Circular Economy Action Agenda for Textiles Results from the Insights of and Discussions with the Following Organizations and Experts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

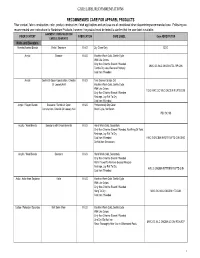

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Review Article

Indian Journalof Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 29, December 2004, pp. 483-492 Review Article Development and processing of lyocell R B Chavan Department of Textile Technology, Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi 110 016, India and A K Patra' The Technological Institute of Textile & Sciences, Bhiwani 127 02 1, India Received 20 June 2003; revised received and accepted December 2003 5 An account of Iyocell, covering the hindsight of its development and available brands has been reported. This wonder fibre surpasses all other cellulosic fibres in terms of properties, aesthetics and. quite importantly. ecology in manufacturing. Among the various names with which Iyocell is available. Tencel and Tencel A 100 are the prominent and widely used. Be sides dealing with the various attributes of Iyocell, the options for wet treatment of the fibre with reference to steps of proc essing. suitability of dyes and process parameters have also been addressed. Keywords: Fibrillation, Lyocell, Peach-skin effect. Tencel. Tencei A 100 IPC Code: CI. DO 1 F 2/00. D2 1 H 13/08 I nl. 7 1 Introduction solved solids. The viscose rayon manufacturing proc ' There has been a growing demand for absorbent fi ess is also energy-intensive. Besides this, viscose bres with the need hinging on comfort and fashion. rayon production has high labour demand, mainly due Since cotton production can not go beyond a particu to the complexity and number of steps involved in lar level due to limited land availability, the other ob converting pulp into rayon fibre. vious options are viscose and the likes. But again, Among the modified viscose fibres, high wet with the increasing awareness of ecofriendly con modulus (HWM) rayon involves relatively simple and cepts, viscose is not quite highly rated because its economical manufacturing process, but the zinc used manufacturing plants have inherent problem of efflu in this process is a known pollutant. -

Uncompromising Protection. Unparalleled Comfort

UNCOMPROMISING PROTECTION. UNPARALLELED COMFORT. Discover Our North American Flash Fire Product Portfolio. 1 Our Commitment to FR Worker Safety At Westex by Milliken, worker safety is our priority. We’re leaders in secondary arc rated (AR) and flame resistant (FR) protection, backed by 150 years of Milliken innovation—and we go further than anyone else to ensure workers are protected, comfortable and able to return home safely each night. At the heart of our commitment is engineering: scientific expertise and advanced, custom-made equipment that guarantees flame resistance for the life of the garment. Market proven, with tens of millions of yards out in the field, our fabrics don’t just meet standards—they integrate safety and comfort in ways that were once considered impossible. But we don’t stop there with engineering and innovation. Through extensive educational outreach, we’ve helped millions of workers better understand arc flash, flash fire and other thermal hazards. Because helping workers feel confident in any and every condition comes down to innovation, exceptional engineering and education. For more information, visit westex.com/fabrics Details on Page 7 2 Westex protection delivers on the flash fire standard. The Need The Standard In oil, gas, chemical and petrochemical industries, the The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) developed threat of flash fire exposures has necessitated the use NFPA® 2112 as the industry standard for flame-resistant of flame resistant clothing. Flame resistant clothing will garments designed to protect against Flash Fire. The official minimize burn injury and provide the worker a few seconds title for NFPA® 2112 was recently updated to “Standard on of escape time. -

Speciality Fibres

Speciality Fibres wool - global outlook what makes safil tick? nature inspires innovation in fabric renaissance for speciality fibre china rediscovers south african mohair who supplies the supplier? yarn & top dyeing sustainable wool production new normal in the year of the sheep BUYERS GUIDE TO WOOL 2015-2016 Welcome to Wool2Yarn Global - we have given our publication a new name! This new name reflects the growing number of yarn manufactures that are now an important facet of this publication. The new name also better reflects our expanding global readership with a wide profile from Acknowledgements & Thanks: wool grower to fabric, carpet and garment manufacturers in over 60 Alpha Tops Italy countries. American Sheep Association Australian Wool Testing Authority Our first publication was published in Russian in1986 when the Soviet British Wool Marketing Board Union was the biggest buyer of wool. After the collapse of the Soviet Campaign for Wool Canadian Wool Co-Operative Union this publication was superseded by a New Zealand / Australian Cape Wools South Africa English language edition that soon expanded to include profiles on China Wool Textile Association exporters in Peru, Uruguay, South Africa, Russia, UK and most of Federacion Lanera Argentina International Wool Textile Organisation Western Europe. Interwoollabs Mohair South Africa In 1999 we further expanded our publication list to include WOOL Nanjing Wool Market EXPORTER CHINA (now Wool2Yarn China) to reflect the growing New Zealand Wool Testing Authority importance of Asia and in particular China. This Chinese language SGS Wool Testing Authority magazine is a communication link between the global wool industry Uruguayan Wool Secretariat Wool Testing Authority Europe and the wool industry in China. -

Natural Fibers and Fiber-Based Materials in Biorefineries

Natural Fibers and Fiber-based Materials in Biorefineries Status Report 2018 This report was issued on behalf of IEA Bioenergy Task 42. It provides an overview of various fiber sources, their properties and their relevance in biorefineries. Their status in the scientific literature and market aspects are discussed. The report provides information for a broader audience about opportunities to sustainably add value to biorefineries by considerin g fiber applications as possible alternatives to other usage paths. IEA Bioenergy Task 42: December 2018 Natural Fibers and Fiber-based Materials in Biorefineries Status Report 2018 Report prepared by Julia Wenger, Tobias Stern, Josef-Peter Schöggl (University of Graz), René van Ree (Wageningen Food and Bio-based Research), Ugo De Corato, Isabella De Bari (ENEA), Geoff Bell (Microbiogen Australia Pty Ltd.), Heinz Stichnothe (Thünen Institute) With input from Jan van Dam, Martien van den Oever (Wageningen Food and Bio-based Research), Julia Graf (University of Graz), Henning Jørgensen (University of Copenhagen), Karin Fackler (Lenzing AG), Nicoletta Ravasio (CNR-ISTM), Michael Mandl (tbw research GesmbH), Borislava Kostova (formerly: U.S. Department of Energy) and many NTLs of IEA Bioenergy Task 42 in various discussions Disclaimer Whilst the information in this publication is derived from reliable sources, and reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, IEA Bioenergy, its Task42 Biorefinery and the authors of the publication cannot make any representation of warranty, expressed or implied, regarding the verity, accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of the information contained herein. IEA Bioenergy, its Task42 Biorefinery and the authors do not accept any liability towards the readers and users of the publication for any inaccuracy, error, or omission, regardless of the cause, or any damages resulting therefrom. -

Colour and Textile Chemistry—A Lucky Career Choice

COLOUR AND TEXTILE CHEMISTRY—A LUCKY CAREER CHOICE By David M. Lewis, The University of Leeds, AATCC 2008 Olney Award Winner Introduction In presenting this Olney lecture, I am conscious that it should cover not only scientific detail, but also illustrate, from a personal perspective, the excitement and opportunities offered through a scientific career in the fields of colour and textile chemistry. The author began this career in 1959 by enrolling at Leeds University, Department of Colour Chemistry and Dyeing; the BSc course was followed by research, leading to a PhD in 1966. The subject of the thesis was "the reaction of ω-chloroacetyl-amino dyes with wool"; this study was responsible for instilling a great enthusiasm for reactive dye chemistry, wool dyeing mechanisms, and wool protein chemistry. It was a natural progression to work as a wool research scientist at the International Wool Secretariat (IWS) and at the Australian Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) on such projects as wool coloration at room temperature, polymers for wool shrink-proofing, transfer printing of wool, dyeing wool with disperse dyes, and moth-proofing. Moving into academia in 1987 led to wider horizons bringing many new research challenges. Some examples include dyeing cellulosic fibres with specially synthesised reactive dyes or reactive systems with the objective of achieving much higher dye-fibre covalent bonding efficiencies than those produced using currently available systems; neutral dyeing of cellulosic fibres with reactive dyes; new formaldehyde-free crosslinking agents to produce easy-care cotton fabrics; application of leuco vat dyes to polyester and nylon substrates; cosmetic chemistry, especially in terms of hair dyeing and bleaching; security printing; 3-D printing from ink-jet systems; and durable flame proofing cotton with formaldehyde-free systems. -

Sustaining PICA for Future NASA Robotic Science Missions Including NF-4 and Discovery

Sustaining PICA for future NASA Robotic Science Missions including NF-4 and Discovery Mairead Stackpoole Ethiraj Venkatapathy Steven Violette NASA Ames Research Center NASA Ames Research Center Fiber Materials Inc. Moffett Field, CA 94035 Moffett Field, CA 94035 Biddeford, ME 04005 650-604-6199 650-604-4282 207-282-7062 Margaret.m.stackpoole.nasa.gov ethiraj.venkatapathy- [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Phenolic Impregnated Carbon Ablator (PICA), was protected from the heat by a single piece net cast PICA invented in the mid 1990’s, is a low-density ablative thermal heatshield. OSIRIS REx, the first US mission to bring back protection material proven capable of meeting sample return samples from an asteroid (Bennu) to Earth, also uses a single mission needs from the moon, asteroids, comets and other piece PICA heatshield very similar to the Stardust design. In unrestricted class V destinations as well as for Mars. Its low addition to Stardust and OSIRIS-REx, PICA was used as the density and efficient performance characteristics have proven effective for use from Discovery to Flag-ship class missions. It is heatshield on the Mars Science Lab (MSL) in a tiled important that NASA maintain this thermal protection material configuration. The Mars 2020 mission heatshield design will capability and ensure its availability for future NASA use. The follow that of MSL and again use PICA in a tiled rayon based carbon precursor raw material used in PICA arrangement. A variant of PICA known as PICA-X is used preform manufacturing has experienced multiple supply chain as the heatshield TPS on the Dragon capsule. -

Responsible Production in the Lenzing Group

www.lenzing.com Responsibleproduction Lenzing Group Focus Responsible Production Responsible Production 2019Content Overview 4 Biorefinery – pulp production in the Lenzing Group 5 Biorefinery plant in Lenzing, Austria 6 Biorefinery plant in Paskov, Czech Republic 6 Pulp bleaching in the Lenzing Group 7 Overview of fiber technologies 8 Two-stage production process 9 EU Ecolabel 10 Lenzing’s viscose and modal production process 11 Lenzing’s responsible viscose criteria 12 Closing the loops in the viscose process: best practice 14 Lenzing’s lyocell production process 15 Further technologies 17 REFIBRA™ technology 17 Eco Filament technology 18 LENZING™ Web Technology 18 Fiber types 19 Shortcut fibers 19 Trilobal fibers 19 Incorporation of additives into the spinning mass 19 Definitions/glossary 20 References & suggestions for further reading 22 Focus Responsible Production Lenzing Group 2 Responsibleproduction This focus paper “Responsible Production” describes the biorefinery and fiber production processes. It provides an overview of the Lenzing Group’s manufacturing processes with particular regard to environmental aspects. Lenzing Group Focus Responsible Production Overview Forest Wood Pulp Fiber In recent years, interest in wood-based cellulosic fibers of over 90 percent, lower impurity levels, be bleached to a high- has increased due to their sustainability credentials. er level of brightness and have a more uniform molecular weight When the source of raw material is from sustainable for- distribution. estry, as proven by forest certificates, and state-of-the-art production processes are applied, wood-based cellulosic The Lenzing Group produces more than half of the pulp it requires fibers can have a very favorable environmental footprint. at its sites in Lenzing (Austria) and Paskov (Czech Republic). -

NARC Rayon Replacement Program for the RSRM Nozzle, Phase IV Qualification and Implementation Status

NARC Rayon Replacement Program for the RSRM Nozzle, Phase IV Qualification and Implementation Status M. Reed Haddock*, Gary M. Wendelf, Roger V. Cook#, ATK Thiokol Inc., Brigham City, Utah 84302 Abstract The Space Shuttle NARC Rayon Replacement Program has down-selected Enka rayon as a replacement for the obsolete NARC rayon in the nozzle carbon cloth phenolic (CCP) ablative insulators. Full qualification testing of the Enka rayon-based carbon cloth phenolic is underway, including processing, thmal/structural properties, and hot-fire subscale tests. Required thermal-structural capabilities, together with confidence in erosiodchar performance in simulated and subscale hot fire tests such as Wright-Patterson Air Force Base Laser Hardened Materials Evaluation Laboratory testing, NASA-MSFC 24-inch motor tests, NASA-MSFC Solid Fuel Torch - Super Sonic Blast Tube, NASA-MSFC Plasma Torch Test Bed, ATK Thiokol Forty Pound Charge and NASA-MSFC MNASA justified the testing of the new Enka-rayon candidate on full-scale static test motors. The first RSRM full-scale static test motor nozzle, fabricated using the new Enka rayon-based CCP, was successfully demonstrated in June 2004. Two additional static test motors are planned with the new Enka rayon in the next two years along with additional A-basis property characterization. Process variation or “comer-of-the-box” testing together with cured and uncured aging studies are also planned as some of the pre-flight implementation activities with 5-year cured aging studies over-lapping flight hardware fabrication. Nomenclature NARC = North American Rayon Corporation CCP = carbon cloth phenolic RSRM = reusable solid rocket motor LHMEL = laser hardened materials evaluation laboratory PlTB = plasma torch testbed FPC = forty pound charge motor MSFC = Marshall Space Flight Center SFT = solid fuel torch SSBT = super sonic blast tube SGL= SGL Polycarbon NECP = National Electrical Carbon Products (formerly NSP) NSP = National Specialty Products UK = United Kingdom * Design Engineer, Nozzle Ablatives, P.O. -

Preparation of Fibrillated Cellulose Nanofiber from Lyocell Fiber and Its

materials Article Preparation of Fibrillated Cellulose Nanofiber from Lyocell Fiber and Its Application in Air Filtration Jin Long 1, Min Tang 2,*, Yun Liang 1 and Jian Hu 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Pulp and Paper Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510641, China; [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (J.H.) 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota—Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-612-840-8230 Received: 9 July 2018; Accepted: 27 July 2018; Published: 29 July 2018 Abstract: Ambient particulate matter less than 2.5 µm (PM2.5) can substantially degrade the performance of cars by clogging the air intake filters. The application of nanofibers in air filter paper can achieve dramatic improvement of filtration efficiency with low resistance to air flow. Cellulose nanofibers have gained increasing attention because of their biodegradability and renewability. In this work, the cellulose nanofiber was prepared by Lyocell fiber nanofibrillation via a PFI-type refiner, and the influence of applying a cellulose nanofiber on filter paper was investigated. It was found that the cellulose nanofibers obtained under 1.00 N/mm and 40,000 revolutions were mainly macrofibrils of Lyocell fiber with average fiber diameter of 0.8 µm. For the filter papers with a different nanofiber fraction, both the pressure drop and fractional efficiency increased with the higher fraction of nanofibers. The results of the figure of merit demonstrated that for particles larger than 0.05 µm, the figure of merit increased substantially with a 5% nanofiber, but decreased when the nanofiber fraction reached 10% and higher. -

Brands Table

CHANGING MARKETS * Changing Markets does not consider an email response without answers as engagement. YES NON-APPLICABLE NO MENTION DIDN‘T ENGAGE ON THE WEBSITE ROADMAP SIGNATORY ** Parent group PVH Corp engaged but did not specify it was on behalf of its brands *** On % of viscose, brands have reported on their proportion of viscose very differently, with some including both pure viscose and viscose blends and others appearing to report only pure viscose. **** MRSL (Manufacturing Restricted Substance List) provides brands, retailers, suppliers and manufacturers with acceptable limits of restricted substances in chemical formulations which are used DATE OF PUBLISHING: 18/11/2020 in the raw material and product manufacturing processes DESIGN: TOSHI.LTD- PIETRO BRUNI NO NO VISCOSE ***** ZDHC (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals) initiative includes colaition of brands supporting safer chemical management practices across the value chain DIDN‘T DISCLOSE SPECIFIC POLICY ZDHC SIGNATORY GREENPEACE DETOX ****** ZDHC MMCF: ZDHC came up with Guidelines for responsible production of man-made cellulosic fibres TO SEE THE FULL TABLE, VISIT: ******* Greenpeace Detox Campaign/Detox Catwalk was launched in 2011 to expose the direct links between global clothing brands, their suppliers and toxic water pollution around the world. Many brands signed up to a ‘Detox Pledge’ to eliminate the emission of hazardous chemicals in their supply chain by 2020. Where do brands stand on viscose ? LEVELS FRONTRUNNERS COULD DO BETTER TRAILING BEHIND RED ZONE www.dirtyfashion.info RAW MATERIAL MANUFACTURING AND PROCESSING TRANSPARENCY ABOUT VISCOSE SUPPLIERS SOURCING BRAND GROUP ENGAGED 2020? % OF VISCOSE VISCOSE POLICY (IF ANY) CANOPY STYLE MEMBER? CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT 2020 DISCLOSURE TO CHANGING MARKETS? DISCLOSURE ON WEBSITE? DISCLOSURE PLAN? C&A communicated that it sources viscose filament from Enka and viscose fibre from Birla and Lenzing. -

NARC Rayon Replacement Program for the RSRM Nozzle, Phase IV Qualification and Implementation Status

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20050206415 2019-08-29T20:37:57+00:00Z NARC Rayon Replacement Program for the RSRM Nozzle, Phase IV Qualification and Implementation Status M. Reed Haddock*, Gary M. Wendelf, Roger V. Cook#, ATK Thiokol Inc., Brigham City, Utah 84302 Abstract The Space Shuttle NARC Rayon Replacement Program has down-selected Enka rayon as a replacement for the obsolete NARC rayon in the nozzle carbon cloth phenolic (CCP) ablative insulators. Full qualification testing of the Enka rayon-based carbon cloth phenolic is underway, including processing, thmal/structural properties, and hot-fire subscale tests. Required thermal-structural capabilities, together with confidence in erosiodchar performance in simulated and subscale hot fire tests such as Wright-Patterson Air Force Base Laser Hardened Materials Evaluation Laboratory testing, NASA-MSFC 24-inch motor tests, NASA-MSFC Solid Fuel Torch - Super Sonic Blast Tube, NASA-MSFC Plasma Torch Test Bed, ATK Thiokol Forty Pound Charge and NASA-MSFC MNASA justified the testing of the new Enka-rayon candidate on full-scale static test motors. The first RSRM full-scale static test motor nozzle, fabricated using the new Enka rayon-based CCP, was successfully demonstrated in June 2004. Two additional static test motors are planned with the new Enka rayon in the next two years along with additional A-basis property characterization. Process variation or “comer-of-the-box” testing together with cured and uncured aging studies are also planned as some of the pre-flight implementation