Studia Orientalia 114

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

146 Farmacologos Andalusies

Farmacólogos andalusíes: punta de lanza de la farmacia medieval Moreno Toral, Esteban ; Ramos Carrillo, Antonio; Rojas Álvarez, Mª Ángeles Facultad de Farmacia. Universidad de Sevilla. La ciencia árabe, medieval en general, estará caracterizada por dos notas particulares: la primera, el gran poder de asimilación de los conocimientos, tanto de las civilizaciones anteriores a ellos como de los pueblos con los que entra en contacto durante la expansión del Islam; y la segunda, el carácter enciclopédico de la gran mayoría de las obras de sabios y científicos árabes. Podemos afirmar por tanto que la ciencia árabe de los siglos VIII y IX se encuentra en período de formación, en la que coexisten aspectos científicos, empíricos y mágicos. Todo este caldo de cultivo del saber, no eclosionaría en Al-Andalus hasta bien entrado el siglo X, casi un siglo más tarde que en Oriente, alcanzando gran madurez y producción en la Córdoba califal. Durante el califato de Abderrahman III, Córdoba se constituye como un gran centro del mundo científico y cultural. Ello se debe a tres causas: las peregrinaciones a la Meca, los viajes de estudio, cada vez más frecuentes en quienes pretendían ocupar algún puesto destacado en el mundo cultural de la Corte, y la importación de sabios orientales a Córdoba con el fin de emular a Bagdad. Todo ello supondría el auge y desarrollo de disciplinas como la Astronomía, las Matemáticas, la Ingeniería, la Medicina, la Botánica y la Farmacología. Con este excepcional substrato, no resulta extraño que se dieran las circunstancias idóneas para la aparición de una pléyade de grandes figuras, cuyo legado a la humanidad, en todas las ramas del saber, ha sido de gran valor. -

Medical Breakthroughs in Islamic Medicine Zakaria Virk, Canada

Medical Breakthroughs in Islamic Medicine Zakaria Virk, Canada ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Physicians occupied a high social position in the Arab and Persian culture. Prominent physicians served as ministers or judges of the government and were also appointed as royal physicians. Physicians were well-versed in logic, philosophy and natural sciences. All of the prominent Muslim philosophers earned their livelihood through the practice of medicine. Muslim physicians made astounding break throughs in the fields of allergy, anatomy, bacteriology, botany, dentistry, embryology, environmentalism, etiology, immunology, microbiology, obstetrics, ophthalmology, pathology, pediatrics, psychiatry, psychology, surgery, urology, zoology, and the pharmaceutical sciences. The Islamic medical scholars gathered vast amounts of information, from around the known world, added their own observations and developed techniques and procedures that would form the basis of modern medicine. In the history of medicine, Islamic medicine stands out as the period of greatest advance, certainly before the technology of the 20th century. Aristotle teaching, from document in the British Library, showing the great reverence of the Islamic scholars for their Greek predecessor 1 This article will cover remarkable medical feats -

JISHIM 2017-2018-2019.Indb

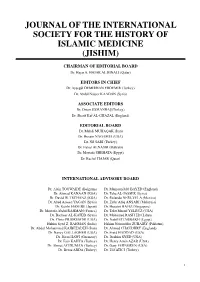

JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) CHAIRMAN OF EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Hajar A. HAJAR AL BINALI (Qatar) EDITORS IN CHIEF Dr.'U$\üHJLLO'(0,5+$1(5'(0,5 7XUNH\ Ayşegül DEMIRHAN ERDEMIR (Turkey) 'U$EGXO1DVVHU.$$'$1 6\ULD ASSOCIATE EDITORS 'U2]WDQ860$1%$û 7XUNH\ 'U6KDULI.DI$/*+$=$/ (QJODQG EDITORIAL BOARD 'U0DKGL08+$4$. ,UDQ 'U+XVDLQ1$*$0,$ 86$ 'U1LO6$5, 7XUNH\ 'U)DLVDO$/1$6,5 %DKUDLQ 'U0RVWDID6+(+$7$ (J\SW 'U5DFKHO+$-$5 4DWDU INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Alan TOUWAIDE (Belgum) Dr. Mamoun MO BAYED (England) Dr. Ahmad KANAAN (KSA) Dr. Taha AL-JASSER (Syra) Dr. Davd W. TSCHANZ (KSA) Dr. Rolando NERI-VELA (Mexco) Dr. Abed Ameen YAGAN (Syra) Dr. Zafar Afaq ANSARI (Malaysa) Dr. Kesh HASEBE (Japan) Dr. Husan HAFIZ (Sngapore) Dr. Mustafa Abdul RAHMAN (France) Dr. Talat Masud YELBUZ (USA) Dr. Bacheer AL-KATEB (Syra) Dr. Mohamed RASH ED (Lbya) Dr. Plno PRIORESCHI (USA) Dr. Nabl El TABBAKH (Egypt) Hakm Syed Z. RAHMAN (Inda) Hakm Namuddn ZUBAIRY (Pakstan) Dr. Abdul Mohammed KAJBFZADEH (Iran) Dr. Ahmad CHAUDHRY (England) Dr. Nancy GALLAGHER (USA) Dr. Frad HADDAD (USA) Dr. Rem HAWI (Germany) Dr. Ibrahm SYED (USA) Dr. Esn KAHYA (Turkey) Dr. Henry Amn AZAR (USA) Dr. Ahmet ACIDUMAN (Turkey) Dr. Gary FERNGREN (USA) Dr. Berna ARDA (Turkey) Dr. Elf ATICI (Turkey) I JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) Perods: Journal of ISHIM s publshed twce a year n Aprl and October. Address Changes: The publsher must be nformed at least 15 days before the publcaton date. All artcles, fgures, photos and tables n ths journal can not be reproduced, stored or transmtted n any form or by any means wthout the pror wrtten permsson of the publsher. -

Arabic Manuscripts the CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY

A HANDLIST OF THE Arabic Manuscripts THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY A HANDLIST OF THE Arabic Manuscripts Volume VI. MSS. 4501-5000 BY ARTHUR J. ARBERRY LITT,D., F.B.A. Sir Thomas Adams's Professor of Arabic in the University of Cambridge With 22 plates DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS & CO., LTD. 1963 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, OXFORD BY VIVIAN RIDLER PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTIONS OF MANUSCRIPTS 45or (r) RISALA FI 'L-$AN'AT AL-ILAHIYA, by al-Shaikh MAGHUSH. [A tract on alchemy; foll. r-6.] Any other copy? Foll. 7-74 contain extracts from various works on alchemy includ ing books by Ibn Umail, al-Jildaki and Jabir al-~adiq .. Foll. 7 5-77 contain some poems. (2) RISA.LA FI 'L-$AN'AT AL-ILAHITA [Anon.]. [ A fragment of a text on alchemy; foll. 78-97.] Any other copy? (3) RISA.LA QAIDARUS. [A similar tract; foll. 98-ro2.] Any other copy? Foll. ro3-4 contain further alchemical extracts. Foll. I 04. r 9· 5 x r 5·7 cm. Clear scholar's naskh. Undated, r 2/ I 8th century. 4502 MAURID AL-?AM:AN FI RASM AL-QUR'.J.N, by Abu eAbd Allah Muhammad. b. Muhammad. b. Ibrahim al-U1nawi al- Sharishi AL-KHARRAZi (ft. 703/1303). [ A metrical treatise on the orthography of the Qur~an.] Foll. 22. 21·3 x I 5·8 cm. Clear scholar's maghribi. Undated, r r/r7th century. Brockeln1ann ii. 248, Suppl. ii. 349• 45°3 SHLI.RH AL-RISALAT AL-PdT]JlrA, by Ma)}mud b# lv!u. -

Christian Apostate Literature in Medieval Islam Dissertation

Voices of the Converted: Christian Apostate Literature in Medieval Islam Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Clint Hackenburg, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Kevin van Bladel, Advisor Bilal Orfali Hadi Jorati Copyright by Clint Hackenburg 2015 Abstract This dissertation seeks to discuss the dialectical (kalām) and scriptural (both biblical and qurʾānic) reasoning used to justify Christian conversion to Islam during the medieval period (750 - 1492 C.E.). With this objective in mind, I will compare and contrast the manners in which five different Arabophone authors, ʿAlī ibn Sahl Rabban al-Ṭabarī (d. ca. 860), al-Ḥasan ibn Ayyūb (fl. ca. mid-tenth century), Naṣr ibn Yaḥyā (d. 1163 or 1193), Yūsuf al-Lubnānī (d. ca mid-thirteenth century), and Anselm Turmeda (d. 1423), all Christian converts to Islam, utilized biblical and qurʾānic proof-texts alongside dialectical reasoning to invalidate the various tenets of Christianity while concurrently endorsing Islamic doctrine. These authors discuss a wide variety of contentious issues pervading medieval Christian-Muslim dialogue. Within the doctrinal sphere, these authors primarily discuss the Trinity and Incarnation, the nature of God, and the corruption of the Bible (taḥrīf). Within the exegetical realm, these authors primarily discussed miracles, prophecy, and prophetology. Moreover, this dissertation seeks to discern how these authors and their works can be properly contextualized within the larger framework of medieval Arabic polemical literature. That is to say, aside from parallels and correspondences with one another, what connections, if any, do these authors have with other contemporary Arabophone Muslim, Christian, and, to a lesser extent, Jewish apologists and polemicists? ii In the course of my research on Christian apostate literature, I have come to two primary conclusions. -

History of Islamic Science

History of Islamic Science George Sarton‟s Tribute to Muslim Scientists in the “Introduction to the History of Science,” ”It will suffice here to evoke a few glorious names without contemporary equivalents in the West: Jabir ibn Haiyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Fargani, Al-Razi, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Battani, Hunain ibn Ishaq, al-Farabi, Ibrahim ibn Sinan, al-Masudi, al-Tabari, Abul Wafa, ‘Ali ibn Abbas, Abul Qasim, Ibn al-Jazzar, al-Biruni, Ibn Sina, Ibn Yunus, al-Kashi, Ibn al-Haitham, ‘Ali Ibn ‘Isa al- Ghazali, al-zarqab,Omar Khayyam. A magnificent array of names which it would not be difficult to extend. If anyone tells you that the Middle Ages were scientifically sterile, just quote these men to him, all of whom flourished within a short period, 750 to 1100 A.D.” Preface On 8 June, A.D. 632, the Prophet Mohammed (Peace and Prayers be upon Him) died, having accomplished the marvelous task of uniting the tribes of Arabia into a homogeneous and powerful nation. In the interval, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, the whole North Africa, Gibraltar and Spain had been submitted to the Islamic State, and a new civilization had been established. The Arabs quickly assimilated the culture and knowledge of the peoples they ruled, while the latter in turn - Persians, Syrians, Copts, Berbers, and others - adopted the Arabic language. The nationality of the Muslim thus became submerged, and the term Arab acquired a linguistic sense rather than a strictly ethnological one. As soon as Islamic state had been established, the Arabs began to encourage learning of all kinds. -

I Abd Al Rahman Al-Khazin, 55 Àbd Al-Baqí, 50

Index Abu-l-wafa, 12, 29-30, 33, 43 Abu-lqasim, 31 A Ahmad Al-nahawandi, 11 Ahmed Abuali, 54 Abd Al Rahman Al-khazin, 55 Ahmed Al-nahawandi, 13 Àbd Al-baqí, 50 Ahmed Al-tabari, 31, 35, 54 Abd Al-rahman Al-sufi, 30, 32 Ahmed Ibn Yusuf, 18-19, 21 Abd Al-rahman Ii, 25 Al Baghdadi, 55 Abdellateef Muwaffaq, 55 Al Balkhi, 53 Abu 'umar Ibn Hajjaj, 50 Al Battani Abu Abdillah, 53 Abu Abbas Ibn Tanbugha, 56 Al Farisi Kamalud-deen Abul-hassan, 56 Abu Al-qasim Al-zahravi, 54 Al Majrett'ti Abu-alqasim, 54 Abu Ali Al-khaiyat, 12 Al-'abbas, 11 Abu Baker, 54 Al-'abbas Ibn Sa'id, 12 Abu Bakr, 19, 24 Al-abbas, 11 Abu Hamed Al-ustrulabi, 54 Al-ash'ari, 29 Abu Ja'far 'abdallah Al-mansur, 3 Al-asmai, 53 Abu Ja'far Al-khazin, 30, 32 Al-badee Al-ustralabi, 55 Abu Kamil, 25-27 Al-bakri, 50 Abu Ma'shar, 12 Al-bakrí, 50 Abu Mansour Muwaffak, 30 Al-baladi, 31, 36 Abu Mansur Muwaffak, 36 Al-balkhi, 27 Abu Masour Muwaffak, 31 Al-battani, 19-20, 24, 54 Abu Nasr, 34 Al-biruni, 24, 38-40, 42 Abu Othman, 25-26 Al-bitruji, 55 Abu Raihan Al-biruni, 54 Al-dawla, 30 Abu Sa'id Al Darir, 12 Al-dinawari, 12, 20, 53 Abu Sa'id Al-darir, 11-12 Al-fadl, 4 Abu Sa'id Ubaid Allah, 41, 48 Al-farabi, 54 Abu Sahl Al-masihi, 31, 35 Al-fargham, 12 Abu-hanifa Ahmed Ibn Dawood, 53 Al-farghani, 9, 54 Abu-hasan Ali, 26 Al-fazari, 53 Abu-l-fath, 30, 32 Al-fida, 56 Abu-l-jud, 39, 44 Al-ghazzali, 49-50 Abu-l-qasim, 30, 37 Al-hajjaj Ibn Yusuf, 11 i Index Al-hajjaj Ihn Yusuf, 12 Al-saghani, 33 Al-hasan Ibn Al-sabbah, 50 Al-shaghani, 30 Al-hasib Alkarji, 54 Al-shirazi, 52 Al-hassan Al-murarakishi, 56 Al-sijzi, 30, 32 Al-husain Ibn Ali, 55 Al-sufi, 54 Al-husain Ibn Ibrahim, 31, 35 Al-tabari, 11 Al-idrisi, 55 Al-tamimi, 31, 36 Al-imrani, 25, 27 Al-tamimi Muhammad Ibn Amyal, 54 Al-jahiz, 19-20 Al-tifashi, 55 Al-jildaki, 56 Al-tuhra-ee, 55 Al-juzajani, 47 Al-zarqaili, 49 Al-karkhi, 38-39, 44 Al-zarqal, 50 Al-karmani, 40-41, 45 Al-zarqali, 50, 54 Al-kathi, 40, 45 Al. -

A. Pengertian Sejarah Peradaban Islam 1

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Pengertian Sejarah Peradaban Islam 1. Pengertian Sejarah Secara etimologi, kata sejarah dalam bahasa Indonesia berasal dari bahasa Melayu yang dapat mengambil alih dari bahasa Arab yaitu kata syajarah. Kata tersebut masuk ke dalam perbendaharaan bahasa Indonesia semenjak abad XIII, dimana kata itu masuk ke dalam bahasa Melayu setelah akulturasi kebudayaan Indonesia dengan kebudayaan Islam. Adapun macam-macam kemungkinan arti kata syajarah, adalah: pohon, keturunan, asal-usul, dan juga diidentikkan dengan silsilah, riwayat, babad, tambo, dan tarikh.1 Akulturasi kedua antara kebudayaan Indonesia dengan kebudayaan Barat terjadi sejak abad ke-XV. Akibatnya, kata sejarah mendapatkan tambahan perbendaharaan kata-kata: geschiedenis, historie (Belanda), history (Inggris), histore (Perancis), dan geschicte (Jerman). Kata history yang lebih populer untuk menyebut sejarah dalam ilmu pengetahuan sebenarnya berasal dari bahasa Yunani (istoria) yang berarti pengetahuan tentang gejala-gejala alam, khususnya manusia 1Silsilah berasal dari bahasa Arab yang berarti urutan, seri, hubungan, daftar keturunan. Babad berasal dari bahasa Jawa yang berarti riwayat kerajaan, riwayat bangsa, buku tahunan, kronik. Buku tahunan adalah annual, riwayat peristiwa dalam tiap tahun. Kronik adalah kisah (fakta) peristiwa-peristiwa yang disusun menurut urutan waktu, tanpa menjelaskan hubungan antara peristiwa- peristiwa tersebut. Tarikh juga berasal dari bahasa Arab yang berarti buku tahunan, kronik, perhitungan tahun, buku riwayat, tanggal, pencatatan -

Jewish Medical Practitioners I N the Medieval Muslim World

IN JEWISH MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS PRACTITIONERS JEWISH MEDICAL Explores the lives of Jewish physicians and pharmacists THE in medieval Muslim lands MEDIEVAL MUSLIM WORLD MUSLIM MEDIEVAL This book collects and analyses the available biographical data on Jewish medical practitioners in the Muslim world from the 9th to the 16th century. The biographies are based mainly on information gathered from the wealth of primary sources found in the Cairo Geniza (letters, commercial documents, court orders, lists of donors) and Muslim Arabic sources (biographical dictionaries, historical and geographical literature). The practitioners come from various socio-economic strata and lived in urban as well as rural locations in Muslim countries. Over 600 biographies are presented, enabling readers to explore issues such as professional, daily and personal lives; successes and failures; families; Jewish JEWISH MEDICAL communities; and inter-religious affairs. Both the biographies and the accompanying discussion shed light on various views and aspects of the medicine practised in this P RACTITIONERS IN THE period by Muslim, Jews and Christians. MEDIEVAL MUSLIM Key Features • Offers a unique insight into the life of Jewish physicians and pharmacists, their WORLD families and communities in medieval Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran, North Africa, Sicily and Andalusia A C OLLECTIVE BIOGRAPHY • Shows how Jewish practitioners participated in community leadership, in hospitals and in the courts of the Muslim rulers • Analyses the biographical data to provide information on the relationships among Jews, Muslims and Christians, and between the common people and the elite EFRAIM LEV Efraim Lev is a Professor in the Department of Israel Studies and current Dean of the Faculty of Humanities in the University of Haifa, Israel. -

Kennedy Islamic Mathematical Geography

Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science Volume 1 Edited by ROSHDI RASHED in collaboration with RÉGIS MORELON London and New York First published in 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Structure and editorial matter © 1996 Routledge The chapters © 1996 Routledge Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request. ISBN 0-203-40360-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71184-X (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-12410-7 (Print Edition) 3 volume set ISBN 0-415-02063-8 Contents VOLUME 1 Contents iv Preface vii 1 General survey of Arabic astronomy 1 Régis Morelon 2 Eastern Arabic astronomy between the eighth and the eleventh 21 centuries Régis Morelon 3 Arabic planetary theories after the eleventh century AD 59 George Saliba 4 Astronomy -

Etk/Evk Namelist

NAMELIST Note that in the online version a search for any variant form of a name (headword and/or alternate forms) must produce all etk.txt records containing any of the forms listed. A. F. H. V., O.P. Aali filius Achemet Aaron .alt; Aaros .alt; Arez .alt; Aram .alt; Aros philosophus Aaron cum Maria Abamarvan Abbo of Fleury .alt; Abbo Floriacensis .alt; Abbo de Fleury Abbot of Saint Mark Abdala ben Zeleman .alt; Abdullah ben Zeleman Abdalla .alt; Abdullah Abdalla ibn Ali Masuphi .alt; Abdullah ibn Ali Masuphi Abel Abgadinus Abicrasar Abiosus, John Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Johannes Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Joh. Ablaudius Babilonicus Ableta filius Zael Abraam .alt; Abraham Abraam Iudeus .alt; Abraam Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraam Judeus .alt; Abraham Iudaeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Judaeus Abracham .alt; Abraham Abraham .alt; Abraam .alt; Abracham Abraham Additor Abraham Bendeur .alt; Abraham Ibendeut .alt; Abraham Isbendeuth Abraham de Seculo .alt; Abraham, dit de Seculo Abraham Hebraeus Abraham ibn Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenezra .alt; ibn-Ezra, Avraham .alt; Aben Eyzar ? .alt; Abraham ben Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenare Abraham Iudaeus Tortuosensis Abraham of Toledo Abu Jafar Ahmed ben Yusuf ibn Kummed Abuali .alt; Albualy Abubacer .alt; Ibn-Tufail, Muhammad Ibn-Abd-al-Malik .alt; Albubather .alt; Albubather Alkasan .alt; Abu Bakr Abubather Abulhazen Acbrhannus Accanamosali .alt; Ammar al-Mausili Accursius Parmensis .alt; Accursius de Parma Accursius Pistoriensis .alt; Accursius of Pistoia .alt; M. Accursium Pistoriensem -

Illustrations from the Wellcome Institute Library

Medical History, 1987, 31: 354-357. ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE WELLCOME INSTITUTE LIBRARY THE SAMI HADDAD COLLECTION OF ARABIC MEDICAL MANUSCRIPTS by LAWRENCE I. CONRAD* In September 1985, the London auction firm Sotheby's published a catalogue of Fine Orientalmanuscripts andminiatures to be sold in their rooms on 21-22 November. This sale was of particular interest to historians of medieval Near Eastern medicine, since Lots 457-525 comprised a corpus of ninety-five manuscripts from the collection of the late Sami Haddad. Examination of the manuscripts revealed that this sale represented a unique opportunity for an especially significant acquisition. Furthermore, in view ofthe fact that Arabic medical collections ofthis size and calibre rarely become available, it seemed a matter of particular importance that this corpus should remain intact and available for scholarly research. The proposed sale was therefore brought to the attention of the Wellcome Trustees, who authorized acquisition of the collection and generously provided the necessary funding. Negotiations through Sotheby's came to a successful conclusion on 15 November, with the Wellcome Institute's purchase of the Haddad manuscripts by private treaty. This new addition to the Wellcome Institute's already considerable Arabic holdings comes from the private collection of Dr Sami Ibrahim Haddad, one of the most intriguing and most important medical figures of the modern Middle East. Born in 1890 in Jaffa in Ottoman Palestine, Haddad received his secondary education in Jerusalem, where he excelled as a student, and in 1909 proceeded to advanced medical studies in Beirut at the Syrian Protestant College, which had established a teaching hospital only four years earlier.