On Restructuring the Nyc Health+Hospitals Corporation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

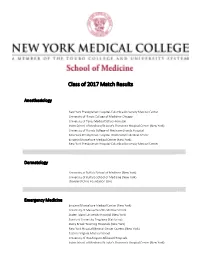

2017 Match Day Results by Program

Class of 2017 Match Results Anesthesiology New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia University Medical Center University of Illinois College of Medicine-Chicago University of Texas Medical School-Houston Icahn School of Medicine/St Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center (New York) University of Florida College of Medicine-Shands Hospital New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center (New York) New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia University Medical Center Dermatology University at Buffalo School of Medicine (New York) University of Buffalo School of Medicine (New York) Cleveland Clinic Foundation (OH) Emergency Medicine Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center (New York) University of Massachusetts Medical School Staten Island University Hospital (New York) Stanford University Programs (California) Stony Brook Teaching Hospitals (New York) New York Hospital Medical Center Queens (New York) Eastern Virginia Medical School University of Washington Affiliated Hospitals Icahn School of Medicine/St Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center (New York) University of Connecticut School of Medicine Rhode Island Hospital/Brown University Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (North Carolina) Icahn School of Medicine/St Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center (New York) Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center (New York) Oregon Health and Science University Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (New Hampshire) Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center (New York) University of Washington Affiliated Hospitals Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center -

2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Survey

COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT 2019 To all New Yorkers: As New York City’s public health care system, our goal is to empower you to live your healthiest life. Clinical care starts with you and your health care team, but we recognize that many factors impact your health beyond medical care alone – a safe home environment, space to be physically active, access to fresh food, even exposure to daily stress and poor social well-being can impact your health outcomes. To assess and prioritize the greatest health needs of the neighborhoods and communities we serve, NYC Health + Hospitals conducted a comprehensive and inclusive process to complete this Community Health Needs Assessment for 2019. The findings represent the voices of the patients we serve, clinical experts and community partners, and are backed by quantitative data analysis. Recognizing that the health needs of patients coming through our hospital doors may not represent the wider health needs of the community, we embarked on an extensive stakeholder engagement process led by OneCity Health, who built new relationships with community stakeholders through the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program. For the first time, we conducted a system-wide assessment to identify priorities that need to be addressed city-wide and will allow us to maximize our resources in response. We believe that we should reliably deliver high-quality services and that patients should have a consistent experience at our facilities. Since our 2016 assessment, we have worked tirelessly to address significant health needs of the community and to make it easier for our patients to access our services: • We opened and renovated dozens of community-based health centers to expand access to primary and preventive care. -

MGCRB FFY 2022 Individual Decisions

MGCRB FFY 2022 Individual Decisions Case Provider's Home Requested CBSA Number Case Name Priority CBSA Code Code Request Status 22C0001 Reid Health (15-0048) Primary Request 15 34620 Approved Secondary Request 15 34620 Dismissed Tertiary Request 15 17140 Dismissed 22C0003 Beaumont Hospital Dearborn (23-0020) Primary Request 19804 47664 Approved Secondary Request 19804 11460 Dismissed Tertiary Request 19804 19804 Dismissed 22C0004 Saint Thomas DeKalb Hospital (44-0148) Primary Request 44 34980 Approved 22C0005 Saint Thomas River Park Hospital (44-0151) Primary Request 44 34980 Approved 22C0006 Lake Charles Memorial Hospital (19-0060) Primary Request 29340 13140 Approved 22C0008 Bayhealth Hospital, Sussex Campus (08-0009) Primary Request 41540 20100 Approved 22C0009 Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (31-0038) Primary Request 35154 35614 Approved 22C0010 Texoma Medical Center (45-0324) Primary Request 43300 19124 Approved Secondary Request 43300 43300 Dismissed 22C0011 Memorial Hospital (36-0156) Primary Request 36 45780 Approved 22C0012 Northeast Alabama Regional Medical Center (01-0078) Primary Request 11500 12060 Approved Secondary Request 11500 13820 Dismissed 22C0013 Scripps Mercy Hospital (05-0077) Primary Request 41740 41740 Approved 22C0014 Scripps Green Hospital (05-0424) Primary Request 41740 41740 Approved 22C0018 Reid Health (15-0048) Primary Request 15 17140 Withdrawn (Pre-Decision) 22C0019 Onslow Memorial Hospital (34-0042) Primary Request 27340 48900 Approved Secondary Request 27340 35100 Dismissed 22C0020 Lenoir Memorial -

CMO Update, Spring 2021

CMO A PUBLICATION FOR TBHC PHYSICIANSUPDATE AND COMMUNITY PARTNERS SPRING 2021 A Message from Dr. Kondamudi – Vasantha Kondamudi, MD, Chief Medical Officer In our last fall issue, I looked back on the COVID spring surge, how our clinicians and all of TBHC stepped up to the challenges, and the lessons we learned. This issue, I am so relieved and happy to report that I’m focusing on the future. And the future means the COVID-19 vaccine. Most of you know that the Pfizer vaccine (what TBHC is administering) is 95% effective after two doses and has gotten high marks for safety. You can access the Pfizer published trial at: https:// www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 We also now have the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Join these physicians below, just some of many who got vaccinated. Pratibha “Prat” Vemulapalli, MD, Sylvie de Souza, MD, Chair, Chair, Surgery Leonard Berkowitz, MD, Chief, Infectious Diseases Emergency Medicine Nabil Mesiha, MD, Attending, Pulmonary Sumeet Bahl, MD, Attending, Vascular and Interventional Radiology Introducing The Brooklyn Cancer Center New York Cancer & Blood Specialists (NYCBS), one of the leading oncology practices in the nation, has partnered with The Brooklyn Hospital Center (TBHC), to create a new comprehensive cancer care program, The Brooklyn Cancer Center. NYCBS is a leading practice in the national OneOncology partnership, the network of independent community oncology practices. With access to OneOncology technology, integration support and capital, NYCBS provides access to cutting-edge oncology care, including clinical trial research across Brooklyn. A new facility is planned for the end of 2021, but the community does not have to wait for the excellent care this partnership provides. -

Advertisement for NYC Health + Hospitals FEMA Program Request for Qualifications for the Provision of Construction Contractor Services

Advertisement for NYC Health + Hospitals FEMA Program Request for Qualifications for the Provision of Construction Contractor Services New York City Economic Development Corporation (“NYCEDC”), on behalf of the projects’ construction manager (“CM”), is seeking qualified firms for the construction of the Major Work project at Coney Island Hospital, 2601 Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11235. Due its location, Coney Island Hospital (“CIH”) is vulnerable to extreme coastal storms and in October 2012, the facility suffered extensive flood damage because of Superstorm Sandy. Since then, the hospital has temporarily restored the damaged areas and, working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”), have developed plans to mitigate damage from future storms and flooding. NYCEDC, as the lead of an interagency team, is now focused on the Major Work project. The construction of the Coney Island Hospital campus project includes the following components: • Build a new resilient acute care hospital tower to be known as the Critical Services Structure (“CSS”); • Provide on-site parking, • Demolition of existing buildings, including Hammett Pavilion, Building 6, and various existing site improvements; • Renovation and selective demolition of 60,000 gross sq. feet including portions of the existing Main Building and Tower Building; and • Build a new permanent flood mitigation structure (s) (e.g. flood wall) around the campus. NYCEDC has contracted with NBBJ to lead the design effort for all contract documents associated with the Services. Turner/McKissack, -

New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation

NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION Bronx Kings County Hospital Center Metropolitan Hospital Center Jacobi Medical Center 451 Clarkson Avenue 1901 First Avenue 1400 Pelham Parkway South Brooklyn, New York 11203 New York, New York 10029 Bronx, New York 10461 718-245-3131 212-423-6262 212-918-5000 Woodhull Medical and Mental Renaissance Health Care Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center Network Diagnostic Health Center 760 Broadway & Treatment Center 234 East 149th Street Brooklyn, New York 11206 215 West 125th Street Bronx, New York 10451 718-963-8000 New York, New York 10027 718-579-5000 212-932-6500 Manhattan Morrisania Diagnostic Bellevue Hospital Center Queens & Treatment Center 462 First Avenue Elmhurst Hospital Center 1228 Gerard Avenue New York, New York 10016 79-01 Broadway Bronx, New York 10452 212-562-4141 Elmhurst, New York 11373 718-960-2777 Coler Goldwater Specialty 718-334-4000 North Central Bronx Hospital Hospital Queens Hospital Center 3424 Kossuth Avenue Roosevelt Island 82-70 164th Street Bronx, New York 10467 New York, New York 10044 Jamaica, New York 11432 718-519-5000 212-848-6000 718-883-3000 Segundo Ruiz Belvis Diagnostic Gouverneur Healthcare Services & Treatment Center 227 Madison Street Staten Island 545 East 142nd Street New York, New York 10002 Sea View Hospital Bronx, New York 10454 212-238-7000 Rehabilitation Center & Home 718-579-4000 460 Brielle Avenue Harlem Hospital Center Staten Island, New York 10314 506 Lenox Avenue Brooklyn 718-317-3000 New York, New York 10037 Coney Island Hospital 212-939-1000 2601 Ocean Parkway Brooklyn, New York 11235 718-616-30000 Cumberland Diagnostic & Treatment Center 100 North Portland Avenue Brooklyn, New York 11205 718-260-7500 Dr. -

Jacobi Medical Center

. June 10, 2015 Dear Manufacturers, I am writing on behalf of Jacobi Medical Center, 340B ID DSH330127, to inform manufacturers that Jacobi Medical Center recently underwent an audit by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of Jacobi Medical Center’s compliance with 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B) requirements. As background, Jacobi Medical Center qualified for the 340B Program as a Disproportionate Share Hospital at 1400 Pelham Parkway South, Bronx, New York 10461 and has participated in the 340B Program since 1992. Through the audit process, Jacobi Medical Center was found to have non-compliance within their 340B Program and responsible for repayment as a result of the following findings: Jacobi Medical Center dispensed 340B drugs to ineligible providers, as prohibited by 42 USC 256b(a)(5)(B). The sample revealed that Jacobi’s contract pharmacies deemed two prescriptions 340B-eligible even though they should not have been eligible. The prescriptions were written by providers at ineligible sites (private offices which were not reimbursable on Jacobi’s Medicare cost report) without an arrangement demonstrating that responsibility of care provided remained at Jacobi. In addition, the auditor found that the 12 month eligibility period did not screen the patient-provider relationship or the patient referral process. It was also noted that the electronic medical record system did not update the billing software, thus allowing the third party pharmacy benefits manager to consider deactivated providers as eligible prescribers. Jacobi Medical Center reversed the 2 prescriptions from contract pharmacies that should not have been eligible, and removed the ineligible providers from Jacobi medical Center’s list of eligible providers. -

New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy the Spring Course

New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy The Spring Course: Best of DDW 2021 Saturday, June 5, 2021 8:00 am – 3:15 pm Virtual Event The Spring Course: Best of DDW 2021 is jointly provided by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center and the New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Page 1 of 10 Course Description The Spring Course is devoted to a review of the most compelling topics discussed during Digestive Disease Week® 2021. Faculty will present critically important information on new drugs, the etiology and pathophysiology of disease states, the epidemiology of diseases, the medical, surgical and endoscopic treatment of disease, and the social impact of disease states pertaining to gastroenterology, endoscopy, and liver disease. The program includes a video forum of new endoscopic techniques as well as a summary of the major topics presented at the most important academic forum in gastroenterology, making for an invaluable educational experience for those who were unable to attend Digestive Disease Week® and an excellent summary review for all others. Learning Objectives • Discuss the spectrum of gastrointestinal diseases such as motility disorders and colorectal cancer and outline the enhancement and effectiveness of related treatment options such as the use of artificial intelligence in the detection and resection of polyps during colonoscopy • Evaluate advances in the methods of assessing disease status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and discuss the application of these techniques -

Cornell University Official Publication

CORNELL UNIVERSITY OFFICIAL PUBLICATION Volume XXVIII Number I Announcement of The Medical College for 1936-37 at 1300 York Avenue, New York City and the first year, also, at Ithaca, N. Y. Ithaca, New York Published by the University July 1, 1936 Printed by W. F. Humphrey Press Inc. Geneva, N. Y. CONTENTS PAGE Calendar _ 5 Board of Trustees . 6 New York Hospital-Cornell Medical College Association . 7 Medical College Council . 7 Officers of Administration . .8 and . Executive Faculty Committees of the Faculty . 9 and Faculty Teaching Staff. 10 New York Hospital Staff . 27 Bellevue Hospital, Staff of Second Division . 38 Memorial Hospital Staff 40 General Statement . 43 Requirements for Admission .... 48 Admission to Advanced Standing . 49 Requirements for Promotion and Graduation ......50 General Information:. .52 Fees, Scholarships, Loans, Prizes. 52 Educational Policy and Description of Courses: . 56 Summary of Hours in Medical Course . 58 Anatomy .... 59 Applied Pathology and Bacteriology . 67 Bacteriology 64 Biochemistry . 62 Legal Medicine 83 Medicine and Medical Specialties. 67 72 Obstetrics and Gynecology 64 Pathology . Pediatrics 74 Pharmacology 66 Physiology 63 Psychiatry. 75 81 Public Health and Preventive Medicine 3 PAGE and Surgery Surgical Specialties ... 77 . ... 82 Radiology . Schedule of Courses . ..... 84 Special Students . .....88 The Graduate School . .... 89 The Ithaca Division: of 91 Faculty Medicine at Ithaca . 92 University Calendar . 92 General Statement . Plan of Instruction 94 Anatomy . 94 Histology and Embryology 96 Physiology and Biochemistry . 97 Summarized Statement . ... 99 General Information . 100 Schedule of Instruction . 102 Combined A.B. and M.D. Degrees . 102 Graduate Work at Ithaca .... 104 Internship Appointments ..... ... 106 Register of Students, 1936-1937 . -

![NYSNA Pension Plan New Participant Information • (877) RN BENEFITS [762-3633] • Rnbenefits.Org](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2994/nysna-pension-plan-new-participant-information-877-rn-benefits-762-3633-rnbenefits-org-242994.webp)

NYSNA Pension Plan New Participant Information • (877) RN BENEFITS [762-3633] • Rnbenefits.Org

NYSNA Pension Plan New Participant Information • (877) RN BENEFITS [762-3633] • rnbenefits.org Defined benefit plan • Once a participant has completed five years of credited service, that participant will be VESTED and upon retirement will receive a monthly pension benefit for the rest of his/her life. Employer makes all contributions • RN contributes nothing Portable between more than 30 participating facilities in the New York City area (see back) How the pension benefit is calculated • Mathematical formula that recognizes earnings (base salary and experience differential only) and years of credited service • Based on the highest final average earnings for any five complete calendar years during the last 10 years of covered employment immediately before termination 3 retirement options to choose from For more detailed information on these options, please refer to your Welcome to the Pension Plan folder Normal retirement starting at age 65 Early retirement (unreduced) Must retire from active covered employment between the ages of 60 and 64 and have at least 20 years of credited service Early retirement Must retire between the ages of 55 and 64 (reduced by 1/2% for each month that early retirement precedes normal retirement at age 65) The information contained herein should not be viewed as a substitute for the Plan document, the most recent Summary Plan Description, and any relevant Summary of Material Modifications. In case of discrepancies or contradictions, the language and terms of the Plan document, the SPD, and SMMs shall prevail. 9/2020 Deferred Vested Benefit • Available to participants who are vested and leave the Plan prior to being eligible for retirement reductions • Payable at Normal Retirement age 65 with no reductions or between age 55 and 64 with early retirement reductions The Preretirement Survivor Benefit • If a vested participant dies before she/he retires • If married, the spouse is automatically the beneficiary. -

Network Review | SUMMER/FALL 2008 Edition SUMMER/FALL 2008 Edition | Network Review

NNetworketwork ReviewReview Building for Success SUMMER/FALL 2008 Edition Harlem Hospital Center Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center Metropolitan Hospital Center Morrisania Neighborhood Family Health Center Renaissance Health Care Network Segundo Ruiz Belvis Neighborhood Family Health Center 4BSBI+POFT "OJUB4POJ .% -JODPMO)PTQJUBM.FEJDBM%JSFDUPS3JDIBSE,4UPOF .% .FUSPQPMJUBO)PTQJUBM.FEJDBM%JSFDUPS.FSZM 8FJOCFSH .FUSPQPMJUBO)PTQJUBM&YFDVUJWF%JSFDUPS'SPOUSPX%S"ZNBO&M.PIBOEFT LFZOPUFTQFBLFS4S7JDF Sarah Jones’ performance brought the 1SFTJEFOU +PTn34gODIF[ ))$1SFTJEFOU"MBO%"WJMFTBOE$IBSMZOO(PJOT $IBJSQFSTPO ))$#PBSEPG%JSFDUPST audience to a standing ovation. 5)"//6"-63#"/ )&"-5)$0/'&3&/$& 4)08$"4&%.0%&-40'*/5&37&/5*0/ continues on pg. 11 453"5&(*&4"/%#&4513"$5*$&4 1BSUOFSTIJQT As racial and ethnic disparities in workshops with participants from New CAB/Auxiliary Network Annual Dinner healthcare outcomes continue to make York, Texas and California and focused headlines both locally and nationally, on specific health disciplines that have the 7th Annual Conference on Urban garnered measurable successes in Health brought together healthcare treatment modalities. professionals and other stakeholders to share innovative strategies aimed The clinical expertise of our Network at eliminating such inequalities in hospitals and Neighborhood Family health. The forum, held on June 12th Health Centers was prominently and 13th at the Helmsley Park Lane showcased during the workshops. continues on pg. 12 Hotel in Manhattan, featured clinical continues on pg. 11 Network Review | SUMMER/FALL 2008 Edition SUMMER/FALL 2008 Edition | Network Review &NCSBDJOH$IBOHF Welcome to the 2008 Summer/Fall Please join me in wishing Metropolitan of 15,000 square feet including 37 exam Edition of our Network Newsletter. This the best in their future endeavors. -

Careconnect Facilities

CareConnect Facilities Manhattan Hospitals Yale-New Haven Northern Harlem Westchester Bridgeport Metropolitan Lenox Hill Manhattan Eye, Ear & Throat Phelps Memorial Lenox Health Greenwich Greenwich Montefiore White Plains Village Medical Bellevue Centers Peconic Bay Medical Center North Central Bronx Jacobi Huntington Glen Cove Lincoln Syosset North Shore University Zucker Hillside Plainview Elmhurst LIJ Medical Center Cohen Children’s LIJ Forest Nassau University Hills Queens Medical Center Southside Woodhull Wyckoff Heights South Oaks Kings County LIJ Valley Stream Staten Island Maimonides University (North) Coney Island Staten Island University (South) For a searchable list of CareConnect’s providers, visit CareConnect.com/providersearch Hospitals • Bellevue Hospital Center, 462 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016, P: 212-562-4141 • Bridgeport Hospital, 267 Grant St, Bridgeport, CT 06610, P: 203-688-8412 • Coney Island Hospital, 2601 Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11235, P: 718 616-3000 • Elmhurst Hospital Center, 79-01 Broadway, Elmhurst, NY, 11373, P: 718-334-4000 • Glen Cove Hospital, 101 St. Andrews Lane, Glen Cove, NY 11542, P: 516-674-7540 • Greenwich Hospital, 5 Perryridge Road, Greenwich, CT 06 830, P: 203-688-8412 • Harlem Hospital Center, 506 Lenox Avenue, New York, NY 10037, P: 212-939-1000 • Huntington Hospital, 270 Park Avenue, Huntington, NY 11743, P: 631-351-2000 • Jacobi Medical Center, 1400 Pelham Parkway South, Bronx, NY 10461, P: 718-918-5000 • Kings County Hospital Center, 451 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11203, P: 718-245-3131