The Niger Delta: 'Petro Violence'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

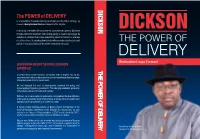

The POWER of DELIVERY Is a Compilation of Selected Extempore Remarks, and the first of a Trilogy, by Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State, Nigeria

DICKS The POWER of DELIVERY is a compilation of selected extempore remarks, and the first of a trilogy, by Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. ON In this book, the reader will encounter the robustness of Governor Dickson's DICKSON remarks delivered extempore with striking ability to inspire and engage its audience in a manner that is most compelling. Governor Dickson is an orator of a different hue. He speaks authoritatively with penetrating intellectual depth THE POWER OF typical of most great leaders in the world, both past and present. DELIVERY Restoration Leaps Forward GOVERNOR HENRY SERIAKE DICKSON A PROFILE THE POWER OF DELIVERY Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State in Nigeria has, by his performance in office, underscored the critical role of leadership in strategic restructuring and effective governance. He has changed the face of development, sanitized the polity, and encouraged participatory governance. The emerging economic prosperity in Bayelsa is a product of vision and courage. Dickson, 48, is an exceptional leader whose foresight on the diversification of the state’s economy beyond oil and gas to focus more on tourism and agriculture holds great promise of economic boom. A lawyer, former Attorney-General of Bayelsa State and member of the National Executive Committee of the Nigerian Bar Association, he was elected to the House of Representatives in 2007 and re-elected in 2011, where he served as the Chairman, House Committee on Justice. His star was further on the rise when he was elected governor of Bayelsa State by popular acclamation later in 2012. He has been an agent of positive change, challenged the status quo and re-invented the architecture of Hon. -

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2011 I Shell Sustainability Report 2011 Introduction

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2011 i Shell Sustainability Report 2011 Introduction CONTENTS ABOUT SHELL INTRODUCTION Shell is a global group of energy and petrochemical companies employing 90,000 people in more than 80 i ABOUT SHELL countries. Our aim is to help meet the energy needs of 1 INTRODUCTION FROM THE CEO society in ways that are economically, environmentally and socially responsible. OUR APPROACH Upstream 2 BUILDING A SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FUTURE Upstream consists of two organisations, Upstream International and Upstream Americas. Upstream searches for and recovers oil 3 SD AND OUR BUSINESS STRATEGY and natural gas, extracts heavy oil from oil sands for conversion 4 SAFETY into synthetic crudes, liqueƂ es natural gas and produces synthetic oil products using gas-to-liquids technology. It often works in joint 5 COMMUNITIES ventures, including those with national oil companies. Upstream 6 CLIMATE CHANGE markets and trades natural gas and electricity in support of its business. Our wind power activities are part of Upstream. Upstream 8 ENVIRONMENT International co-ordinates sustainable development policies and 9 LIVING BY OUR PRINCIPLES social performance across Shell. Downstream OUR ACTIVITIES Downstream manufactures, supplies and markets oil products and 10 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN ACTION chemicals worldwide. Our Manufacturing and Supply businesses include reƂ neries, chemical plants and the supply and distribution 11 KEY PROJECTS of feedstocks and products. Marketing sells a range of products 12 DELIVERING ENERGY RESPONSIBLY including fuels, lubricants, bitumen and liqueƂ ed petroleum 12 Natural gas gas for home, transport and industrial use. Chemicals markets 15 The Arctic petrochemicals for industrial customers. -

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

The Nigerian Crucible

THE NIGERIAN CRUCIBLE Politics and Governance in a Conglomerate Nation, 1977-2017 RICHARD JOSEPH PART TWO I: Challenges of the Third Republic1 The Guardian (Lagos), (1991) In the final sentences of my book, Democracy and Prebendal Politics in Nigeria: The Rise and Fall of the Second Republic, I spoke of my “moderate optimism” and expressed the wish: “After the completion of the current cycle of political rule by military officers, perhaps some author will have good reason to write of the political triumphs and temporary travails of the Third Republic.” The building of a “democracy that works,” the title of the first chapter of the book, is a very difficult enterprise. It is often easier to restrict debate and discussion, silence critics, issue commands, and insist on absolute fealty to those in charge. This easier route, however compelling it may appear, shares much of the responsibility for the deepening plight of the African continent. Thousands of Africans who would not simply obey, desired to have pride in their work and work-environment, wanted to speak their minds without fearing the official rap on the door, have fled to foreign lands, first a trickle of exiles, then a stream. Economic exiles eventually followed the intellectual political exiles; and soon many of Africa’s finest had drifted to the industrialized world, impoverishing the continent further. Just before I left the University of Ibadan to return to the United States in August 1979, Femi Osofisan, one of Nigeria’s brilliant intellectuals and writers, attended a small dinner party organized by friends and colleagues. -

$1.1Bln ■ Developing Nigerian Talent and Supply Chains

16 SHELL IN NIGERIA A team of employees at Shell ECONOMY 17 Nigeria Gas facility at Agbara, Ogun State Nigeria. POWERING NIGERIA’S 678k SPDCJV BARRELS OF OIL EQUIVALENT SNEPCo ECONOMY PER DAY PRODUCED IN 2019 Nigeria’s oil and gas resources can power a diverse economy, expand domestic industries and increase the prosperity of $1.5bln its people. In 2019, Shell Companies in $ IN TAXES AND ROYALTIES Nigeria paid about $1.5 billion3 in taxes IN 2019 (SPDC & SNEPCo) and royalties to the Nigerian government. With business interests from the oil and gas producing heartlands of the Niger Delta to the growing industries of Ogun State and Lagos, Shell Companies in Nigeria 3,000 provide technical expertise, a global perspective and EMPLOYEES strong governance that can unlock opportunities for Nigeria and Nigerians. ■ Prosperity through power. ■ A pipeline of projects. ■ Future opportunities in deep-water. $1.1bln ■ Developing Nigerian talent and supply chains. SPENT ON CONTRACTS TO NIGERIAN COMPANIES IN 2019 (SCiN) The Nigeria Briefing Notes update on activities and programmes undertaken by several Nigerian companies either wholly-owned by Shell or in which Shell has an interest. Together these are referred to as the Shell Companies in Nigeria (SCiN). Four of these are: ■ Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (SPDC); a wholly-owned Shell subsidiary, which operates an unincorporated joint venture (SPDC JV) in which SPDC holds a 30% interest. ■ Two other wholly-owned Shell subsidiaries; Shell Nigeria Exploration and Production Company Limited (SNEPCo) and Shell Nigeria Gas Limited (SNG). ■ And Nigeria Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG) Limited; an incorporated joint venture in which Shell has a 25.6% interest. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Shell.Reviews@Ceaa‐Acee.Gc.Ca

Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Shell.Reviews@ceaa‐acee.gc.ca October 1, 2012 Dear Joint Review Panel Secretariat, Re: Shell Jackpine Mine Expansion We are submitting this as a request to present evidence to the Joint Review Panel hearings. This letter documents our serious concerns regarding the proposed project. One of us (Anna Zalik) was born in Alberta, lived and worked in Edmonton through her late 20s and received her first degree from the University of Alberta. The other (Isaac ‘Asume’ Osuoka) was born in Nigeria’s Niger Delta where he later devoted most of his adult life to working with communities impacted by the oil industry. This letter is informed by our individual experiences and academic research on oil industry socio‐ecological practices since 1997 (Osuoka) and 2001 (Zalik) respectively, and collaborative research since 2008. From 2000 to the present Zalik conducted extensive field work in oil‐producing regions of Nigeria and Mexico. From 2005 onward she initiated research on the sociology of the oil and gas industry in the US and in Canada from onward, with field research visits conducted in Northern Alberta and British Columbia since 2008. This work has included interviews with community members, government agencies, NGOs and industry representatives. Both of us have presented research in various international fora. With regard to precedents set through previous Shell Jackpine EIA processes, several of which are now in the JRP public materials and analysed by the Pembina Institute and Ecojustice, Shell did not fulfill its earlier commitment to the Oil Sands Environmental Coalition (OSEC)1 to mitigate CO2 emissions. -

Socio-Economic and Political Activities of Southern Ijaw Local Government Area of Bayelsa State

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2017): 7.296 Socio-Economic and Political Activities of Southern Ijaw Local Government Area of Bayelsa State Sigah .F. 1, Otoro P.2, Omovwohwovie E. E.3 1 , 2Department of Public Administration, Federal Polytechnic Ekowe,Bayelsa State 3Department of Fisheries Technology, Federal Polytechnic Ekowe, Bayelsa State Abstract: Southern Ijaw Local Government Area is the largest local government area in Bayelsa State, and it is in the Niger Delta region of the country. This Study highlighted the social, economic and political activities in the local government area as to have a clear understanding about the wellbeing and politics of the people of Southern Ijaw Local Government Area of Bayelsa State Nigeria. 1. Introduction term........local government can only be characterized in such a way that it can be recognized as such different times 3 Local Government is widely recognized, as a veritable and places’’ instrument for the transformation and the delivery of social services to the people. It is also recognized as being strategic Let us at this point cite a few definitions of local government in facilitating the extension of democracy to the local level by some scholars and authors. “Local government has been by increasing the opportunities for political participation by defined as the lowest unit of administration to whose laws the grassroots population. It is as well widely regarded as and regulation, the communities who live in a defined being well situated to perform the above functions due to the geographical area and with common social and political ties 4 various advantages which it has over the other tiers of are subject’’ government and their field agencies. -

NON-FERROUS METALS a Survey of Their Production and Potential in the Developing Countries

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] $mz4 NON-FERROUS METALS A Survey of their Production and Potential in the Developing Countries UNITED NATIONS NON-FERROUS METALS (COPPER, ALUMINIUM. -

Shell: We Will Remember Ken Saro-Wiwa and Friends

Shell: We Will Remember Ken Saro-Wiwa and Friends "I and my colleagues are not the only ones on trial. Shell is here on trial and it is as well that it is represented by counsel said to be holding a watching brief. The Company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come and the lessons learnt here may prove useful to it for there is no doubt in my mind that the ecological war that the company has waged in the Delta will be called to question sooner than later and the crimes of that war be duly punished. The crime of the Company’s dirty wars against the Ogoni people will also be punished." Ken Saro- Wiwa - 1995 Thursday, 10 November marks the 10th Anniversary of the murder of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his eight colleagues, Baribor Bera, Saturday Dobee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbokoo, Barinem Kiobel, John Kpuinen, Paul Levura and Felix Nuate by the State of Nigeria for campaigning against the devastation of the Niger Delta by oil companies, especially Shell. They represented the “Movement for Survival of the Ogoni Peoples’.” Who is Ken Saro-Wiwa: Ken, was an academic, civil servant, businessman, author and most importantly at his death, a community activist. In 1990, Saro-Wiwa started to dedicate himself to the amelioration of the problems of the oil producing regions of the Niger Delta. Focusing on his homeland, Ogoni, he launched a non-violent movement for social and ecological justice - MOSOP. In this role he challenged the oil companies and the Nigerian government accusing them of waging an ecological war against the Ogoni and precipitating the genocide of the Ogoni people. -

The State and Migration of Nigerians Into the European Union to Live in Spain

The State and Migration of Nigerians Into the European Union to Live In Spain Matthew OKIRI OKEYIM The State and Migration of Nigerians Into the European Union to Live In Spain BY Matthew OKIRI OKEYIM BSc (Political Science) Ibadan Nigeria MSc (International Relations) Ibadan Nigeria DEA (social Welfare and Inequality) Alicante, Spain University of Alicante – Sociology II Department Doctorate Thesis Submitted to the University of Alicante, Spain Sociology October 2012. Professor La Parra, Daniel University of Alicante Department of Sociology II Spain. This thesis is dedicated to the Almighty God, Patrick OKEYIM, Janet OKEYIM and ZULINA ANGELA OKEYIM for their endless support and encouragement. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Professor Roberto ESCARRE and Andrew OJO encouraged me to enroll in the PhD Program in the University of Alicante. I remain ever grateful to them for facilitating my admission into the Program in 2006. Prof. Oscar SANTACREU, and Prof. Eva ESPINAR, Prof. Marie OSE, Anna MERCEDES, Fernando DIAZ ORUETA, Professor Marie OSE chemical Sciences, Alicia WYNNARD of the library services, Anna in the department office and other Professors in the Department especially during my first year of the Program I am very grateful to them. Professor Daniel LA PARRA who kindly agreed to supervise me from 2009 during my period of investigation has been excellent and wonderful. Prof. Daniel introduced me to the International Doctorate which resulted to my going to the Queen Mary University of London where I spent 3 months from September 2010 - December 2010 for a jointly International Doctorate Supervision. Prof. Nair, Director of Hispanic and Migration studies, Queen Mary University of London, who kindly accepted in spite of her tight schedule for a jointly supervision of this International Doctorate was also very wonderful during my 3 stays in the United Kingdom.