Vadym Kholodenko, Piano Friday, October 12, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 1 (2016 9) 41-54 ~ ~ ~ УДК 78.085 The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel Valentina V. Bass* Krasnoyarsk State Institute of Art 22 Lenin Str., Krasnoyarsk, 660049, Russia Received 19.07.2015, received in revised form 21.08.2015, accepted 30.08.2015 The article deals with the key issue of modern musicology, the issue of a certain genre that prevails in the works of a music composer, an ability of a genre to become a factor that determines stylistic specificity. In the works of Maurice Ravel this style-forming factor is dance. On the example of the minuet that occupies a special place in the works of the composer, the article explores the principles of mediation of choreographic and musical features of the dance prototype at the semantic and structural levels in the thematism and form generation of Ravel’s works. The aesthetic perfection and delicate elegance of gestures, graphical precision of choreographic pattern and dialogueness typical for the minuet have been reflected in the motive-composition character of the thematism, the periodicity of the syntax, the relative stability of the meter, the active use of various methods of polyphonization of the musical texture, the exclusive role of the principle of symmetry on the compositional, melodic and textural levels of the musical form. Individual features of the minuet in various works of Ravel are related to their stylistic origins and genre fusion creating certain imagery. Keywords: minuet, dance prototype, choreographic pattern of dance, genre semantics, counter rhythm, figurative polyphony, stylistic multilayers. -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

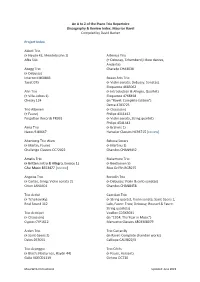

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

Menuet from Sonatine Maurice Ravel Transcribed for Violin and Piano Sheet Music

Menuet From Sonatine Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Violin And Piano Sheet Music Download menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4071 times and last read at 2021-09-27 14:22:05. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of menuet from sonatine maurice ravel transcribed for violin and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Violin Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Menuet From Sonatine 1905 By Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Flute And Piano Menuet From Sonatine 1905 By Maurice Ravel Transcribed For Flute And Piano sheet music has been read 3015 times. Menuet from sonatine 1905 by maurice ravel transcribed for flute and piano arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 03:53:13. [ Read More ] Mouvement De Menuet From Sonatine By Maurice Ravel Mouvement De Menuet From Sonatine By Maurice Ravel sheet music has been read 6722 times. Mouvement de menuet from sonatine by maurice ravel arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 10:04:05. [ Read More ] Maurice Ravel Menuet Sur Le Nom De Haydn Complete Version Maurice Ravel Menuet Sur Le Nom De Haydn Complete Version sheet music has been read 3455 times. -

“Preludes” a New Musical by Dave Malloy Inspired by the Music of Sergei Rachmaninoff Developed with and Directed by Rachel Chavkin

LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE EISA DAVIS, GABRIEL EBERT, NIKKI M. JAMES, JOSEPH KECKLER, CHRIS SARANDON, AND OR MATIAS, ON PIANO TO BE FEATURED IN THE LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “PRELUDES” A NEW MUSICAL BY DAVE MALLOY INSPIRED BY THE MUSIC OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF DEVELOPED WITH AND DIRECTED BY RACHEL CHAVKIN SATURDAY, MAY 23 THROUGH SUNDAY, JULY 19 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JUNE 15 AT THE CLAIRE TOW THEATER REHEARSALS BEGIN TODAY, APRIL 21 Eisa Davis, Gabriel Ebert, Nikki M. James, Joseph Keckler, Chris Sarandon, and Or Matias, on piano, begin rehearsals today for the LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater production of PRELUDES, a new musical by Dave Malloy, inspired by the music of Sergei Rachmaninoff, developed with and directed by Rachel Chavkin. PRELUDES, a world premiere and the first musical to be produced by LCT3 in the Claire Tow Theater, begins performances Saturday, May 23, opens Monday, June 15, and will run through Sunday, July 19 at the Claire Tow Theater (150 West 65th Street). From the creators of Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812, PRELUDES is a musical fantasia set in the hypnotized mind of Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. After the disastrous premiere of his first symphony, the young Rachmaninoff (to be played by Gabriel Ebert) suffers from writer’s block. He begins daily sessions with a therapeutic hypnotist (to be played by Eisa Davis), in an effort to overcome depression and return to composing. PRELUDES was commissioned by LCT3 with a grant from the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation. Paige Evans is Artistic Director/LCT3. -

French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel

Studies in Pianistic Sonority, Nuance and Expression: French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel Iwan Llewelyn-Jones Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy School of Music Cardiff University 2016 Abstract This thesis traces the development of Maurice Ravel’s pianism in relation to sonority, nuance and expression by addressing four main areas of research that have remained largely unexplored within Ravel scholarship: the origins of Ravel’s pianism and influences to which he was exposed during his formative training; his exploration of innovative pianistic techniques with particular reference to thumb deployment; his activities as performer and teacher, and role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works; his place in the French pianistic canon. Identifying the main research questions addressed in this study, an Introduction outlines the dissertation content, explains the criteria and objectives for the performance component (Public Recital) and concludes with a literature review. Chapter 1 explores the pianistic techniques Ravel acquired during his formative training, and considers how his study of specific works from the nineteenth-century piano repertory shaped and influenced his compositional style and pianism. Chapter 2 discusses Ravel’s implementation of his idiosyncratic ‘strangler’ thumbs as articulators of melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and textural material in selected piano works. Ravel’s role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works as disseminated to succeeding generations of pianists is addressed in Chapter 3, while Chapters 4 and 5 evaluate Ravel’s impact upon twentieth-century French pianism through considering how leading French piano pedagogues and performers responded to his trailblazing piano techniques. -

MARTHA ARGERICH Recorded Concerts & Recitals Previous Update: January 23, 2017 This Update: February 23, 2017

MARTHA ARGERICH Recorded Concerts & Recitals Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: January 23, 2017 This Update: February 23, 2017 New entries for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals I have and others I am aware of. Excerpts are not included. For commercially issued items I have only listed what I have or would be delighted to have. Comments, additions and corrections are welcome.Details of Argerich CDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/Argerich.html Please contact me by e-mail: [email protected] LOGO: ** = I have the original issue; * = I have a CD-R/DVD±R copy of the original issue; SACD = Super Audio CD; BD = Blu-Ray; (LD) = Laserdisc; (PTA) = I have a Privately Taped Audio Recording; (PTV) = I have a Privately Taped Video Recording BACALOV, L. Astoriando 17/3/2010 - Rome - Bacalov - (PTA) 14/5/2011 - Oita - Hubert - Argerich’s Meeting Point AMP-1101 (2CD)** 19-25/10/2012 - Rosario (Argentina) - Rivera - Cosentino SC 1271-4 (4CD)** 19-25/10/2012 - Rosario (Argentina) - Rivera - Cosentino SC 1271-4 (4CD)** Portena for Two Pianos and Orchestra 10/6/2015 - Lugano - Hubert, O. della Svizzera italiana/Vedernikov - Warner 2564628549 (3CD) 17/7/2015 - Buenos Aires - Hubert, O. S. Nacional/Bacalov - (PTV) BACH, J.S. Concerto for Four Pianos and Strings in a, BWV 1065 22/7/2003 - Verbier - Kissin, Levine, Pletnev - Birthday Festival O. - RCA 82876 60942 9 (DVD)** 15/10/2004 - Buenos Aires - Sebastiani, Vallina, Balat - Sinfonietta Argerich/Ntaca - 3rd mvt encored - (PTA) 12/3/2012 - Athens - Kapelis, Maisky, Mogilevsky - Megaron Camerata/Korsten - (PTV) 21/10/2013 - Paris - Lim, Zilberstein, Vallina - Chamber O. -

Preparing Students for Works of Debussy and Ravel

The Impressionist Style: Preparing Students for Works of Debussy and Ravel Curtis Pavey Introduction The piano music of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel is regarded highly as some of the most imaginative and beautiful music for the instrument. Pianists frequently enjoy these works for their unique harmonic language, dramatic virtuosity, and use of tonal color. That said, studying works by these two composers is often an uphill battle for even advanced pianists; the challenging musical language and the stringent technical requirements demand a refined musician with a good sense of pianistic control. The purpose of this article is to suggest some teaching strategies to use with late intermediate and early advanced level pianists. I have broken down my discussion into two parts – musical difficulties and technical difficulties – offering a broad sense of the types of challenges a student who is unfamiliar with this music will face. By making this music more accessible and understandable, we can make the learning process less frustrating and more enjoyable. Before Ravel and Debussy Before a student encounters works by Debussy and Ravel, I would recommend acquainting them with the impressionist style via works by composers of today. Numerous composers, such as Catherine Rollins, Jennifer Lin, and Dennis Alexander, have composed pedagogical works for students who are at the beginning or intermediate level. Using these from the beginning of a student’s study of the piano helps to build musical and technical fluency before introducing the easier works of Debussy and Ravel, which are only appropriate for students at the upper intermediate level or higher. -

Maurice Ravel Chronology

Maurice Ravel Chronology by Manuel Cornejo 2018 English Translation by Frank Daykin Last modified date: 10 June 2021 With the kind permission of Le Passeur Éditeur, this PDF, with some corrections and additions by Dr Manuel Cornejo, is a translation of: Maurice Ravel : L’intégrale : Correspondance (1895-1937), écrits et entretiens, édition établie, présentée et annotée par Manuel Cornejo, Paris, Le Passeur Éditeur, 2018, p. 27-62. https://www.le-passeur-editeur.com/les-livres/documents/l-int%C3%A9grale In order to assist the reader in the mass of correspondence, writings, and interviews by Maurice Ravel, we offer here some chronology which may be useful. This chronology attempts not only to complete, but correct, the existent knowledge, notably relying on the documents published herein1. 1 The most recent, reliable, and complete chronology is that of Roger Nichols (Roger Nichols, Ravel: A Life, New Haven, Yale University, 2011, p. 390-398). We have attempted to note only verifiable events with documentary sources. Consultation of many primary sources was necessary. Note also the account of the travels of Maurice Ravel made by John Spiers on the website http://www.Maurice Ravel.net/travels.htm, which closed down on 31 December 2017. We thank in advance any reader who may be able to furnish us with any missing information, for correction in the next edition. Maurice Ravel Chronology by Manuel Cornejo English translation by Frank Daykin 1832 19 September: birth of Pierre-Joseph Ravel in Versoix (Switzerland). 1840 24 March: birth of Marie Delouart in Ciboure. 1857 Pierre-Joseph Ravel obtains a French passport. -

Ravel Biography.Pdf

780.92 R2528g Goss Bolero, the life of Maurice Ravel, Kansas city public library Kansas city, missouri Books will be issued only on presentation of library card. Please report lost cards and change of residence promptly. Card holders are responsible for all books, records, films, pictures or other library materials checked out on their cards. 3 1148 00427 6440 . i . V t""\ 5 iul. L-* J d -I- (. _.[_..., BOLERO THE LIFE OF MAURICE .RAVEL '/ ^Bpofas fay Madeleine Goss : BEETHOVEN, MASTER MUSICIAN DEEP-FLOWING BROOK: The Story of Johann Sebastian Bach (for younger readers) BOLERO : The Life of Maurice Ravel Maurice Ravel, Manuel from a photograph by Henri BOLERO THE LIFE OF MAURICE RAVEL BY MADELEINE GOSS "De la musique avant toute chose, De la musique encore et toujours." Verlaine NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY Wfti^zsaRD UNIVERSITY PRESS COPYRIGHT, IQ40, BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY, INC. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA '.'/I 19 '40 To the memory of my son ALAN who, in a sense, inspired this work CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Bolero 1 II. Childhood on the Basque Coast . 14 III. The Paris Conservatory in Ravel's Time 26 IV. He Begins to Compose .... 37 V. Gabriel Faure and His Influence on Ravel 48 VI. Failure and Success .... 62 VII. Les Apaches 74 VIII. The Music of Debussy and Ravel . 87 IX. The "Stories from Nature" ... 100 X. The Lure of Spain 114 XL Ma Mere VOye 128 XII. Daphnis and Chloe 142 XIII. The "Great Year of Ballets" ... 156 XIV. Ravel Fights for France ...