A Reexamination of the WLBT-TV Case Steven Classen George Fox University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 18-782 Released: July 27, 2018 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS FILED FOR THE TRANSFER OF CONTROL AND ASSIGNMENT OF BROADCAST TELEVISION LICENSES FROM RAYCOM MEDIA, INC. TO GRAY TELEVISION, INC., INCLUDING TOP-FOUR SHOWINGS IN TWO MARKETS, AND DESIGNATES PROCEEDING AS PERMIT-BUT-DISCLOSE FOR EX PARTE PURPOSES MB Docket No. 18-230 Petition to Deny Date: August 27, 2018 Opposition Date: September 11, 2018 Reply Date: September 21, 2018 On July 27, 2018, the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) accepted for filing applications seeking consent to the assignment of certain broadcast licenses held by subsidiaries of Raycom Media, Inc. (Raycom) to a subsidiary of Gray Television, Inc. (Gray) (jointly, the Applicants), and to the transfer of control of subsidiaries of Raycom holding broadcast licenses to Gray.1 In the proposed transaction, pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger dated June 23, 2018, Gray would acquire Raycom through a merger of East Future Group, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray, into Raycom, with Raycom surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gray. Immediately following consummation of the merger, some of the Raycom licensee subsidiaries would be merged into Gray Television Licensee, LLC (GTL), with GTL as the surviving entity. The jointly filed applications are listed in the Attachment to this Public -

Remarks and a Question-And-Answer Session With

1092 July 17 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1997 but how we're going to become one America if I had a voice like that, I could run for in the 21st century. We need your help. a third term, even though theÐ[laughter]. In September, I'm going home to Little I enjoyed meeting with your board mem- Rock to observe the 40th anniversary of the bers and JoAnne Lyons Wooten, your execu- integration of Little Rock Central High tive director, backstage. I met Vanessa Wil- School. When those nine black children were liams, who said, ``You know, I'm the presi- escorted by armed troops on their first day dent-elect; have you got any advice for me of school, there were a lot of people who on being president?'' True story. I said, ``I were afraid to stand up for them. But the do. Always act like you know what you're local NAACP, led by my friend Daisy Bates, doing.'' [Laughter] stood up for them. I want to say to you, I'm delighted to be Today, every time we take a stand that ad- joined here tonight by a distinguished group vances the cause of equal opportunity and of people from our White House and from excellence in education, every time we do the administration, including the Secretary of something that really gives economic Labor, Alexis Herman, and the Secretary of empowerment to the dispossessed, every Education, Dick Riley, and a number of oth- time we further the cause of reconciliation ers from the White House. -

LD5655.V855 1996.M385.Pdf (6.218Mb)

EDUCATING FOR FREEDOM: THE HIGHLANDER FOLK SCHOOL IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1954 TO 1964 by Jacqueline Weston McNulty Thesis submitted to the facutly of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History APPROVED: Yuu a Hayward Farrar, Chairman _ \ 4 A af 7 - “ : Lo f lA bn G UU. f Lake Ak Jo Peter Wallenstein Beverly Bunch-Ly ns February, 1996 Blacksburg, Virginia U,u LD 55S Y$55 199@ M2g5 c.2 EDUCATING FOR FREEDOM: THE HIGHLANDER FOLK SCHOOL IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, 1954 TO 1964 by Jacqueline Weston McNulty Dr. Hayward Farrar, Chairman History (ABSTRACT) This study explores how the Citizenship School Program of the Highlander Folk School shaped the grassroots leadership of the Civil Rights Movement. The thesis examines the role of citizenship education in the modern Civil Rights Movement and explores how educational efforts within the Movement enfranchised and empowered a segment of Southern black society that would have been untouched by demonstrations and federal voting legislation. Civil Rights activists in the Deep South, attempting to register voters, recognized the severe inadequacies of public education for black students and built parallel educational institutions designed to introduce black students to their rights as American citizens, develop local leadership and grassroots organizational structures. The methods the activists used to accomplish these goals had been pioneered in the mid-1950’s by Septima Clark and Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk School. Horton and Clark developed a successful curriculum structure for adult literacy and citizenship education that they implemented on Johns Island off the coast of South Carolina. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida August 30, 2021

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida August 30, 2021 The following is a report on the status of communications services in geographic areas impacted by Hurricane Ida as of August 30, 2021 at 11:00 a.m. EDT. This report incorporates network outage data submitted by communications providers to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Disaster Information Reporting System (DIRS). Note that the operational status of communications services during a disaster may evolve rapidly, and this report represents a snapshot in time. The following counties are in the current geographic area that is part of DIRS (the “disaster area”) for today’s report. Alabama: Baldwin, Clarke, Conecuh, Escambia, Mobile, Monroe, Washington. Louisiana: Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Evangeline, Iberia, Iberville, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lafourche, Livingston, Orleans, Plaquemines, Point Coupee, St, Martin, St, Mary, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Terrebonne, Vermillion, Washington, West Baton Rouge, West Feliciana. Mississippi: Adams, Alcorn, Amite, Attala, Benton, Bolivar, Calhoun, Carroll, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Claiborne, Clay, Coahoma, Copiah, DeSoto, Forrest, Franklin, George, Greene, Grenada, Hancock, Harrison, Hinds, Holmes, Humphreys, Issaquena, Itawamba, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lamar, Lee, Leflore, Lincoln, Madison, Marion, Marshall, Monroe, Montgomery, Panola, Pearl River, Perry, Pike, Pontotoc, Prentiss, Quitman, Sharkey, Stone, Sunflower, Tallahatchie, Tate, Tippah, Tishomingo, Tunica, Union, Walthall, Warren, Washington, Webster, Wilkinson, Yalobusha, Yazoo. 1 911 Services The Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau (PSHSB) learns the status of each Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) through the filings of 911 Service Providers in DIRS, reporting to the FCC’s Public Safety Support Center, coordination with state 911 Administrators and, if necessary, direct contact with individual PSAPs. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

WLOX Station Manager Jackson, Mississippi

Message Page 1 of 5 Lisa Fowlkes Testimony Before FCC Regional Hearing March 7, 2006 Dave Vincent/ WLOX Station Manager Jackson, Mississippi Hurricane Katrina, on August 29th 2005, is said to have been the worst natural disaster in our country’s history. Looking at the devastation in our state and in neighboring states we can agree with that statement. When most residents of America hear about Mississippi they think of a rural state with not much of a population base. However the population of the Mississippi Gulf Coast is close to the population of the city of New Orleans. The 2003 census information put the population along the Mississippi Gulf Coast at 411,000. While the population of the city of New Orleans was slightly higher than 484,000. While the Mississippi Gulf Coast has not gotten the media attention of New Orleans I think the numbers show that we do have a large population base which has a great need to be informed prior to and after a major catastrophe. You will be glad to hear that Mississippi broadcasters, both television and radio, did an outstanding job. In several cases, the broadcasters put their lives on the line in order to make sure the viewing or listening public had the necessary information to weather the storm. There were some problems that I would like to address today for you and others to consider whether there might be some national help to address these concerns. But first let me talk about the amazing job broadcasters did. At my own television station, WLOX-TV in Biloxi, Mississippi we started our around the clock coverage early on Sunday morning. -

Emmett Till & the Modernization of Law

Saint Louis University School of Law Scholarship Commons All Faculty Scholarship 2009 The ioleV nt Bear it Away: Emmett iT ll & the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi Anders Walker Saint Louis University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/faculty Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Anders, The ioV lent Bear it Away: Emmett iT ll & the Modernization of Law Enforcement in Mississippi (October 27, 2008). San Diego Law Review, Vol. 46, p. 459, 2009. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE VIOLENT BEAR IT AWAY EMMETT TILL & THE MODERNIZATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT IN MISSISSIPPI ∗ ANDERS WALKER ABSTRACT Few racially motivated crimes have left a more lasting imprint on American memory than the death of Emmett Till. Yet, even as Till’s murder in Mississippi in 1955 has come to be remembered as a catalyst for the civil rights movement, it contributed to something else as well. Precisely because it came on the heels of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, Till’s death convinced Mississippi Governor James P. Coleman that certain aspects of the state’s handling of racial matters had to change. Afraid that popular outrage over racial violence might encourage federal intervention in the region, Coleman removed power from local sheriffs, expanded state police, and modernized the state’s criminal justice apparatus in order to reduce the chance of further racial violence in the state. -

Mississippi: Is This America? (1962-1964) ROY WILKINS

Mississippi: Is This America? (1962-1964) ROY WILKINS: There is no state with a record that approaches that of Mississippi in inhumanity, murder and brutality and racial hatred. It is absolutely at the bottom of the list. NARRATOR: In 1964, the state of Mississippi called it an invasion. Civil rights workers called it Freedom Summer. To change Mississippi and the country, they would risk beatings, arrest, and their lives. FANNY CHANEY: You all know what my child is doing? He was trying for us all to make a better living. And he had two fellows from New York, had their own home and everything, didn't have nothing to worry, but they come here to help us. Did you all know they come here to help us? They died for us. UNITA BLACKWELL: People like myself, I was born on this river. And I love the land. It's the delta, and to me it's now a challenge, it's history, it's everything, to what black people it's all about. We came about slavery and this is where we acted it out, I suppose. All of the work, all them hard works and all that. But we put in our blood, sweat and tears and we love the land. This is Mississippi. WHITE HUNTER: I lived in this delta all my life, my parents before me, my grandparents. I've hunted and fished this land since I was a child. This land is composed of two different cultures, a white culture and a colored culture, and I lived close to them all my life. -

Your Automated 2 Hour Report

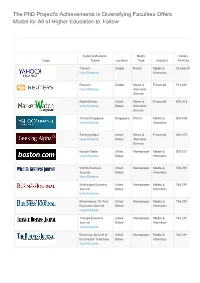

The PhD Project's Achievements in Diversifying Faculties Offers Model for All of Higher Education to Follow Outlet or Website Media Visitors Logo Name Location Type Industry Per Day Yahoo! Global Portal Media & 78,665,00 View Release Information Reuters Global News & Financial 753,831 View Release Information Service MarketWatch United News & Financial 676,072 View Release States Information Service Yahoo! Singapore Singapore Portal Media & 605,608 View Release Information Seeking Alpha United News & Financial 386,872 View Release States Information Service Boston Globe United Newspaper Media & 300,021 View Release States Information Wichita Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Washington Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Minneapolis / St. Paul United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release Triangle Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Business Journal of United Newspaper Media & 186,291 the Greater Triad Area States Information View Release Tampa Bay Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release St. Louis Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release South Florida United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release Puget Sound United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release San Jose Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal -

The Benevolence Post

PENUMBRA THEATRE COMPANY PRODUCTION Est. 1976 February 12 to March 10 Price 15¢ THE BENEVOLENCE POST Skeptics By IFA BEYZA I was a child of the civil rights movement…integrated when I was nine years old, but I didn't encounter Emmett Till's story until I was a teenager. The Till Trilogy [The Ballad of Emmett Till, benevolence, That Summer in Sumner] is inspired by the story of a 14-year-old youth from Chicago who journeys to Mississippi in August of 1955. This trip to visit family in Mississippi certainly changes his fate. He's murdered in that week, and his life-death-journey changes the course of the nation ... I wanted to look at this story from an advantage point of view. The Till saga was a highly documented case. It was like a national soap opera on race. It was played out in the newspapers in the North, in the South, the black press and the white press. There was a tremendous amount of information available to the public. You would think that, because there was so much information, the truth or facts of the actual story would be readily available. What I found was, even as I researched the archive of primary documentation, was a host of confusing and inaccurate information. There were a lot of holes in the accounting of details, that didn't quite seem to make sense to me. So, that was the first lesson which I will share with you: “even if it's in print, even if it's documented, even if it's supposed to be from an expert, you must approach that information with skepticism.” Because the only truth that you have is that it's printed and that it's representing the tone as truth, but that's not necessarily the case. -

With Determination and Fortitude We Come to Vote: Black Organization and Resistance to Voter Suppression in Mississippi

WITH DETERMINATION AND FORTITUDE 195 With Determination and Fortitude We Come to Vote: Black Organization and Resistance to Voter Suppression in Mississippi by Michael Vinson Williams On July 2, 1946, brothers Medgar and Charles Evers, along with four friends, decided they would vote in their hometown of Decatur, Missis- sippi. Both brothers had registered without incident but when the men returned to cast their ballots they were met by a mob of armed whites. The confrontation grew in intensity with each step toward the polling place. After a few nerve-racking moments of yelling and shoving, the Evers group retreated, but the harassment did not end. Medgar Evers recalled that while they were walking away some of the whites followed them and that one man in a 1941 Ford “leaned out with a shotgun, keep- ing a bead on us all the time and we just had to walk slowly and wait for him to kill us …. They didn’t kill us but they didn’t end it, either.” The African American men went home, retrieved guns of their own, and returned to the polling station but decided to leave the weapons in the car. The white mob again prevented them from entering the voting precinct, and the would-be voters gave up.1 1 This article makes use of the many newspaper clippings catalogued in the Allen Eugene Cox Papers housed at the Mitchell Memorial Library Special Collections Department at Mississippi State University (Starkville) and the Trumpauer (Joan Harris) Civil Rights Scrapbooks Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson, Mississippi.