Babingley Catchment Outreach Report-NGP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer Shop Beer Shop

1 3 10 11 13 14 West Norfolk C5 E3 C4 C3 Sandringham House C2 C3 VISIT BRITAIN’S BIGGEST BEER SHOP & What To Do 2016 Plus WINE AND SPIRIT WWAREHOUSEAREHOUSE Sandringham House, the Royal Family’s country retreat, ATTRACTIONS is perhaps the most famous stately home in Norfolk - and certainly one of the most beautiful. The Coffee Shop at Thaxters Garden Centre is PLACES TO VISIT Opens Easter 2016 Set in 60 acres of stunning gardens, with a fascinating renowned locally for its own home-made cakes museum of Royal vehicles and mementos, the principal and scones baked daily. Its menu ranges from the EVENTS ground floor apartments with their charming collections popular cooked breakfast to sandwiches, baguettes YOUYOU DON’TDON’T HAVEHAVE Visit King’s Lynn’s of porcelain, jade, furniture and family portraits are open throughout West Norfolk and our homemade specials of the day. During the stunning new to the public. Visitor Centre open every day all year. warmer months there is an attractive garden when TOTO TRAVELTRAVEL THETHE attraction, which Open daily 26 March- 30 October you can sit and enjoy lunch and coffee. EXCEPT Wednesday 27 July. tells the stories of the Take a stroll around the attractive Garden Centre. Adults £14.00, Seniors £12.50, Children £7.00 GLOBEGLOBE TOTO ENJOYENJOY seafarers, explorers, Family (2 adults + 3 children) £35.00 It sells everything the garden could need as well as merchants, mayors, www.sandringhamestate.co.uk a large range of giftware. WORLDWORLD BEERS.BEERS.BEERS. magistrates and If you are staying in self-catering accommodation 4 North Brink, Wisbech, PE13 1LW 12 or a caravan there is a well stocked grocery store Tel: 01945 583160 miscreants who have A5 www.elgoods-brewery.co.uk C4 on site that sells hot chickens from its rotisserie, It is just a short haul to shaped King’s Lynn, one of freshly baked bread, newspapers, lottery and England’s most important everything you could possibly need. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

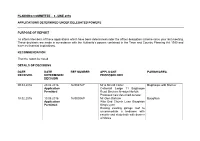

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE of REPORT to Inform Members of Th

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 24.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01172/F Mr Ian-Robert Bercham Barton Bendish Application Holly House Fincham Road Barton Permitted Bendish King's Lynn To provide a link corridor (Enclosed) between existing victorian conservatory and the out building. 27.05.2016 01.08.2016 16/01014/O Mr Geoff Simmons Bircham Application Whitegates Lynn Road Great Refused Bircham King's Lynn Outline Application: construction of a dwelling 05.05.2016 04.08.2016 16/00856/F Mr P Youel Boughton Application Kingston House Chapel Road Permitted Boughton Norfolk Single storey rear extension to dwelling 03.06.2016 21.07.2016 16/01040/F Mr & Mrs T Scrivener Boughton Application Church Farm Barn The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Construction of domestic garage 24.06.2016 18.08.2016 16/01175/F Mr & Mrs I Davis Boughton Application Hall Farm Cottage Mill Hill Road Permitted Boughton King's Lynn External wall insultation and render facing to exposed original cottage walls 10.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01095/F Mr Tim Williams Brancaster Application Bramble -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, Sora JULY 1982 10039

THE LONDON GAZETTE, SOra JULY 1982 10039 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL The Order becomes operative from 17th August 1982 but if a person aggrieved by the Order desires to question NOTICE OF CONFIRMATION OF PUBLIC PATH ORDERS the validity thereof, or of any provision contained therein, on the ground that it is not within the powers of the HIGHWAYS ACT 1959 Highways Act 1980 or any regulation made thereunder has not been complied with in relation to the Order, he may COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1968 under Schedule 2 of the Act as applied by paragraph 5 of The Kent County Council (F.P. 294 (Part) (Brabourne Schedule 6 to the Act within 6 weeks from 30th July 1982 Public Path Diversion Order 1976 make application for the purpose to the High Court. W. G. Hopkin, County Secretary The Kent County Council (F.P. 295 (Part) (Mersham) County Hall, Public Path Diversion Order 1976 Maidstone. The Kent County Council (F.P. 358 (Part) Mersham) 29th July 1982. (513) Public Path Diversion Order 1976 Notice is hereby given that on 7th July the Secretary of State for the Environment confirmed the above-named NORFOLK COUNTY COUNCIL Orders. The effect of the Orders, as confirmed, is to divert that HIGHWAYS Act 1980 part of P.P. 294 Brabqurne for 500 feet generally north- The Norfolk County Council (A149 Antingham Diversion) eastwards from its junction with Quarrington Lane to a new (Classified Road) (Side Roads) Order 1982 length of footpath of not less than 6 feet in width from the point on F.P. 274 500 feet generally north-eastwards Notice is hereby given that the Norfolk County Council of its junction with Quarrington Lane for 220 feet north- have made, and submitted to the Secretary of State for westwards, then 200 feet south-westwards to join Quarring- the Environment and Transport for confirmation, an Order ton Lane. -

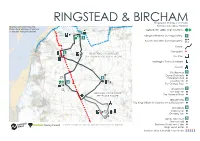

Ringstead and Bircham

RINGSTEAD & BIRCHAMRingstead 17 miles / 27.25 km Business open times may vary. Bircham 6.5 miles / 10.5 km Please check withvenue if you look Defibrillator (AED) map location. to use their facilities & services. Village reference (cycling routes). 1 1 Business location (cycling routes). Route. Start point. 2 RINGSTEAD CYCLE ROUTE SEE ‘RURAL RAGS, RURAL RICHES’ Bus Stop Heritage / Point Of Interest Church THORNHAM 1 Drove Orchards 4 Thornham Deli 3 Lifeboat Inn The Orange Tree RINGSTEAD 2 Gin Trap Inn BIRCHAM CYCLE ROUTE The General Store SEE ‘FLOUR POWER’ SEDGEFORD 3 The King William IV Country Inn & Restaurant DOCKING 4 Railway Inn Docking Fish GREAT BIRCHAM 5 Bircham Mill © Crown copyright and database rights 2019 Ordnance Survey 100019340 Bircham Stores and Cafe Kings Head Hotel Peddars Way & Norfolk Coast Path With a pub in each village the Ringstead route passes through, Getting Started it’s the perfect route for leisurely exploration. The shorter This route has two starting points: Bircham route is an ideal route for families; Combined with a Ringstead village green/picnic area (TF705410). visit to the mill, it makes for a great family day out in the Norfolk Bircham Windmill (TF759327). countryside. For those seeking chal-lenge, or faster cyclists that Parking want to visit everything the area has to offer, why not combine For Ringstead starting point there is limited car parking in the the two routes into one loop? village. For Bircham Windmill start point there is on-site car parking West Norfolk has been home to notable politicians, distinguished ladies subject to opening times. -

2010-02 Autumn Issue

0 1 Contents page Editorial 2 Officers' Reports Chairman 3 - 4 Secretary 5 Obituary Alan Pearcey 6 Special Interest Groups Mondays 7 - 11 Tuesdays 12 - 14 Wednesdays 14 - 16 Thursdays 17 - 19 Fridays 19 - 20 Sundays 21 Visits 22 - 24 Talks 24 Miscellaneous 25 – 26 Committee 27 2 Editorial Ann and I only moved to King's Lynn in March last year but we are by no means strangers to the area. You could say our roots are in the Fens; each born and raised no more than an hour's drive from here. In our careers we moved about the country but spent the majority of our working life at Lowestoft before retiring to northern France in 1994. Joining U3A, amongst other societies and groups, was part of a strategy for integrating, but editing the newsletter could have been over-ambitious. In fact we have found support with Penny Dossetor as coordinator, and more recently have been joined by Edward and Judith Harrison. In a way this edition mirrors our experience in discovering U3A. I found that the nature and status of U3A was not well known in the town. The brief statement from the official web-site is (may I say?) rather daunting: U3As are self-help, self-managed lifelong learning co- operatives for older people no longer in full time work, providing opportunities for their members to share learning experiences in a wide range of interest groups and to pursue learning not for qualifications, but for fun. Our experience is that the King's Lynn U3A is an organisation which is varied and welcoming, catering for an eclectic range of interests and activities. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Delegated List

PLANNING COMMITTEE - APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 11.05.2017 04.07.2017 17/00918/RM Mr & Mrs Blackmur Bawsey Application Conifers Lynn Road Bawsey King's Permitted Lynn Reserved Matters Application: construction of a dwelling 24.04.2017 12.07.2017 17/00802/F Miss Joanna Francis Burnham Norton Application Sea Peeps 19 Norton Street Permitted Burnham Norton Norfolk To erect two timber gates and ancillary picket panel fencing across the driveway entrance 12.04.2017 17.07.2017 17/00734/F Mr J Graham Burnham Overy Application The Images Wells Road Burnham Permitted Overy Town King's Lynn Construction of bedroom 22.02.2017 30.06.2017 17/00349/F Mr And Mrs J Smith Brancaster Application Carpenters Cottage Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe Norfolk Use of Holiday accommodation building as an unrestricted C3 dwellinghouse, including two storey and single storey extensions to rear and erection of detached outbuilding 05.04.2017 07.07.2017 17/00698/F Mr & Mrs G Anson Brancaster Application Brent Marsh Main Road Permitted Brancaster Staithe King's Lynn Demolition of existing house and -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

Final Race Information 3 July 2021 Holkham Hall, Norfolk

FINAL RACE INFORMATION 3 JULY 2021 HOLKHAM HALL, NORFOLK COVID-19 Statement from Wells-next-the-Sea. The main entrance for the public, cars and small Welcome to the second in the series of Outlaw Triathlon Weekends. coaches to Holkham Park, the Hall and other attractions, is via the north Guidance for this event is designed to help mitigate the spread of Covid- gates of the estate on Park Road. 19 as well as deliver an event where all participants, crew, volunteers, suppliers, and any supporters feel safe and have an enjoyable experience. By train: The nearest train station is King’s Lynn (approximately 23 miles away), which has hourly trains running from King’s Cross, London via In line with government guidance, we would recommend that Cambridge and Ely. Train times can be found by telephoning National Rail parents/guardians/carers attending the event complete a lateral flow test Enquiries: (08457) 484950 or visiting www.qjump.co.uk. and only travel to the event should they return a negative result. If you or your child feel unwell in the lead up to the event, please DO NOT attend By bus: The Norfolk Coasthopper runs from King’s Lynn and Hunstanton to and seek medical advice. Sheringham and has two stops at Holkham. The main bus stop is on the main road in Holkham village. In the summer the service is surprisingly We encourage everyone over the age of 12 that comes onto the event site frequent. The Hall is reached via Park Road, approximately a 3/4 mile walk to please wear a face covering. -

North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain

Sheet 24 7000 1900 4500 9100 Adopted King’s Lynn & West Norfolk Local Plan 1998 3400 Marsh Common Inset 33 Drain 0004 5.2m North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain Dismantled Railway Drain Wootton Carr Drain Drain 7887 Drain This Map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk. LA086045. 1999. Maps produced by Lovell Johns Ltd., Oxford. England. SCALE 1:5000 Track Valerian Drain Cattle Grid Drain Playing Field Drain Drain Club Track The Old Gatehouse Drain Pavilion 5572 Greenacres Drain Marsh Common Drain Pond Drain MARSH ROAD GATEHOUSE LANE 0065 3.7m AONB 3 1061 Drain Seacroft 7659 1 York House 2 CLOSE Drain Pond 1 Honeysuckle Cottage FREDERICK 6 BM 11.80m 4157 The Pinfold The Green 2356 The Green 11.3m 5456 11.9m Ponds LING COMMON LANE Glenhaven 1 Drain Dunster School 16 18 Drain Farm 0153 17 Ling Common Drain RECTORYCLOSE Pond AONB Nordean OLD The Old Rectory Dalliance The Old School Red Roofs 12 North Wootton 11.6m Drain Innisfree Tyla BM 12.94m Drain Lingwood House on the Green Winder 4 (PH) Laguegua Berleen 5 Chalet House 245 15 Wootton Carr 14 House On The Drain Rowan House Berleen Green LING COMMON ROAD 19.2m Drain 10 (PH) TCB 6 8 Woodside 14.9m 0047 Rectory Cottage 4 LING COMMON ROAD Pond PO El Sub Sta Orchard Lodge 21 BM 10.61m SANDRINGHAM 26 12 25 13 1 CRESCENT -

KING's LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014

KING'S LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014 Contractor ref: NG/25382/4 NG37 Setchey, Bridge Layby 804 1542 Setchey, Church 805 1541 Setchey, A10 Garage 806 1540 West Winch, A10 opp The Mill 810 1534 West Winch, A10 ESSO Garage 812 1532 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25372/4 NG38 Blackborough End, Bus Shelter 750 1540 Middleton, School Road 752 1538 North Runcton, New Road Post Box 755 1535 West Winch, Coronation Avenue 757 1533 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 800 1530 West Winch, Hall Lane, junction of Eller Drive 802 1528 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Laurel Grove 804 1526 West Winch, Back Lane / Common Close 805 1525 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 820 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25371/4 NG39 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 803 1542 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Eller Avenue 806 1540 West Winch, Long Lane / Hall Lane phone box 808 1538 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: EG/19968/1 EG 1 Gayton Thorpe, Phone Box 805 1610 Gayton, opp The Crown 810 1605 Gayton, Lynn Road / Winch Road 816 1559 Gayton, Lynn Road / Whitehouse Service Station 818 1557 Ashwicken, B1145 / Well Hall Lane 821 1554 Ashwicken, B1145 / Pott Row Turn 823 1552 Ashwicken, B1145 / East Winch Road 825 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 840 1535 Contractor ref: NG/19970/1 NG 3 Wolferton, Friar Marcus Stud 757 1609 Wolferton, Village Sign 758 1610 Sandringham, Gardens 804 1603 West Newton, Bus Shelter 807 1600 Castle Rising, Bus Stop 813 1554 North Wootton, Bus Shelter 817 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 835 1535 @ CONNECTS WITH BUS TO/FROM CONGHAM Contractor ref: Flitcham, Fruit Farm 748 1624 Congham, Manor Farm 758 1614 ..