Iran and Israel's Undeclared War at Sea (Part 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undeclared War: Unmanned Drones, Human Rights and Collective Security

Undeclared War: unmanned drones, human rights and collective security Susan Carolyn Breau, University of Reading/Mark Olssen, University of Surrey Drones constitute, as Barbara Ehrenreich notes, in her ‘Foreword’ to Medea Benjamin’s Drone Warfare: Killing by remote control, the “ultimate action-at-a-distance weapons, allowing the aggressor to destroy targets in Pakistan or Afghanistan while ‘hiding’ thousands of miles away in Nevada” (Ehrenreich, 2013, p. vii). Yet, as Ehrenreich continues, “it is hard to even claim that their primary use is ‘military’ in any traditional sense. Drones have made possible a programme of targeted assassinations that are justified by the US ‘war on terror’, but otherwise in defiance of both international and US law” (p. viii). She notes how Benjamin in her book documents impressively how “it is the CIA, not the Pentagon, that operates most drone strikes in Western Asia, with no accountability whatsoever. Designed targets…have been condemned without evidence or trial – at the will apparently, of the White House. And those who operate the drones do so with complete impunity for the deaths of any civilians who end up as collateral damage.” (p. viii) Although the technical expertise for producing drones was developed as early as the WWI, and although unmanned aerial vehicles were used for gathering intelligence and for reconnaissance during WWII and during the Vietnam and later Balkan wars, their adaptation to becoming lethal military vehicles for the purposes of attacking and destroying specified targets has taken place more recently. Although Abraham Karem assisted the Israeli’s in developing unmanned robots in the 1970s, and built the first Predator drone in his garage in Southern California in the early 1980s 1, the first official use in military conflict only occurred since 1999 with the NATO Kosovo intervention where unmanned robotic aircraft were adapted to carry missiles “transforming them from spy planes into killer drones” (Benjamin, p. -

Civilians in Cyberwarfare: Conscripts

Civilians in Cyberwarfare: Conscripts Susan W. Brenner* with Leo L. Clarke** ABSTRACT Civilian-owned and -operated entities will almost certainly be a target in cyberwarfare because cyberattackers are likely to be more focused on undermining the viability of the targeted state than on invading its territory. Cyberattackers will probably target military computer systems, at least to some extent, but in a departure from traditional warfare, they will also target companies that operate aspects of the victim nation’s infrastructure. Cyberwarfare, in other words, will penetrate the territorial borders of the attacked state and target high-value civilian businesses. Nation-states will therefore need to integrate the civilian employees of these (and perhaps other) companies into their cyberwarfare response structures if a state is to be able to respond effectively to cyberattacks. While many companies may voluntarily elect to participate in such an effort, others may decline to do so, which creates a need, in effect, to conscript companies for this purpose. This Article explores how the U.S. government can go about compelling civilian cooperation in cyberwarfare without violating constitutional guarantees and limitations on the power of the Legislature and the Executive. * NCR Distinguished Professor of Law and Technology, University of Dayton School of Law. ** Associate, Drew, Cooper & Anding, P.C., Grand Rapids, Michigan. 1011 1012 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law [Vol. 43:1011 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................. -

America's Undeclared Naval War

America's Undeclared Naval War Between September 1939 and December 1941, the United States moved from neutral to active belligerent in an undeclared naval war against Nazi Germany. During those early years the British could well have lost the Battle of the Atlantic. The undeclared war was the difference that kept Britain in the war and gave the United States time to prepare for total war. With America’s isolationism, disillusionment from its World War I experience, pacifism, and tradition of avoiding European problems, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved cautiously to aid Britain. Historian C.L. Sulzberger wrote that the undeclared war “came about in degrees.” For Roosevelt, it was more than a policy. It was a conviction to halt an evil and a threat to civilization. As commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces, Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy from neutrality to undeclared war. It was a slow process as Roosevelt walked a tightrope between public opinion, the Constitution, and a declaration of war. By the fall of 1941, the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy were operating together as wartime naval partners. So close were their operations that as early as autumn 1939, the British 1 | P a g e Ambassador to the United States, Lord Lothian, termed it a “present unwritten and unnamed naval alliance.” The United States Navy called it an “informal arrangement.” Regardless of what America’s actions were called, the fact is the power of the United States influenced the course of the Atlantic war in 1941. The undeclared war was most intense between September and December 1941, but its origins reached back more than two years and sprang from the mind of one man and one man only—Franklin Roosevelt. -

The Massachusetts Antiwar Bill, by Anthony A

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 1970 The aM ssachusetts Antiwar Bill Anthony D'Amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation D'Amato, Anthony, "The asM sachusetts Antiwar Bill" (1970). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 126. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/126 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. The Massachusetts Antiwar Bill, by Anthony A. D'Amato,* 42 New York State Bar Journal 639-649 (1970) Abstract: The Massachusetts Antiwar bill provides that no inhabitant of Massachusetts inducted into or serving in the armed forces “shall be required to serve” abroad in an armed hostility that has not been declared a war by Congress under Art. I, Sect. 8 of the United States Constitution. One could hardly imagine a more fundamental constitutional doubt arising in the mind of the American public than that of the legality of a major war. The purpose of the Massachusetts bill is purely and simply to obtain an authoritative judicial test of the constitutionality of an undeclared war. Tags: Massachusetts Antiwar Bill, Vietnam War, Massachusetts v. Laird, U.S. Constitution Article I Section 8, Prize Cases, Standing [pg639]** One of the most singular pieces of legislation in American constitutional history passed both houses of the Massachusetts legislature on April 1st, 1970, and was signed into law, effective immediately, on the following day by Governor Francis W. -

Law of War Handbook 2005

LAW OF WAR HANDBOOK (2005) MAJ Keith E. Puls Editor 'Contributing Authors Maj Derek Grimes, USAF Lt Col Thomas Hamilton, USMC MAJ Eric Jensen LCDR William O'Brien, USN MAJ Keith Puls NIAJ Randolph Swansiger LTC Daria Wollschlaeger All of the faculty who have served before us and contributed to the literature in the field of operational law. Technical Support CDR Brian J. Bill, USN Ms. Janice D. Prince, Secretary JA 423 International and Operational Law Department The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School Charlottesville, Virginia 22903 PREFACE The Law of War Handbook should be a start point for Judge Advocates looking for information on the Law of War. It is the second volume of a three volume set and is to be used in conjunction with the Operational Law Handbook (JA422) and the Documentary Supplement (JA424). The Operational Law Handbook covers the myriad of non-Law of War issues a deployed Judge Advocate may face and the Documentary Supplement reproduces many of the primary source documents referred to in either of the other two volumes. The Law of War Handbook is not a substitute for official references. Like operational law itself, the Handbook is a focused collection of diverse legal and practical information. The handbook is not intended to provide "the school solution" to a particular problem, but to help Judge Advocates recognize, analyze, and resolve the problems they will encounter when dealing with the Law of War. The Handbook was designed and written for the Judge Advocates practicing the Law of War. This body of law is known by several names including the Law of War, the Law of Armed Conflict and International Humanitarian Law. -

Name: 00001205

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/38/651 8 December 1983 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH 'OA/ Thirty-eighth session Agenda item 29 THE SITUATION IN AFGHANISTAN AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE AND SECURITY Letter dated 7 December 1983 from the Permanent Representative of Afghanistan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the General Assembly I have the honour to refer to my statement of 23 November 1983 1/ in exercise of the right of reply of my delegation, in the course of which I requested Your Excellency to issue as a document of the General Assembly the full text of my statement which I could not conclude owing to the shortage of time. I have further the honour to submit to you the full text of that statement with the request for its distribution as a document of the General Assembly under agenda item 29. (Signed) M. Farid ZARIF Ambassador Permanent Representative 1/ A/38/PV.69, p. 52. 83-34878 1056u (E) /.. A/38/651 English ANNEX Page 2 Statement by the Permanent Representative of Afghanistan In his statement yesterday in this Assembly, the Head of the Pakistan delegation referred to my Government as a regime which was installed and is being sustained by alien forces. His falacious version of the reality, notwithstanding, we regret the fact that not all delegations abide by the elementary rules of ethics in this Assembly or in their inter-state relations. "Te therefore abstain from calling his government as the Islamabad military regime which is being sustained by bayonets and bullets. -

The Changkufeng and Nomonhan Incidents – the Undeclared Border War and Its Impact on World War Ii

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2014-01-01 The hC angkufeng And Nomonhan Incidents - The Undeclared Border War And Its Impact on World War II Tobias Block University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Block, Tobias, "The hC angkufeng And Nomonhan Incidents - The ndeU clared Border War And Its Impact on World War II" (2014). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1588. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1588 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGKUFENG AND NOMONHAN INCIDENTS – THE UNDECLARED BORDER WAR AND ITS IMPACT ON WORLD WAR II TOBIAS BLOCK DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APPROVED: __________________________________________ Joshua Fan, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________________ Paul Edison, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Jose Villalobos, Ph.D. __________________________________ Bess Sirmon-Taylor, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School THE CHANGKUFENG AND NOMONHAN INCIDENTS - THE UNDECLARED BORDER WAR AND ITS IMPACT ON WORLD WAR II by Tobias Block, BA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department Of HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS OF EL PASO May 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Cyber War and Terrorism: Towards a Common Language to Promote Insurability

Cyber War and Terrorism: Towards a common language to promote insurability July 2020 Cyber War and Terrorism: Towards a common language to promote insurability Rachel Anne Carter, Director Cyber, The Geneva Association Julian Enoizi, CEO, Pool Reinsurance Company Limited, and Secretariat, International Forum of Terrorism Risk (Re)Insurance Pools Cyber War and Terrorism: Towards a common language to promote insurability 1 The Geneva Association The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and societies, and thus a more sustainable world. International Forum of Terrorism Risk (Re)Insurance Pools The International Forum of Terrorism Risk (Re)Insurance Pools (IFTRIP) is a collaboration between global terrorism (re)insurance pools. It was formally ratified at the National Terrorism Reinsurance Pools Congress organised by the Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation (ARPC) in Canberra in October 2016. The organisation was founded with the goal of promoting initiatives for closer international collaboration and sharing expertise and experience to combat the threat of potential major economic loss resulting from terrorism. -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy. -

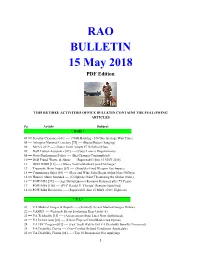

Bulletin 180515 (PDF Edition)

RAO BULLETIN 15 May 2018 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 04 == Security Clearances [01] ---- (740K Backlog - 540 Day Average Wait Time) 05 == Arlington National Cemetery [75] ---- (Burial Rules Changing) 06 == NDAA 2019 ---- (House Panel Adopts $716 Billion Plan) 07 == DoD Tuition Assistance [07] ---- (Corps Lowers Requirements) 08 == Navy Deployment Policy ---- (Big Changes Contemplated) 10 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 MAY 2018) 11 == DOD PDBR [13] ---- (Where You Lowballed Upon Discharge? 13 == Traumatic Brain Injury [67] ---- (Shoulder-Fired Weapon Use Impact) 14 == Commissary Sales [04] ---- (Beer and Wine Sales Begin within Next 90 Days) 14 == Huawei Alarm Sounded ---- (Cellphone Giant Threatening the Global Order) 16 == POW/MIA [99] ---- (Sgt. David Quinn’s Remains Returned after 75 Years) 17 == POW/MIA [100] ---- (PFC Harold V. Thomas’ Remains Identified) 18 == POW/MIA Recoveries ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 MAY 2018 | Eighteen) . * VA * . 21 == VA Medical Images & Reports ---- (Securely Access Medical Images Online) 22 == VASRD ---- (Vision & Breast Evaluation Regs Updated) 23 == VA Telehealth [15] ---- (Access across State Lines Now Authorized) 23 == VA Debit Cards [01] ---- (Direct Express Debit Mastercard Option) 24 == VA FDC Program [03] ---- (Fast Track Way to Get VA Disability Benefits Processed) 25 == VA Disability Claims ---- (Non-Combat Related Conditions Applicable) 25 == VA Disability Claims [01] ---- (Top 10 Reasons -

Law of War Deskbook, 2011

LAW OF WAR DESKBOOK INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT The United States Army Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School Charlottesville, VA 2011 International Law Private Law Public Law (conflict of laws, commercial) (intergovernmental) Law of War Law of Peace Conflict Management Rules of Hostilities Jus ad Bellum Jus in Bello U.N. Charter Hague Conventions Arms Control Geneva Conventions Customary Law Customary Law INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL‘S LEGAL CENTER AND SCHOOL, U.S. ARMY CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA LAW OF WAR DESKBOOK Authors LTC Jeff A. Bovarnick, JA, USA LtCol(Sel.) J. Jeremy Marsh, USAF MAJ Gregory S. Musselman, JA, USA LCDR John B. Reese, JA, USN MAJ Shane R. Reeves, JA, USA MAJ Robert E. Barnsby, JA, USA MAJ Sean M. Condron, JA, USA Maj Andrew D. Gillman, JA, USAF Capt Iain Pedden, JA, USMC All of the faculty who have served with and before us and contributed to the literature in the field of the Law of War Editor MAJ Gregory S. Musselman Technical Support Ms. Terri Thorne Mr. Gabriel Park 2011 PREFACE This Law of War Deskbook is intended to replace, in a single bound volume, similar individual outlines that had been distributed as part of the Judge Advocate Officer Graduate and Basic Courses and the Operational Law of War Course. Together with the Operational Law Handbook and Law of War Documentary Supplement, these three volumes represent the range of international and operational law subjects taught to military judge advocates. These outlines, while extensive, make no pretence of comprehensively covering this complex area of law. -

Jeffersonianism and 19Th Century American Maritime Defense Policy. Christopher Taylor Ziegler East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2003 Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy. Christopher Taylor Ziegler East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ziegler, Christopher Taylor, "Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy." (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 840. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/840 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History By Christopher T. Ziegler December 2003 Dale Royalty Ronnie Day Dale Schmitt Keywords: Thomas Jefferson, Jeffersonianism, Maritime Defense, Navy, Coastal Defense, Embargo, Non-importation ABSTRACT Jeffersonianism and 19th Century American Maritime Defense Policy By Christopher T. Ziegler This paper analyzes the fundamental maritime defense mentality that permeated America throughout the early part of the Republic. For fear of economic debt and foreign wars, Thomas Jefferson and his Republican party opposed the construction of a formidable blue water naval force. Instead, they argued for a small naval force capable of engaging the Barbary pirates and other small similar forces.