Sea Defences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

6 June 2016 Applications Determined Under

PLANNING COMMITTEE - 6 JUNE 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 09.03.2016 29.04.2016 16/00472/F Mr & Mrs M Carter Bagthorpe with Barmer Application Cottontail Lodge 11 Bagthorpe Permitted Road Bircham Newton Norfolk Proposed new detached garage 18.02.2016 10.05.2016 16/00304/F Mr Glen Barham Boughton Application Wits End Church Lane Boughton Permitted King's Lynn Raising existing garage roof to accommodate a bedroom with ensuite and study both with dormer windows 23.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00590/F Mr & Mrs G Coyne Boughton Application Hall Farmhouse The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Amendments to extension design along with first floor window openings to rear. 11.03.2016 05.05.2016 16/00503/F Mr Scarlett Burnham Market Application Ulph Lodge 15 Ulph Place Permitted Burnham Market Norfolk Conversion of roofspace to create bedroom and showerroom 16.03.2016 13.05.2016 16/00505/F Holkham Estate Burnham Thorpe Application Agricultural Barn At Whitehall Permitted Farm Walsingham Road Burnham Thorpe Norfolk Proposed conversion of the existing barn to residential use and the modification of an existing structure to provide an outbuilding for parking and storage 04.03.2016 11.05.2016 16/00411/F Mr A Gathercole Clenchwarton Application Holly Lodge 66 Ferry Road Permitted Clenchwarton King's Lynn Proposed replacement sunlounge to existing dwelling. -

North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain

Sheet 24 7000 1900 4500 9100 Adopted King’s Lynn & West Norfolk Local Plan 1998 3400 Marsh Common Inset 33 Drain 0004 5.2m North Wootton/South Wootton Drain Drain Dismantled Railway Drain Wootton Carr Drain Drain 7887 Drain This Map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Borough Council of King’s Lynn and West Norfolk. LA086045. 1999. Maps produced by Lovell Johns Ltd., Oxford. England. SCALE 1:5000 Track Valerian Drain Cattle Grid Drain Playing Field Drain Drain Club Track The Old Gatehouse Drain Pavilion 5572 Greenacres Drain Marsh Common Drain Pond Drain MARSH ROAD GATEHOUSE LANE 0065 3.7m AONB 3 1061 Drain Seacroft 7659 1 York House 2 CLOSE Drain Pond 1 Honeysuckle Cottage FREDERICK 6 BM 11.80m 4157 The Pinfold The Green 2356 The Green 11.3m 5456 11.9m Ponds LING COMMON LANE Glenhaven 1 Drain Dunster School 16 18 Drain Farm 0153 17 Ling Common Drain RECTORYCLOSE Pond AONB Nordean OLD The Old Rectory Dalliance The Old School Red Roofs 12 North Wootton 11.6m Drain Innisfree Tyla BM 12.94m Drain Lingwood House on the Green Winder 4 (PH) Laguegua Berleen 5 Chalet House 245 15 Wootton Carr 14 House On The Drain Rowan House Berleen Green LING COMMON ROAD 19.2m Drain 10 (PH) TCB 6 8 Woodside 14.9m 0047 Rectory Cottage 4 LING COMMON ROAD Pond PO El Sub Sta Orchard Lodge 21 BM 10.61m SANDRINGHAM 26 12 25 13 1 CRESCENT -

KING's LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014

KING'S LYNN SCHOOLS Including King Edward VII High, Springwood High, King's Lynn Academy SCHOOL Timetables from September 2014 Contractor ref: NG/25382/4 NG37 Setchey, Bridge Layby 804 1542 Setchey, Church 805 1541 Setchey, A10 Garage 806 1540 West Winch, A10 opp The Mill 810 1534 West Winch, A10 ESSO Garage 812 1532 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25372/4 NG38 Blackborough End, Bus Shelter 750 1540 Middleton, School Road 752 1538 North Runcton, New Road Post Box 755 1535 West Winch, Coronation Avenue 757 1533 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 800 1530 West Winch, Hall Lane, junction of Eller Drive 802 1528 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Laurel Grove 804 1526 West Winch, Back Lane / Common Close 805 1525 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 820 1510 Contractor ref: NG/25371/4 NG39 West Winch, Gravel Hill Lane / Oak Avenue 803 1542 West Winch, Hall Lane,opp Eller Avenue 806 1540 West Winch, Long Lane / Hall Lane phone box 808 1538 King's Lynn Academy, Bus Loop 835 1510 Contractor ref: EG/19968/1 EG 1 Gayton Thorpe, Phone Box 805 1610 Gayton, opp The Crown 810 1605 Gayton, Lynn Road / Winch Road 816 1559 Gayton, Lynn Road / Whitehouse Service Station 818 1557 Ashwicken, B1145 / Well Hall Lane 821 1554 Ashwicken, B1145 / Pott Row Turn 823 1552 Ashwicken, B1145 / East Winch Road 825 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 840 1535 Contractor ref: NG/19970/1 NG 3 Wolferton, Friar Marcus Stud 757 1609 Wolferton, Village Sign 758 1610 Sandringham, Gardens 804 1603 West Newton, Bus Shelter 807 1600 Castle Rising, Bus Stop 813 1554 North Wootton, Bus Shelter 817 1550 Springwood High School, Bus Loop 835 1535 @ CONNECTS WITH BUS TO/FROM CONGHAM Contractor ref: Flitcham, Fruit Farm 748 1624 Congham, Manor Farm 758 1614 .. -

Settlement Hierarchy the Introduction to the Borough Set out in a Previous

Settlement Hierarchy The introduction to the borough set out in a previous chapter outlines some of the issues arising from its rural nature i.e. the abundance of small villages and the difficulties in ensuring connectivity and accessibility to local services and facilities. The Plan also imposes a requirement to define the approach to development within other towns and in the rural areas to increase their economic and social sustainability. This improvement will be achieved through measures that: a. support urban and rural renaissance; b. secure appropriate amounts of new housing, including affordable housing, local employment and other facilities; and c. improve accessibility, including through public transport. Consequently, it is necessary to consider the potential of the main centres, which provide key services, to accommodate local housing, town centre uses and employment needs in a manner that is both accessible, sustainable and sympathetic to local character. Elsewhere within the rural areas there may be less opportunity to provide new development in this manner. Nevertheless, support may be required to maintain and improve the relationships within and between settlements that add to the quality of life of those who live and work there. Matters for consideration include the: a. viability of agriculture and other economic activities; b. diversification of the economy; c. sustainability of local services; and d. provision of housing for local needs. Policy LP02 Settlement Hierarchy (Strategic Policy) 1. The settlement hierarchy ranks settlements according to their size, range of services/facilities and their possible capacity for growth. As such, it serves as an essential tool in helping to ensure that: a. -

Babingley Catchment Outreach Report-NGP

THE BABINGLEY RIVER CATCHMENT Links between geodiversity and landscape - A resource for educational and outreach work - Tim Holt-Wilson Norfolk Geodiversity Partnership CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Landscape Portrait 3.0 Features to visit 4.0 Local Details 5.0 Resources 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Babingley River is a chalk river, of which there are more in England than any other country in the world. Chalk rivers are fed from groundwater sources, producing clear waters. Most of them have ‘winterbourne’ stretches in their headwaters, with intermittent or absent flow in summer. They have characteristic plant communities, and their gravelly beds, clear waters and rich invertebrate life support important populations of brown trout, salmon and other fish. The Babingley is the best example of a chalk river in west Norfolk. This report explains the links between geodiversity and the biological and cultural character of the river catchment. It provides a digest of information for education and interpretive outreach about this precious natural resource. Some specialist words are marked in blue and appear in the Glossary (section 5). 2.0 LANDSCAPE PORTRAIT 2.1 Topography and geology The Babingley River is a river in north-west Norfolk with a length of 19.6 km (12 miles). The river falls some 25 m (82 ft) from its headwaters at Flitcham to where it meets the sea at Wootton Marshes. This represents a mean fall of approximately 1.27 m (4.2 ft) per km. However this fall is mostly accomplished over a distance of 7.7 km upstream of Babingley Bridge (Castle Rising), at a steeper gradient of 3.24 m per km. -

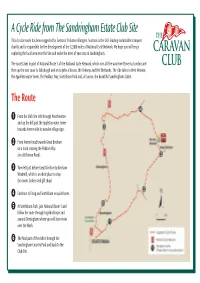

Sandringham CR

A Cycle Ride from The Sandringham Estate Club Site This circular route has been suggested by Sustrans’ Volunteer Rangers. Sustrans is the UK’s leading sustainable transport charity and is responsible for the development of the 12,000 miles of National Cycle Network. We hope you will enjoy exploring the local area near the Site and make the most of your stay at Sandringham. The route takes in part of National Route 1 of the National Cycle Network, which runs all the way from Dover to London and then up the east coast to Edinburgh and on to John o'Groats, the Orkneys and the Shetlands. The ride takes in West Newton, the Appleton water tower, the Peddars Way, Snettisham Park and, of course, the beautiful Sandringham Estate. The Route 1 From the Club Site ride through West Newton and up the hill past the Appleton water tower towards Anmer with its wooden village sign. 2 From Anmer head towards Great Bircham on a track crossing the Peddars Way (an old Roman Road). 3 Turn left just before Great Bircham to Bircham Windmill, which is an ideal place to stop (tea room, bakery and gift shop). 4 Continue to Fring and Snettisham on quiet lanes. 5 At Snettisham Park, join National Route 1 and follow the route through Ingoldisthorpe and around Dersingham where you will have views over the Wash. 6 The final part of the ride is through the Sandringham Country Park and back to the Club Site. The Route Starting point: The Sandringham Estate Caravan Club Site End point: The Sandringham Estate Caravan Club Site Distance: 151/2 miles Grade: Easy Surface: Tarmac with about 2 miles off-road Traffic: Very light Suitability for young children: YES Hills: One long hill shortly after the start. -

Listed Buildings and Scheduled Ancient Monuments in King’S Lynn and West Norfolk

Listed Buildings and Scheduled Ancient Monuments In King’s Lynn and West Norfolk with IDox References 10th Edition March 2020 2 LISTED BUILDINGS Property Designation IDox Ref No ANMER St Mary’s Church II* 763 ASHWICKEN Church Lane All Saints Church II* 1248 War Memorial II 1946 BABINGLEY Ruins of Church of St Felix I & SAM 1430 BAGTHORPE WITH BARMER Bagthorpe St Mary’s Church II 764 1 – 4 Church Row II 765 (Listed as 9 and 10 cottages 25m S of Church) II 766 Hall Farmhouse II 767 K6 Telephone kiosk NW of Church II 770 Barmer Barn 50m N of Barmer Farmhouse II 768 All Saints Church II* 769 BARTON BENDISH Barton Hall II 771 Dog Kennels 20m N Barton Hall II 772 St Mary’s Church I 773 Church Road St Andrew’s Church I 774 Barton Bendish War Memorial II 1948 26 (Listed as Old Post Office) II 775 27 (Listed as cottage adjacent to Old Post Office) II 776 Avenue House II 777 Buttlands Lane K6 Telephone kiosk II 778 BARWICK Great Barwick Barwick Hall II 779 Stable block 10m S Barwick Hall II 780 Little Barwick Barwick House II 781 Stable block 10m NE Barwick House II 782 Carriage block 50m NE Barwick House II 783 BAWSEY Ruined church of St James I & SAM 784 Church Farmhouse II 785 Mintlyn Ruined church of St Michael II* 786 Font against S side Whitehouse Farmhouse II 787 (farmhouse not listed) 3 BEXWELL Barn north of St Mary’s Church II & SAM 1421 Church of St Mary The Virgin II* 1422 Bexwell Hall Farmhouse II 1429 War Memorial A10 Bexwell/Ryston II 1908 BIRCHAM Bircham Newton All Saints Church II* 788 The Old House II 789 Bircham Tofts Ruined Church -

SITE ALLOCATIONS and DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT POLICIES PLAN Adopted September 2016 SADMP

SITE ALLOCATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT POLICIES PLAN Adopted September 2016 SADMP Contents Contents A Introduction 2 B Minor Amendments to Core Strategy 10 C Development Management Policies 16 C.1 DM1 - Presumption in Favour of Sustainable Development 16 C.2 DM2 - Development Boundaries 17 C.3 DM2A - Early Review of Local Plan 20 C.4 DM3 - Development in the Smaller Villages and Hamlets 21 C.5 DM4 - Houses in Multiple Occupation 24 C.6 DM5 - Enlargement or Replacement of Dwellings in the Countryside 26 C.7 DM6 - Housing Needs of Rural Workers 27 C.8 DM7 - Residential Annexes 30 C.9 DM8 - Delivering Affordable Housing on Phased Development 32 C.10 DM9 - Community Facilities 34 C.11 DM10 - Retail Development 36 C.12 DM11 - Touring and Permanent Holiday Sites 38 C.13 DM12 - Strategic Road Network 41 C.14 DM13 - Railway Trackways 44 C.15 DM14 - Development associated with the National Construction College, Bircham Newton and RAF Marham 50 C.16 DM15 - Environment, Design and Amenity 52 C.17 DM16 - Provision of Recreational Open Space for Residential Developments 54 C.18 DM17 - Parking Provision in New Development 57 C.19 DM18 - Coastal Flood Risk Hazard Zone (Hunstanton to Dersingham) 59 C.20 DM19 Green Infrastructure/Habitats Monitoring and Mitigation 64 C.21 DM20 - Renewable Energy 68 C.22 DM21 - Sites in Areas of Flood Risk 70 C.23 DM22 - Protection of Local Open Space 72 D Settlements & Sites - Allocations and Policies 75 SADMP Contents E King's Lynn & Surrounding Area 83 E.1 King's Lynn & West Lynn 83 E.2 West Winch 115 E.3 South -

King's Lynn and West Norfolk Borough Council (Anmer

THE SANDRINGHAM ROYAL ESTATE It will be noticed that no public rights of way have been claimed across land comprising the Sandringham Royal Estate. As this is a private estate of Her Majesty the Queen it was mistakenly omitted from inclusion in the original survey of the definitive map and statement due to the belief that the estate was exempt from the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 as Crown Land. The Sandringham Royal Estate does not in fact qualify as Crown Land as a private estate of Her Majesty the Queen. All public rights of way within the Estate have, therefore, been mistakenly excluded from this survey. DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY KING'S LYNN AND WEST NORFOLK DISTRICT PARISH OF ANMER This parish lies wholly within the Sandringham Royal Estate which is exempt from the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, 1949. PARISH OF BAGTHORPE-WITH-BARMER Restricted Byway No. 1 (Barmer-South Creake Road to Parish Boundary). Starts from the Barmer to South Creake Road, opposite Restricted Byway No. 2, and runs north north-westwards to the parish boundary. Restricted Byway No. 2 (Barmer-South Creake Road to Parish Boundary). Starts from the Barmer-South Creake Road and runs south eastwards for approximately 330 yards, then bears more easterly running through Manor Ling Wood to the parish boundary where it joins Syderstone Restricted Byway No. 4. Restricted Byway No. 3 (Barmer-South Creake Road to Parish Boundary). Starts from the Barmer-South Creake Road at Barmer Farm and runs in a south easterly direction to the parish boundary at the north east corner of Twenty Acre Plantation where it joins Syderstone Restricted Byway No. -

Norfolk Map Books

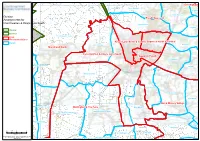

Dersingham North Wootton Congham Castle Rising Division Freebridge Lynn Arrangements for Clenchwarton & King's Lynn South South Wootton Roydon County District Terrington St. Clement Final Recommendations King's Lynn North & Central Gaywood North & Central Parish Clenchwarton Grimston Marshland North Clenchwarton & King's Lynn South Gaywood South Bawsey Walpole Cross Keys Leziate Tilney All Saints North Runcton Walpole Middleton East Winch Nar & Wissey Valleys Terrington St. John Watlington & The Fens West Winch Wiggenhall St. Germans Tilney St. Lawrence Walpole Highway Pentney Wormegay 00.5 1 2 Watlington Tottenhill Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Wiggenhall St. Mary Magdalen 100049926 2016 Marshland St. James Wiggenhall St. Mary Magdalen Shouldham North Creake Heacham Stanhoe Sedgeford Docking South Creake Barwick North Coast Division Arrangements for Snettisham Fring Dersingham Syderstone Bagthorpe with Barmer Docking County Ingoldisthorpe Shernborne Bircham District Dunton Final Dersingham Recommendations Tattersett East Rudham Parish Anmer Houghton Sandringham Dersingham Fakenham & The Raynhams North Wootton Flitcham with Appleton West Rudham Harpley Helhoughton Hillington Marshland North Raynham Castle Rising Little Massingham Terrington St. Clement Freebridge Lynn Congham South Wootton Roydon Weasenham St. Peter Gaywood North & Central Grimston Great Massingham King's Lynn North & Central Weasenham All Saints Clenchwarton Tittleshall Clenchwarton -

Geological Landscapes of the Norfolk Coast

Geological Landscapes of the Norfolk Coast Introducing five areas of striking geodiversity in the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Dersingham National Nature Reserve CONTENTS [clicking on relevant content lines will take you straight to the page] 1.0 Introduction---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 2.0 An overview of the Geodiversity of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 4 3.0 Geological Landscapes------------------------------------------------------------------------ 7 3.1 WEST NORFOLK SANDSTONES ------------------------------------------------------ 7 3.2 HUNSTANTON GLACIAL----------------------------------------------------------------10 3.3 NORTH NORFOLK COASTAL ---------------------------------------------------------13 3.4 CROMER RIDGE ---------------------------------------------------------------------------18 3.5 EAST NORFOLK COASTAL ------------------------------------------------------------22 APPENDIX 1 – Summary of Geological Stratigraphy in the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty-----------------------------------------------------------------25 APPENDIX 2 – Glossary -------------------------------------------------------------------------------27 APPENDIX 3 Geodiversity Characterisation & Conservation------------------------30 A3.1 WEST NORFOLK SANDSTONES Conservation and enhancement --------32 A3.2 HUNSTANTON GLACIAL Conservation and enhancement