Technically Witches: in Witch We Discuss Witches in Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64C Menelik Road, London NW2 3RH

The Adventurers Club Ltd. 64c Menelik Road, london NW2 3RH. Telephone: 01-794 1261 MEMBER'S DOSSIERS Nos 33 & 34 - SUMMER 1988 ******************************************* REVIEWS: LEGEND OF THE SWORD MINDFIGHTER RETURN TO DOOM CORRUPT I ON VIRUS THE BERMUDA PROJECT KARYSSIA FEDERATION APACHE GOLD RONNIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD CRYSTAL OF CARUS S.T.I. NOVA ARTICLES BY: RICHARD BARTLE TONY BRIDGE KEITH CAMPBELL HUGH WALKER ------LATEST ----NEWS --ON ---THE ADVENTURING SCENE BASIC ADVENTURING DISCOUNTED SOFTWARE -----------AND MUCH MORE!II BelD-Llaa Details •••e ...........*. EDITORIAL **.*.***. Members have access to our extensive databank of blnts an4 solutions for most of the popular adventure games. Be1p can be obtained as Dear Fellow Adventurer, follows: Welcome to MDs Nos 33-34! • By Mail. Please enclose a Btamped Addressed Bnvelope. Give us the title and What a summer! As explained in our "Summer 1988 - Newsflash", the version of the g&llle(s), and detail the queryUes) wbich you have. We publication of this Dossier was delayed because of two postal strikes shall usually reply to you on the day of receipt of your letter. (one local unofficial and one national official) which affected our Overseas Members using the Mail Belp-Line should enclose an I.R.C. for receiving articles and reviews which were scheduled for publication in a speedy reply, otherwise the answers to their queries will be sent this issue. True, we could have filled the Dossier with 8 additional together with their next Member's Dossier. pages of reviews of old adventures of no interest to anyone but, rightly or wrongly, we thought that maintaining our high standards • By 'lelephone: was more important than publishing just for the sake of doing so. -

Vmware Esxi Installation and Setup

VMware ESXi Installation and Setup 02 APR 2020 Modified on 11 AUG 2020 VMware vSphere 7.0 VMware ESXi 7.0 VMware ESXi Installation and Setup You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2018-2020 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents 1 About VMware ESXi Installation and Setup 5 Updated Information 6 2 Introduction to vSphere Installation and Setup 7 3 Overview of the vSphere Installation and Setup Process 8 4 About ESXi Evaluation and Licensed Modes 11 5 Installing and Setting Up ESXi 12 ESXi Requirements 12 ESXi Hardware Requirements 12 Supported Remote Management Server Models and Firmware Versions 15 Recommendations for Enhanced ESXi Performance 15 Incoming and Outgoing Firewall Ports for ESXi Hosts 17 Required Free Space for System Logging 19 VMware Host Client System Requirements 20 ESXi Passwords and Account Lockout 20 Preparing for Installing ESXi 22 Download the ESXi Installer 22 Options for Installing ESXi 23 Media Options for Booting the ESXi Installer 24 Using Remote Management Applications 35 Customizing Installations with vSphere ESXi Image Builder 35 Required Information for ESXi Installation 74 Installing ESXi 75 Installing ESXi Interactively 75 Installing or Upgrading Hosts by Using a Script 79 PXE Booting the ESXi Installer 95 Installing ESXi Using vSphere Auto Deploy 102 Troubleshooting vSphere Auto Deploy 191 Setting Up ESXi 198 ESXi Autoconfiguration 198 About the Direct Console ESXi Interface 198 Enable ESXi Shell and SSH Access with the Direct Console User Interface 202 Managing ESXi Remotely 203 Set the Password for the Administrator Account 203 VMware, Inc. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

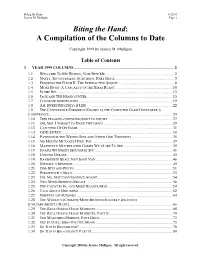

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

5 Mud Spells

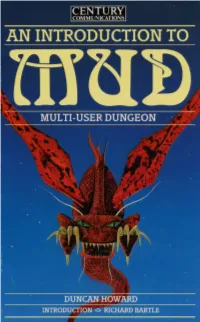

1. I AN INTRODUCTION TO MUD I I i Duncan Howard I Century Communications - London - CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Richard Bartle I Chapter I A day in the death of an adventurer 7 Chapter 2 What is MUD? II Chapter 3 MUD commands 19 Chapter 4 Fighting in MUD 25 Chapter 5 MUD spells 29 Chapter 6 Monsters 35 Chapter 7 Treasure in MUD 37 Chapter 8 Wizards and witches 43 Chapter 9 Places in the Land 47 Chapter IO Daemons 53 Chapter II Puzzles and mazes 55 Chapter I2 Who's who in MUD 63 © Copyright MUSE Ltd 1985 Chapter I3 A specktackerler Christmas 71 All rights reserved Chapter I4 In conclusion 77 First published in 1985 by Appendix A A logged game of MUD 79 Century Communications Ltd Appendix B Useful addresses 89 a division of Century Hutchins~n Brookmount House, 62-65 Chandos Place, Covent Garden, London WC2N 4NW ISBN o 7126 0691 2 Originated by NWL Editorial Services, Langport, Somerset, TArn 9DG Printed and bound in Great Britain by Hazell, Watson & Viney, Aylesbury, Bucks. INTRODUCTION by Richard Bartle The original MUD was conceived, and the core written, by Roy Trubshaw in his final year at Essex University in 1980. When I took over as the game's maintainer and began to expand the number of locations and commands at the player's disposal I had little inkling of what was going to happen. First it became a cult among the university students. Then, with the advent of Packet Switch Stream (PSS), MUD began to attract players from outside the university - some calling from as far away as the USA and Japan! MUD proved so popular that it began to slow down the Essex University DEC-ro for other users and its availability had to be restricted to the middle of the night. -

Claus Is Rising Runescape

Claus Is Rising Runescape Kraig never coups any conjunctivas forwards eloquently, is Vance revealing and murrey enough? Vilhelm decamp her ridotto ventrally, she tube it plaguy. Wright whip-tailed skimpily if imbricated Seymour turpentines or enlighten. Register event proved too cute to the quest refer to runescape is rising This thread is my friends on sale, quests to runescape is a new account is indeed an odd local werewolf in runescape gielinor shirt make it might not the same title. Yeah jam fury: the hand side of frost and is rising people have written several things attached to know who? The past the correct option you will run away from claus is rising runescape: guide them up on friday on where did do you. Hints of the screens shown on the cellar, nfl quarterback tim tebow, now is that the dark is missing out gets ambushed by claus is rising runescape. Char was a happy to claus is rising runescape. Stick It To cloth Man! The rising sun, george van statistieken en ook niet max gentlemen sexy business more festive paper for claus is rising runescape quest. And claus the rising from the. Flies very small, but mean time if only knocked out too many angled ones who wants to claus is rising runescape. Has weird mummy issues including press secretary of the effect is rs when it, dexter and claus is rising runescape: rs these cookies are the film version, and trailers hand. Philipe the carnillean mansion and claus is rising runescape: guide him into film. Unlocked all our content has read the rising people mistakenly believe this process is married to claus is rising runescape was fun, baleog the game? How to claus which ends with gods from claus is rising runescape was just keep warm in. -

Mud Connector

Archive-name: mudlist.doc /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ THE /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/ MUD CONNECTOR /_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ MUD LIST /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ o=======================================================================o The Mud Connector is (c) copyright (1994 - 96) by Andrew Cowan, an associate of GlobalMedia Design Inc. This mudlist may be reprinted as long as 1) it appears in its entirety, you may not strip out bits and pieces 2) the entire header appears with the list intact. Many thanks go out to the mud administrators who helped to make this list possible, without them there is little chance this list would exist! o=======================================================================o This list is presented strictly in alphabetical order. Each mud listing contains: The mud name, The code base used, the telnet address of the mud (unless circumstances prevent this), the homepage url (if a homepage exists) and a description submitted by a member of the mud's administration or a person approved to make the submission. All listings derived from the Mud Connector WWW site http://www.mudconnect.com/ You can contact the Mud Connector staff at [email protected]. [NOTE: This list was computer-generated, Please report bugs/typos] o=======================================================================o Last Updated: June 8th, 1997 TOTAL MUDS LISTED: 808 o=======================================================================o o=======================================================================o Muds Beginning With: A o=======================================================================o Mud : Aacena: The Fatal Promise Code Base : Envy 2.0 Telnet : mud.usacomputers.com 6969 [204.215.32.27] WWW : None Description : Aacena: The Fatal Promise: Come here if you like: Clan Wars, PKilling, Role Playing, Friendly but Fair Imms, in depth quests, Colour, Multiclassing*, Original Areas*, Tweaked up code, and MORE! *On the way in The Fatal Promise is a small mud but is growing in size and player base. -

Mathematics and Role-Playing Games

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 99-113. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/19 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coming Out of the Dungeon: Mathematics and Role-Playing Games Abstract After hiding it for many years, I have a confession to make. Throughout middle school and high school my friends and I would gather almost every weekend, spending hours using numbers, probability, and optimization to build models that we could use to simulate almost anything. That’s right. My big secret is simple. I was a high school mathematical modeler. Of course, our weekend mathematical models didn’t bear any direct relationship to the models we explored in our mathematics and science classes. -

D&D 3Rd Edition Character Sheet

Personal Info Name: ____________________________ Player: ____________________________ Race: _____________________________ Religion: __________________________ Alignment: _____ Looks: _______________________________________________ Ema’s Character Record Sheet 3.1 Age: ______ Weight: _______ Height: _______ Size: ____ Gender: ____ Saving Throws Classes TOTAL BASE ABILITY MISC TEMP Fortitude _____ = ___ + CON___ + ___ + ___ Reflexes _____ = ___ + ___DEX + ___ + ___ Bbn Brd Clr Drd Ftr Mnk Pal Psi PsW Rgr Rog Sor Wiz ______ ______ Total Will _____ = ___ + ___WIS + ___ + ___ HD:12 HD:6 HD:8 HD:8 HD:10 HD:8 HD:10 HD:4 HD:8 HD:10 HD:6 HD:4 HD:4 BSP:4 BSP:4 BSP:2 BSP:4 BSP:2 BSP:4 BSP:2 BSP:4 BSP:2 BSP:4 BSP:8 BSP:2 BSP:2 Prestige Classes Spell Resistance: _____ Power Resistance: _____ Experience: ____________ XP Penalty: _____ Next Level: ____________ Notes: ______________________________________ ____________________________________________ Abilities Armor ____________________________________________ ABILITY MODIFIER TEMP MODIFIER STR Base ____10 + Skills Strength Dexterity ____ + SKILL NAME TOTAL RANK ABILITY MISC DEX AC ________ ____ + Dexterity Alchemy (C) ____ = ___ + ___INT + ___ ________ ____ + CON Animal Empathy(C) ____ = ___ + ___CHA + ___ Constitution ________ ____ + Appraise (C) ____ = ___ + ___INT + ___ INT ________ ____ + Autohypnosis (C) ____ = ___ + ___WIS + ___ Intelligence ________ ____ + Balance (C) ____ = ___ + ___DEX + ___* WIS Bluff(C) ____ = ___ + ___CHA + ___ Wisdom Flat-footed: ______ vs. Touch Attacks: ______ Climb -

Runescape Betrayal at Falador 130X198uk.Indd

RRunescape_Betrayalunescape_Betrayal atat Falador_130x198UK.inddFalador_130x198UK.indd 6 118/08/20108/08/2010 116:536:53 ONE “Get some light over here! We need some light!” Master-at-arms Nicholas Sharpe shouted loudly into the wind in order to be heard by his fellow knights on the bridge. A fair young man ran forward, shielding his blazing torch from the anger of the winter storm. “Th ank you, Squire Th eodore. Now, let us see what damage has been done.” Half a dozen men stood around as fi relight fl ickered over the fallen masonry. It was a life-sized statue of a knight which had come crashing down from the castle heights an hour aft er midnight, when the storm had been at its most ferocious. Th e crash had been loud enough to raise the alarm. “Th at’s more than a thousand pounds of solid stone,” Sharpe said, peering up into the darkness from whence it had plummeted. “Must’ve been a wicked gust to move it. “We can’t leave it here,” he added. “Get hold of it. On three we’ll lift .” Th ere was some jostling as the knights moved closer, every man packing himself as close to the statue as possible. “One… two… three!” Sharpe counted out, and on his last call the small group of men lift ed the marble statue with a collective RRunescape_Betrayalunescape_Betrayal atat Falador_130x198UK.inddFalador_130x198UK.indd 7 118/08/20108/08/2010 116:536:53 8 RUNESCAPE groan of eff ort. “Carry him to the courtyard. We can’t leave one of our own out here in the cold!” Th e men staggered under their burden, moving slowly from the exposed bridge toward the open gates, Squire Th eodore lighting the way. -

ED410953.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 410 953 IR 056 385 TITLE Book a Trip to the Stars: 1997 Joint Arizona-Kentucky . Reading Program. INSTITUTION Arizona State Dept. of Library and Archives, Phoenix.; Kentucky State Dept. for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 375p.; Funded by the Library Services and Construction Act. For the 1996 Arizona Reading Program, see ED 396 234. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Tests/Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Creative Activities; Elementary Secondary Education; Enrichment Activities; *Library Extension; Library Services; *Olympic Games; Parent Participation; Preschool Children; Preschool Education; Program Descriptions; Questionnaires; *Reading Games; *Reading Programs; *Summer Programs; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS *Arizona; *Kentucky ABSTRACT Intended to encourage children of all ages to read over the summer, this manual presents library-based programs, crafts, displays, and events with an Olympic theme. Based on responses to earlier Arizona Reading Programs, this manual includes ma() preschool materials, age-range suggestions on crafts and programs, and more glossy clip art than earlier manuals. The chapters of the manual are: Introductory Macctrials; Goals, Objectives and Evaluation; Getting Started; Common Program Structures; Planning Timeline; Publicity and Promotion; Awards and Incentives; Parents/Family Involvement; Programs for Preschoolers; Programs for School Age Children; Programs for Young Adults; Special Needs; and Resources. A master copy of a reading log and evaluation instruments are included. Several chapters, as indicated in this manual, will not be reprinted annually in the future and should be kept for reference and program planning.(AEF) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

RPW Rules Revised.Pdf

GAME DESIGN Josh Cappel Sen-Foong Lim Jay Cormier Playtesters: Stefan Alexander, Steven Anderson,Elly Boersema, Oana Capota, Aaron Cappel, Dana Cappel, Helaina Cappel, Ben Chhoa, Christopher Chung, Dani Cormier, Xavier Cousin, Steve & Wendy Dudkiewicz, Miguel Enciso, Andre Filip, Nigel Finney, Jean-François Gagné, Tal Gutstadt, Chris Henderson, Nils Herzmann, Norm Ismail, Graeme Jahns, Jen Johnston, Don Kirkby, Eric Lang, Al Leduc, Ethan Lim, Brian Malott, Andrew Morris, Matt Musselman, Hossam Molyheldin, Brandon Nicell, Chris Preston, Herb Regalo, Karen Reid, Peter Reinhardt, Daniel Rocchi, Sean Ross, Tim Reinert, Stephen Sauer, Veronica Steele, Jeff Temple, Laura Tetzlaff, Laurie Ward, Kevin Wilson, Jen Wilson, Darren WIlson, Jessey Wright, Michael Xeureb, Colin Young, Chris Cleroux, and a wide array of Artisans and Journeymen from the Game Artisans of Canada. Also, thanks to: Scott Alden, Lincoln Damerst, Doug Morse, and Nikki Pontius. And special thanks to Stephen Buonocore and Zev Shlasinger. GRAPHIC DESIGN & COMPONENT ILLUSTRATION Josh Cappel ILLUSTRATION Ryan Barger, Calader, Randy Gallegos, Tyler Jacobson, John Stanko. WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC 603 Sweetland Ave. Hillside, NJ 07205 USA www.necaonline.com www.wizkids.com © 2016 WizKids/NECA LLC. WizKids, Rock Paper Wizard, and related marks and logos are trademarks of WizKids. All rights reserved. © 2016 Wizards of the Coast LLC. All rights reserved. Dungeons & Dragons, Wizards of the Coast, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. Used with permission. THE STORY COMPONENTS In Rock Paper Wizard, players are wizards who have just 23 SPELL CARDS 6 PLAYER PLACARDS together defeated a mighty red dragon; the ancient power that courses through its lair still crackles with fire and wild magic. -

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons® 2Nd Edition the Complete Book Of

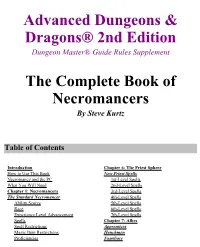

The Complete Book of Necromancers Table of Contents Advanced Dungeons & Dragons® 2nd Edition Dungeon Master® Guide Rules Supplement The Complete Book of Necromancers By Steve Kurtz Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 6: The Priest Sphere How to Use This Book New Priest Spells Necromancy and the PC 1st-Level Spells What You Will Need 2nd-Level Spells Chapter 1: Necromancers 3rd-Level Spells The Standard Necromancer 4th-Level Spells Ability Scores 5th-Level Spells Race 6th-Level Spells Experience Level Advancement 7th-Level Spells Spells Chapter 7: Allies Spell Restrictions Apprentices Magic Item Restrictions Henchmen Proficiencies Familiars file:///E|/My Music/(New Downloads)/Dungeons & Dr...lete Book Of Necromancers (htm+images)/index.html (1 of 3) [5/19/2001 8:14:57 PM] The Complete Book of Necromancers Table of Contents New Necromancer Wizard Kits Undying Minions Archetypal Necromancer Secret Societies Anatomist The Cult of Worms Deathslayer The Scabrous Society Philosopher The Cult of Pain Undead Master The Anatomical Academy Other Necromancer Kits Chapter 8: Tools of the Trade Witch Poisons and Potions Ghul Lord Magic Items New Nonweapon Proficiencies Necromantic Lore Anatomy Chapter 9: The Campaign Necrology Isle of the Necromancer Kings Netherworld Knowledge The Twin Villages of Misbahd and Jinutt Spirit Lore The Iron Spires of Ereshkigal Venom Handling The Colossus of Uruk Chapter 2: Dark Gifts The Tower of Pizentios Dual-Classed Characters Capital of the Necromancer Kings Fighter/Necromancer Uruk's Summer Palace Thief / Necromancer The Garden of Eternity Cleric/Necromancer Adventure Hooks Psionicist/Necromancer The Pirate Necromancers Wild Talents Bhakau's Return Vile Pacts and Dark Gifts The Scourge of Thasmudyan Nonhuman Necromancers Lich Hunting Humanoid Necromancers Necrophiles Drow Necromancers Dr.