Where Is the Transit Oriented Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village of Ossining LWRP Described Below Be Incorporated As Routine Program Changes (Rpcs), Pursuant to Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) Regulations at 15 C.F.R

Village of Ossining Local Waterfront Revitalization Program Adopted: Village of Ossining Board of Trustees, July 2, 1991 Approved: NYS Secretary of State Gail S. Shaffer, July 11, 1991 Concurred: U.S. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resources Management, June 8, 1993 Adopted Amendment: Village of Ossining Board of Trustees, March 16, 2011 Approved: NYS Secretary of State César A. Perales, October 25, 2011 Concurred: U.S. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resources Management, February 1, 2012 This Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP) has been prepared and approved in accordance with provisions of the Waterfront Revitalization of Coastal Areas and Inland Waterways Act (Executive Law, Article 42) and its implementing Regulations (19 NYCRR 601). Federal concurrence on the incorporation of this Local Waterfront Revitalization Program into the New York State Coastal Management Program as a routine program change has been obtained in accordance with provisions of the U.S. Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (p.L. 92-583), as amended, and its implementing regulations (15 CFR 923). The preparation of this program was financially aided by a federal grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. [Federal Grant No. NA-82-AA-D-CZ068.] The New York State Coastal Management Program and the preparation of Local Waterfront Revitalization Programs are administered by the New York State Department of State, Office of Coastal, Local Government and Community Sustainability, One Commerce Plaza, 99 Washington Avenue, Suite 1010, Albany, New York 12231-0001. -

Winter Contingency Schedule for the Haverstraw-Ossining Ferry

H-OFerryContingency_10.18_bw.qxd:Template 11/27/18 2:11 PM Page 1 SUBSTITUTE BUS SCHEDULE WEEKDAY MORNINGS TO GRAND CENTRAL ABOUT THIS SPECIAL WINTER BUS SCHEDULE: AM Light Face, PM Bold Face AM Peak Haverstraw This schedule will be used when icing conditions on the river make the ferry inoperable. Ferry Terminal 5 45 — 6 04 — 6 20 — 6 32 6 50 — 7 15 — 7 45 — 8 20 8 45 Customers will be notified in advance when this schedule will be used. The ferry’s crew will make Tarrytown 1 6 15 — 6 39 — 7 00 — 7 12 7 35 — 8 00 — 8 30 — 9 05 9 30 announcements and distribute notices. Express Express Express Express Express Express Express Information on ferry service will also be available at www.mta.info , from our Customer Information Center at 511, and on local television and radio stations. Tarrytown Rail Station 6 29 6 35 6 48 6 59 7 10 7 16 7 22 7 47 7 41 8 10 8 24 8 36 8 56 9 17 9 44 Metro-North and New York Waterway will activate normal ferry service as soon as river conditions Yonkers — 6 54 7 05 — — 7 37 — — 8 02 — 8 41 — 9 15 9 27 10 00 allow. MTA Metro-North Railroad is committed to providing non-discriminatory service to ensure that no person is excluded from Marble Hill — 7 05 7 12 — — 7 48 — — 8 13 — 8 49 — 9 26 — 10 07 participation in, or denied the benefits of, or subjected to discrimination in the receipt of its services on the basis of race, color, national origin or income as protected by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. -

Mass Transit Task Force Final Report

New NY Bridge Mass Transit Task Force Final Transit Recommendations February 2014 New York State New York State Thruway Authority Department of Transportation New NY Bridge Mass Transit Task Force Final Transit Recommendations Acknowledgements The members of the Mass Transit Task Force (MTTF) rose to the challenge of meeting larger regional needs, while recognizing that all individual ideas may not be integrated into the final proposal. This collective effort resulted in a set of consensus recommendations supported by all MTTF members. The Co-Chairs of the MTTF, New York State Department of Transportation Commissioner Joan McDonald and New York State Thruway Authority Executive Director Thomas Madison are deeply grateful for the time and effort contributed by each MTTF member, their staff and delegates, and the broader community. The collective contributions of all helped shape the future of transit in the Lower Hudson Valley. February 2014 New NY Bridge Mass Transit Task Force Final Transit Recommendations This page intentionally left blank. February 2014 New NY Bridge Mass Transit Task Force Final Transit Recommendations Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 The Mass Transit Task Force 3 3 The Mass Transit Task Force Final Recommendations Summary: A Bus Rapid Transit Network for the New NY Bridge – Simple | Fast | Reliable 7 3.1 What will the BRT system look like? 8 3.2 What does the BRT system offer? 10 3.3 Recommended Short-Term Improvements 11 3.4 Recommended Mid-Term Improvements 12 3.5 Recommended Long-Term Improvements 12 4 History -

Meeting of the Metro-North Railroad Committee March 2016

Meeting of the Metro-North Railroad Committee March 2016 Members J. Sedore, Chair F. Ferrer, MTA Vice Chairman J. Ballan R. Bickford N. Brown J. Kay S. Metzger C. Moerdler J. Molloy M. Pally C. Wortendyke N. Zuckerman Metro-North Railroad Committee Meeting 2 Broadway, 20th Floor Board Room New York, New York Monday, 3/21/2016 8:30 - 9:30 AM ET 1. Public Comments 2. Approval of Minutes Minutes - Page 4 3. 2016 Work Plan 2016 Work Plan - Page 10 4. President's Reports Safety Safety Report - Page 17 MTA Police Report MTA Police Report - Page 19 5. Information Items Information Items - Page 24 Annual Strategic Investments & Planning Studies Annual Strategic Investments & Planning Studies - Page 25 Annual Elevator & Escalator Report Annual Elevator & Escalator Report - Page 51 Track Program Quarterly Update Track Program Quarterly Update - Page 61 6. Procurements Procurements - Page 67 Non-Competitive Non-Competitive - Page 71 Competitive Competitive - Page 73 7. Operations Report Operations Report - Page 83 8. Financial Report Financial Report - Page 92 9. Ridership Report Ridership Report - Page 113 10. Capital Program Report Capital Program Report - Page 123 Joint Meeting with Long Island on Monday, April 18, 2016 at 8:30 am Minutes of the Regular Meeting Metro-North Committee Monday, February 22, 2016 Meeting held at 2 Broadway – 20th Floor New York, New York 10004 8:30 a.m. The following members were present: Hon. Fernando Ferrer, Vice Chairman, MTA Hon. James L. Sedore, Jr., Chairman of the Metro-North Committee Hon. Mitchell H. Pally, Chairman of the Long Island Rail Road Committee Hon. -

Transportation

OSSINING COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Chapter 6: Transportation Goal Improve traffic conditions and roadway safety throughout the Village, increase pedestrian and bicycle opportunities, and support cost effective transit improvements. 6.1 Commutation Patterns As discussed in Chapter 5, Ossining is predominantly a bedroom community for residents who commute to New York City and other employment centers in the region. Demographic data helps to further depict general commutation patterns and trends in the Village. Census data detailed in Table 1 show that the overall number of workers who commute to the Village as of 2017 decreased by 16% since 2002, whereas the number of residents who commute outside of the Village for work has increased. 1 As of 2017, 91% of residents commute to locations outside of the Village for work. Table 1: Village of Ossining Commutation Patterns, 2002 ‐ 2017 2002 2010 2017 Workforce Employed in the Village Count Share Count Share Count Share Employed in the Village 6,531 100% 5,738 100% 5,384 100% Employed in the Village but Living Outside 5,311 81% 4,873 85% 4,463 83% Employed and Living in the Village 1,220 19% 865 15% 921 17% Workforce Living In the Village (Residents) Living in the Village 10,138 100% 9,659 100% 10,370 100% Living in the Village but Employed Outside 8,918 88% 8,794 91% 9,449 91% Living and Employed in the Village 1,220 12% 865 9% 921 9% Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies: 2002‐2017 LEHD Origin Destination Employment Statistics (LODES). While the number of residents who work in the Village has overall decreased since the early 2000s, there have been gains since 2010 (Table 1). -

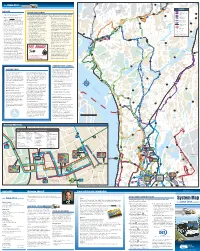

WCDOT Sysmapbrch

C C ro to n F a lls R d R D L O C V R E - L 2 L 2 S T y e To Poughkeepsie d d To Carmel Bowl l al R 77 R V Park-and-Ride L e TLC e n PART2 o k c o i 6N PART2 v a a n l e W L U l P d l a o S R n n o i t r a d w Mahopac e w S d h l 6 a c Village t a d c r s B R A Center d k O Har o R dsc bbl e ra T S o L L r E V O L r E e B l l t t PART2 i u S o M r c LEGEND p a S p PUTNAM o h d a Baldwin HOW TO RIDE M R Regular Service w 0 llo Somers COUNTY o Jefferson 77 Place FOR YOUR SAFETY & COMFORT H Commons Lincolndale ill 16 Express/Limited-Stop ks k Valley 0 1. Arrive at the bus stop at least 5 minutes Pee 6 Service 202 PART2 Bee-Line buses belong to everyone, so please help us to take good care of them! Shrub Oak 16 Memorial Park St early to avoid missing your bus. E Main Rd 118 L Part-time Service us d 12 0 c N o iti 9 t T v R C D S e To ensure the safety and comfort of all Please be courteous to those riding with you: R l N O G l E R 77 O D i Thomas Je#erson Elementary School L l O 16 u 77 k l Shrub Oak r 2. -

Healthy Communities; Traffic Calming & Safety Policy Statements And

Land Use Law Center Gaining Ground Information Database Topic: Healthy Communities; Traffic Calming & Safety Resource Type: Policy Statements and Planning Documents State: New York Jurisdiction Type: Municipal Municipality: Ossining Year (adopted, written, etc.): 2009 Community Type – applicable to: Urban; Suburban Title: Traffic Signals and Narrower Lanes to Improve Safety Document Last Updated in Database: March 18, 2019 Abstract Ossining, New York’s Comprehensive Plan includes traffic-calming measures to be implemented throughout the village, though particularly on Route 9. Route 9 is the primary north-south arterial reaching through Ossining and onto major highways in New York. Route 9’s increasingly congested condition has resulted in residential road use throughout the village. These residential roads are narrow, steep, and winding, and often dangerous during inclement weather. Ossining’s goal is to improve pedestrian safety and comfort, and to change the behavior of motorists who would otherwise use residential roads to bypass congestion on the major roads. One traffic-calming measure employed by the New York State Department of Transportation re-striping. Re-striping to a narrower lane slows traffic and increases the safety of the roads. What congestion might be created by this process is mitigated by the town’s restructured traffic signal timing and coordination which is based on traffic data collection. Restructured traffic signals are also meant to increase the safety of pedestrians crossing wide sections of Route 9 by increasing the time allotted. New traffic lights are to be implemented at strategic intersections where congestion and hazards typically occurs. Data collection is to be continued on the sections of the road that underwent re-striping and signal light restructuring in order to assess the effect of the measures. -

OCA Final Management Plan

Management Plan For Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park Westchester County Andrew M. Cuomo Governor Rose Harvey Commissioner Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park Management Plan Management Plan for The Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park Westchester County Prepared by The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Completed: August 31, 2016 Contacts: Linda Cooper , AICP Regional Director NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation - Taconic Park Region PO Box 308- 9 Old Post Road Staatsburg, NY 12580 (845) 889-4100 Mark Hohengasser, Park Planner NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Albany, NY 12238 (518) 408-1827 Fax: (518) 474-7013 Page 1 Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park Management Plan Page 2 Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park Management Plan Table of Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 4 List of Appendices ............................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations Used ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Management Plan - Statement of Purpose ..................................................................................................... -

Haverstraw-Ossining Ferry Unitickets Are Also Valid for Use on Transport of Rockland’S Hudson Link to Tarrytown

WEEKDAY MORNINGS VIA OSSINING STATION TO GRAND CENTRAL WEEKDAY EVENINGS VIA OSSINING STATION TO HAVERSTRAW .AM Light Face, PM Bold Face .AM Peak .AM Light Face, PM Bold Face PM Peak Haverstraw Ferry Terminal 5 53 — 6 34 — 7 09 — 7 53 — 8 41 Grand Central Terminal 3 51 4 18 4 36 4 52 5 16 5 44 6 00 6 55 7 59 Ossining1 Ferry Terminal 6 08 — 6 51 — 7 24 — 8 08 — 8 56 Harlem-125th Street 4 01 4 28 4 46 5 03 5 27 5 54 6 10 7 05 8 09 Marble Hill 4 13 4 41 — 5 15 — 6 06 — 7 18 8 22 Ossining 6 14 6 23 6 58 7 07 7 31 7 50 8 15 8 45 9 03 Yonkers 4 24 4 52 5 02 5 28 — 6 17 6 36 7 30 8 34 Tarrytown 6 23 6 31 7 08 7 16 7 40 8 00 8 24 8 54 9 13 Tarrytown 4 44 5 11 5 19 5 47 5 54 6 37 6 55 7 49 8 53 Yonkers 6 41 6 50 — 7 36 8 00 — 8 41 9 13 9 29 Ossining 4 53 5 21 5 29 5 57 6 05 6 46 7 05 7 59 9 02 Marble Hill — 7 02 — 7 47 8 11 — — 9 24 — 2 Harlem-125th Street Ossining 6 59 7 29 7 43 8 00 8 25 8 35 8 59 9 39 9 47 Ferry Terminal 4 58 — 5 34 — 6 10 — 7 10 8 04 9 07 3 Grand Central Terminal Haverstraw 7 11 7 32 7 56 8 13 8 38 8 48 9 12 9 51 9 59 Ferry Terminal 5 13 — 5 49 — 6 25 — 7 25 8 19 9 21 1 Passengers may board at Ossining for Haverstraw. -

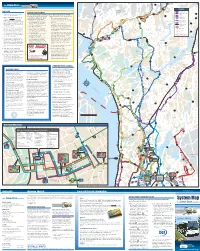

WCDOT Sysmapbrch

C C r ot on F a lls R d R D L O C V R E - L 2 L 2 S T d To Poughkeepsie To Carmel Bowl R 77 ey d d l Park-and-Ride al R R TLC V PART2 L e e n o c PART2 o k 6N v i a a l e n L W l P U l d S a o n i R n o t r w a d e d Mahopac w l S h a a c 6 c t Village r s B d O A Center R d k Hards d o R crabble R T S L L o r E V O L r E e l B l t PART2 i u t M ro p S LEGEND c S a p PUTNAM o h a Baldwin HOW TO RIDE M Rd Regular Service w 0 lo Jefferson 77 Somers COUNTY ol Place FOR YOUR SAFETY & COMFORT H Commons Lincolndale ll ki 16 Express/Limited-Stop ek s Valley 0 1. Arrive at the bus stop at least 5 minutes Pe 6 Service 202 PART2 Bee-Line buses belong to everyone, so please help us take good care of them! Shrub Oak 16 Memorial Park early to avoid missing your bus. Main St d E 12 118 Part-time Service us R 0 L itic o T 9 d v t R D To ensure the safety and comfort of all Please be courteous to those riding with you: R e N O 77 G E C l R O S D 16 Thomas Je#erson Elementary School l L l O 77 i l u b Oak k Shru S Connecting Route 2. -

MTA Metro-North Railroad Is Committed to Providing - Senior/Disabled

WEEKDAY MORNINGS VIA OSSINING STATION TO GRAND CENTRAL WEEKDAY EVENINGS VIA OSSINING STATION TO HAVERSTRAW . .AM Light Face, PM Bold Face .AM Peak .AM Light Face, PM Bold Face Early Holiday Getaway PM Peak Haverstraw 5 50 — 6 20 6 50 — 7 20 — 8 05 — 8 45 — Grand Central Terminal 2 51 3 11 3 43 4 19 4 36 4 54 5 16 A 5 57 6 22 6 28 6 52 7 25 7 57 7 59 8 33 y y Ferry Terminal l l n n o Ossining 1 Harlem-125th Street 3 01 o 3 21 3 53 4 29 4 46 5 04 5 26 A 6 08 — 6 38 7 02 7 35 8 07 8 09 8 43 9 Ferry Terminal 6 05 — 6 35 7 05 — 7 36 — 8 20 — 9 00 — 9 2 2 / / 2 Marble Hill 3 10 2 — 4 02 4 41 — 5 17 — — — 6 50 — 7 43 — 8 21 8 51 1 1 & Ossining 6 20 6 27 6 41 7 12 7 32 7 43 8 00 8 27 8 47 9 07 9 35 & 2 Yonkers 3 21 2 — 4 10 4 52 5 02 5 29 — — — 7 01 7 18 7 51 8 23 8 32 9 00 2 2 / / 2 Tarrytown 6 29 6 35 6 48 7 22 7 41 — 8 10 8 36 8 56 9 17 9 44 2 1 Tarrytown 3 40 1 3 47 4 27 5 11 5 19 5 48 5 53 A 6 34 6 58 7 20 7 30 8 08 8 40 8 51 9 17 , , 2 D 2 2 Yonkers — 6 54 7 05 — 8 02 — 8 41 — 9 15 9 27 10 00 2 / / A 1 Ossining 3 49 1 3 56 4 37 5 21 5 29 5 58 6 03 6 44 7 08 7 30 7 40 8 18 8 50 9 00 9 27 1 D 1 s Marble Hill — 7 05 7 12 — 8 13 — 8 49 — 9 26 c 9 59 10 07 s n n u Ossining 2 u R A B Harlem-125th Street 6 55 7 19 7 22 7 48 8 25 — D 8 59 9 02 9 38 9 43 10 18 4 01 R 4 01 4 42 — 5 34 — 6 08 6 49 7 17 — 7 50 8 23 8 55 — 9 32 Ferry Terminal y n r i r 3 a e Haverstraw r A B T Grand Central Terminal 7 06 7 32 7 35 8 01 8 38 8 29 8 48 9 15 9 50 9 55 10 29 Ferry Terminal F 4 16 4 16 4 57 — 5 49 — 6 24 7 04 7 32 — 8 05 8 38 9 10 — 9 47 1 Passengers may board at Ossining for Haverstraw. -

VILLAGE of OSSINING, NEW YORK COMPREHENSIVE PLAN B Village of O S S I N I N G Comprehensive Plan VILLAGE of OSSINING COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

VILLAGE OF OSSINING, NEW YORK COMPREHENSIVE PLAN B Village of O s s i n i n g Comprehensive Plan VILLAGE OF OSSINING COMPREHENSIVE PLAN VILLAGE OF OSSINING, WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK Prepared for: The Village of Ossining Prepared by: Village of Ossining Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee With: Phillips Preiss Shapiro Associates, Inc. Planning and Real Estate Consultants 434 Sixth Avenue New York, New York 10011 July 2009 Village of O s s i n i n g Comprehensive Plan I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Village of Ossining Board of Trustees Infrastructure and Transportation Sub-Committees Mayor William R. Hanauer Valerie Monastra Janis Castaldi Karen D’Attore Marlene Cheatham Reverend Stephen Holton Michael Curry Alice Joselow Susanne Donnelly Dana Levenberg Village Manager Linda G. Cooper Downtown, Waterfront and Economic Village of Ossining Department of Planning Development Sub-Committee Valerie Monastra, AICP, Village Planner Valerie Monastra Joyce M. Lannert Village of Ossining Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee Joy Solomon John Codman, III, Chair Antonio DaCruz Joyce M. Lannert, AICP, Vice Chair John W. Fried Joy Solomon, Secretary, Jerry Gershner Environmental Advisory Committee Gordon D. Albert, Former Director, Neighborhood Quality of Life Sub-Committee Interfaith Council for Action Valerie Monastra Catherine Borgia, Former Village Trustee John Codman, III Karen D’Attore Alice Joselow Antonio DaCruz Dana Levenberg John W. Fried Rose Marie Parisi Jerry Gershner, President, Greater Ossining Chamber of Commerce, Inc. In cooperation with: Reverend Stephen Holton, St. Paul’s-on-the-Hill Phillips Preiss Shapiro Associates, Inc. Episcopal Church Elizabeth Leheny, Project Director Alice Joselow, Board of Education Trustee John Shapiro, Principal-in-Charge Dana Levenberg, Board of Education Trustee Charles Starks, Zoning Specialist Linda Levine, Interfaith Council for Action, Inc.