Henry Kolm by Brandon Bies and Sam Swersky May 7 & 8, 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate History Spanning the Past 17,000 Years at the Bottom of a South Island Lake

VOL. 98 NO. 10 OCT 2017 Lakebed Cores Record Shifting Winds Cell Phone App Aids Irrigation Earth & Space Science News Red/Blue and Peer Review A New Clue about CO2 UPTAKE Act Now to Save on Registration and Housing Early Registration Deadline: 3 November 2017, 11:59 P.M. ET Housing Deadline: 15 November 2017, 11:59 P.M. ET fallmeeting.agu.org Earth & Space Science News Contents OCTOBER 2017 PROJECT UPDATE VOLUME 98, ISSUE 10 12 Shifting Winds Write Their History on a New Zealand Lake Bed A team of scientists finds a year-by-year record of climate history spanning the past 17,000 years at the bottom of a South Island lake. PROJECT UPDATE 18 Growing More with Less Using Cell Phones and Satellite Data Researchers from the University of Washington and Pakistan are using 21st-century technology to revive farming as a profitable profession in the Indus 24 Valley. OPINION COVER Red/Blue Assessing a New Clue 10 and Peer Review Healthy skepticism has long formed the to How Much Carbon Plants Take Up foundation of the scientific peer review Current climate models disagree on how much carbon dioxide land ecosystems take up process. Will anything substantively new be for photosynthesis. Tracking the stronger carbonyl sulfide signal could help. gleaned from a red team/blue team exercise? Earth & Space Science News Eos.org // 1 Contents DEPARTMENTS Editor in Chief Barbara T. Richman: AGU, Washington, D. C., USA; eos_ [email protected] Editors Christina M. S. Cohen Wendy S. Gordon Carol A. Stein California Institute Ecologia Consulting, Department of Earth and of Technology, Pasadena, Austin, Texas, USA; Environmental Sciences, Calif., USA; wendy@ecologiaconsulting University of Illinois at cohen@srl .caltech.edu .com Chicago, Chicago, Ill., José D. -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Wemher Von (Braun Rr'eam Q'ri6ute Vnveifino Ceremony

Wemher von (Braun rr'eam q'ri6ute Vnveifino Ceremony July 3, 2010 5:00 p.m. )fpo{[o Courtyartf vs. Space ~ qu,c~t Center rrfiose wfio are fionored . .. WILHELM ANGELE HELMUT HOELZER EBERHARD REES ERICH BALL OSCAR HOLDERER KARL REILMANN OSCAR BAUSCHINGER HELMUT HORN GERHARD REISIG HERMANN BEDUERFTIG HANS HOSENTHIEN WERNER ROSINSKI RUDOLF BEICHEL HANS HUETER LUDWIG ROTH ANTON BEIER WALTER JACOBI HEINRICH ROTHE HERBERT BERGELER RICHARD JENKE WILHELM ROTHE JOSEF BOEHM HEINZKAMPMEIER ARTHUR RUDOLPH MAGNUS VON BRAUN ERICH KASCHIG FRIEDRICH VON SAURMA THEODOR BUCHHOLD ERNST KLAUSS HEINZ SCHARNOWSKI WALTER BUROSE FRITZ KRAEMER MARTIN SCHILLING WERNERDAHM HERMANN KROEGER RUDOLF SCHLIDT KONRAD DANNENBERG HUBERTKROH ALBERT SCHULER GERDDEBEEK GUSTAV KROLL HEINRICH SCHULZE KURT DEBUS WILLI KUBERG WILLIAM SCHULZE FRIEDRICH DOHM WERNER KUERS FRIEDRICH SCHWARZ GERHARD DRAWE ERNST LANGE ERNST SEILER FRIEDRICH DUERR HANS LINDENMAYR KARLSENDLER OTTO EISENHARDT KURT LINDNER WERNER SIEBER HANS FICHTNER HERMANN LUDEWIG FRIEDTJOF SPEER ALFRED FINZEL HANNES LUEHRSEN ARNOLD STEIN EDWARD FISCHEL CARL MANDEL WOLFGANG STEURER HERBERT FUHRMANN ERICH MANTEUFEL ERNST STUHLINGER ERNST GEISSLER HANSMAUS BERNHARD TESSMANN WERNER GENGELBACH HANSMILDE ADOLPH THIEL DIETERGRAU HEINZ MILLINGER GEORG VON TIES EN HAUSEN HANS GRUENE RUDOLF MINNING WERNER TILLER WALTER HAEUSSERMANN WILLIAM MRAZEK JOHANNES TSCHINKEL KARL HAGER FRITZ MUELLER JULIUS TUEBBECKE GUENTHER HAUKOHL ERICH NEUBERT ARTHUR URBANSKI ARNOHECK MAX NOWAK FRITZ VANDERSEE KARL HEIMBURG ROBERT PAETZ WERNER VOSS EMIL HELLEBRAND HANS PALAORO THEODORVOWE GERHARD HELLER KURTPATT FRITZ WEBER BRUNO HELM HANS PAUL HERMANN WEIDNER ALFRED HENNING FRITZ PAULI WALTER WIESMAN BRUNO HEUSINGER HELMUT PFAFF ALBIN WITTMANN OTTO HIRSCHLER THEODOR POPPEL HUGO WOERDEMANN OTTO HOBERG WILLIBALD PRASTHOFER ALBERT ZEILER RUDOLF HOELKER WILHELM RAITHEL HELMUT ZOIKE Wem6er von (}Jraun 'Team 'Tri6ute VnveiCing Ceremony July 3,2010 5:00p.m. -

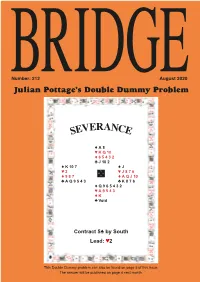

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

PEENEMUENDE, NATIONAL SOCIALISM, and the V-2 MISSILE, 1924-1945 Michael

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ENGINEERING CONSENT: PEENEMUENDE, NATIONAL SOCIALISM, AND THE V-2 MISSILE, 1924-1945 Michael Brian Petersen, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Dissertation Directed By: Professor Jeffrey Herf Departmen t of History This dissertation is the story of the German scientists and engineers who developed, tested, and produced the V-2 missile, the world’s first liquid -fueled ballistic missile. It examines the social, political, and cultural roots of the prog ram in the Weimar Republic, the professional world of the Peenemünde missile base, and the results of the specialists’ decision to use concentration camp slave labor to produce the missile. Previous studies of this subject have been the domain of either of sensationalistic journalists or the unabashed admirers of the German missile pioneers. Only rarely have historians ventured into this area of inquiry, fruitfully examining the history of the German missile program from the top down while noting its admi nistrative battles and technical development. However, this work has been done at the expense of a detailed examination of the mid and lower -level employees who formed the backbone of the research and production effort. This work addresses that shortcomi ng by investigating the daily lives of these employees and the social, cultural, and political environment in which they existed. It focuses on the key questions of dedication, motivation, and criminality in the Nazi regime by asking “How did Nazi authori ties in charge of the missile program enlist the support of their employees in their effort?” “How did their work translate into political consent for the regime?” “How did these employees come to view slave labor as a viable option for completing their work?” This study is informed by traditions in European intellectual and social history while borrowing from different methods of sociology and anthropology. -

C:\My Documents\Adobe

American Contract Bridge League Presents Beached in Long Beach Appeals at the 2003 Summer NABC Plus cases from the 2003 Open and Women’s USBC Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................... iii The Expert Panel ................................................ v Cases from Long Beach Tempo (Cases 1-11) .......................................... 1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 12-20) ......................... 38 Misinformation (Cases 19-31).................................. 60 Other (Cases 32-37) ........................................ 107 Cases from U.S. Open and Women’s Bridge Championships (Cases 38-40) . 122 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists ......................... 138 Closing Remarks From the Editor ................................. 141 Advice for Advancing Players.................................... 143 NABC Appeals Committee ...................................... 144 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMW Appeal Without Merit Warning BIT Break in Tempo CoC Conditions of Contest CC Convention Card LA Logical Alternative MP Masterpoints MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always our goal is to inform, provide constructive criticism and stimulate change (that is hopefully for the better) in a way that is instructive and entertaining. At NABCs, appeals from non-NABC+ -

Beat Them at the One Level Eastbourne Epic

National Poetry Day Tablet scoring - the rhyme and reason Rosen - beat them at the one level Byrne - Ode to two- suited overcalls Gold - time to jump shift? Eastbourne Epic – winners and pictures English Bridge INSIDE GUIDE © All rights reserved From the Chairman 5 n ENGLISH BRIDGE Major Jump Shifts – David Gold 6 is published every two months by the n Heather’s Hints – Heather Dhondy 8 ENGLISH BRIDGE UNION n Bridge Fiction – David Bird 10 n Broadfields, Bicester Road, Double, Bid or Pass? – Andrew Robson 12 Aylesbury HP19 8AZ n Prize Leads Quiz – Mould’s questions 14 n ( 01296 317200 Fax: 01296 317220 Add one thing – Neil Rosen N 16 [email protected] EW n Web site: www.ebu.co.uk Basic Card Play – Paul Bowyer 18 n ________________ Two-suit overcalls – Michael Byrne 20 n World Bridge Games – David Burn 22 Editor: Lou Hobhouse n Raggett House, Bowdens, Somerset, TA10 0DD Ask Frances – Frances Hinden 24 n Beat Today’s Experts – Bird’s questions 25 ( 07884 946870 n [email protected] Sleuth’s Quiz – Ron Klinger’s questions 27 n ________________ Bridge with a Twist – Simon Cochemé 28 n Editorial Board Pairs vs Teams – Simon Cope 30 n Jeremy Dhondy (Chairman), Bridge Ha Ha & Caption Competition 32 n Barry Capal, Lou Hobhouse, Peter Stockdale Poetry special – Various 34 n ________________ Electronic scoring review – Barry Morrison 36 n Advertising Manager Eastbourne results and pictures 38 n Chris Danby at Danby Advertising EBU News, Eastbourne & Calendar 40 n Fir Trees, Hall Road, Hainford, Ask Gordon – Gordon Rainsford 42 n Norwich NR10 3LX -

BULLETIN Editorial

THE INTERNATIONAL BRIDGE PRESS ASSOCIATION Editor: John Carruthers This Bulletin is published monthly and circulated to around 400 members of the International Bridge Press Association comprising the world’s leading journalists, authors and editors of news, books and articles about contract bridge, with an estimated readership of some 200 million people BULLETIN who enjoy the most widely played of all card games. www.ibpa.com No. 561 Year 2011 Date October 10 President: PATRICK D JOURDAIN 8 Felin Wen, Rhiwbina Editorial Cardiff CF14 6NW, WALES UK Bridge has truly hit the big time. No, I do not mean bridge has been admitted to the (44) 29 2062 8839 Olympic Games. However, bridge is now listed on at least two sports betting sites! [email protected] The sites are PAF, www.paf.com/betting, an organisation with offices in Finland, Chairman: Sweden, Estonia and Spain, and Unibet, a Spanish betting site resident in Malta at PER E JANNERSTEN https://es.unibet.com/betting and the Bermuda Bowl is the game. Italy is, no surprise, Banergatan 15 SE-752 37 Uppsala, SWEDEN the favourite at 2:1; on both sites USA1 is next at 13:4 and 4:1 respectively. Sweden, (46) 18 52 13 00 The Netherlands and Poland are listed at 15:2, 8:1 17:2 on PAF and all three are at [email protected] 15:2 on Unibet; USA2 is at 10:1 and 15:1 respectively; Brazil and Israel are at 12:1 Executive Vice-President: on both sites and Bulgaria is at 15:1. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number One Hundred and Fifty-Seven January 2016 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month, all the hands revolve around pre-emptive openings. Take careful note of the vulnerability and position of the pre-emptor, and use it to assess how strong you should be or how strong your partner might be. BRIDGEYou are West in the auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and 4-card majors. 1. Dealer West. Game All. 4. Dealer North. Game All. 7. Dealer South. Love All. 10. Dealer North. Love All. ♠ 9 ♠ 7 6 ♠ K Q 2 ♠ A Q 7 6 ♥ Q 4 3 N ♥ A K 4 N ♥ A K 7 6 5 4 N ♥ Q 8 5 3 N W E W E W E ♦ K J W E ♦ A K 4 ♦ K Q 2 ♦ 8 3 2 S S S ♣ J 8 7 6 5 4 3 S ♣ 8 7 6 5 4 ♣ 7 ♣ A 6 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South ? Pass 3♠ Pass 3♣ 3♦ Dbl Pass ? ? ? 2. Dealer West. N/S Game. 5. Dealer East. Love All. 8. Dealer South. Love All. 11. Dealer North. Love All. ♠ A Q 8 7 6 4 3 2 ♠ K J 7 6 5 ♠ A 4 2 ♠ J 7 5 4 3 N N N ♥ 7 6 ♥ K Q 3 2 ♥ 9 8 ♥ J 6 5 4 N W E W E W E ♦ 5 4 ♦ A K 3 ♦ A K Q 7 6 5 ♦ 7 3 W E S S S ♣ 2 ♣ 3 ♣ A 6 ♣ Q 7 S West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South ? 3♣ Pass 3♠ 3♦ 3NT Pass ? ? ? 3. -

Robert "Bob" Hamman President and Founder

Robert "Bob" Hamman President and Founder When he's not competing in national and international bridge tournaments, Bob Hamman - ranked the world's top bridge player in 1983, and from 1985 through 2004 - can be found inventing new promotional sweepstakes and gaming contests, and developing the mathematical models used to rate the risks and analyze the odds associated with large money promotions. Hamman, who founded SCA Promotions in 1986, has built the company into the world's largest provider of prize coverage for promotions, contests and games. He is behind many of the million dollar challenges seen at nationally televised sporting events, as well as the online lotteries and sweepstakes that have transformed the promotional industry in recent years. He has planted a $500,000 promotional prize in a Hershey's bar, guaranteed the performance bonuses of professional golfers and race car drivers, and covered prizes in fishing tournaments, fast-food restaurant chain contests, consumer products, scratch-and-win campaigns, casino jackpots, bingo, radio and television contests and even an olive-in-one toss into a martini. Prior to launching SCA Promotions, Hamman managed his own insurance brokerage firm, Hamman Group Insurance Services Inc. He has also spent the past four decades working as a professional bridge player. Arguably the best known name in bridge, Hamman has won 12 world championships, over 50 national championships and was named American Contract Bridge League (ACBL) player of the year three times. He was inducted into the ACBL Hall of Fame in 1999. A native of Los Angeles, Hamman moved to Dallas in 1969 when Ira Corn hired him to play on his professional bridge team, the Aces, which brought the world championship back to the U.S. -

Marshall Space Flight Center

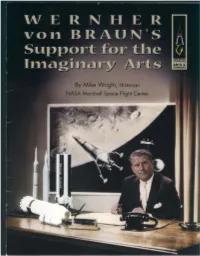

............__........ Marshall Space Flight Center Introduction This booklet, prepared by the Marshall Space Flight Center, is illustrative of the Center's support for the von Braun Celebration of the Arts and Sciences (VBCAS). Marshall is honored to be a participant in the celebration of this 50-year cultural and technological legacy of Dr. Wernher von Braun and the members of his famed German rocket team. The VBCAS features a year-long series of events, performances, exhibits and historical, cultural and educational programs. Special performances by internationally known artists and speakers, and commemorative events featuring an aerospace, German, or nostalgic theme will be held during this year-long celebration. More than 30 arts, technology, educational and community organizations have been working for almost three years to plan this series of events. In 1950, Dr. von Braun and approximately 100 of his team members came to Huntsville, Alabama, to begin work on what would later become America's historic space program. Dr. von Braun eventually served as the first director of the Marshall Center and led the development of the Saturn V launch vehicle that lofted three American astronauts on their journey to the moon in July 1969. music. In the 1920s, von Braun was accepted for led the piano lessons by the great composer Paul design for the most powerful rocket the world has Hindemith and had even composed some pieces of ever known and used it to launch the first humans his own by the age of 15. Von Braun also took cello to the surface of the moon in 1969.