 Officers' Reports Chairman 3 - 4 Secretary 5 Obituary Alan Pearcey 6 Special Interest Groups Mondays 7 - 11 Tuesdays 12 - 14 Wednesdays 14 - 16 Thursdays 17 - 19 Fridays 19 - 20 Sundays 21 Visits 22 - 24 Talks 24 Miscellaneous 25 – 26 Committee 27 2 Editorial Ann and I only moved to King's Lynn in March last year but we are by no means strangers to the area. You could say our roots are in the Fens; each born and raised no more than an hour's drive from here. In our careers we moved about the country but spent the majority of our working life at Lowestoft before retiring to northern France in 1994. Joining U3A, amongst other societies and groups, was part of a strategy for integrating, but editing the newsletter could have been over-ambitious. In fact we have found support with Penny Dossetor as coordinator, and more recently have been joined by Edward and Judith Harrison. In a way this edition mirrors our experience in discovering U3A. I found that the nature and status of U3A was not well known in the town. The brief statement from the official web-site is (may I say?) rather daunting: U3As are self-help, self-managed lifelong learning co- operatives for older people no longer in full time work, providing opportunities for their members to share learning experiences in a wide range of interest groups and to pursue learning not for qualifications, but for fun. Our experience is that the King's Lynn U3A is an organisation which is varied and welcoming, catering for an eclectic range of interests and activities. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

New Electoral Arrangements for King's Lynn and West Norfolk Borough

New electoral arrangements for King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council Final recommendations April 2018 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] © The Local Government Boundary Commission for England 2018 The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2018 Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Who we are and what we do .................................................................................. 1 Electoral review ...................................................................................................... 1 Why King’s Lynn & West Norfolk? .......................................................................... 1 Our proposals for King’s Lynn & West Norfolk ........................................................ 1 What is the Local Government Boundary Commission for England? ......................... 2 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 What is an electoral review? .................................................................................. -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Chapter 3: the Finds

Chapter 3: The Finds THE MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL A draft report on the pottery from the 1984 POTTERY (FIGS 3.1-11) excavations was written by Maureen Mellor in the by Cathy Keevill 1980s. The primary aim of the further analysis was to refine the site chronology and to understand the Summary development of the site. This involved adding in the An assemblage of 6779 sherds was recovered from pottery recovered from the 1988-1991 excavations, stratified contexts. The majority of these (a total of amending the context dates derived from the assoc 6317 or 93%) were medieval. This is the first iated pottery where necessary, and checking on the stratified sequence from Witney and as such is dating for the main types within the assemblage in highly important for the understanding of the order to establish a chronology that would corres development of 12th-century and early-13th-century pond to the Oxfordshire pottery sequence. Under pottery traditions in West Oxfordshire. The most standing the development of the major local fabric interesting feature of the assemblage was the range and vessel traditions in west Oxfordshire was also a of imported material from other regions, particularly priority, especially the calcareous gravel-tempered south-western England. These included fabric types fabric (Witney Fabric 1), which is similar to types in from Minety, Wiltshire (Fabrics 9 and 37), from the Cotswolds (Mellor 1994,72) and at Oxford (fabric Laverstock, south Wiltshire (Fabrics 5 and 25), types OXAC). known in Bath and Trowbridge (fabric 23), Newbury The analysis also included a consideration of the (Fabrics 2 and 3), Winchester (Fabric 8), and a status of the site (and of different areas within the possible Nash Hill product (Fabric 33). -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

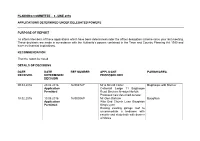

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

Proposals to Spend £1.5M of Additional Funding from Norfolk County Council

App 1 Proposals to spend £1.5m of additional funding from Norfolk County Council District Area Road Number Parish Road Name Location Type of Work Estimated cost Breckland South B1111 Harling Various HGV Cell Review Feasibility £10,000 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road near recycle centre Resurfacing 8,164 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road on bend o/s Church Resurfacing 14,333 Breckland West 33261 Hilborough Coldharbour Lane nearer Gooderstone end Patching 23,153 Breckland West C116 Holme Hale Station Road jnc with Hale Rd Resurfacing 13,125 Breckland West B1108 Little Cressingham Brandon Road from 30/60 to end of ind. Est. Resurfacing 24,990 Breckland West 30401 Thetford Kings Street section in front of Kings Houseresurface Resurface 21,000 Breckland West 30603 Thetford Mackenzie Road near close Drainage 5,775 £120,539 Broadland East C441 Blofield Woodbastwick Road Blofield Heath - Phase 2 extension Drainage £15,000 Broadland East C874 Woodbastwick Plumstead Road Through the Shearwater Bends Resurfacing £48,878 Broadland North C593 Aylsham Blickling Road Blickling Road Patching £10,000 Broadland North C494 Aylsham Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Patching £15,000 Broadland North 57120 Aylsham Hungate Street Hungate Street Drainage £10,000 Broadland North 57099 Brampton Oxnead Lane Oxnead Lane Patching £5,000 Broadland North C245 Buxton the street the street Patching £5,000 Broadland North 57120 Horsford Mill lane Mill lane Drainage £5,000 Broadland North 57508 Spixworth Park Road Park Road Drainage £5,000 Broadland -

North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain

Sheet 24 7000 1900 4500 9100 Adopted King’s Lynn & West Norfolk Local Plan 1998 3400 Marsh Common Inset 33 Drain 0004 5.2m North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain Dismantled Railway Drain Wootton Carr Drain Drain 7887 Drain This Map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk. LA086045. 1999. Maps produced by Lovell Johns Ltd., Oxford. England. SCALE 1:5000 Track Valerian Drain Cattle Grid Drain Playing Field Drain Drain Club Track The Old Gatehouse Drain Pavilion 5572 Greenacres Drain Marsh Common Drain Pond Drain MARSH ROAD GATEHOUSE LANE 0065 3.7m AONB 3 1061 Drain Seacroft 7659 1 York House 2 CLOSE Drain Pond 1 Honeysuckle Cottage FREDERICK 6 BM 11.80m 4157 The Pinfold The Green 2356 The Green 11.3m 5456 11.9m Ponds LING COMMON LANE Glenhaven 1 Drain Dunster School 16 18 Drain Farm 0153 17 Ling Common Drain RECTORYCLOSE Pond AONB Nordean OLD The Old Rectory Dalliance The Old School Red Roofs 12 North Wootton 11.6m Drain Innisfree Tyla BM 12.94m Drain Lingwood House on the Green Winder 4 (PH) Laguegua Berleen 5 Chalet House 245 15 Wootton Carr 14 House On The Drain Rowan House Berleen Green LING COMMON ROAD 19.2m Drain 10 (PH) TCB 6 8 Woodside 14.9m 0047 Rectory Cottage 4 LING COMMON ROAD Pond PO El Sub Sta Orchard Lodge 21 BM 10.61m SANDRINGHAM 26 12 25 13 1 CRESCENT -

KING's LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014

KING'S LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014 Contractor ref: NG/25382/4 NG37 Setchey, Bridge Layby 804 1542 Setchey, Church 805 1541 Setchey, A10 Garage 806 1540 West Winch, A10 opp The Mill 810 1534 West Winch, A10 ESSO Garage 812 1532 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25372/4 NG38 Blackborough End, Bus Shelter 750 1540 Middleton, School Road 752 1538 North Runcton, New Road Post Box 755 1535 West Winch, Coronation Avenue 757 1533 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 800 1530 West Winch, Hall Lane, junction of Eller Drive 802 1528 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Laurel Grove 804 1526 West Winch, Back Lane / Common Close 805 1525 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 820 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25371/4 NG39 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 803 1542 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Eller Avenue 806 1540 West Winch, Long Lane / Hall Lane phone box 808 1538 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: EG/19968/1 EG 1 Gayton Thorpe, Phone Box 805 1610 Gayton, opp The Crown 810 1605 Gayton, Lynn Road / Winch Road 816 1559 Gayton, Lynn Road / Whitehouse Service Station 818 1557 Ashwicken, B1145 / Well Hall Lane 821 1554 Ashwicken, B1145 / Pott Row Turn 823 1552 Ashwicken, B1145 / East Winch Road 825 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 840 1535 Contractor ref: NG/19970/1 NG 3 Wolferton, Friar Marcus Stud 757 1609 Wolferton, Village Sign 758 1610 Sandringham, Gardens 804 1603 West Newton, Bus Shelter 807 1600 Castle Rising, Bus Stop 813 1554 North Wootton, Bus Shelter 817 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 835 1535 @ CONNECTS WITH BUS TO/FROM CONGHAM Contractor ref: Flitcham, Fruit Farm 748 1624 Congham, Manor Farm 758 1614 .. -

Settlement Hierarchy the Introduction to the Borough Set out in a Previous

Settlement Hierarchy The introduction to the borough set out in a previous chapter outlines some of the issues arising from its rural nature i.e. the abundance of small villages and the difficulties in ensuring connectivity and accessibility to local services and facilities. The Plan also imposes a requirement to define the approach to development within other towns and in the rural areas to increase their economic and social sustainability. This improvement will be achieved through measures that: a. support urban and rural renaissance; b. secure appropriate amounts of new housing, including affordable housing, local employment and other facilities; and c. improve accessibility, including through public transport. Consequently, it is necessary to consider the potential of the main centres, which provide key services, to accommodate local housing, town centre uses and employment needs in a manner that is both accessible, sustainable and sympathetic to local character. Elsewhere within the rural areas there may be less opportunity to provide new development in this manner. Nevertheless, support may be required to maintain and improve the relationships within and between settlements that add to the quality of life of those who live and work there. Matters for consideration include the: a. viability of agriculture and other economic activities; b. diversification of the economy; c. sustainability of local services; and d. provision of housing for local needs. Policy LP02 Settlement Hierarchy (Strategic Policy) 1. The settlement hierarchy ranks settlements according to their size, range of services/facilities and their possible capacity for growth. As such, it serves as an essential tool in helping to ensure that: a.