Investigating Paper Ticket Usage on London Underground's Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

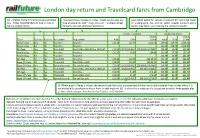

London Day Return and Travelcard Fares from Cambridge

London day return and Travelcard fares from Cambridge GA = Greater Anglia for trains to Liverpool Street Time restrictions Monday to Friday. Tickets can be used any Fares listed below for London Travelcard (for unlimited travel Any = Either Great Northern to King’s Cross or time at weekends. KGX = King’s Cross LST = Liverpool Street on underground, bus and rail within Greater London) and a GA to Liverpool Street Railcards may add additional restrictions London Day Return just covering the rail fare to London. London Travelcard London Day Return 2 Adult 2 Adult Ticket Operator Railcard Arr London Dep London Adult Child 2 Child Adult Child 2 Child Anytime Day Any No Any time Any time £47.50 £23.75 £142.50 £39.50 £19.75 £118.50 Anytime Day GA No Any time Any time £36.00 £18.00 £108.00 Off-Peak Any No After 1000 Not 1628 to 1901 KGX or 1835 LST £31.50 £15.75/£2.00[1] £78.15[G]/£67.00[1] £24.00 £2.00 £52.00 Anytime Day Any Yes Any time Any time £31.35 £9.05 £80.80 £26.05 £7.50 £67.10 Anytime Day GA Yes Any time Any time £23.75 £6.85 £61.20 Off-Peak GA No After 1000 Any time £25.40 £12.70 £62.95[G] £21.10 £2.00 £46.20 Super Off-Peak GA No After 1200 Not 1558 to 1902 £24.00 £12.00 £59.55[G] £16.40 £2.00 £36.80 Super Off-Peak Any No Sat and Sun only Sat and Sun only £22.50 £11.25/£2.00[1] £55.80[G]/£49.00[1] £16.50 £2.00 £37.00 Off-Peak Any Yes After 1000 Not 1628 to 1901 KGX or 1835 LST £20.80 £6.00/£2.00[1] £53.60/£45.60[1] £15.85 £2.00 £35.70 Off-Peak GA Yes After 1000 Any time £16.75 £4.85 £43.20 £13.95 £2.00 £31.90 Super Off-Peak GA Yes -

Oyster Conditions of Use on National Rail Services

Conditions of Use on National Rail services 1 October 2015 until further notice 1. Introduction 1.1. These conditions of use (“Conditions of Use”) set out your rights and obligations when using an Oyster card to travel on National Rail services. They apply in addition to the conditions set out in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, which you can view and download from the National Rail website nationalrail.co.uk/nrcoc. Where these Conditions of Use differ from the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, these Conditions of Use take precedence when you are using your Oyster card. 1.2 When travelling on National Rail services, you will also have to comply with the Railway Byelaws. You can a get free copy of these at most staffed National Rail stations, or download a copy from the Department for Transport website dft.gov.uk. 1.3 All Train Companies operating services into the London Fare Zones Area accept valid Travelcards issued on Oyster cards, except Heathrow Express and Southeastern High Speed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International. In addition, the following Train Companies accept pay as you go on Oyster cards for travel on their services within the London National Rail Pay As You Go Area. Abellio Greater Anglia Limited (trading as Greater Anglia) The Chiltern Railway Company Limited (trading as Chiltern Railways) First Greater Western Limited (trading as Great Western Railway) (including Heathrow Connect services between London Paddington and Hayes & Harlington) GoVia Thameslink Railway Limited (trading as Great Northern, as Southern and as Thameslink) London & Birmingham Railway Limited (trading as London Midland) London & South Eastern Railway Company (trading as Southeastern) (Special fares apply on Southeaster highspeed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International). -

Making Rail Accessible: Helping Older and Disabled Customers

TfL Rail Making rail accessible: Helping older and disabled customers May 2016 MAYOR OF LONDON Contents Our commitment to you page 3 Commitments page 5 Assistance for passengers page 6 Alternative accessible transport page 9 Passenger information page 10 Fares and tickets page 12 At the station page 16 On the train page 17 Making connections page 19 Accessible onward transport page 20 Disruption to facilities and services page 21 Contact us page 23 Station accessibility information page 24 Contact information back page 2 Our commitment to you TfL Rail is managed by Transport for London (TfL) and operated by MTR Crossrail. We operate rail services between Liverpool Street and Shenfield. At TfL Rail, we are committed to providing you with a safe, reliable and friendly service. We want to make sure that you can use our services safely and in comfort. 3 Our commitment to you (continued) We recognise that our passengers may have different requirements when they travel with us and we are committed to making your journey as easy as possible. This applies not only to wheelchair users, but also: • Passengers with visual or auditory impairment or learning disabilities • Passengers whose mobility is impaired through arthritis or other temporary or long term conditions • Older people • Passengers accompanying disabled children in pushchairs • Disabled passengers requiring assistance with luggage We welcome your feedback on the service we provide and any suggestions you may have for improvements. Our contact details are shown on the back page of this -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Proposals to Manage the Demand for Travel

255 Proposals to manage the demand for travel 5.24 Better journey planning Proposal 115 and smarter travel for people The Mayor, through TfL, and working and goods with the London boroughs, DfT, Network Rail, train operating companies, and other 5.24.1 Public transport and road stakeholders, will enhance the provision user information of information to improve customers’ knowledge and understanding of service 626 Good quality information will improve availability, delays and other information to Chapter five passenger flow, with associated wellbeing improve customer satisfaction, and the way benefits of convenience and ease which can Londoners use public transport and make improve the journey experience, especially if travel decisions, by: disruptions occur Current satisfaction for road a) Improving the provision of real traffic information is less than 60 per cent, time and other journey planning so there is clearly more to do For public information, including upgrading the transport, customer satisfaction on information TfL web-based journey planner, allowing is rising There is the opportunity to build further improvements to its real time on TfL’s extensive work in this area, such as performance, accuracy and personalisation its award-winning website, Journey Planner and iBus, by allowing wider access to service b) Providing customers with a range of information anywhere in London using mobile paper-based information (Tube, cycle phone and internet technology, resulting in and bus ‘spider’ maps, timetables, fares better journey planning -

C2c Rail Limited's Accessible Travel Policy Approval Decision Letter And

Marcus Clements Head of Consumer Policy Rail Markets and Economics Email: 08 March 2021 Julian Drury Managing Director c2c By Email Dear Julian, Approval of Trenitalia c2c Limited’s (c2c’s) Accessible Travel Policy (Condition 5 of the Station Licence and GB Statement of National Regulatory Conditions: Passenger) Thank you for submitting c2c’s revised Accessible Travel Policy (ATP) for approval. We have reviewed the ATP against the September 2020 “Accessible Travel Policy Guidance for Train and Station Operators” (the guidance). I can confirm that c2c’s ATP now meets the requirements of Condition 5 of its station licence and GB Statement of National Regulatory Conditions: Passenger (SNRP). When I last wrote to you on 27 August 2020, confirming the approval of your previous ATP, I asked for further details of c2c’s disability awareness training package, and updates on progress towards meeting WCAG standards for website accessibility. This information has now been provided. I shall be grateful for ongoing updates on these two issues during the ATP Quarterly meetings we plan to hold throughout 2021. I also referred to the provision of assistance at stations where ticket office hours were reduced. We will continue to keep the provision of unbooked assistance under review to ensure that, when passenger numbers increase, waiting times remain within reasonable parameters. Please provide a branded version of all ATP documents by 5 April 2021. A copy of the approved ATP will then be published on our website along with a copy of this letter. As you are aware, ATPs must be reviewed by operators on an annual basis. -

Your Staff Guide to Fares and Ticketing

Staff Guide to Fares and Ticketing From 2nd January 2017 Book 1: Fares and tickets Fares and tickets Fares and tickets The Staff Guide to Fares and Tickets is divided into three separate booklets plus Appendices: Book 1: Fares and tickets. This booklet: • summarises the range of ticket types and ticket media that are accepted on TfL and National Rail services in London • details fares and ticket prices for all services, split down by main passenger types • ONLY INCLUDES A GENERAL GUIDE TO SINGLE FARES ON TfL’s RAIL SERVICES IN ZONES 1-9. Please use single fare finder to check the fare between any two named stations Book 2: Types of tickets, ways to pay and how to use Oyster and contactless payment cards Book 3: Discounts and concessions Appendices: includes maps and tables of where to buy each ticket type What has changed since September 2016? • The following fares are frozen until 2020 o All fares on buses and trams o All single pay as you go fares and paper single tickets on Tube and DLR services o Most single pay as you go fares and paper single tickets on London Overground and TfL Rail services • Pay as you go fares set by Train Operating Companies will change, including: o TfL/NR through fares o journeys on former Greater Anglia London Overground routes and TfL Rail, between: – Liverpool Street and Cheshunt (and intermediate stations) – Shenfield and Zone 2 or Zone 3 Fares and tickets • Cash single fares set by Train Operating Companies will increase: o TfL/NR through fares o most TfL Rail o most London Overground journeys on the former Greater Anglia routes and from Shadwell southwards • Rail/all modes caps have changed • Travelcard prices have changed o Zones 2-9 and Zones 4-9 will be withdrawn. -

Background Information for the Transport Committee's Meeting on 7 March on Crossrail and the Future for Rail in London

Background information for the Transport Committee’s meeting on 7 March on Crossrail and the future for rail in London This document contains written submissions received for the Transport Committee’s review of Crossrail and the future for rail in London. Contents: Page number: Submissions received from stakeholders: 1. Crossrail 1 2. Network Rail 23 3. Travelwatch 28 4. ORR 35 5. RailFreight 37 6. TfL response to NR business plan 39 Submissions received from rail user groups and members of the public: 7. London Forum of Civic & Amenity Societies 47 8. Brent Council 49 9. Graham Larkbey 50 10. Clapham Transport User Group Submission 50 11. Simon Fisher 62 12. West London Line Group 64 13. James Ayles 67 12. East Surrey Transport Committee 69 Report for the London Assembly Transport Committee Document Number: CR-XRL-Z-RGN-CR001-50004 Document History: Version: Date: Prepared by: Checked by: Authorised by: Reason for Revision: For issue to the London Andrew 1.0 27-02-13 Luke Jouanides Sarah Johnson Assembly Transport Wolstenholme Committee This document contains proprietary information. No part of this document may be reproduced without prior written consent from the chief executive of Crossrail Ltd. Page 1 of 22 © Crossrail Limited 1 Document Title Document Number CR-XRL-Z-RGN-CR001-50004 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 2 Delivery: progress, scope, risk and schedule ........................................................ 3 2.1 Progress -

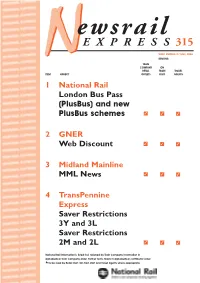

E X P R E S S

337624_Newsletter_315 12/5/06 1:30 pm Page 1 ewsrail EXPRESS315 WEEK ENDING 27 May 2006 ITEM FOR TRAIN NN COMPANY ON RETAIL TRAIN TRAVEL ITEM SUBJECT OUTLETS STAFF AGENTS 1 National Rail London Bus Pass (PlusBus) and new PlusBus schemes ✓ ✓ ✓ 2 GNER Web Discount ✓ ✓ ✓ 3 Midland Mainline MML News ✓ ✓ ✓ 4TransPennine Express Saver Restrictions 3Y and 3L Saver Restrictions 2M and 2L ✓ ✓ ✓ National Rail information is listed first, followed by Train Company information in alphabetical Train Company order. Further items follow in alphabetical contributor order. *To be read by Retail Staff, On-Train Staff and Travel Agents where appropriate. 337624_Newsletter_315 12/5/06 1:30 pm Page 2 ADDITIONAL PUBLICATIONS The list shows additional publications included with this Newsrail Express. If you do not receive them, or need extra copies, rail staff should see ‘Further Supplies’. Travel Agents please contact your Sales Office. 1. ITEMS YOU SHOULD HAVE RECEIVED PUBLICATION NAME SENT NEWSRAIL TO EXPRESS NUMBER None 2. CONTACTS FOR FURTHER SUPPLIES – FOR RAIL STAFF Customer Services TSO St. Crispins Duke Street Norwich NR3 1PD Tel: 0870 850 2149 Fax: 0870 600 5533 3. DISTRIBUTION DATABASE – FOR RAIL STAFF You should advise any publications database amendments to your Retail Manager, Pricing Manager or to Customer Services, TSO, St. Crispins, Duke Street, Norwich NR3 1PD Tel: 0870 850 2149, Fax: 0870 600 5533, E-mail: [email protected] 2 337624_Newsletter_315 12/5/06 1:30 pm Page 3 TO BE READ BY: TRAIN COMPANY RETAIL STAFF ✓ ON-TRAIN STAFF ✓ 1 TRAVEL AGENTS ✓ London Bus Pass (PlusBus) and new PlusBus schemes PlusBus is a combined train and bus ticket giving unlimited bus travel for one day and Season Tickets (where available) within pre-set zones around participating National Rail stations. -

Oyster Conditions Of

Conditions of Use on National Rail services 1 October 2015 until further notice 1. Introduction 1.1. These conditions of use (“Conditions of Use”) set out your rights and obligations when using an Oyster card to travel on National Rail services. They apply in addition to the conditions set out in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, which you can view and download from the National Rail website nationalrail.co.uk/nrcoc. Where these Conditions of Use differ from the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, these Conditions of Use take precedence when you are using your Oyster card. 1.2 When travelling on National Rail services, you will also have to comply with the Railway Byelaws. You can a get free copy of these at most staffed National Rail stations, or download a copy from the Department for Transport website dft.gov.uk. 1.3 All Train Companies operating services into the London Fare Zones Area accept valid Travelcards issued on Oyster cards, except Heathrow Express and Southeastern High Speed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International. In addition, the following Train Companies accept pay as you go on Oyster cards for travel on their services within the London National Rail Pay As You Go Area. Abellio Greater Anglia Limited (trading as Greater Anglia) The Chiltern Railway Company Limited (trading as Chiltern Railways) First Greater Western Limited (trading as Great Western Railway) (including Heathrow Connect services between London Paddington and Hayes & Harlington) GoVia Thameslink Railway Limited (trading as Great Northern, as Southern and as Thameslink) London & Birmingham Railway Limited (trading as London Midland) London & South Eastern Railway Company (trading as Southeastern) (Special fares apply on Southeaster highspeed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International). -

Ways to Pay on Buses

Ways to pay on buses January 2018 There are many ways to pay on London’s buses and we accept various tickets and passes. We don’t take cash but we have several options for you to pay the cheapest fare. On some routes, other special ticket arrangements may apply. If you need assistance with fares and tickets on London Buses, visit our website tfl.gov.uk/fares or contact us on 0343 222 1234 (24 hours). On all routes Printed tickets The following printed tickets can be used on all buses and bought at Tube and rail stations: Day Travelcards* Day Bus & Tram passes 7 Day, Monthly and Annual Travelcard season tickets* *Tickets issues by train operators must show TfL’s logo and/or ‘Travelcard’ to be valid on buses Oyster and contactless payments You can pay as you go on all our buses with Oyster and contactless. All journeys cost £1.50 with a daily price cap of £4.50. You can also buy Bus & Tram passes for your Oyster card. Children aged between 11 and 16 can The Hopper fare allows unlimited bus get free bus and tram travel with a and tram journeys for the price of one Zip card. For more information and within 60 minutes. Make sure you use to apply for a card visit tfl.gov.uk/zip . the same card for each journey. We accept the following contactless cards* and methods of payment: Apple Pay EE Cash on Tap Android Pay Samsung Pay bPay from Barclaycard Vodafone Pay (including PayPal) Barclays Contactless Mobile *UK cards and some international cards accepted. -

Review of Tfl Rail DPPP

Annette Egginton Head of Competition and Consumer Policy Directorate of Railway Markets & Economics Email: [email protected] 24 October 2016 Steve Murphy Managing Director MTR Crossrail Dear Steve, Review of MTR Crossrail (trading as TfL Rail) Disabled People’s Protection Policy (Condition 5 of your Station Licence and GB Passenger Statement of National Regulatory Conditions) Thank you for providing updated versions of your Disabled People’s Protection Policy (DPPP) documents for review. A copy of your revised DPPP is attached to this letter, and will be published on our website along with a copy of this letter. I confirm that we have reviewed your DPPP against the 2009 Guidance “How to write your Disabled People’s Protection Policy: A guide for Train and Station Operators” (the guidance) and can confirm that your revised DPPP meets the requirements of Condition 5 of your station licence and GB Passenger Statement of National Regulatory Conditions (SNRP). We welcome your commitments to the following: ‘Turn Up and Go’ policy which means that customers can turn up at any TfL Rail station without pre-booking and staff will provide assistance, including assistance with luggage. Since your DPPP was originally submitted to ORR we have had some exchanges in the intervening period in order to bring about the changes required to make it fully compliant with the Guidance. The main area where you clarified your policy during our review was regarding Passenger Assist. In recognition of the fact that you manage both trains and stations you are required to participate in Passenger Assist.