Preparing Students for Works of Debussy and Ravel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Harmony and Timbre in Maurice Ravel's Cycle Gaspard De

Miljana Tomić The role of harmony and timbre in Maurice Ravel’s cycle Gaspard de la Nuit in relation to form A thesis submitted to Music Theory Department at Norwegian Academy of Music in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master’s in Applied Music Theory Spring 2020 Copyright © 2020 Miljana Tomić All rights reserved ii I dedicate this thesis to all my former, current, and future students. iii Gaspard has been a devil in coming, but that is only logical since it was he who is the author of the poems. My ambition is to say with notes what a poet expresses with words. Maurice Ravel iv Table of contents I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Preface ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Presentation of the research questions ..................................................................... 1 1.3 Context, relevance, and background for the project .............................................. 2 1.4 The State of the Art ..................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................ 8 1.6 Thesis objectives ........................................................................................................ 10 1.7 Thesis outline ............................................................................................................ -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

A Study of Ravel's Le Tombeau De Couperin

SYNTHESIS OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION: A STUDY OF RAVEL’S LE TOMBEAU DE COUPERIN BY CHIH-YI CHEN Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University MAY, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music ______________________________________________ Luba-Edlina Dubinsky, Research Director and Chair ____________________________________________ Jean-Louis Haguenauer ____________________________________________ Karen Shaw ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to several individuals without whose support I would not have been able to complete this essay and conclude my long pursuit of the Doctor of Music degree. Firstly, I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Luba Edlina-Dubinsky, for her musical inspirations, artistry, and devotion in teaching. Her passion for music and her belief in me are what motivated me to begin this journey. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Jean-Louis Haguenauer and Dr. Karen Shaw, for their continuous supervision and never-ending encouragement that helped me along the way. I also would like to thank Professor Evelyne Brancart, who was on my committee in the earlier part of my study, for her unceasing support and wisdom. I have learned so much from each one of you. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Mimi Zweig and the entire Indiana University String Academy, for their unconditional friendship and love. They have become my family and home away from home, and without them I would not have been where I am today. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

Le Tombeau De Couperin I

27 Season 2016-2017 Thursday, November 10, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 11, at 2:00 Saturday, November 12, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Benjamin Beilman Violin Westminster Symphonic Choir Joe Miller Director Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin I. Prélude II. Forlane III. Menuet IV. Rigaudon ProkofievViolin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 19 I. Andantino—Andante assai II. Scherzo: Vivacissimo III. Moderato Intermission Ravel Daphnis and Chloé (complete ballet) This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. LiveNote™, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. The November 10 concert is sponsored by Kay and Harry Halloran. The November 12 concert is sponsored by Mr. and Mrs. Peter Shaw. The Philadelphia Orchestra acknowledges the presence of the Hermann Family at the November 11 concert, with gratitude for their donation, made in memory of Myrl Hermann, of a C.G. Testore violin (ca. 1700). Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit WRTI.org to listen live or for more details. 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and impact through Research. is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues The Orchestra’s award- orchestras in the world, to discover new and winning Collaborative renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture Learning programs engage sound, desired for its its relationship with its over 50,000 students, keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home families, and community hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, members through programs audiences, and admired for and also with those who such as PlayINs, side-by- a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area sides, PopUP concerts, innovation on and off the performances at the Mann free Neighborhood concert stage. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 1 (2016 9) 41-54 ~ ~ ~ УДК 78.085 The Genre of the Minuet in the Works of Maurice Ravel Valentina V. Bass* Krasnoyarsk State Institute of Art 22 Lenin Str., Krasnoyarsk, 660049, Russia Received 19.07.2015, received in revised form 21.08.2015, accepted 30.08.2015 The article deals with the key issue of modern musicology, the issue of a certain genre that prevails in the works of a music composer, an ability of a genre to become a factor that determines stylistic specificity. In the works of Maurice Ravel this style-forming factor is dance. On the example of the minuet that occupies a special place in the works of the composer, the article explores the principles of mediation of choreographic and musical features of the dance prototype at the semantic and structural levels in the thematism and form generation of Ravel’s works. The aesthetic perfection and delicate elegance of gestures, graphical precision of choreographic pattern and dialogueness typical for the minuet have been reflected in the motive-composition character of the thematism, the periodicity of the syntax, the relative stability of the meter, the active use of various methods of polyphonization of the musical texture, the exclusive role of the principle of symmetry on the compositional, melodic and textural levels of the musical form. Individual features of the minuet in various works of Ravel are related to their stylistic origins and genre fusion creating certain imagery. Keywords: minuet, dance prototype, choreographic pattern of dance, genre semantics, counter rhythm, figurative polyphony, stylistic multilayers. -

May, 1952 TABLE of CONTENTS

111 AJ( 1 ~ toa TlE PIANO STYI2 OF AAURICE RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Jack Lundy Roberts, B. I, Fort Worth, Texas May, 1952 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFLLUSTRTIONS. Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIANO STYLE ... II. RAVEL'S MUSICAL STYLE .. # . , 7 Melody Harmony Rhythm III INFLUENCES ON RAVEL'S EIANO WORKS . 67 APPENDIX . .* . *. * .83 BTBLIO'RAWp . * *.. * . *85 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Jeux d'Eau, mm. 1-3 . .0 15 2. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), mm. la-3 .r . -* - -* . 16 3. Le Paon (Histoires Naturelles), 3 a. « . a. 17 4. Ondine (Gaspard de a Nuit), m. 1 . .... 18 5. Ondine (Gaspard de la Nuit), m. 90 . 19 6. Sonatine, first movement, nm. 1-3 . 21 7. Sonatine, second movement, 22: 8. Sonatine, third movement, m m . 3 7 -3 8 . ,- . 23 9. Sainte, umi. 23-25 . * * . .. 25 10. Concerto in G, second movement, 25 11. _Asi~e (Shehdrazade ), mm. 6-7 ... 26 12. Menuet (Le Tombeau de Coupe rin), 27 13. Asie (Sh6hlrazade), mm. 18-22 . .. 28 14. Alborada del Gracioso (Miroirs), mm. 43%. * . 8 28 15. Concerto for the Left Hand, mii 2T-b3 . *. 7-. * * * .* . ., . 29 16. Nahandove (Chansons Madecasses), 1.Snat ,-5 . * . .o .t * * * . 30 17. Sonat ine, first movement, mm. 1-3 . 31 iv Figure Page 18. Laideronnette, Imperatrice des l~~e),i.......... Pagodtes (jMa TV . 31 19. Saint, mm. 4-6 « . , . ,. 32 20. Ondine (caspard de la Nuit), in. 67 .. .4 33 21. -

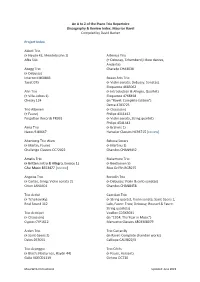

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms