“Life”: Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse's Reception Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

RHETORIC and RATIONALITY Steve Mackey

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 9, no. 1, 2013 RHETORIC AND RATIONALITY Steve Mackey ABSTRACT: The dominance of a purist, ‘scientistic’ form of reason since the Enlightenment has eclipsed and produced multiple misunderstandings of the nature, role of and importance of the millennia-old art of rhetoric. For centuries the multiple perspectives conveyed by rhetoric were always the counterbalance to hubristic claims of certainty. As such rhetoric was taught as one of the three essential components of the ‘trivium’ – rhetoric, dialectic and grammar; i.e. persuasive communication, logical reasoning and the codification of discourse. These three disciplines were the legs of the three legged stool on which western civilisation still rests despite the perversion and muddling of the first of these three. This essay explains how the evisceration of rhetoric both as practice and as critical theory and the consequent over- reliance on a virtual cult of rationality has impoverished philosophy and has dangerously dimmed understandings of the human condition. KEYWORDS; Rhetoric; Dialectic; Rationality; Enlightenment; Philosophy; Communication; C.S.Peirce: Max Horkheimer; Theodor Adorno; Jürgen Habermas; John Deely THE PROBLEM There are many criticisms of the rationalist themes and approaches which burgeoned during and since the Enlightenment. This paper enlists Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973) and Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969), John Deely (1942 – ) and Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 –1914), along with some leading Enlightenment figures themselves in order to mount a critique of the fate of the millennia-old art of rhetoric during that revolution in ways of thinking. The argument will be that post-Enlightenment over- emphasis on what might variously be called dialectic, logic or reason (narrowly understood) has dulled understanding of what people are and how people think. -

The Concept of the Global Subject in Adorno

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers November 2019 The Concept of The Global Subject In Adorno Sebastian Kanally [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kanally, Sebastian, "The Concept of The Global Subject In Adorno" (2019). Major Papers. 99. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/99 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Concept of The Global Subject in Adorno By Sebastian Kanally A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2019 © 2019 Sebastian Kanally The Concept of the Global Subject in Adorno by Sebastian Kanally APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ J. Noonan Department of Philosophy ______________________________________________ D. Cook, Advisor Department of Philosophy August 30, 2019 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis and that no part of this thesis has been published or submitted for publication. I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, my thesis does not infringe upon anyone’s copyright nor violate any proprietary rights and that any ideas, techniques, quotations, or any other material from the work of other people included in my thesis, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices. -

Vitalism and the Scientific Image: an Introduction

Vitalism and the scientific image: an introduction Sebastian Normandin and Charles T. Wolfe Vitalism and the scientific image in post-Enlightenment life science, 1800-2010 Edited by Sebastian Normandin and Charles T. Wolfe Springer, forthcoming 2013 To undertake a history of vitalism at this stage in the development of the ‘biosciences’, theoretical and other, is a stimulating prospect. We have entered the age of ‘synthetic’ life, and our newfound capacities prompt us to consider new levels of analysis and understanding. At the same time, it is possible to detect a growing level of interest in vitalistic and organismic themes, understood in a broadly naturalistic context and approached, not so much from broader cultural concerns as in the early twentieth century, as from scientific interests – or interests lying at the boundaries or liminal spaces of what counts as ‘science’.1 The challenge of understanding or theorizing vitalism in the era of the synthetic is not unlike that posed by early nineteenth-century successes in chemistry allowing for the synthesis of organic compounds (Wöhler), except that now, whether the motivation is molecular-chemical, embryological or physiological,2 we find ourselves asking fundamental questions anew. What is life? How does it differ from non-living matter? What are the fundamental processes that characterize the living? What philosophical and epistemological considerations are raised by our new understandings?3 We are driven to consider, for example, what metaphors we use to describe living processes as our knowledge of them changes, not least since some of the opprobrium surrounding the term ‘vitalism’ is also a matter of language: of which terms one 1 Gilbert and Sarkar 2000, Laublichler 2000. -

Averroes's Dialectic of Enlightenment

59 AVERROES'S DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT. SOME DIFFICULTIES IN THE CONCEPT OF REASON Hubert Dethier A. The Unity ofthe Intellect This theory of Averroes is to be combated during the Middle ages as one of the greatest heresies (cft. Thomas's De unitate intellectus contra Averroystas); it was active with the revolutionary Baptists and Thomas M"Unzer (as Pinkstergeest "hoch liber alIen Zerstreuungen der Geschlechter und des Glaubens" 64), but also in the "AufkHinmg". It remains unclear on quite a few points 65. As far as the different phases of the epistemological process is concerned, Averroes reputes Avicenna's innovation: the vis estimativa, as being unaristotelian, and returns to the traditional three levels: senses, imagination and cognition. As far as the actual abstraction process is concerned, one can distinguish the following elements with Avicenna. 1. The intelligible fonns (intentiones in the Latin translation) are present in aptitude and in imaginative capacity, that is, in the sensory images which are present there; 2. The fonns are actualised by the working of the Active Intellect (the lowest celestial sphere), that works in analogy to light ; 3. The intelligible fonns-in-act are "received" by the "possible" or the "material intellecf', which thereby changes into intellect-in-act, also called: habitual or acquired intellect: the. perfect form ofwhich - when all scientific knowledge that can be acquired, has been acquired -is called speculative intellect. 4. According to the Aristotelian principle that the epistemological process and knowing itselfcoincide, the state ofintellect-in-act implies - certainly as speculative intellect - the conjunction with the Active Intellect. 64 Cited by Ernst Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, (1953), in Suhrkamp, Gesamtausgabe, 7, p. -

Critical Theory of Herbert Marcuse: an Inquiry Into the Possibility of Human Happiness

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness Michael W. Dahlem The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahlem, Michael W., "Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5620. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5620 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s, Any further reprinting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library U n iv e rs ity o f Montana Date :_____1. 9 g jS.__ THE CRITICAL THEORY OF HERBERT MARCUSE: AN INQUIRY INTO THE POSSIBILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS By Michael W. Dahlem B.A. Iowa State University, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Date UMI Number: EP41084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Collisions with Hegel in Bertolt Brecht's Early Materialism DISSERTATIO

“Und das Geistige, das sehen Sie, das ist nichts.” Collisions with Hegel in Bertolt Brecht’s Early Materialism DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jesse C. Wood, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2012 Committee Members: John Davidson, Advisor Bernd Fischer Bernhard Malkmus Copyright by Jesse C. Wood 2012 Abstract Bertolt Brecht began an intense engagement with Marxism in 1928 that would permanently shape his own thought and creative production. Brecht himself maintained that important aspects resonating with Marxist theory had been central, if unwittingly so, to his earlier, pre-1928 works. A careful analysis of his early plays, poetry, prose, essays, and journal entries indeed reveals a unique form of materialism that entails essential components of the dialectical materialism he would later develop through his understanding of Marx; it also invites a similar retroactive application of other ideas that Brecht would only encounter in later readings, namely those of the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Initially a direct result of and component of his discovery of Marx, Brecht’s study of Hegel would last throughout the rest of his career, and the influence of Hegel has been explicitly traced in a number Brecht’s post-1928 works. While scholars have discovered proto-Marxist traces in his early work, the possibilities of the young Brecht’s affinities with the idealist philosopher have not been explored. Although ultimately an opposition between the idealist Hegel and the young Bürgerschreck Brecht is to be expected, one finds a surprising number of instances where the two men share an unlikely commonality of imagery. -

POL 478Y (POL2019Y5Y L0101) (Autumn 2016) MORAL REASON

POL 478Y (POL2019Y5Y L0101) (Autumn 2016) MORAL REASON AND ECONOMIC HISTORY Professor R.B. Day 229 Kaneff Centre (905) 828-5203 Office Hours: Thursday 3-5 email: [email protected] Course website: www.richardbday.com SECTION I: POLITICAL ECONOMY AND ETHICAL LIFE 1) 6 September – Course Outline and Grading 2) 7 September – Plato and Aristotle: Justice and Economy, the Ethical Whole and the Parts *K. Polanyi, “Aristotle Discovers the Economy” in G. Dalton (ed), Primitive, Archaic and Modern Economies: Essays of Karl Polanyi, ch. 5; also in Polanyi, Arensberg & Pearson (eds), Trade and Market in the Early Empires, pp. 64-94 Aristotle, The Politics Plato, The Republic J.J. Spengler, Origins of Economic Thought and Justice, ch. 5 E. Barker, Political Thought of Plato and Aristotle, chs. 3-4, 6-9 J. Barnes (ed), Cambridge Companion to Aristotle, chs. 7-8 S. Meikle, Aristotle’s Economic Thought 3) 13 September – Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin: “Embedded Consciousness,” Spiritual Community & the “Spirit of Capitalism” *Polanyi, “Obsolete Market Mentality,” in Dalton (ed), Primitive, Archaic and Modern Economies *Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism K. Samuelsson, Religion and Economic Action P.E. Sigmund (ed), St. Thomas Aquinas on Politics and Ethics R.H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism E.L. Fortin, "St. Thomas Aquinas" and “St. Augustine” in L. Strauss & J. Cropsey (eds), History of Political Philosophy A, Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism: The Stone Foundation Lectures Andre Bieler, Calvin’s Economic and Social Thought 4) 14 September – Adam Smith: Individual Moral Judgment and Macro-Economic Growth *J. Cropsey, “Adam Smith,” in L. -

Theory, Totality, Critique: the Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 16 Issue 1 Special Issue on Contemporary Spanish Article 11 Poetry: 1939-1990 1-1-1992 Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Goldstein, Philip (1992) "Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 11. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2334-4415.1297 This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Abstract Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity by Douglas Kellner. Keywords Frankfurt School, WWII, Critical Theory Marxism and Modernity, Post-modernism, society, theory, socio- historical perspective, Marxism, Marxist rhetoric, communism, communistic parties, totalization, totalizing approach This review essay is available in Studies in 20th Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol16/iss1/11 Goldstein: Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Cr Review Essay Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Douglas Kellner, Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity. -

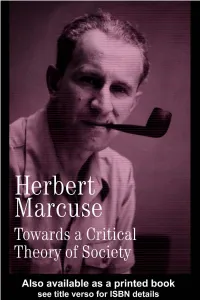

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical -

Towards an Understanding of Max Horkheimer Towards an Understanding

TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF MAX HORKHEIMER TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF MAX HORKHEIMER By JOHN MARSHALL, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by John Marshall, April 1999 MASTER OF ARTS (1999) McMaster University (Philosophy) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Towards an Understanding of Max Horkheimer. AUTHOR: John Marshall, B.A. (University of Regina) SUPERVISOR: Professor Catherine Beattie NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 97. li Abstract Due in large part to the writings of Jurgen Habermas, the philosophy of Max Horkheimer has recently undergone a re-examination. Although numerous thinkers have partaken in this re-examination, much of the discussion has occurred within a framework of debate established by Habermas' narrative of Horkheimer's philosophy. This thesis seeks to broaden that framework through a thorough, critical examination of Habermas' accounts. In chapter one, I survey Habermas' narrative centering on his treatment of the pivotal years in the 1940s. In chapter two, I expand on these years and argue that in contrast to Habermas' assertion that Horkheimer commits a performative contradiction, he instead engages in a logically consistent form of critique. In chapter three I discuss the later writings of Horkheimer and argue that the conception of philosophy contained therein is a continuation of his philosophy of the 1940s. Finally, in the conclusion I point to the implications which the above should have for Horkheimerian studies in general. iii Acknowledgements In a project such as this, a debt of gratitude is owed to a number of individuals without whose patient help, it could never have been completed. -

1 Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse, Volume 3: the New Left

Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse, Volume 3: The New Left and the 1960s Edited by Douglas Kellner Introduction by Douglas Kellner Preface by Angela Davis I. Interventions: “The Inner Logic of American Policy in Vietnam," 1967; “Reflections on the French Revolution,” 1968; “Student Protest is Nonviolent Next to the Society Itself”; “Charles Reich as Revolutionary Ostrich,” 1970; “Dear Angela,” 1971; “Reflections on Calley,” 1971; and “Marcuse: Israel strong enough to concede,” 1971 II. “The Problem of Violence and the Radical Opposition” III. "Liberation from the Affluent Society" IV. "Democracy Has/Hasn't a Future...A present" V. "Marcuse Defines His New Left Line" VI. Testimonies: Herbert Marcuse on Czechoslovakia and Vietnam; the University of California at San Diego Department of Philosophy on Herbert Marcuse; T.W. Adorno on Herbert Marcuse. VII. "On the New Left" VIII. “Mr. Harold Keen: Interview with Dr. Herbert Marcuse” IX. "USA: Questions of Organization and Revolutionary Subject: A Conversation with Hans-Magnus Enzensberger" X. "The Movement in an Era of Repression" XI. "A Conversation with Herbert Marcuse: Bill Moyers" XII. “Marxism and Feminism” XIII. 1970s Interventions: "Ecology and Revolution”; “Murder is Not a Political Weapon”; “Thoughts on Judaism, Israel, etc…” XIV. "Failure of the New Left?" Afterword by George Katsiaficas, “Marcuse as an Activist: Reminiscences of his Theory and Practice“ 1 Radical Politics, Marcuse, and the New Left Douglas Kellner In the 1960s Herbert Marcuse was promoted to the unlikely role of