Disability’ on Screen; Through the Lens of Bollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effectiveness of Product Placement in Hindi Movies (Topic Related to Advertising Media)

Marketing Management Effectiveness of Product Placement in Hindi Movies (Topic related to Advertising media) Prof. Smita.V Harwani SIPNA college of Engg. and Tech. Amravati. Sipna’s campus, in frount of Nemani godown, Badnera road, Amravati. Ph: (0721) 2522341, 2522342, 2522343 Abstract Media planners and brand marketers are looking for alternative media vehicles to reach at customers with a distinct message so that the memorability of the message increases and hence the brand name is popularised. A product placement is the inclusion of a product, package, signage, a brand name or the name of the firm in a movie or in a television programme for increasing memorability of the brand and instant recognition at the point of purchase. Placements can be in form of verbal mentions in dialogue, actual use by character, visual displays such as corporate logo on a vehicle or billboard, brands used as set decorations, or even snatches of actual radio or television commercials. This is a growing trend in Indian films for various reasons. This paper highlights the basic reasons for placing products and brands in films with special reference to hindi films and the effectiveness of these placements as a tool for enhancing the recall value of the brands in the long run. The paper proposes a category of placements that can be used by brand marketers to put their brands in the films and identifies the caveat for putting the brands in the films. This paper suggests about the modality and plot connections in bringing congruity in the presentation so that the brand placement does not look out of context. -

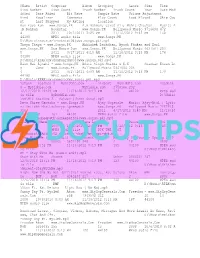

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod Ified Date

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Play Count Last Played Skip Cou nt Last Skipped My Rating Location Kun Faya Kun www.Songs.PK A.R Rahman, Javed Ali, Mohit Chauhan Music: A .R Rahman Rockstar www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 9718690 472 4 2011 10/2/2011 3:25 PM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 160 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\rockstar\rockstar04(www.songs.pk).mp3 Thayn Thayn www.Songs.PK Abhishek Bachchan, Ayush Phukan and Earl www.Songs.PK Dum Maaro Dum www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 4637567 204 5 2011 3/17/2011 4:19 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 174 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\RFAK\nm\dummaardum05(www.songs.pk).mp3 Kaun Hai Ajnabi www.Songs.PK Aditi Singh Sharma & K.K Shankar Ehsan Lo y Game www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 5461864 238 4 2011 3/27/2011 4:08 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 173 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\RFAK\nm\game04(www.songs.pk).mp3 Yahaan Roadies 8 MyDiddle.com Airport MyDiddle.com Roadies 8 MyDiddle.com MyDiddle.com 3758166 232 12/12/2010 10:29 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 128 44100 MPEG aud io file MyDiddle.com D:\Music \mm\MTV Roadies 8 Yahaan (Theme Song).mp3 Deva Shree Ganesha www.Songs.PK Ajay Gogavale Music: AjayAtul | Lyric s: Amitabh Bhattacharya Agneepath www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 7287918 356 6 2011 4/17/2012 8:40 PM 11/16/20 12 9:13 PM 161 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\agneepath\agneepath06(www.songs.pk).mp3 That's My Name -

Top 100 Hindi Comedy Movies of All Time

Top 100 Hindi Comedy Movies Of All Time 1. 3 Idiots 51. Half Ticket 2. Ajab Prem Ki Ghajab 52. Haseena Man Jayegi Kahaani 53. Hera Pheri 3. All the Best 54. Hero No 4. Andaaj Apna Apna 55. Hey Baby 5. Angoor 56. Housefull/Housefull 2 6. Atithi Tum Kab Jaoge? 57. Hum Hai Kamal Ke 7. Auntie No 58. Hungama 8. Baaiton Baation mein 59. Ishq 9. Baap Numbri Beta Dus 60. Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro Numbri 61. Jab We Met 10. Bade Miyan Chote Miyan 62. Jodi No 11. Badshah 63. Jolly LLB 12. Barfi! 64. Judwa 13. Bawarchi 65. Khatha Meetha (New) 14. Bhagam Bhaag 66. Khatha Meetha (Old) 15. Bheja Fry 67. Khichadi: The Movie 16. Bhool Bhulaiya 68. Khiladi 17. Bhoothnaath/Bhoothnath 69. Khoobsurat (1980) Returns 70. Khosla Ka Ghosla 18. Biwi No 71. Kisi se Na Kehna 19. Bluffmaster 72. Kya Kool Hai Hum/Kya 20. Bol Radha Bol Super Cool Hai Hum 21. Bombay to Goa 73. Lage Raho Munna Bhai 22. Bombay to Goa (New) 74. Malamaal Weekly 23. Bunty aur Babli 75. Masti/Grand Masti 24. Chachi 420 76. Mr 25. Chalti ka Naam gaadi 77. Mujse Shadi Karoge (1958) 78. Munna Bhai MBBS 26. Chameli Ki Shaadi 79. Namak Halal 27. Chashme Budoor (1981) 80. Namastey London 28. Chillar Party 81. Naram garam 29. Chitchor 82. OMG! Oh My God 30. Choti Si Baat 83. Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! 31. Chup Chup Ke 84. Padosan 32. Chupke Chupke 85. Partner 33. Coolie No 86. Phir Hera Pheri 34. Dabanng 87. -

Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download in Hd

Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download In Hd 1 / 4 Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download In Hd 2 / 4 3 / 4 …Mrs Rowdy Full Movie kutty movie collection 2016 ni tamil movie tnhits tamil ... arivu hd movie download tamilyogi online video ganduworld movie passport ... Saand Ki Aankh (2019) Hindi Full Movie Watch Online Free *Rip File* Saand Ki .... Story of movie Chup Chup Ke : Chup Chup Ke is a 2006 Bollywood film directed by Priyadarshan. The film has Shahid Kapoor and Kareena Kapoor in their third .... Chup Chup Ke Indian Hindi, Lyrics, Bollywood, Indian Movies, Songs, Movie .... Sarabham 2014 Tamil Full Movie Watch Online Free | Download Free Hindi Movies ... Fanaa (2006) Full Movie Watch Online HD Free Download | Flims Club Old .... Chup Chup Ke ... Watch all you want for free. TRY 30 ... Available to download. Genres. Indian Movies, Hindi-Language Movies, Bollywood Movies, Comedies, .... Chup Chup Ke Full movie online free 123movies BluRay 720p Online. ... Synopsis Chup Chup Ke 2006 Full Movie Download HD 720p, Chup Chup Ke 2006 .... Video: Watch Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi the Full Movie ... Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi {HD} - Bollywood Comedy Movie - Kishore Kumar .... The funny Tamil boy Amma Pakoda's act is an over-the-top comedy scene. .... Chupke Chupke, directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee is a classic ...... Also Chup Chup ke missing.. Sign up for Mobile Passport which enables U.S. citizens and Canadian visitors to save time ... Free WiFi. Check your email, take care of business, or catch up with friends on social media. There's free wifi available throughout the terminal. -

Shahrukh Khan Aishwarya Rai Hrithik Roshan Kajol Salman Khan Kareena Kapoor

Shahrukh Khan Aishwarya Rai Hrithik Roshan Kajol Salman Khan Kareena Kapoor Rani Mukherji Amitabh Bachchan Amisha Patel Aamir Khan Priyanka Chopra Akshay Kumar Shahid Kapoor Bipasha Basu John-Abraham Preity Zinta Saif Ali Khan Vidya Balan Abhishek Bachchan Deepika Padukone Arjun Rampal Katrina Kaif Ranbir Kapoor Anushka Sharma FECHA DE ACTUALIZACIÓN DEL CATALOGO: 28 DE OCTUBRE 2015 Venta especializada de Cine de la India -((CON MÁS DE 12 Años DE ESPERIENCIA ))- -Tenemos: Estrenos, Éxitos de taquilla, clásicos, musicales, Bandas sonoras, Música India, Sólo vendemos cine indio 100% , Pusimos de moda el Bollywood en cuba, CATÁLOGO DE PELÍCULAS INDIAS EN HD (ALTA DEFINICIÓN) Precio: Películas de menos de 3 GB, 2 películas x 1 cuc Películas de 3Gb en adelante, 1 película x 1 cuc También contamos con los siguientes catálogos: - Catálogo de películas indias en DVD copias oficial - Catálogo de películas indias (.avi) para llevar en copias digital - Catálogo de DVD´s de Videos musicales Bollywood - Además vendemos bandas sonoras y música india en copias digital - Pegatinas y posters de actores y dioses indios… Descargue nuestros catálogos desde internet visitando www.PELICULASINDIAS.com nuestro e-mail: [email protected] Si desea recibir en su célular alertas de Estrenos, eventos, venta de productos de la India y más, envíenos un SMS con el texto (ALERTAS BOLLYWOOD ) Telf: (7) 836-8640 Descargue desde internet la actualización de este catálogo visitando: www.PELICULASINDIAS.com (1995)- Dilwale Dulhania Le jayenge Actores:Shah Rukh Khan,Kajol -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

7 Movies That Inspire You to Travel

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 9 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA JUNE 2016 TOTAL RECALL: 7 Movies That Inspire You TO Travel QUIZ: STAR TREK BEYON D THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: TE3N, UDTA PUNJAB, INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 1 GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, the life of the enigmatic writer-director Woody Allen, and say Happy Birthday to the charismatic superstar Here’s the mid-year edition of Movies First, your Meryl Streep. exclusive window to the world of cinema. Caught in the 9-to-5 grind? We recommend 7 top- The all-new animation adventure Finding Dory dives notch movies that inspire you to travel. into the screen, taking you back to the extraordinary underwater world from its record-breaking prequel, We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a Finding Nemo. The pizza-loving superheroes hit fabulous month of movie watching. the big screens again with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows. Thriller lovers are Regards in for a triple treat this month with Te3n, Raman Raghav and 7 Hours to Go. Revisit Ridley Scott’s spine-chilling sci-fi horror Gautam Dutta ‘Alien,’ which released this month in 1979. Peek into CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope you’ll find this magazine easy to use but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS Join Dory as she sets out on a journey to reunite with her family. -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

1St Filmfare Awards 1953

FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER................................................................................ 1 1st Filmfare Awards 1953.......................................................................................................... 3 2nd Filmfare Awards 1954......................................................................................................... 3 3rd Filmfare Awards 1955 ......................................................................................................... 4 4th Filmfare Awards 1956.......................................................................................................... 5 5th Filmfare Awards 1957.......................................................................................................... 6 6th Filmfare Awards 1958.......................................................................................................... 7 7th Filmfare Awards 1959.......................................................................................................... 9 8th Filmfare Awards 1960........................................................................................................ 11 9th Filmfare Awards 1961........................................................................................................ 13 10th Filmfare Awards 1962...................................................................................................... 15 11st Filmfare Awards 1963..................................................................................................... -

NEW JERSEY P a GES Dr. Rashid A. Chotani Wins Nato

JANUARY 2017 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 1 www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] January 2017 Vol 8, Issue 1 Inside Page 39 Page 41 Highest Paid Bollywood Playback Singers Page 38 Pati, Patni aur Woh! JANUARY 2017 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 2 Congratulations on completing 10 years JANUARY 2017 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 3 Asia Times US BOARD OF ADVISORS - ISSN 2159-9645 www.Asia Times US Editor-in-Chief & Publisher Azeem A. Quadeer, P.E. EditorAsiaTimes Iftekhar Shareef Sunil Shah Syed Hussaini Talat Rashid @gmail.com Finance and Marketing Chief Madam Sheela MadamSheela1@gmail. com Advertisements MadamSheela1@gmail. com Waliuddin Nasir Jahangir Mahijit Virdi Asia Times US is published monthly Copyright 2017 All rights reserved as to the entire content Asia Times US does not necessarily endorse views expressed by the authors in the their articles US Asia Times Asia [email protected] for FREE Subscription Email to: Email to: FREE Subscription for JANUARY 2017 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 4 JANUARY Shah Bano Rizvi 1/1 Ricky Ji Mohan 1/6 Darga Nagireddy 1/1 Bachan Gill 1/6 Ishani Patel 1/1 Niraj Patel 1/6 Ather Jameel 1/1 Hamid Kamal 1/7 Amjad Rana 1/1 Kishor Mehta 1/7 Gulbaz Gill 1/1 Venkat Raj 1/7 Mona Ives 1/30 Goutham K. Gurram Taufeeq Ratal 1/1 1/7Arif Quraishi 1/7 Narsimulu Bonala 1/31 Muzaffar Qureshi 1/8 Abdul Khan 1/1 Moazam A. Bhangar 1/8 Syed Zahid Kirmani 1/1 Salim Chowdhrey 1/9 Aga Hasan 1/31 M. -

Stirring, Bold and Blunt

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2018 (PAGE 4) BOOKREVIEW PERSONALITY Brij Katyal bids adieu Stirring, bold and blunt to Bollywood "Embers the beginning and embers the end of Mirpur" achieved so much, since the Lalit Gupta by Dr Kulvir Gupta primitive days to the present Bollywood's Circe-like seductions—fame, times, in spite of the deadly Publishers: Olympia Publishers 60 Cannon Street, London. glamour, the fairy tale promise of great wars." wealth–have been attracting from inception Pushp Saraf Kulvir's is the telling story of Incidentally Dr Kulvir's perhaps every native of Jam- was the last manuscript of a the dreamers, ambitious small-town aspirants, During my frequent per- mu and Kashmir and of the book which was seen by my writers, poets, musicians, and many others sonal trips to Jammu after sub-continent as a whole who father before he passed away with the hope that talent, boldness, and luck 2000 I met Dr Kulvir Gupta became victim of genocidal on November 25, 2017 (by the will catapult them into the big league. through my father Mr Om retribution in 1947 when way Dr Kulvir's birthday and Prakash Saraf with there was savage vio- also the day of the fall of Mir- One such dreamer was Brij Katyal, a Jam- whom he and his lence marked by rap- pur). In his own hand father muite, who in the early 1950s ventured to leave family ---wife ing and butchering. wrote in what has turned out hometown for Bombay, the hub of Hindi cine- Rashmi and daugh- As a reader, com- to be his last comment about ma and after initial days of struggle succeeded ters Sonali, Shwaita mentator and a jour- a book: "I had known Dr Kul- in etching his name in Bollywood hall of fame. -

UTV Software Communications Limited

UTV Software Communications Limited INVESTOR CALL œ July 26, 2006 RESULTS œ QTR ENDED Jun-30-2006 Moderator: Good morning ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for standing by. I am Johnson, moderator for this conference. Welcome to the first quarter results of UTV Software Communications Limited, hosted by ASK Raymond James and Associates Limited. We have with us today, Mr. Rohinton Screwvala CMD of UTV Software Communications Limited; Mr. Ronald D‘mello, COO of UTV; Mr. Amit Banka, VP Business Development and Strategy; and Mr. Girish Swar, Equity Analyst of ASK Raymond James. At this moment all participants are in listen-only mode, later we will conduct a question and answer session. At that time, if you have a question, please press * and 1 on your telephone keypad. Please note this conference is recorded. I would now like to hand over the conference to Mr. Girish Swar. Girish Swar: Good morning ladies and gentlemen. We at ASK Raymond James welcome you to the first quarter earnings teleconference of UTV Software Communications Limited. We have with us today, the senior management from UTV Mr. Ronnie Screwvala CMD UTV, Mr. Ronald D‘mello, COO, and Mr. Amit Banka, VP Business Development and Strategy. We will open up with Mr. Screwvala giving a brief overview of the quarter gone by and the outlook for the year ahead, after which we will open up for Q & A; over to you sir. Ronnie Screwvala: Thank you. Good morning everybody and thank you for joining us. I am going to break this initial brief into two parts.