The Role of Major Contractors in the Delivery of Public Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parker Review

Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership An update report from The Parker Review Sir John Parker The Parker Review Committee 5 February 2020 Principal Sponsor Members of the Steering Committee Chair: Sir John Parker GBE, FREng Co-Chair: David Tyler Contents Members: Dr Doyin Atewologun Sanjay Bhandari Helen Mahy CBE Foreword by Sir John Parker 2 Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE Foreword by the Secretary of State 6 Trevor Phillips OBE Message from EY 8 Tom Shropshire Vision and Mission Statement 10 Yvonne Thompson CBE Professor Susan Vinnicombe CBE Current Profile of FTSE 350 Boards 14 Matthew Percival FRC/Cranfield Research on Ethnic Diversity Reporting 36 Arun Batra OBE Parker Review Recommendations 58 Bilal Raja Kirstie Wright Company Success Stories 62 Closing Word from Sir Jon Thompson 65 Observers Biographies 66 Sanu de Lima, Itiola Durojaiye, Katie Leinweber Appendix — The Directors’ Resource Toolkit 72 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Thanks to our contributors during the year and to this report Oliver Cover Alex Diggins Neil Golborne Orla Pettigrew Sonam Patel Zaheer Ahmad MBE Rachel Sadka Simon Feeke Key advisors and contributors to this report: Simon Manterfield Dr Manjari Prashar Dr Fatima Tresh Latika Shah ® At the heart of our success lies the performance 2. Recognising the changes and growing talent of our many great companies, many of them listed pool of ethnically diverse candidates in our in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250. There is no doubt home and overseas markets which will influence that one reason we have been able to punch recruitment patterns for years to come above our weight as a medium-sized country is the talent and inventiveness of our business leaders Whilst we have made great strides in bringing and our skilled people. -

Firstgroup Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents

FirstGroup plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents Strategic report Summary of the year and financial highlights 02 Chairman’s statement 04 Group overview 06 Chief Executive’s strategic review 08 The world we live in 10 Business model 12 Strategic objectives 14 Key performance indicators 16 Business review 20 Corporate responsibility 40 Principal risks and uncertainties 44 Operating and financial review 50 Governance Board of Directors 56 Corporate governance report 58 Directors’ remuneration report 76 Other statutory information 101 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 106 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 107 Consolidated balance sheet 108 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 109 Consolidated cash flow statement 110 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 111 Independent auditor’s report 160 Group financial summary 164 Company balance sheet 165 Notes to the Company financial statements 166 Shareholder information 174 Financial calendar 175 Glossary 176 FirstGroup plc is the leading transport operator in the UK and North America. With approximately £6 billion in revenues and around 110,000 employees, we transported around 2.4 billion passengers last year. In this Annual Report for the year to 31 March 2015 we review our performance and plans in line with our strategic objectives, focusing on the progress we have made with our multi-year transformation programme, which will deliver sustainable improvements in shareholder value. FirstGroup Annual Report and Accounts 2015 01 Summary of the year and -

Annual Report 2016 Contents at a Glance

IG GROUP HOLDINGS PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CONTENTS AT A GLANCE COMPANY OVERVIEW ’2016 was another At a Glance 2 record year for IG, CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 4 with revenue up 14% STRATEGIC REPORT Chief Executive Officer’s Review 6 to £456.3 million. Our Business 10 Our investments in Our Product Suite 12 Our Clients and Business Model 14 improving online Our People 16 marketing, developing Our Strategic Objectives 20 new offices and Our Operational Strategy in Action 22 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) 28 extending our product Business Conduct and Sustainability 30 set are beginning to Operating and Financial Review 36 Managing Our Risks 44 pay off.’ CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT Chairman’s Introduction to Corporate Governance 56 Peter Hetherington Corporate Governance Statement 57 Chief Executive Officer The Board 58 19 July 2016 Nomination Committee 68 Directors’ Remuneration Report 70 Audit Committee 90 Board Risk Committee 95 Directors’ Report 98 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 101 Independent Auditors’ Report 102 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Group Income Statement 108 Statements of Financial Position 109 Cash Flow Statements 112 Notes to the Financial Statements 113 INVESTOR RESOURCES Five-Year Summary 166 Examples 168 Glossary 174 Global Offices 177 Shareholder and Company Information 178 This report is fully accessible online at: iggroup.com/ar2016 FOUR-YEAR COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATES 5.6% 2.9% REVENUE(1) PROFIT BEFORE TAX 4.4% 8.7% 8.9% DILUTED TOTAL OWN FUNDS EARNINGS DIVIDEND GENERATED FROM PER SHARE PER SHARE OPERATIONS REVENUE(1) PROFIT BEFORE TAX OWN FUNDS GENERATED FROM OPERATIONS £456.3m £207.9m £197.9m £193.2m £400.2m £159.2m £366.8m £361.9m £370.4m £388.4m £185.7m £192.2m £194.9m £169.5m £140.7m £154.3m £160.6m £136.8m FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 DILUTED EARNINGS TOTAL DIVIDEND PER SHARE PER SHARE 44.58p 31.40p 41.07p 28.15p (1) Throughout this report Revenue refers to net trading revenue (ie excluding interest on segregated client funds and after taking account of introducing partner commissions). -

Annual Report & Accounts 2017

Annual Report & Accounts 2017 Direct Line Insurance Group plc Annual Report & Accounts 2017 A year of strong progress Contents Paul Geddes, CEO of Direct Line Group, commented: “2017 is the fifth successive year in which we have Strategic report delivered a strong financial performance. We have 1 Group highlights seen significant growth in our direct own brand policies 2 Our investment case as more customers respond positively to the many 4 Group at a glance improvements we have made to the business. This 6 Business model success has resulted in our proposing an increase in the final dividend by 40.2% to 13.6 pence, bringing the 8 Chairman’s statement total ordinary dividend to 20.4 pence and declaring a 10 Chief Executive Officer’s review special dividend of 15.0 pence. This amounts to a cash 12 Market overview return of £486 million to shareholders. 14 Our strategy 20 Our key performance indicators “At half year we refreshed our medium-term targets 22 Risk management and our results show we’ve been delivering on our 26 Corporate social responsibility management priorities to maintain revenue growth, 30 Operating review reduce expense and commission ratios and deliver 34 Finance review underwriting and pricing excellence. Governance “Looking to the future, this success enables us to continue investing in our technology and customer experience, 44 Chairman’s introduction supporting our plans to grow the business whilst 46 Board of Directors improving efficiency. Together with our track record of 48 Executive Committee delivery, these give -

DATABANK INSIDE the CITY SABAH MEDDINGS the WEEK in the MARKETS the ECONOMY Consumer Prices Index Current Rate Prev

10 The Sunday Times February 10, 2019 BUSINESS Liam Kelly LETTERS 56-year-old chairman of before Serco and others got Send your letters, including executive had the audacity to arrangements a business has. Mrs M&S awaits her love sausage housebuilder Taylor Wimpey into a pickle for overcharging SIGNALS full name and address, describe me as a “dangerous For those already using a has been keen to link his the government to tag AND NOISE . to: The Sunday Times, threat” to the company. supported package, there is Much derision for Marks & Prufrock wonders name to several recruitment criminals, ushering in a 1 London Bridge Street, Calantzopoulos has likely to be no additional cost. Spencer after the high street whether Rowe, 51, plans to processes, including the dark period for outsourcers. London SE1 9GF. Or email: spearheaded PMI’s drive for For those using spreadsheets, stalwart unveiled a heart- treat the Mrs M&S in his life — chairmanships of John Lewis Beeston knows how tricky [email protected] safer products. That doesn’t bridging products are shaped “love sausage” as a his wife, Jo, an ardent Marks Partnership and the suit hire recruitment can be: he’s on Letters may be edited make him a hypocrite, but a available at about £20 a year. treat for a romantic breakfast shopper — to a love sausage chain Moss Bros. the nominations committee realist. André is an engineer: Our MTD service is live to on Valentine’s Day. on Thursday. He has been at Taylor of the Premier League, careful, methodical, logical. -

Act Annual Conference

EVENT OVERVIEW ACT ANNUAL CONFERENCE 21-22 May 2019 Manchester Central, UK ATTENDEE PROFILE TOTAL 9/10 DELEGATES ATTENDEES WOULD RECOMMEND 1075 THE EVENT TO A FRIEND/COLLEAGUE FROM OR ATTEND AGAIN 388COMPANIES 88 DELEGATES SPONSORS AND REPRESENTING 323 EXHIBITORS COMPANIES 97SPEAKERS 548 INCLUDING: • Anglo American • London Stock Exchange • Arup • Mitsubishi • ASOS • National Express • AstraZeneca • National Oilwell Varco SENIORITY OF • BAE Systems • Pearson • Balfour Beatty • Petrofac Services CORPORATE AUDIENCE • BASF • Primark • BT • PZ Cussons • Burberry • RELX • Centrica • Renewi • Compass Group • Rentokil • Deliveroo • Royal Dutch Shell • Drax • Sainsbury’s • Dyson • Schneider Electric • easyJet • Scottish Power • Electrocomponents • Serco • Equiniti • Sky • Etihad Airways • Stagecoach • Farfetch • Statoil • Google UK • Tate & Lyle • GSK • Tesco • Halfords • Thames Water • Hammerson • Thomas Cook • Heathrow Airport • Travelport • Hitachi Capital • UK Power Networks • InterContinental Hotels • Urenco • ITV • Virgin Media • JD Sports Fashion • Vodafone • John Lewis • WorldPay BOARD LEVEL/STRATEGIC LEADER 52% • Just Eat • Yildirim Holdings MANAGERIAL 30% OF COMPANIES CORPORATE SENIOR OPERATIONAL 17% THAT ATTENDED DELEGATES WITH JOB AS DELEGATES TITLES INCLUDING: TACTICAL 1% WERE GROUP TREASURER, HEAD 50% CORPORATE. 107 OF TREASURY, HEAD OF CORPORATE FINANCE EVENT OVERVIEW CONTENT AND FEEDBACK TOTAL NETWORKING TOTAL CONTENT AVAILABLE 10.3 29.4 HOURS HOURS LIBOR DIGITAL TREASURY TOP TOPICS SUSTAINABLE FINANCE PAYMENT INNOVATION AND RISKS OPEN BANKING GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC FINANCING MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT EVENT APP SOCIAL MEDIA UNIQUE USERS: 435 726 TWEETS TOTAL APP GENERATED USING PAGE VIEWS: 74,666 #ACTAC19 DELEGATE FEEDBACK “THE ACT ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROVIDES AN EXCELLENT “IF YOU ONLY ATTEND ONE EVENT IN A YEAR, MAKE IT THE OPPORTUNITY TO NETWORK WITH OTHER TREASURY ACT ANNUAL CONFERENCE. -

FTSE Russell Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.43 UNITED Bytes Technology Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Investment Trust 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 4imprint Group 0.18 UNITED C&C Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Worldwide Inv Tst 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.25 UNITED Cairn Energy 0.17 UNITED Electrocomponents 1.18 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.33 UNITED Caledonia Investments 0.25 UNITED Elementis 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.51 UNITED Capita 0.15 UNITED Energean 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Airtel Africa 0.19 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.29 UNITED Essentra 0.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AJ Bell 0.31 UNITED Carnival 0.54 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.26 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.77 UNITED Centamin 0.27 UNITED European Opportunities Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Allianz Technology Trust 0.31 UNITED Centrica 0.74 UNITED F&C Investment Trust 1.1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AO World 0.18 UNITED Chemring Group 0.2 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Apax Global Alpha 0.17 UNITED Chrysalis Investments 0.33 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.4 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.19 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore -

Case No COMP/M.3554 - SERCO / NEDRAILWAYS / NORTHERN RAIL

EN Case No COMP/M.3554 - SERCO / NEDRAILWAYS / NORTHERN RAIL Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 16/09/2004 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 32004M3554 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 16.09.2004 In the published version of this decision, some information has been omitted pursuant to Article SG-Greffe(2004) D/204043/204044 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information PUBLIC VERSION omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION To the notifying party Subject: Case No COMP/M.3554 - Serco/NedRailways/Northern Rail JV Notification of 13.8.2004 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 139/20041 Dear Sir/Madam, 1. On 13.08.2004, Serco Group plc (“Serco”) and NedRailways BV (“NedRailways”) notified their intention to acquire joint control of the Northern passenger rail franchise (“Northern franchise”) within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the EC Merger Regulation (“EC Merger Regulation”). 2. After examining the notification, the Commission has concluded that the notified operation falls within the scope of the Merger Regulation and that it does not raise any serious doubts as to its compatibility with the common market and with the EEA agreement. I. THE PARTIES 3. Serco is active in transport services including rail and metro in the UK, where it runs the Docklands Light Railway and the Metrolink in Manchester. -

Under the Bonnet Alex Savvides, JOHCM UK Dynamic Fund

March 2018 FOR PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS ONLY Under the Bonnet Alex Savvides, JOHCM UK Dynamic Fund Investment background year Treasury yields have risen by 46bps since the start of the year to the end of February, in the UK the 10-year After the explosive start to 2018 by global stock gilt yield is up by 31bps. The UK unemployment rate markets, particularly in the US, February was a poor for the three months to December was 4.4% whilst in and volatile month. The ongoing strength in economic the US it was 4.1%. Wage inflation in the UK, judged conditions, hardening evidence of inflationary pressures by average weekly earnings, rose by 2.6% in December and intensifying threats of faster interest rate increases and by 2.5% for the final three months, compared to finally spilled over to cause a short but intense sell-off 2.9% wage growth in the US. UK inflation, driven higher in equities. by a weak pound sterling, remained at 2.7% (CPIH) Although difficult to pinpoint the specific trigger for in January (or 3% excluding housing costs), whilst in the market fall, it was most likely a reaction to US the US it is at 1.7%. Expectations in the US this year wage inflation pressures emanating from the ongoing are for three interest rate rises, although noise around strength in the US labour market, made worse by the four increases is growing, particularly given hawkish recent rapid rises in the US equity indices. January non- comments in late February from Jerome Powell, the new farm payrolls, released on the 2nd February, grew by a Chair of the Federal Reserve. -

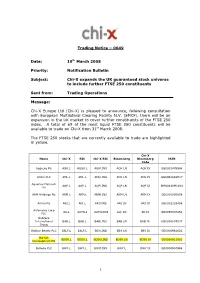

20080319 Trading Notice Functional 0049

Trading Notice – 0049 Date: 19 th March 2008 Priority: Notification Bulletin Subject: Chi-X expands the UK guaranteed stock universe to include further FTSE 250 constituents Sent from: Trading Operations Message: Chi-X Europe Ltd (Chi-X) is pleased to announce, following consultation with European Multilateral Clearing Facility N.V. (EMCF), there will be an expansion in the UK market to cover further constituents of the FTSE 250 index. A total of 69 of the most liquid FTSE 250 constituents will be available to trade on Chi-X from 31 st March 2008. The FTSE 250 stocks that are currently available to trade are highlighted in yellow. Chi-X Name Chi-X RIC Chi-X RIC Bloomberg Bloomberg ISIN Code Aggreko Plc AGK.L AGGK.L AGKl.INS AGK LN AGK IX GB0001478998 Amlin PLC AML.L AML.L AMLl.INS AML LN AML IX GB00B2988H17 Aquarius Platinum AQP.L AQP.L AQPl.INS AQP LN AQP IX BMG0440M1284 Ltd ARM Holdings Plc ARM.L ARM.L ARMl.INS ARM LN ARM IX GB0000595859 Arriva Plc ARI.L ARI.L ARIl.INS ARI LN ARI IX GB0002303468 Autonomy Corp AU.L AUTN.L AUTNl.INS AU/ LN AU IX GB0055007982 PLC Babcock International BAB.L BAB.L BABl.INS BAB LN BAB IX GB0009697037 Group Balfour Beatty PLC BALF.L BALF.L BBYl.INS BBY LN BBY IX GB0000961622 Barratt BDEV.L BDEV.L BDEVl.INS BDEV LN BDEV IX GB0000811801 Development Plc Bellway PLC BWY.L BWY.L BWYl.INS BWY.L BWY IX GB0000904986 1 Biffa PLC BIFF.L BIFF.L BIFFl.INS BIFF LN BIFF IX GB00B129PL77 Bradford & Bingley BB.L BB.L BBl.INS BB/ LN BB IX GB0002228152 PLC Bunzl PLC BNZL.L BNZL.L BNZLl.INS BNZL LN BNZL IX GB00B0744B38 Burberry -

CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2019 C0. Introduction

Centrica response: CDP Climate Change 2019 Centrica response: CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2019 C0. Introduction C0.1 (C0.1) Give a general description and introduction to your organization. About us - Centrica is an international energy and services company focused on satisfying the changing needs of our customers. We supply energy and services to over 25m customer accounts mainly in the UK, Ireland and North America, through strong brands such as British Gas, Direct Energy and Bord Gáis Energy, supported by around 15,000 engineers and technicians. Our areas of focus for growth are Energy Supply, Services, Connected Home, Distributed Energy & Power and Energy Marketing & Trading. Following our strategic review in 2015 and the transformation of our business to focus on our customers, we have divested or decommissioned the majority of our power generation assets, placed our Exploration & Production assets into a joint venture and ceased gas storage at our Rough storage facility. As a result, we will continue to focus our CDP response and be scored under the Electric Utilities module. Our impact on climate change - Our direct carbon emissions under scope 1 include those from sources we own or control such as power generation, gas production and storage as well as emissions arising from our property, fleet and travel. Indirect carbon emissions under scope 2 arise from electricity purchased and consumed across our offices and assets. Scope 3 emissions are those we do not produce but are the result of products and services we provide, such as electricity and gas sold to customers from wholesale markets alongside products and services purchased to run our business. -

Delivering Responsible Infrastructure Solutions

John Laing Group plc John Laing Group DELIVERING Annual Report & Accounts RESPONSIBLE INFRASTRUCTURE SOLUTIONS 2019 John Laing Group plc Annual Report & Accounts 2019 WE ARE JOHN LAING DELIVERING INFRASTRUCTURE SOLUTIONS JOHN LAING IS DELIVERING INFRASTRUCTURE SOLUTIONS. WE ARE INVESTORS AND PARTNERS BEHIND RESPONSIBLE INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS WHICH RESPOND TO PUBLIC NEEDS, EMPOWER SUSTAINABLE GROWTH AND IMPROVE THE LIVES OF THE COMMUNITIES IN WHICH WE WORK. CLARENCE CORRECTIONAL CENTRE, THE INTERCITY EXPRESS PROGRAMME, ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE AND MIDDLE EAST p / 18 p / 24 I-75 ROAD, RUTA DEL CACAO, NORTH AMERICA LATIN AMERICA p / 32 p / 42 Our Alignment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals While our projects have overlaps across many of the UN SDGs, we have identified 5 priority SDGs which our investments most directly contribute to. For further information on this, please see page 64. 2019 HIGHLIGHTS CONTENTS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS OVERVIEW 1 > NAV per share at 337p at 31 December 2019 2019 Highlights 2 At a Glance (31 December 2018 – 323p) 4 Our Global Reach Overview > 4.3% increase since 31 December 2018; 7.2% increase before 6 Chairman’s Statement dividends paid; STRATEGIC REPORT > 10.7% increase at constant currency and before dividends paid1 8 Chief Executive Officer’s Review > Final dividend 7.66p per share (including a special dividend 14 Our Strategy and Business Model of 3.98p per share), giving a total dividend for 2019 of 9.50p 16 Key Performance Indicators 20 Regional Review > Investment commitments of £184 million