Language Policies and Early Bilingual Education in Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments Received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2015-046 Outcome

Comments received for ISO 639-3 Change Request 2015-046 Outcome: Accepted after appeal Effective date: May 27, 2016 SIL International ISO 639-3 Registration Authority 7500 W. Camp Wisdom Rd., Dallas, TX 75236 PHONE: (972) 708-7400 FAX: (972) 708-7380 (GMT-6) E-MAIL: [email protected] INTERNET: http://www.sil.org/iso639-3/ Registration Authority decision on Change Request no. 2015-046: to create the code element [ovd] Ӧvdalian . The request to create the code [ovd] Ӧvdalian has been reevaluated, based on additional information from the original requesters and extensive discussion from outside parties on the IETF list. The additional information has strengthened the case and changed the decision of the Registration Authority to accept the code request. In particular, the long bibliography submitted shows that Ӧvdalian has undergone significant language development, and now has close to 50 publications. In addition, it has been studied extensively, and the academic works should have a distinct code to distinguish them from publications on Swedish. One revision being added by the Registration Authority is the added English name “Elfdalian” which was used in most of the extensive discussion on the IETF list. Michael Everson [email protected] May 4, 2016 This is an appeal by the group responsible for the IETF language subtags to the ISO 639 RA to reconsider and revert their earlier decision and to assign an ISO 639-3 language code to Elfdalian. The undersigned members of the group responsible for the IETF language subtag are concerned about the rejection of the Elfdalian language. There is no doubt that its linguistic features are unique in the continuum of North Germanic languages. -

THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE Sharingsweden.Se PHOTO: CECILIA LARSSON LANTZ/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN / THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE sharingsweden.se PHOTO: CECILIA LARSSON LANTZ/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE PHOTO: THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE Sweden is a multilingual country. However, Swedish is and has always been the majority language and the country’s main language. Here, Catharina Grünbaum paints a picture of the language from Viking times to the present day: its development, its peculiarities and its status. The national language of Sweden is Despite the dominant status of Swedish, Swedish and related languages Swedish. It is the mother tongue of Sweden is not a monolingual country. Swedish is a Nordic language, a Ger- approximately 8 million of the country’s The Sami in the north have always been manic branch of the Indo-European total population of almost 10 million. a domestic minority, and the country language tree. Danish and Norwegian Swedish is also spoken by around has had a Finnish-speaking population are its siblings, while the other Nordic 300,000 Finland Swedes, 25,000 of ever since the Middle Ages. Finnish languages, Icelandic and Faroese, are whom live on the Swedish-speaking and Meänkieli (a Finnish dialect spoken more like half-siblings that have pre- Åland islands. in the Torne river valley in northern served more of their original features. Swedish is one of the two national Sweden), spoken by a total of approxi- Using this approach, English and languages of Finland, along with Finnish, mately 250,000 people in Sweden, German are almost cousins. for historical reasons. Finland was part and Sami all have legal status as The relationship with other Indo- of Sweden until 1809. -

Authentic Language

! " " #$% " $&'( ')*&& + + ,'-* # . / 0 1 *# $& " * # " " " * 2 *3 " 4 *# 4 55 5 * " " * *6 " " 77 .'%%)8'9:&0 * 7 4 "; 7 * *6 *# 2 .* * 0* " *6 1 " " *6 *# " *3 " *# " " *# 2 " " *! "; 4* $&'( <==* "* = >?<"< <<'-:@-$ 6 A9(%9'(@-99-@( 6 A9(%9'(@-99-(- 6A'-&&:9$' ! '&@9' Authentic Language Övdalsk, metapragmatic exchange and the margins of Sweden’s linguistic market David Karlander Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Doctoral dissertation, 2017 Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Copyright © David Budyński Karlander Printed and bound by Universitetsservice AB, Stockholm Correspondence: SE 106 91 Stockholm www.biling.su.se ISBN 978-91-7649-946-7 ISSN 1400-5921 Acknowledgements It would not have been possible to complete this work without the support and encouragement from a number of people. I owe them all my humble thanks. -

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue?

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community NORD: 2012:008 ISBN: 978-92-893-2404-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/Nord2012-008 Author: Karin Arvidsson Editor: Jesper Schou-Knudsen Research and editing: Arvidsson Kultur & Kommunikation AB Translation: Leslie Walke (Translation of Bodil Aurstad’s article by Anne-Margaret Bressendorff) Photography: Johannes Jansson (Photo of Fredrik Lindström by Magnus Fröderberg) Design: Mar Mar Co. Print: Scanprint A/S, Viby Edition of 1000 Printed in Denmark Nordic Council Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K DK-1061 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 www.norden.org The Nordic Co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Preface Languages in the Nordic Region 13 Fredrik Lindström Language researcher, comedian and and presenter on Swedish television. -

Perspectives on English Language Education in Sweden

四天王寺大学紀要 第 52 号(2011 年 9 月) Perspectives on English Language Education in Sweden Koji IGAWA & Shigekazu YAGI [Abstract] This is a literature review on current situations of English language education at compulsory schools in Sweden. By examining a variety of literature, the study is to investigate the 9-year English education system in Sweden’s compulsory primary schools (ages 7 - 16) as well as to explore the issue from the following four (4) diverse perspectives that are supposed to impact English education in Sweden: (1) Linguistic affinities between L1 (First Language: Swedish) and TL (Target Language: English), (2) Swedish culture’s historical compatibilities with and current assimilation by Anglo-American culture, (3) Language policies motivated by Sweden becoming a member of the European Union (EU) in 1995, and (4) EU’s recommended language teaching approach of “Content and Language Integrated Learning” (CLIL). A brief set of implications for English language education in Japan are gleaned from the results of this study. [Keywords] English Education in Sweden, EU’s Language Policy, CLIL I. Introduction The harmonious co-existence of many languages in Europe is a powerful symbol of the European Union's aspiration to be united in diversity, one of the cornerstones of the European project. Languages define personal identities, but are also part of a shared inheritance. They can serve as a bridge to other people and open access to other countries and cultures, promoting mutual understanding. A successful multilingualism policy can strengthen life chances of citizens: it may increase their employability, facilitate access to services and rights and contribute to solidarity through enhanced intercultural dialogue and social cohesion. -

English in Scandinavia: Monster Or Mate? Sweden As a Case Study 1

1 English in Scandinavia: Monster or Mate? Sweden as a Case Study Catrin Norrby Introduction When Swedish Crown Princess Victoria and Prince Daniel recently became parents, the prince explained his feelings at a press conference, hours after their daughter was born, with the following words (cited from Svenska Dagbladet, 23 February 2012): Mina känslor är lite all over the place. När jag gick från rummet så låg den lilla prinsessan på sin moders bröst och såg ut att ha det väldigt mysigt [My feelings are a bit all over the place. When I left the room the little princess was lying on her mother’s breast and seemed to be very cosy] The use of English catchphrases and idioms in an otherwise Swedish lan- guage frame is not unusual and it is no exaggeration to say that English plays a significant role in contemporary Scandinavia. The following areas of use at least can be distinguished: (1) English taught as a school subject; (2) English used as a lingua franca; (3) English in certain domains; (4) English as an act of identity; and (5) English in the linguistic landscape. The term ‘Scandinavia’ is used in this chapter as shorthand for Denmark, Norway and Sweden (where Scandinavian languages are spoken) as well as for Finland (which is part of the Scandinavian peninsula together with Sweden and Norway). English is taught as a mandatory subject in schools throughout Scandinavia, usually from Grade 3 or 4, meaning that school leavers normally have 9–10 years of English teaching. In recent years there has been an increase of CLIL (content and language integrated learning), where content subjects are taught in English (see, for example, Washburn, 1997). -

Swedishpod101 Swedishpod101

SwedishPod101 Learn Swedish with FREE Podcasts All About S1 History of The Swedish Language and Top 5 Reasons to Learn Swedish 1 Grammar Points 2 SwedishPod101 Learn Swedish with FREE Podcasts Grammar Points The Focus of This Lesson is the History of Swedish. I. Linguistics The Swedish language has over ten million native speakers and it is spoken in Sweden as well as in Finland. Swedish is closely related to other Scandinavian languages, and a person who speaks and understands Swedish will also without great difficulty understand Norwegian and Danish. Swedish is a North Germanic language, descended from Old Norse, the language spoken by the Vikings. Swedish is the largest language amongst all North Germanic languages. The history of Swedish begins in the 9th century, when Old Norse started to divide into Old West Norse and Old East Norse. In the 12th century these two groups began to create what we now call Norwegian and Icelandic, and Swedish and Danish. Today they are four separate languages, but it is easy to see the similarities among them. In one way the Scandinavian languages are mere different dialects derived from the same languages. Because of wars and rivalry between Sweden and Denmark, the languages parted and created their own dictionaries and formal written concepts. Also, Norway and Finland have once belonged to 2 Sweden, another reason that the languages seem to be somewhat shared. In addition, there are subordinate dialects within the Swedish language, especially along the western parts close to Norway and the southern parts close to Denmark. These dialects use vocabulary in different ways, borrow words from the neighbouring countries, and hold on to an older way of speaking. -

978-1-926846-94-1.Pdf

This is a reproduction of a book from the McGill University Library collection. Title: Travels through Denmark, Sweden, Austria, and part of Italy in 1798 & 1799 Author: Küttner, Carl Gottlob, 1755-1805 Publisher, year: London : Printed for Richard Phillips, 1805 The pages were digitized as they were. The original book may have contained pages with poor print. Marks, notations, and other marginalia present in the original volume may also appear. For wider or heavier books, a slight curvature to the text on the inside of pages may be noticeable. ISBN of reproduction: 978-1-926846-94-1 This reproduction is intended for personal use only, and may not be reproduced, re-published, or re-distributed commercially. For further information on permission regarding the use of this reproduction contact McGill University Library. McGill University Library www.mcgill.ca/library TRAVELS THROUGH DENMARK, SAVEDEN, AUSTRIA, AND PART OF ITALY, IN 1798 # 1799, BY CHARLES GOTTLOB KUTTNER TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN. LONDON: PRINTED FOR RICHARD PHILLIPS, 71, ST. PAUL'S CHUUCK YARD, By Barnard # Sultzer, Water Lane, Fleet Street, 1805. ADVERTISEMENT OF THE TRANSLATOR. 1 HE Writer of the following Pages is a literary Character of considerable eminence in Germany, and not wholly unknown in Eng land, with which a long visit has rendered him intimately acquainted. His observations are obviously not the result of a superficial mind. A residence in different Countries has fur nished him with an opportunity of seeing objects in various points of view, and has enabled him to draw more accurate conclu sions from those which fall under his observ ation. -

NOT YET-Constructions in the Swedish Skellefteå Dialect

NOT YET-Constructions in the Swedish Skellefteå Dialect Jill Zachrisson Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General Linguistics Spring term 2020 Supervisor: Ljuba Veselinova Examiner: Mats Wirén Swedish Title: Inte än-konstruktioner i Skelleftemålet Project affiliation: Expectations shaping grammar: searching for the link between tense-aspect and negation, a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (Grant nr 2016-01045) NOT YET-Constructions in the Swedish Skellefteå Dialect Abstract Expressions such as not yet, already, still and no longer belong to a category called Phasal Polarity (Phasal Polarity), and express phase, polarity and speaker expectations. In European languages, these often appear as phasal adverbs. However, in the Skellefteå dialect, spoken in northern Sweden, another type of construction is also used to express not yet. The construction consists of the auxiliary hɶ ‘have’ together with the supine form of the lexical verb prefixed by the negative prefix o-, for example I hɶ oskrive breve ‘I haven’t written the letter yet’. I will refer to this construction as the o-construction. Constructions meaning not yet have lately been referred to as nondum (from Latin nondum 'not yet') (Veselinova & Devos, forthcoming) and appear to be widely used in grammaticalized forms in, for example, Austronesian- and Bantu languages. The o-construction in the Skellefteå dialect is only mentioned but has no detailed documentation in existing descriptions. The aim of this study is to collect data and analyze the use of this construction. Data were collected through interaction with speakers of the Skellefteå dialect, using questionnaires and direct elicitation. -

Swedish As a Second Language

Appendix Swedish as a second language The subject of Swedish as a second language gives students with a mother tongue other than Swedish the opportunity to develop their communicative language skills. A rich language is a prerequisite for acquiring new knowledge, passing further studies and taking an active part in social and working life. It is also through language that we express our personality and interact with other people in various situations. The subject helps students to enhance their multilingualism and confidence in their own language skills, while at the same time gaining greater respect for the languages of others and the way in which other people express themselves. The purpose of the subject The purpose of teaching the subject Swedish as a second language is that students should develop skills in and knowledge of the Swedish language. Students should also be given the opportunity to reflect on their own multilingualism and their ability to master and develop a functional and rich second language in Swedish society. In the teaching, students should be given plenty of opportunities to meet, produce and analyse verbal and written language. Fiction, texts of various kinds, film and other media should be used as a source of insight into other people's experiences, thoughts and perceptions and to give students an opportunity to develop a varied and nuanced language. The content should be chosen so that the students' past experiences and knowledge are taken into account. The teaching should also help students develop knowledge about how to search for, compile and critically review information from different sources. -

Can a True Finn Speak Swedish? the Swedish Language in the Finns Party Discourse

Journal of Autonomy and Security Studies Vol. 3 Issue 1 Can a True Finn Speak Swedish? The Swedish Language in the Finns Party Discourse Hasan Akintug ´ Journal of Autonomy and Security Studies, 3(1) 2019, 28–39 URL: http://jass.ax/volume-3-issue-1-Akintug/ Abstract This paper aims to analyse the rhetorical utilisation of Swedish language in the discourse of the Finns Party. This contribution will provide an overview of the history of Swedish language in Finland and will attempt to analyse the relationship between the two language groups. This contribution will analyse the rhetorical uses of Swedish language within the discourse of the Finns Party with the intention to highlight the consistently negative portrayals of Swedish language and its status. It will be argued that the historical experience of the inequality of status between the Swedish and Finnish languages have been politicised by the Finns Party as a part of its ethno-nationalist and populist conceptualisation of the Finnish identity. Keywords Rhetoric, Nationalism, Populism, Identity, Discourse About the author: Hasan Akintug holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science and Public Administration from Hacettepe University and is currently a student at the University of Helsinki, European and Nordic Studies Master’s program. He has worked as a research assistant at IKME Sociopolitical Studies Institute, the Åland Islands Peace Institute and the Centre for European Studies at the University of Helsinki. His main research interests include minorities and autonomous regions. 28 Journal of Autonomy and Security Studies Vol. 3 Issue 1 1. Introduction The Swedish language has been one of the eternal issues of Finnish politics. -

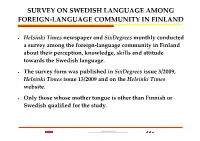

Survey on Swedish Language Among Foreign-Language Community in Finland

SURVEY ON SWEDISH LANGUAGE AMONG FOREIGN-LANGUAGE COMMUNITY IN FINLAND ● Helsinki Times newspaper and SixDegrees monthly conducted a survey among the foreign-language community in Finland about their perception, knowledge, skills and attitude towards the Swedish language. ● The survey form was published in SixDegrees issue 3/2009, Helsinki Times issue 13/2009 and on the Helsinki Times website. ● Only those whose mother tongue is other than Finnish or Swedish qualified for the study. RESPONDENTS ● A total of 510 people answered the survey. ● 61% of the respondents are men and 39% women. ● The respondents represent 79 nationalities and 71 languages as their mother tongue. ● 90% of the respondents speak at least one language fluently in addition to their own mother tongue. BIGGEST GROUPS ● The biggest nationality groups: Germany 7.8%, the UK 6.7%, the US 6.1%, China 6.1%, India 5.7%, Nepal 4.5% and Russia 4.5%. ● The biggest mother-tongue language groups: English 22.4%, German 8.8%, Chinese 5.9%, Spanish 5.1%, Russian 4.9%, Nepali 4.3% and French 4.1%. RESPONDENTS' NATIONALITIES ● Australia, Austria ● Kenya, Kuwait ● Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, ● Latvia, Lithuania Bulgaria ● Malaysia, Mexico, Moldova, Mongolia, ● Cameroon, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Morocco Congo, Czech Republic ● Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, ● Denmark ● Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, ● Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia Puerto Rico ● Finland, France, ● Romania, Russia, Rwanda ● Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, ● Serbia, Slovakia,