Frank Sargeson [Norris Frank Davey], 1903 – 1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD

Intelligent, relevant books for intelligent, inquiring readers The Writing Life Twelve New Zealand Authors DEBORAH SHEPARD CANDID CONVERSATIONS WITH 12 WRITERS WHO HELPED SHAPE NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE A unique, candid and intimate survey of the life and work of 12 of our most acclaimed writers: Patricia Grace, Tessa Duder, Owen Marshall, Philip Temple, David Hill, Joy Cowley, Vincent O’Sullivan, Albert Wendt, Marilyn Duckworth, Chris Else, Fiona Kidman and Witi Ihimaera. Constructed as Q&As with experienced oral historian Deborah Shepard, they offer a marvellous insight into their careers. As a group they are now the ‘elders’ of New Zealand literature; they forged the path for the current generation. Together the authors trace their publishing and literary history from 1959 to 2018, through what might now be viewed as a golden era of publishing into the more unsettled climate of today. They address universal themes: the death of parents and loved ones, the good things that come with ageing, the components of a satisfying life, and much more. And they give advice on writing. The book has an historical continuity, showing fruitful and fascinating links $49.99 between individuals who have negotiated the same literary terrain for more than sixty years. To further honour them are magnificent photo portraits by CATEGORY: New Zealand Non Fiction distinguished photographer John McDermott, commissioned by the publisher ISBN: 978-0-9951095-3-7 for this project. eISBN: n/a ABOUT THE AUTHOR BIC: BGL, DSK, 1MBN BISAC: LCO020000, BIO007000 Deborah Shepard is an author, teacher of memoir, oral historian and film PUBLISHER: Massey University Press and art historian. -

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES

A Survey of Recent New Zealand Writing TREVOR REEVES O achieve any depth or spread in an article attempt• ing to cover the whole gamut of New Zealand writing * must be deemed to be a New Zealand madman's dream, but I wonder if it would be so difficult for people overseas, particularly in other parts of the Commonwealth. It would appear to them, perhaps, that two or three rather good poets have emerged from these islands. So good, in fact, that their appearance in any anthology of Common• wealth poetry would make for a matter of rather pleasurable comment and would certainly not lower the general stand• ard of the book. I'll come back to these two or three poets presently, but let us first consider the question of New Zealand's prose writers. Ah yes, we have, or had, Kath• erine Mansfield, who died exactly fifty years ago. Her work is legendary — her Collected Stories (Constable) goes from reprint to reprint, and indeed, pirate printings are being shovelled off to the priting mills now that her fifty year copyright protection has run out. But Katherine Mansfield never was a "New Zealand writer" as such. She left early in the piece. But how did later writers fare, internationally speaking? It was Janet Frame who first wrote the long awaited "New Zealand Novel." Owls Do Cry was published in 1957. A rather cruel but incisive novel, about herself (everyone has one good novel in them), it centred on her own childhood experiences in Oamaru, a small town eighty miles north of Dunedin -— a town in which rough farmers drove sheep-shit-smelling American V-8 jalopies inexpertly down the main drag — where the local "bikies" as they are now called, grouped in vociferous RECENT NEW ZEALAND WRITING 17 bunches outside the corner milk bar. -

March 8 2012

Vol. 22 No. 4 March 8, 2012 www.opunakecoastalnews.co.nz Published every Thursday Fortnight Phone and Fax 761-7016 A/H 761-8206 for Advertising and Editorial ISSN 1171-0624 Inside... Storms wreak havoc Knowing the Bains. A fascinating insight into the family from someone who knew them. page 2. Not happy about losing their pub. Page 7. Just one of the haysheds destroyed in the storm which swept the country last Friday night. This one was in Kina Road, Oaonui. Below all that remains of Diane and Russell Campbell’s haybarn at Pihama. We review Frank Sargeson’s Letters page 10. $270,000 raised for health centre $270,000 has been raised speaker. the room and a far from quiet of some vouchers. which excited a lot of inter- for the proposed Opunake The charity launch of the one at the front, on the stage. “That’s my favourite, be- est (No, it was not one of Health Centre with one sin- proposed health care facility The vocal auction was ably cause it is so interesting”, the items up for auction). Fiona Pears entertains gle donation of $200,000. for Opunake went off with conducted by Peter McDon- commented a man, who was Some people had their photos page 18. The remaining amount was a bang and was a night to ald of McDonald Real Estate, referring to a Roger Morris taken with the historic ‘log Gun amnesty in Eltham. raised in the charity auction remember at the Sandfords capably assisted by Sean (Remo) oil painting entitled of wood’. -

Newsletter – 20 April 2012 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 20 April 2012 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 180th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email modernletters. 1. Victoria goes to the Olympics ................................................................................. 1 2. Victoria goes to Leipzig ........................................................................................... 2 3. Write poetry! No, write short stories! No, write for children! ............................ 2 4. Resonance ................................................................................................................. 2 5. We’re probably the last to tell you, but . ........................................................... 3 6. However, we'd like to be the first to tell you about . ............................................ 3 7. The expanding bookshelf......................................................................................... 3 8. Hue & Cry and crowdfunding ................................................................................ 4 9. Congratulations ........................................................................................................ 4 10. Fiction editing mentor programme - call for applications ................................. 4 11. Poems of spirituality: call for submissions ......................................................... -

Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF MODERN LETTERS Te P¯utahi Tuhi Auaha o te Ao Newsletter – 15 April 2010 ISSN: 1178-9441 This is the 154th in a series of occasional newsletters from the Victoria University centre of the International Institute of Modern Letters. For more information about any of the items, please email [email protected]. 1. Second trimester writing courses at the IIML ................................................... 2 2. Our first PhD ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Legend of a suicide author to appear in Wellington .......................................... 2 4. The Godfather comes to town .............................................................................. 3 5. From the whiteboard ............................................................................................ 3 6. Glyn Maxwell’s masterclass ................................................................................ 3 7. This and That ........................................................................................................ 3 8. Racing colours ....................................................................................................... 4 9. New Zealand poetry goes Deutsch ...................................................................... 4 10. Phantom poetry ................................................................................................. 5 11. Making something happen .............................................................................. -

2013 ANZSI Conference: “Intrepid Indexing: Indexing Without

Intrepid indexing: indexing without boundaries 13–15 March 2013 Wellington, New Zealand Table of Contents Papers • Keynote: Intrepid indexing: from the sea to the stars, Jan Wright • Publishers, Editors and Indexers: a panel discussion, Fergus Barrowman, Mei Yen Chua and Simon Minto • Māori names and terms in indexes, texts and databases, Robin Briggs, Ross Calman, Carol Dawber • EPUB3 Indexes Charter and the future of indexing, Glenda Browne • People and place : the future of database indexing for Indigenous collections in Australia, Judith Cannon and Jenny Wood • Indexing military history, Peter Cooke • Ethics in Indexing, Heather Ebbs • Running an Indexing Business, Heather Ebbs, Pilar Wyman, Mary Coe and Tordis Flath • Archives and indexing history in the Pacific Islands, Uili Fecteau and Margaret Pointer • Typesetting Dilemmas, Tordis Flath and Mary Russell • Can an index be a work of art? Lynn Jenner and Tordis Flath • Advanced SKY Index, Jon Jermey • East Asian names: understanding and indexing Chinese, Japanese and Korean (CJK) names, Lai Lam and Cornelia (Nelly) Bess • Intermediate CINDEX - Patterns for the Plucky, Frances Lennie • Demystifying indexing: keeping the editor sane! Max McMaster (presented by Mary Russell) • Numbers in Indexing, Max McMaster (presented by Mary Russell) • Japan's indexing practice, Takashi Matsuura • Understanding Asian Names, Fiona Price • Indexing Tips and Traps; Practical approaches to improving indexes and achieving ANZSI Accreditation, Sherrey Quinn o Indexing Tip and Traps — slides o Practical -

Allegory in the Fiction of Janet Frame

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ALLEGORY IN THE FICTION OF JANET FRAME A thesis in partial fulfIlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Massey University. Judith Dell Panny 1991. i ABSTRACT This investigation considers some aspects of Janet Frame's fiction that have hitherto remained obscure. The study includes the eleven novels and the extended story "Snowman, Snowman". Answers to questions raised by the texts have been found within the works themselves by examining the significance of reiterated and contrasting motifs, and by exploring the most literal as well as the figurative meanings of the language. The study will disclose the deliberate patterning of Frame's work. It will be found that nine of the innovative and cryptic fictions are allegories. They belong within a genre that has emerged with fresh vigour in the second half of this century. All twelve works include allegorical features. Allegory provides access to much of Frame's irony, to hidden pathos and humour, and to some of the most significant questions raised by her work. By exposing the inhumanity of our age, Frame prompts questioning and reassessment of the goals and values of a materialist culture. Like all writers of allegory, she focuses upon the magic of language as the bearer of truth as well as the vehicle of deception. -

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling

The One Story and the Four Ways of Telling: The relationship between New Zealand literary autobiography and spiritual autobiography. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in English in the University of Canterbury DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UN!VEf,SITY OF c,wrrnmnw By CHRISTCHURCH, N.Z. Emily Jane Faith University of Canterbury 2001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has given various forms of support during this two year production. Thanks especially to my Mum and Dad and my brother Nick, Dylan, my friends, and my office-mates in Room 320. Somewhere between lunch, afternoon tea, and the gym, it finally got done! A special mention is due to my supervisor Patrick Evans for his faith in me throughout. The first part of my title is based on Lawrence Jones' a1iicle 'The One Story, the Two Ways of Telling, and the Three Perspectives', in Ariel 16:4 (October 1985): 127-50. CONTENTS Abst1·act ................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 I. A brief history of a brief history: New Zealand literary autobiography (and biography) ................................................................................ 2 II. The aims and procedures of this thesis ................................................... 9 III. Spiritual autobiography: the epiphany ................................................. -

The Robert Burns Fellowship 2020

THE ROBERT BURNS FELLOWSHIP 2020 The Fellowship was established in 1958 by a group of citizens, who wished to remain anonymous, to commemorate the bicentenary of the birth of Robert Burns and to perpetuate appreciation of the valuable services rendered to the early settlement of Otago by the Burns family. The general purpose of the Fellowship is to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University. It is attached to the Department of English and Linguistics of the University. CONDITIONS OF AWARD 1. The Fellowship shall be open to writers of imaginative literature, including poetry, drama, fiction, autobiography, biography, essays or literary criticism, who are normally resident in New Zealand or who, for the time being, are residing overseas and who in the opinion of the Selection Committee have established by published work or otherwise that they are a serious writer likely to continue writing and to benefit from the Fellowship. 2. Applicants for the Fellowship need not possess a university degree or diploma or any other educational or professional qualification nor belong to any association or organisation of writers. As between candidates of comparable merit, preference shall be given to applicants under forty years of age at the time of selection. The Fellowship shall not normally be awarded to a person who is a full time teacher at any University. 3. Normally one Fellowship shall be awarded annually and normally for a term of one year, but may be awarded for a shorter period. The Fellowship may be extended for a further term of up to one year, provided that no Fellow shall hold the Fellowship for more than two years continuously. -

Towards 'Until the Walls Fall Down' an Intended History of New Zealand Literature 1932-1963

Towards 'Until the walls fall down' An intended history of New Zealand Literature 1932-1963 LAWRENCE JONES Those inclusive dates point to two generations, and crucial to my intended history is the distinction Lawrence fones is Associate Professor of English at the Uni between them. The first is that of the self-appointed versity of Otago. He is the author of Barbed Wire and makers of a national literature, mostly born after 1900 Mirrors - Essays on New Zealand prose. The following and before World War I. They arrive in three waves. text was presented at a Stout Research Centre Wednesday First there is a small group beginning Seminar, on 5 October 1994. in Auckland in the mid- and late-1920s- Mason (born 1905), A.R.D. I would like first to look at the terms of my title. 'To Fairburn (1904), and, off to one side and associated wards' and 'intended' are the first operative terms. This by them with the maligned older generation, Robin seminar is given at the beginning of a process of inten Hyde (1906). Then come the Phoenix-Unicorn-Griffin sive research, and any writing beyond notes and an and the Tomorrow-Caxton groups in Auckland and outline is an intention at this point, and the outline is Christchurch, (and some of their outlying friends), something to work towards, modifying and filling in. arriving between 1932 and 1935, incorporating Fairburn Next there is 'New Zealand Literature, 1932-1963', and Mason, and including M.H . Holcroft (1902), Frank with those oddly specific dates. The first is probably Sargeson (1903), Roderick Finlayson (1904), Winston obvious enough, the publication of the Phoenix at the Rhodes (1905), E.H. -

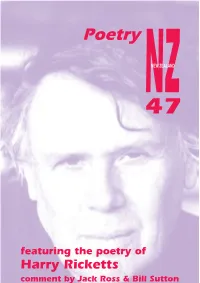

PNZ 47 Digital Version

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship Application Form 2019

The Art Foundation Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship 2019 The Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship is for an established creative writer to spend three months or more in Menton in southern France to work on a project or projects. Tihe Mauriora, e nga iwi o te motu, anei he karahipi whakaharahara. Ko te Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship tenei karahipi. Kia kaha koutou ki te tonohia mo tenei putea tautoko. Mena he tangata angitu koe i tenei karahipi, ka taea e koe haere ki te Whenua Wiwi ki te whakamahi to kaupapa, kei te mohio koe, ko te manu i kai i te matauranga nona te ao. Ko koe tena? Amount $35,000 (includes travel and accommodation) Application closing date 5:00pm, Monday 1 July, 2019 The successful applicant will become an Arts Foundation Laureate. What can you write? The residency is open to creative writers across all genres including fiction, children's fiction, poetry, creative non-fiction and playwriting. What do we cover? The residency provides: • a grant of $35,000 to cover all costs including travel to Menton, insurance, living and accommodation costs. $15,000 is paid when your itinerary and insurance is confirmed, with $10,000 payments usually made in month two and three of the residency, assuming the Fellow remains in residency through this period. • a room beneath the terrace of Villa Isola Bella is available for use as a study. Accommodation is not available at the villa. Fellows make their own accommodation arrangements, often with advice from a previous Fellow. Katherine Mansfield spent long periods at Villa Isola Bella in 1919 and 1920 after she contracted tuberculosis.