Thesis University of London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratner Kills Mr

Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2008 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN–NORTH BROOKLYN AWP/18 pages • Vol. 31, No. 8/9 • Feb. 23/March 1, 2008 • FREE INCLUDING CARROLL GARDENS, COBBLE HILL, BOERUM HILL, DUMBO, WILLIAMSBURG AND GREENPOINT RATNER KILLS MR. BROOKLYN By Gersh Kuntzman EXCLUSIVE right now,” said Yassky (D– The Brooklyn Paper Brooklyn Heights). “Look, a lot of developers are re-evalut- Developer Bruce Ratner costs had escalated and the num- ing their numbers and feel that has pulled out of a deal with bers showed that we should residential buildings don’t City Tech that could have net not go down that road,” added work right now,” he said. him hundreds of millions of the executive, who did not wish Yassky called Ratner’s dollars and allowed him to to be identified. withdrawal “good news” for build the city’s tallest resi- Costs had indeed escalated. Brooklyn. dential tower, the so-called In 2005, CUNY agreed to pay “A residential building at Mr. Brooklyn, The Brooklyn Ratner $86 million to build the that corner was an awkward Paper has learned. 11- to 14-story classroom-dor- fit,” said Yassky. “A lot of plan- “It was a mutual decision,” mitory and also to hand over ners see that site as ideal for a said a key executive at the City the lucrative development site significant office building.” University of New York, which where City Tech’s Klitgord Forest City Ratner did not would have paid Ratner $300 Auditorium now sits. return two messages from The million to build a new dorm Then in December, CUNY Brooklyn Paper. -

Rock and Roll Rockandrollismyaddiction.Wordpress.Com

The Band, Ten Years After , Keef Hartley Band , Doris Troy, John Lennon ,George Harrison, Leslie West, Grant Green, Eagles, Paul Pena, Bruce Springsteen, Peter Green, Rory Gallagher, Stephen Stills, KGB, Fenton Robinson, Jesse “Ed” Davis, Chicken Shack, Alan Haynes,Stone The Crows, Buffalo Springfield, Jimmy Johnson Band, The Outlaws, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Byrds , Willie Dixon, Free, Herbie Mann, Grateful Dead, Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, Colosseum, Bo Diddley, Taste Iron Butterfly, Buddy Miles, Nirvana, Grand Funk Railroad, Jimi Hendrix, The Allman Brothers, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends Rolling Stones , Pink Floyd, J.J. Cale, Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Humble Pie, Otis Spann Freddie King, Mike Fleetwood Mac, Aretha Bloomfield, Al Kooper Franklin , ZZ Top, Steve Stills, Johnny Cash The Charlie Daniels Band Wilson Pickett, Scorpions Black Sabbath, Iron Butterfly, Buddy Bachman-Turner Overdrive Miles, Nirvana, Son Seals, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton John Mayall, Neil Young Cream, Elliott Murphy, Años Creedence Clearwater Bob Dylan Thin Lizzy Albert King 2 Deep Purple B.B. King Años Blodwyn Pig The Faces De Rock And Roll rockandrollismyaddiction.wordpress.com 1 2012 - 2013 Cuando decidimos dedicar varios meses de nuestras vidas a escribir este segundo libro recopilatorio de más de 100 páginas, en realidad no pensamos que tendríamos que dar las gracias a tantas personas. En primer lugar, es de justicia que agradezcamos a toda la gente que sigue nuestro blog, la paciencia que han tenido con nosotros a lo largo de estos dos años. En segundo lugar, agradecer a todos los que en determinados momentos nos han criticado, ya que de ellas se aprende. Quizás, en ocasiones pecamos de pasión desmedida por un arte al que llaman rock and roll. -

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

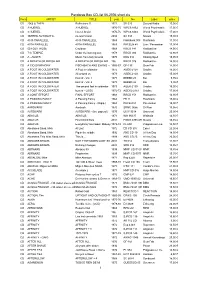

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Wavebid > Buyers Guide

Auction Catalog March 2021 Auction Auction Date: Sunday, Feb 28 2021 Bidding Starts: 12:00 PM EST Granny's Auction House Phone: (727) 572-1567 5175 Ulmerton Rd Email: grannysauction@gmail. Ste B com Clearwater, FL 33760 © 2021 Granny's Auction House 02/28/2021 07:36 AM Lot Title & Description Number 12" x 16" Wyland Lucite Limited Edition Orca Family Statue - Free form clear lucite form reminiscent of ice with sun softened edges 1 holding family pod of 3 Orcas/ killer whales, etched Wyland signature lower left, numbered 105/950 lower right - in house shipping available 2 6" x 4" Russian Lacquerware Box Signed and Numbered with Mythic Cavalry Scene - Black Ground, Bright Red Interior - In House Shipping Available Tiffany & Co. Makers Sterling Silver 6 1/2" plate - 16052 A, 7142, 925-1000, beautiful rimmed plate. 5.095 ozt {in house shipping 3 available} 2 Disney Figurines With Original Boxes & COA - My Little Bambi and Mothe # 14976 & Mushroom Dancer Fantasia. {in house shipping 4 available} 2 Art Glass Paperweights incl. Buccaneers Super Bowl Football - Waterford crystal Super Bowl 37 Buccaneers football #1691/2003 & 5 Murano with copper fleck (both in great condition) {in house shipping available} 6 Hard to Find Victor "His Master's Voice" Neon Sign - AAA Sign Company, Coltsville Ohio (completely working) {local pick up or buyer arranges third party shipping} 7 14K Rose Gold Ring With 11ct Smokey Topaz Cut Stone - size 6 {in house shipping available} 8 5 200-D NGC Millennium Set MS 67 PL Sacagawea Dollar Coins - Slabbed and Graded by NGC, in house shipping available Elsa de Bruycker Oil on Canvas Panting of Pink Cadillac Flying in to the distance - Surrealilst image of cadillac floating above the road 9 in bright retro style, included is folio for Elsa's Freedom For All Statue of Liberty Series - 25" x 23" canvas, framed 29" x 28" local pick up and in house shipping available 10 1887 French Gilt Bronze & Enamel Pendent Hanging Lamp - Signed Emile Jaud Et Jeanne Aubert 17 Mai 1887, electrified. -

New-Musical-Express

WORW'S LARGES! ORCUIA110N OF ANY MUSIC PAPER-WEEKLY IALEI EXCEED 175.000 1MEMBERS OF ABQ ;o-;o. 951 EVERY FRIDAY PRICE 6d. April 9, t965 Regls1trrd :It Ch e G.P.O. IIS o NrH·spapcr A BREATH OF SPRING FROM WALES-THE LAND OF SONG, DAFFODILS AND TOM JONES MIA LEWIS with "WIS& I DIDN'T LOVB RIM" (A LARRY PAGE PRODUCTION) DECCA F.12117 ' ' 1 THANK YOU TO : Personal Management : "About Anglia" Radio London DENMARK PRODUCTIONS LTD. , : Radio Carolin e "Gadzoolcs" cov 3026 "Easybeat" "Discs A Goga" Sole Agency : Radio Lu,cembourg "Roundup" ACUFF-ROSE LTD. "Th ank Your Lucky Stars" MAY 7600 Chrl~ BLACKWELL. .. Chri~ PEERS ... Hany ROBINSON ... ' I\ "'"'enla. BROuB·B1~ JAPMUESMO"!w ,, r'fP R;CDRDS :::E MR.MAILMAN ~R:R::~~R::rel : 'lEGent 8 71 6 . LLT:~DON. w., ~-acsi~i~rs.l RADIO LONDON CLIMBER OF THE WEEK * APPEAR ING OH DISCS A GO GO APRIL 12 SATURDAY CLUI APRIL 17 7 NEW MUSIC.AL EXPRESS Frilluy. April 9, l9fi~ ALL SET FOR SUN DA Y'S GREATEST-EVER POLL WINNERS' CONCERT Cl.LI.A 81..ACK ANI MAIS STOP PRESS More great The stars are all keyed-up! attractions ! SEE NEWS PAGES ISLE OF MAN TV TALENT DISCOVERIES BEAT-JAZZ-FOLK {Group, of four or more members -Folk Group, onl y, throe or more members} PALACE BALLROOM, DOUGLAS 24th to 27t h August, 1 9 6 5 £750 IN PRIZES ,f TOP-PRI ZE TOP GROUP £250 l and 'SWINGI NG-U.K.' T,ophy Competition~ OY""en all ,,;,;1~ mod"un and f-ollf Group music Somi Finals 1 24th & 25rh Augu1t Final , 27th August Special Day Excursion from limpool • \\'rllcnn"· fo r riu1ln1br,, Or,:.unbcr, bk of )fan TV T•l~n l Ubco1 crle1. -

Biffy Clyro the Vertigo of Bliss Mp3, Flac, Wma

Biffy Clyro The Vertigo Of Bliss mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Vertigo Of Bliss Country: UK Released: 2003 Style: Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1579 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1789 mb WMA version RAR size: 1900 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 568 Other Formats: MP3 MMF AC3 AA AAC AIFF ADX Tracklist 1 Bodies In Flight 5:17 2 The Ideal Height 3:41 3 With Aplomp 5:29 4 A Day Of... 2:24 5 Liberate The Illiterate 5:28 6 Diary Of Always 4:04 7 Questions & Answers 4:02 8 Eradicate The Doubt 4:26 9 When The Faction's Fractioned 3:36 10 Toys, Toys, Toys, Choke, Toys, Toys, Toys 5:28 11 All The Way Down... 6:43 12 A Man Of His Appalling Posture 3:25 13 Now The Action Is On Fire! 5:53 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Biffy The Vertigo Of BBQLP 233 Beggars Banquet BBQLP 233 UK 2003 Clyro Bliss (LP, Album) Beggars Banquet, Biffy The Vertigo Of Hostess BGJ-10128 BGJ-10128 Japan 2004 Clyro Bliss (CD, Album) Entertainment Unlimited none, Biffy The Vertigo Of Beggars Banquet, none, Japan 2004 KICP-986 Clyro Bliss (CD, Album) King Record Co. Ltd KICP-986 The Vertigo Of none, Biffy Beggars Banquet, none, Bliss (CD, Album, Japan 2004 DCH-15034 Clyro King Record Co. Ltd DCH-15034 Promo) The Vertigo Of Biffy Bliss (2xLP, BBQLP 2090 Beggars Banquet BBQLP 2090 UK 2013 Clyro Album, Ltd, RE, Whi) Related Music albums to The Vertigo Of Bliss by Biffy Clyro 1. -

First Steps with the Drum Set a Play Along Approach to Learning the Drums

First Steps With The Drum Set a play along approach to learning the drums JOHN SAYRE www.JohnSayreMusic.com 1 CONTENTS Page 5: Part 1, FIRST STEPS Money Beat, Four on the Floor, Four Rudiments Page 13: Part 2, 8th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 18: Part 3, ROCK GROOVES 8th notes, Queen, R.E.M., Stevie Wonder, Nirvana, etc. Page 22: Part 4, 16th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 27: Part 5, 16th NOTES ON DRUM SET Page 34: Part 6, PLAYING IN BETWEEN THE HI-HAT David Bowie, Bob Marley, James Brown, Led Zeppelin etc. Page 40: Part 7, RUDIMENTS ON THE DRUM SET Page 46: Part 8, 16th NOTE GROOVES Michael Jackson, Erykah Badu, Imagine Dragons etc. Page 57: Part 9, TRIPLETS Rudiments, Accents Page 66: Part 10, TRIPLET-BASED GROOVES Journey, Taj Mahal, Toto etc. Page 72: Part 11, UNIQUE GROOVES Grateful Dead, Phish, The Beatles etc. Page 76: Part 12, DRUMMERS TO KNOW 2 INTRODUCTION This book focuses on helping you get started playing music that has a backbeat; rock, pop, country, soul, funk, etc. If you are new to the drums I recommend working with a teacher who has a healthy amount of real world professional experience. To get the most out of this book you will need: -Drumsticks -Access to the internet -Device to play music -Good set of headphones—I like the isolation headphones made by Vic Firth -Metronome you can plug headphones into -Music stand -Basic understanding of reading rhythms—quarter, eighth, triplets, and sixteenth notes -Drum set: bass drum, snare drum, hi-hat is a great start -Other musicians to play with Look up any names, bands, and words you do not know. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

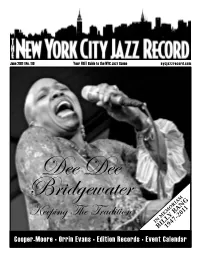

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999) Interviewee: Art Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown Dates: June 29-30, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 96 pp. Brown: Today is June 29, 1995. This is the Jazz Oral History Program interview for the Smithsonian Institution with Art Farmer in one of his homes, at least his New York based apartment, conducted by Anthony Brown. Mr. Farmer, if I can call you Art, would you please state your full name? Farmer: My full name is Arthur Stewart Farmer. Brown: And your date and place of birth? Farmer: The date of birth is August 21, 1928, and I was born in a town called Council Bluffs, Iowa. Brown: What is that near? Farmer: It across the Mississippi River from Omaha. It’s like a suburb of Omaha. Brown: Do you know the circumstances that brought your family there? Farmer: No idea. In fact, when my brother and I were four years old, we moved Arizona. Brown: Could you talk about Addison please? Farmer: Addison, yes well, we were twin brothers. I was born one hour in front of him, and he was larger than me, a bit. And we were very close. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: So, you were fraternal twins? As opposed to identical twins? Farmer: Yes. Right.