Letter Written by Bryan Woolnough MBE, 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List at £18.00 Saving £10 from the Full Published Price

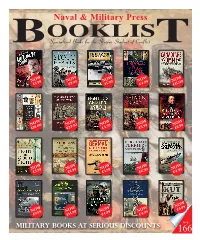

Naval & Military Press Specialised Books for the Serious Student of Conflict NOW £5.99 NOW £9.99 NOW £5.99 NOW NOW £4.99 £18.00 NOW NOW £15.00 £27.50 NOW £4.99 NOW NOW £3.99 £5.99 NOW NOW £6.99 £6.99 NOW £3.99 NOW NOW £6.99 £9.99 military books at serious discounts NOW NOW £4.99 £14.99 NOW £4.99 NOW £4.99 NOW £6.99 166Issue A new “Westlake” classic A Guide to The British Army’s Numbered Infantry Regiments of 1751-1881 Ray Westlake An oversized 127 page softback published by The Naval & Military Press, September 2018. On Early Bird offer with this Booklist at £18.00 saving £10 from the full published price. Order No: 27328. This book, the first in a series of British Army ‘Guides’, deals with the numbered regiments that existed between 1751, when the British infantry was ordered to discard their colonels’ names as titles and be known in future by number only (1st Regiment of Foot, 2nd Regiment of Foot, etc), and 1881 when numerical designations were replaced by the now familiar territorial names such as the Hampshire Regiment or Middlesex Regiment. The book provides the formation date of each regiment, names of colonels prior to 1751, changes of title, battle honours awarded before 1881 and brief descriptions of uniform and badges worn. Helpful to the collector will be the badge authorisation dates included. With a view to further research, details of important published regimental histories have been noted. The numbering of infantry regiments reached 135 but, come the reforms of 1881, only 109 were still in existence. -

Liberation: the Canadians in Europe Issued Also in French Under Title: La Libération

BILL McANDREW • BILL RAWLING • MICHAEL WHITBY LIBERATION TheLIBERATION Canadians in Europe ART GLOBAL LIVERPOOL FIRST CANADIAN ARMY MANCHESTER IRE NORTH-WEST EUROPE 1944-1945 ENGLAND NORTH SEA BIRMINGHAM Cuxhaven Northampton WILHELMSHAVEN BARRY EMDEN BRISTOL OXFORD THAMES S OLDENBURG UXBRIDGE WESER Iisselmeer D BREMEN LONDON Frinton SALISBURY ALDERSHOT Amsterdam N LYME REGIS D OW Bridport GUILDFORD NS THE HAGUE FALMOUTH PLYMOUTH AMERSFOORT A ALLER SOUTHAMPTON D O REIGATE SEVENOAKS W Rotterdam N MARGATE RIJN L PORTSMOUTH S Crawley NEDER WORTHING CANTERBURY R ISLE Portslade FOLKESTONE E OF Shoreham DOVER H ARNHEM RYE FLUSHING T MINDEN WIGHT Peacehaven N E EMS MAAS NIJMEGEN NEWHAVEN Hastings HERTOGENBOSCH HANOVER OSTEND WESE Erle Lembeck E N G L I S H C CALAIS DUNKIRK BRUGES H A N Wesel R N E L STRAITS OF DOVERBoulogne ANTWERP EINDHOVEN RHINE Hardelot HAMM YPRES GHENT VENLO THE HAZEBROUCK RUHR Lippstadt ARMENTIERES BRUSSELS B München-Gladbach DÜSSELDORF Cherbourg ROER E LE TREPORT St. Valery-en-Caux ABBEVILLE Jülich SOMME L Aachen COLOGNE DIEPPE Düren G MEUSE Le Havre BREST AMIENS I Rouen GERMANY CAEN U N O LISIEUX St. Quentin Remagen B ST. MALO R M M R A SEINE N L I AVRANCHES ORNE D JUNE 1940 Y U T FALAISE X AISNE E T OISE SEDAN M NANTES- B A GASSICOURT O F R A N C E U R N G TRIER Mainz RENNES RHEIMS Y ALENCON PARIS LAVAL MOSELLE RHINE CHARTRES CHATEAUBRIANT LE MANS Sablé-sur-Sarthe ST. NAZAIRE Parcé LO BILL MCANDREW BILL RAWLING MICHAEL WHITBY Commemorative Edition Celebrating the 60th Anniversary of the Liberation of the Netherlands and the End of the Second World War in Europe Original Edition ART GLOBAL Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data for first edition: McAndrew, Bill, 1934- Liberation: The Canadians in Europe Issued also in French under title: La Libération. -

Royal Engineers Journal

ISSN 0035-8878 THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Volume 95 JUNE 1981 No. 2 THE COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS (Established 1875, Incorporated by Royal Charter, 1923) Patron-HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN President Major-General M E Tickell, CBE, MC, MA, C Eng, FICE ...................... 1979 Vice-Presiden ts Brigadier D L G Begbie, OBE, MC, BSc, C Eng, FICE ......................... 1980 Major General G B Sinclair, CBE, FIHE ................................. .... 1980 Elected Members Colonel B AE Maude, MBE, MA .................................. 1965 Major J M Wyatt, RE .............................................. 1978 Lieut-Colonel R M Hutton, MBE, BSc, C Eng, FICE, MIHE ............. 1978 Brigadier D J N Genet, MBIM ..................................... 1979 Colonel A H W Sandes, MA, C Eng, MICE .......................... 1979 Colonel G A Leech, TD, C Eng, FIMunE, FIHE ....................... 1979 Major J W Ward, BEM, RE ........................................ 1979 Captain W S Baird, RE ............................................ 1979 Lieut-Colonel C C Hastings, MBE, RE ............................... 1980 Lieut-Colonel (V) P E Williams, TD ................................ 1980 Brigadier D H Bowen, OBE ....................................... 1981 Ex-Officio Members Brigadier R A Blomfield, MA, MBIM .................................... D/E-in-C Colonel K J Marchant, BSc, C Eng, MICE ................................ AAG RE Brigadier A C D Lloyd, MA ..................................... -

The 10Th Indian Division in the Italian Campaign, 1944-45: Training, Manpower

THE 10TH INDIAN DIVISION IN THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN, 1944-45: TRAINING, MANPOWER AND THE SOLDIER’S EXPERIENCE By MATTHEW DAVID KAVANAGH A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA BY RESEARCH, HISTORY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This dissertation will observe the capabilities and experience of the Indian Army in the Second World War, by examining the 10th Indian Division’s campaign in Italy. The focus will be on three themes of the division’s deployment to Italy; its training, manpower and the experience of the Indian soldier. Whilst these themes are part of the wider historiography of the Indian Army; there has been no significant study of these topics in relation to Italy, which this work seeks to redress. Observing the division’s training and manpower will indicate its capabilities during the Second World War. How did the Indian Army maintain an expeditionary force far from its home base, given the structural weaknesses in its recruitment and organisation? Did the Indian Army’s focus on the war in Japan, and jungle warfare, have a detrimental effect on the training of troops deployed to Italy? The reforms that the Indian Army, made to its training and organisation were critical in overcoming the difficulties that arose from campaigning in Italy. -

Yearbook-2020-Online-Edition.Pdf

Yearbook 2020 The Journal of The Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces PEGASUS Yearbook 2020 – The Journal of The Parachute Regiment & Airborne Forces The Parachute Regiment Charter “What manner of men are these who wear the maroon red beret? They are firstly all volunteers, and are then toughened by hard physical training. As a result they have that infectious optimism and that offensive eagerness which comes from physical well being. They have jumped from the air and by doing so have conquered fear. Their duty lies in the van of the battle: they are proud of this honour and have never failed in any task. They have the highest standards in all things, whether it be skill in battle or smartness in the execution of all peace time duties. They have shown themselves to be as tenacious and determined in defence as they are courageous in attack. They are, in fact, men apart – every man an Emperor.” Field Marshal The Viscount Montgomery of Alamein The Past The Future The Regimental Charter The Parachute Regiment was formed These special capabilities are The Parachute Regiment provides the to provide the infantry arm of the demanded more than ever in an capability to deploy an infantry force Airborne formations raised during evolving operational environment at short notice, in the vanguard of the Second World War, in order to where complexity, ambiguity and operations and in the most demanding deliver a specialised operational confusion abound. The requirement of circumstances. Paratroopers have capability. Airborne forces were for speedy, preventive deployments two unique roles: they are trained and required to operate at reach, with a is still paramount, where airborne ready to form the spearhead of the light logistic footprint, often beyond soldiers may have to operate at the Army’s rapid intervention capability; traditional lines of support. -

The Urban Battle of Ortona

THE URBAN BATTLE OF ORTONA by Jayson Geroux B.A. Degree (Honours History), Wilfrid Laurier University, 1993 A thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor(s): Lee Windsor, PhD, History Examining Board: Cindy Brown, PhD, History David Hofmann, PhD, Sociology This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK September, 2020 © Jayson Geroux, 2020 Abstract This thesis closely examines 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade’s day-by-day decisions and combat actions during the urban battle for Ortona in December 1943. Ortona stands among the most famous historical cases of urban warfare that have been harvested for lessons and doctrinal formulas for modern armies. Existing histories reveal how the story is often simplified into glimpses of its most dramatic moments that are seldom cross-referenced or connected chronologically. This study links the tangled nest of dramatic stories in time and space to reveal the chain of historical cause and consequence. Additionally, this study considers how geography, force composition, weapons systems, and the presence of substantial numbers of Italian civilians all factored in the outcome. The thesis follows 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade’s day-to-day struggle through Ortona’s streets to understand how they attempted to impose order on what has historically been labelled as chaos. ii Acknowledgements There were many people that made this thesis possible. First and foremost, I will be eternally grateful to my beautiful wife Courtney Charlotte, who gave me the nudge when she realized that although I was a full time Regular Force career infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment, it was time to follow through with my dream of acquiring a history degree beyond just a Bachelor of Arts. -

Download .Pdf Document

JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 1 what’s who? JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 2 JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 3 New edition, revised and enlarged what’s who? A Dictionary of things named after people and the people they are named after Roger Jones and Mike Ware JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 4 Copyright © 2010 Roger Jones and Mike Ware The moral right of the author has been asserted. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. Matador 5 Weir Road Kibworth Beauchamp Leicester LE8 0LQ, UK Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299 Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277 Email: [email protected] Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador ISBN 978 1848765 214 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 11pt Garamond by Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 5 This book is dedicated to all those who believe, with the authors, that there is no such thing as a useless fact. -

Parachute Battalion Association Newsletter 2 | January 2021 Foreword

151/156 Parachute Battalion Association Newsletter 2 | January 2021 Foreword Dear members, 2020 will long live in our minds with Coronavirus affecting all of us and it continues to be the biggest crisis since World War II. We did, however, manage to hold a successful 79th Reunion Commemoration at Saltby Airfield and at St. Mary’s Church in Melton Mowbray last October, albeit with reduced numbers. We can now look forward to the 80th anniversary of the 151/156 Parachute Battalion this autumn which we are already in the planning stages of and, thanks to our members, already have new material that we will be able to share with you. We have sadly lost our last veteran, Captain Michael Wenner, who passed away on Tuesday, 21st November 2020. He was a brilliant scholar, paratrooper, commando and diplomat but, above all things, he was a compassionate human being. Although a little deaf as many veterans of the 156 were, his gentle nature and warm smile endeared him to all. The following is Michael’s life story which we have been able to put together with the kind help of Raven and Martin Wenner. I think it is such a shame that we have to lose someone before we learn of all their wonderful deeds. Some men excel in one field, some in another, but Michael was one of those rare people who was brilliant in many areas; he was a very special man. Enjoy this Newsletter and keep safe everyone! Rosie Anderson John O’Reilly Will Stark [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 0208 788 0999 01949 851354 01620 481472 2 Captain Michael Alfred Wenner: Paratrooper, Commando and Diplomat 17 March 1921 – 21 November 2020 Airborne Forces Museum Airborne Forces Lieutenant Michael Wenner (circled) whilst serving with the 151 Parachute Battalion in India in October 1942 151/156 Parachute Battalion Association Michael Alfred Wenner died on 21st November 2020. -

Royal Marines Death

ROYAL MARINES DEATH ALEXANDER MACLEAN Private PO/X116565 No. 43 R.M. Commando, Royal Marines, Killed in action on 2nd April 1945 aged 28 Alexander’s parents, Alexander and Dolina (née Mackenzie), both came from Ullapool, but they were married on 15th August 1912 at the Station Hotel, Muir of Ord, Urray Alexander (senior) had been employed as a shepherd in Chile prior to his marriage and the couple sailed to South America soon afterwards. As can be seen below, both Alexander (junior), and his older sister Annie were born overseas, in the Territory of Santa Cruz, Argentine. His father had progressed to the position of manager of a sheep farm, and the family’s residence whilst they were away from Scotland was Hotel Victoria, Punta Arenas, Chile. In 1924 the family set sail for the UK and travelled 1st class on board the ship Romanstar from the River Plate, and disembarked at Liverpool on 15th July. There were now five children: Annie 11, Alexander 9, Kenina 5, Murdo 3 and Maggie 1. Their proposed address was Seaside House, Point Street, Ullapool. 74 Father and mother returned to Chile on board the Oropesa on 9th October that year. They left their three eldest children, Annie, Alexander and Kenina behind in Scotland. Who looked after them? Possibly their grandparents? Father died on 31st December 1932 and is buried in Punta Arenas Municipal Cemetery, Chile. The inscription reads In Loving Memory Of Our beloved Husband and Father ALEXANDER MACLEAN Age 52 Died 31 December 1932 Though out of Sight to memory dear Inserted by his sorrowing widow and family At some stage Dolina and her young family returned to the Ullapool area. -

Canadian War Remembrance and the Ghosts of Ortona

KILLING MATTERS: CANADIAN WAR REMEMBRANCE AND THE GHOSTS OF ORTONA David Ian Cosh A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Social Anthropology York University Toronto, Ontario November 2014 © David Ian Cosh 2014 ii Abstract This dissertation combines critical discourse analysis with person-centred ethnography to examine the dissonant relationships between Canadian war veterans' narratives and the national discourse of Canadian war remembrance. The dissertation analyses Canadian war remembrance as a ritualized discourse (named Remembrance) that is produced in commemorative rituals, symbols, poetry, monuments, pilgrimages, artwork, history-writing, political speeches, government documents, media reports, and the design of the Canadian War Museum. This Remembrance discourse foregrounds and valorizes the suffering of soldiers and makes the soldier's act of dying the central issue of war. In doing so, Remembrance suppresses the significance of the soldier's act of killing and attributes this orientational framework to veterans themselves, as if it is consistent with their experiences. The dissertation problematizes this Remembrance framing of war through an analysis of WWII veterans' narratives drawn from ethnographic fieldwork that was conducted in western Canada with 23 veterans of the WWII battle of Ortona, Italy. The fieldwork consisted of life-story interviews that focused on veterans' combat experiences, supplemented by archival research and a study of the Ortona Christmas reconciliation dinner with former enemy soldiers. Through psychoanalytically-informed discourse analysis, the narratives are interpreted in terms of hidden meanings and trauma signals associated with the issue of killing. -

US Logistical Support of the Allied Mediterranean Campaign, 1942-1945

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public History - Dissertations Affairs 2011 Victory's Foundation: US Logistical Support of the Allied Mediterranean Campaign, 1942-1945 David D. Dworak Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/hst_etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dworak, David D., "Victory's Foundation: US Logistical Support of the Allied Mediterranean Campaign, 1942-1945" (2011). History - Dissertations. 95. https://surface.syr.edu/hst_etd/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in History - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT From November 1942 until May 1945, the Allied nations fought a series of campaigns across the Mediterranean. Ever since, historians have debated the role and impact of the Mediterranean theater upon the greater war in Europe. Through analysis of official archival documents, unit histories from the period, and personal memoirs, this dissertation investigates the impact of US Army service forces on each of the campaigns and operations conducted across the Mediterranean theater. Additionally, this study examines how the campaigns of the Mediterranean shaped and informed the 1944 landings in France and the subsequent drive into Germany. This dissertation argues that the Normandy invasion of 1944 and victory over Germany did not just happen. The success that the Allied forces enjoyed in France and Germany had its foundation set in the learning and experiences of the Mediterranean that began in November 1942. -

“Soldier An' Sailor Too”

“Soldier an' Sailor too ” October 1664 E. J.Sparrow 1 PREFACE On the occasion of the Royal Marines 350 th Birthday perhaps it is worth listing some of their achievements. This booklet takes the form of a day by day diary covering the variety of tasks they have undertaken. A few dates are chosen to show the diversity of the tasks undertaken and the variety of locations where marines have served. Over the course of time they have acquired a remarkable reputation. Their loyalty to the Sovereign is only surpassed by that to their mates. They have fought all over the Globe from Murmansk in the Arctic in 1919 to the Antarctic in more recent years. They fought in desert, jungle and in snow. At sea they have fought in every sort of vessel from battleship to canoe on the surface and also operated below the waves. They have flown in action both fixed wing aircraft and helicopters. They rode into battle on horses and camels plus used reindeer and mules as pack animals. When tragedy strikes be it earthquake, deadly diseases like Ebola, volcano, flooding or fire they have appeared to help with the relief. The Government has used them to cover for striking firemen or control displaced Scottish crofters. The UN has used their services in Peace keeping roles. Several British regiments from the Grenadier Guards to some of the Light Infantry are proud to have served as marines and old enemies like the US and Dutch marines are now the firmest of friends. The Royal Marines have a saying that at the end of their life they cross the harbour bar.