Reconstructing the Image of the Ideal City in Renaissance Painting and Theatre: Its Influence in Specific Urban Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Reviews Summer 2020

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Marinazzo, A, et al. 2020. Reviews Summer 2020. Architectural Histories, 8(1): 11, pp. 1–13. DOI: +LVWRULHV https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.525 REVIEW Reviews Summer 2020 Adriano Marinazzo, Stefaan Vervoort, Matthew Allen, Gregorio Astengo and Julia Smyth-Pinney Marinazzo, A. A Review of William E. Wallace, Michelangelo, God’s Architect: The Story of His Final Years and Greatest Masterpiece. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019. Vervoort, S. A Review of Matthew Mindrup, The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar and the Muse. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2019. Allen, M. A Review of Joseph Bedford, ed., Is There an Object-Oriented Architecture? Engaging Graham Harman. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. Astengo, G. A Review of Vaughan Hart, Christopher Wren: In Search of Eastern Antiquity. London: Yale University Press, 2020. Smyth-Pinney, J. A Review of Maria Beltramini and Cristina Conti, eds., Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane: Architettura e decorazione da Leone X a Paolo III. Milan: Officina libraria, 2018. Becoming the Architect of St. Peter’s: production of painting, sculpture and architecture and Michelangelo as a Designer, Builder and his ‘genius as entrepreneur’ (Wallace 1994). With this new Entrepreneur research, in his eighth book on the artist, Wallace mas- terfully synthesizes what aging meant for a genius like Adriano Marinazzo Michelangelo, shedding light on his incredible ability, Muscarelle Museum of Art at William and Mary, US despite (or thanks to) his old age, to deal with an intri- [email protected] cate web of relationships, intrigues, power struggles and monumental egos. -

Ah Timeline Images ARCHITECTURE

8. STONEHENGE 12. WHITE TEMPLE & ZIGGURAT, URUK c. 2,500 - c. 3,500 - 1,600 BCE 3,000 BCE monolithic Sumerian sandstone Temple henge present day present day Wiltshire, UK Warka, Iraq SET 1: GLOBAL PREHISTORY 30,000 - 500 BCE SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE 17. GREAT PYRAMIDS OF GIZA 20. TEMPLE OF AMUN-RE & HYPOSTYLE HALL c. 2,550 - c. 1,250 BCE 2,490 BCE cut sandstone cut limestone / and brick Khufu Egyptian Khafre / Sphinx Menkaure temple present day Karnak, near Cairo, Egypt Luxor, Egypt SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE 21. MORTUARY TEMPLE OF HATSHEPSUT 26. ATHENIAN AGORA c. 1,490 - 600 BCE - 1,460 BCE 150 CE slate eye civic center, makeup ancient Athens palette present day Egyptian Athens, Museum, Cairo Greece SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE 30. AUDIENCE HALL OF DARIUS & XERXES 31. TEMPLE OF MINERVA / SCULPTURE OF APOLLO c. 520 - 465 c. 510 - 500 BCE BCE Limestone Wood, mud Persian brick, tufa Apadana temple / terra SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE cotta sculpture Persepolis, Iran Veii, near Rome SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE 35. ACROPOLIS ATHENS, GREECE 38. GREAT ALTAR OF ZEUS & ATHENA AT PERGAMON c. 447 - 424 c. 175 BCE BCE Hellenistic Iktinos & Greek Kallikrates, marble altar & Marble temple complex sculpture Present day Antiquities Athens, Greece Museum , Berlin SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE SET 2: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN 3,500 - 300 BCE 39. -

Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown. Architecture As Signs and Systems

Architecture as Signs and Systems For a Mannerist TIme Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS· CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS· LONDON, ENGLAND· 2004 Art & Arch e'J' ,) re Library RV: Washington u:'li \/(H'si ty Campus Box 1·,):51 One Brookin18 Dr. st. Lg\li,s, !.:0 &:n:W-4S99 DSB: RV, DSB: Copyright e 2004 by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown All rights reserved Printed in Italy Book Design by Peter Holm, Sterling Hill Productions Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Venturi, Robert. Architecture as and systems: for a mannerist time I Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. p. em. - (The William E. Massey, Sr. lectures in the history of American civilization) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-01571-1 (alk. paper) 1. Symbolism in architecture. 2. Communication in architectural design. I. Scott Brown, Denise, 1931- II. Title. ill. Series. NA2500.V45 2004 nO'.I-dc22 200404{)313 ttext," for show his l them in lied "that le most of 'espitemy to be an me of our 19 studies, mth these Architecture as Sign rather than Space ecause if I New Mannerism rather than Old Expressionism 1geswon't ROBERT VENTURI ,the com :tronger ::ople who . work and lity to the _~.'n.•. ~~~,'~'"'.".'."_~ ____'_''''"'«'''.'''''',_",_.""",~",-,-" ".,-=--_""~ __ , ..... """'_.~~"',.._'''''_..._,,__ *' ...,',.,..,..... __ ,u~.,_~ ... mghai, China. 2003 -4 -and for Shanghai, the mul A New Mannerism, for Architecture as Sign . today, and tomorrow! This of LED media, juxtaposing nbolic, and graphic images at So here is complexity and contradiction as mannerism, or mannerism as ing. -

Humanism and Spanish Literary Patronage at the Roman Curia: the Role of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino López De Carvajal (1456–1523)

2017 IV Humanism and Spanish Literary Patronage at the Roman Curia: The Role of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino López de Carvajal (1456–1523) Marta Albalá Pelegrín Article: Humanism and Spanish Literary Patronage at the Roman Curia: The Role of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino López de Carvajal (1456-1523) Humanism and Spanish Literary Patronage at the Roman Curia: The Role of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino López de Carvajal (1456-1523)1 Marta Albalá Pelegrín Abstract: This article aims to analyze the role of Bernardino López de Carvajal (1456 Plasencia-1523 Rome) as a literary patron, namely his contributions to humanism in Rome and to Spanish letters, in the period that has been loosely identified as Spanish Rome. Carvajal held the dignities of orator continuus of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, titular cardinal of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, and Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, and was even elected antipope with the name of Martin VI in the Conciliabulum of Pisa (1511) against Julius II. He belonged to the avant-garde of humanists devoted to creating a body of Neo-Latin and Spanish literature that would both foster the Spanish presence at Rome and leave a mark on the Spanish literary canon. He sponsored a considerable body of works that celebrated the deeds of the Catholic Kings and those of the Great Captain, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba. He also commissioned literary translations, and was involved in the production of theatrical pieces, such as those of Bartolomé Torres Naharro. Key Words: Benardino López de Carvajal; Literary Patronage; Catholic Kings; Erasmus; Bartolomé Torres Naharro; Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba. -

Borromini and the Cultural Context of Kepler's Harmonices Mundi

Borromini and the Dr Valerie Shrimplin cultural context of [email protected] Kepler’sHarmonices om Mundi • • • • Francesco Borromini, S Carlo alle Quattro Fontane Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk II, p. 64 Facsimile, Carnegie-Mellon University Francesco Borromini, S Ivo alla Sapienza Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk IV, p. 137 • Vitruvius • Scriptures – cosmology and The Genesis, Isaiah, Psalms) cosmological • Early Christian - dome of heaven view of the • Byzantine - domed architecture universe and • Renaissance revival – religious art/architecture symbolism of centrally planned churches • Baroque (17th century) non-circular domes as related to Kepler’s views* *INSAP II, Malta 1999 Cosmas Indicopleustes, Universe 6th cent Last Judgment 6th century (VatGr699) Celestial domes Monastery at Daphne (Δάφνη) 11th century S Sophia, Constantinople (built 532-37) ‘hanging architecture’ Galla Placidia, 425 St Mark’s Venice, late 11th century Evidence of Michelangelo interests in Art and Cosmology (Last Judgment); Music/proportion and Mathematics Giacomo Vignola (1507-73) St Andrea in Via Flaminia 1550-1553 Church of San Giacomo in Augusta, in Rome, Italy, completed by Carlo Maderno 1600 [painting is 19th century] Sant'Anna dei Palafrenieri, 1620’s (Borromini with Maderno) Leonardo da Vinci, Notebooks (318r Codex Atlanticus c 1510) Amboise Bachot, 1598 Following p. 52 Astronomia Nova Link between architecture and cosmology (as above) Ovals used as standard ellipse approximation Significant change/increase Revival of neoplatonic terms, geometrical bases in early 17th (ellipse, oval, equilateral triangle) century Fundamental in Harmonices Mundi where orbit of every planet is ellipse with sun at one of foci Borromini combined practical skills with scientific learning and culture • Formative years in Milan (stonemason) • ‘Artistic anarchist’ – innovation and disorder. -

48. Catacomb of Priscilla. Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. C. 200–400 C.E

48. Catacomb of Priscilla. Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 200–400 C.E. Excavated tufa and fresco. (3 images) Orant fresco © Araldo de Luca/Corbis Greek Chapel © Scala/Art Resource, NY Good Shepherd fresco © Scala/Art Resource, NY 49. Santa Sabina. Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 422–432 C.E. Brick and stone, wooden roof. (3 images) Santa Sabina Santa Sabina © Holly Hayes/Art History Images © Scala/Art Resource, NY Santa Sabina plan 50. Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well and Jacob Wrestling the Angel, from the Vienna Genesis. Early Byzantine Europe. Early sixth century C.E. Illuminated manuscript (tempera, gold, and silver on purple vellum). (2 images) Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well Jacob Wrestling the Angel © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Gr. 31, fol. 7r © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Gr. 31, fol. 12r 51. San Vitale. Ravenna, Italy. Early Byzantine Europe. c. 526–547 C.E. Brick, marble, and stone veneer; mosaic. (5 images) San Vitale San Vitale © Gérard Degeorge/The Bridgeman Art Library © Canali Photobank, Milan, Italy San Vitale, continued Justinian panel Theodora panel © Cameraphoto Arte, Venice/Art Resource, NY © Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library San Vitale plan 52. Hagia Sophia. Constantinople (Istanbul). Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. 532–537 C.E. Brick and ceramic elements with stone and mosaic veneer. (3 images) Hagia Sophia © Yann Arthus-Bertrand/Corbis Hagia Sophia © De Agostini Picture Library/G. Dagli Orti/The Bridgeman Art Library Hagia Sophia plan 53. Merovingian looped fibulae. Early 54. Virgin (Theotokos) and Child medieval Europe. Mid-sixth century C.E. between Saints Theodore and George. Silver gilt worked in ftligree, with inlays Early Byzantine Europe. -

Francesco Borromini Church of San Carlo Alle Quattro Fontane, 1635-1641/1665-1667

Art Analysis Francesco Borromini Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1635-1641/1665-1667 Figg. 1, 2, 3 Francesco Borromini, Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 1635-1641. Rome. View of the interior hall (left), of the dome (right) and the plan (bottom). The Patronage of a Minor Order from two equilateral triangles that share a common base, cor- In 1634 the Order of the Spanish Secular Trinitarians com- responding to a transversal axis. missioned Borromini to design San Carlo alle Quattro Fon- As opposed to other similar plans, such as Bernini’s Saint tane. Between 1635 and 1641 the group of buildings – the Peter’s Square and Sant’Andrea in Quirinale, this church is cloister, refectory, dormitory and church – was constructed laid out in a longitudinal way; this arrangement generates while the façade was only completed some thirty years later a sensation of compression along the diagonal directives. (1665-1667). Therefore the complex sums up all the stylistic In fact the inside of the church is dominated by a sense of experiences that Borromini was experimenting with over that accentuated spatial dynamism; as the churchgoer moves long period, forming something like a three dimensional an- towards the altar, the strong undulated rhythm of the walls thology of Baroque vocabulary. suggests a feeling of the space’s contraction and expansion. After the architect’s death his nephew Bernardo completed The predominance of white walls accentuates this effect. the upper story and the decoration. The entire interior is faced in white stucco, inter- The Design: the Cloister and the Inside of the Church rupted only by slightly Borromini had to deal with the limits imposed by the available gilded grille-work in space which was confined and irregular; however he turned wrought iron, as well as by these conditions to his advantage by finding innovative and, the red Trinitarian cross, in a certain sense, revolutionary solutions. -

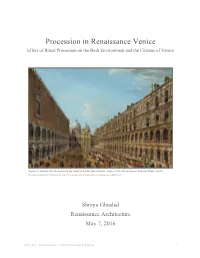

Procession in Renaissance Venice Effect of Ritual Procession on the Built Environment and the Citizens of Venice

Procession in Renaissance Venice Effect of Ritual Procession on the Built Environment and the Citizens of Venice Figure 1 | Antonio Joli, Procession in the Courtyard of the Ducal Palace, Venice, 1742. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art Reproduced from National Gallery of Art, http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/art-object-page.32586.html Shreya Ghoshal Renaissance Architecture May 7, 2016 EXCERPT: RENAISSANCE ARCH RESEARCH PAPER 1 Excerpt from Procession in Renaissance Venice For Venetians, the miraculous rediscovery of Saint Mark’s body brought not only the reestablishment of a bond between the city and the Saint, but also a bond between the city’s residents, both by way of ritual procession.1 After his body’s recovery from Alexandria in 828 AD, Saint Mark’s influence on Venice became evident in the renaming of sacred and political spaces and rising participation in ritual processions by all citizens.2 Venetian society embraced Saint Mark as a cause for a fresh start, especially during the Renaissance period; a new style of architecture was established to better suit the extravagance of ritual processions celebrating the Saint. Saint Mark soon displaced all other saints as Venice’s symbol of independence and unity. Figure 2 | Detailed Map of Venice Reproduced from TourVideos, http://www.lahistoriaconmapas.com/atlas/italy-map/italy-map-venice.htm 1 Edward Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), 87. 2 Muir, Civic Ritual, 80-81. EXCERPT: RENAISSANCE ARCH RESEARCH PAPER 2 The Renaissance period in Venice, lasting through the Quattrocento and Cinquecento, was significant because of the city’s maintenance of civic peace; this was achieved in large part by the rise in number and importance of processional routes by the Doges, the elected leaders of the Republic.3 Venice proved their commitment to these processions by creating a grander urban fabric. -

Timeline – Roman-Renn Foundling Hospital, Florence 1419 AD Pantheon, Rome 118 AD Parthenon, Athens 450 BC

700 600 500 Parthenon, Athens 450 BC 400 300 200 100 Timeline – roman-renn 0 100 Pantheon, Rome 118 AD 200 300 400 500 600 Roman Greek Egyptian Gothic 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 Foundling Hospital, Florence 1419 AD 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 Timeline – renn-rococo 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Roman Greek Egyptian Gothic 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 Early Renaissance 1500 High Late 1600 Baroque 1700 Rococo 1800 1900 2000 graph 1 kouros-archaic doric archaic rothko progression le corbusier-early le corbusier-early language exp language exp graph 2 evolution evolution evolution complexity dramatic arc early-late renn high modernism bauhaus unite d’habitation deconstruction Baroque modernism jumping the shark Denver Liebeskind Denver 1970 ponti pruitt-igo pruitt-igo plan voisson santa croce san lorenzo maggiore-mid neumann-late san chappelle 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 Timeline – roman-renn 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Roman Greek Egyptian Gothic 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 croce-lorenzo-compare florence duccio renaissance painting school of athens foundling 1419 foundling hospital detail palazzo medici plan palazzo medici Strozzi ruccelai palazzo vecchio pienza- naive pienza- wright-richardson-arch corner santa croce 1429-pazzi pazzi pazzi chapel pazzi Pazzi corner-interior Intr. Corner Detail -exterior 1444-michelozzo michelozzo 1459 picolomini, pienza-1459 1500 s.m. dla pace-bramante 1500- Cancelleria rome 1468 palazzo ducale, 1587 palazzo della sapienza-de la porte, rome coliseum 1515 palazzo farnese, rome 1526 Carlos V by machucha, alhambra carlos V alhambra 1526 san lorenzo facade san lorenzo/sm d fiore Alberti alberti alberti sm novella san lorenzo facade san lorezo façade san lorenzo facade san lorenzo facade michel-sketch san lorenzo facade san lorenzo facade san lorenzo facade san lorenzo facade basilica basilica basilica basilica basilica basilica basilica façade san lorenzo facade s miniato sm novella Palladio –double ped. -

{TEXTBOOK} Italy at Work : Her Renaissance in Design Today Pdf

ITALY AT WORK : HER RENAISSANCE IN DESIGN TODAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Meyric Reynold Rogers | 128 pages | 10 Feb 2010 | Nabu Press | 9781143311901 | English | Charleston SC, United States Italy at Work : Her Renaissance in Design Today PDF Book The broad appeal of the nude extended to the novel and personal ways Renaissance patrons sought to incorporate nude figures into the works of art they commissioned. Learning Objectives Name some distinguishing features of Italian Renaissance architecture, its major exponents, and important architectural concepts. Teatro Olimpico : Scaenae frons of the Teatro Olimpico. One primary emphasis of the Counter-Reformation was a mission to reach parts of the world that had been colonized as predominantly Catholic, and also try to reconvert areas, such as Sweden and England, that were at one time Catholic but had been Protestantized during the Reformation. The Renaissance has had a large impact on society in a multitude of ways. The Palazzo Farnese, one of the most important High Renaissance palaces in Rome , is a primary example of Renaissance Roman architecture. With its perfect proportions, harmony of parts, and direct references to ancient architecture, the Tempietto embodies the Renaissance. Working together across cultural and religious divides, they both become very rich, and the Ottomans became one of the most powerful political entities in the world. A popular explanation for the Italian Renaissance is the thesis that the primary impetus of the early Renaissance was the long-running series of wars between Florence and Milan, whereby the leading figures of Florence rallied the people by presenting the war as one between the free republic and a despotic monarchy.