Race, Rat Bites and Unfit Mothers: How Media Discourse Informs Welfare Legislation Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 21, 2014 Vol. 118 No. 47

VOL. 118 - NO. 47 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 21, 2014 $.35 A COPY Thanksgiving vs. Roseland and Massport Celebrate Opening of the Big Box Company PORTSIDE AT EAST PIER BUILDING 7 by Nicole Vellucci Ribbon-Cutting Held for Luxury Residential and Retail Complex in East Boston Thanksgiving, a Roseland, a subsidiary of day synonymous Mack-Cali Realty Corpora- with the word fam- tion (NYSE: CLI), in partner- ily in American cul- ship with the Massachusetts ture, has become Port Authority (Massport), more about the dol- hosted a ribbon-cutting for lar than together- the opening of Portside at ness. As a child, our East Pier Building 7, its flag- Thanksgiving ship luxury residential and preparations began retail complex located at 50 weeks prior to the Lewis Street in East Boston. main event with planning the menu, inviting family and Joined by Senator Anthony friends and endless trips to the grocery store. My father Petruccelli and State Rep. would post the dinner menu on our kitchen refrigerator Carlo Basile, Roseland and and everyone was asked to add their requests. Turkey day Massport celebrated the morning began with naming our bird (or birds since one completion of the initial thirty-pound turkey was not enough because you never building in East Boston’s first knew who would stop by) and preparation of all the deli- residential waterfront devel- Left to right: State Senator Anthony Petruccelli, cious accompaniments. Besides the wonderful aroma of this opment project in decades. Roseland President Marshall Tycher, City Councilor Sal feast filling our home, what I remember most is all the Portside at East Pier Build- LaMattina, State Rep Carlo Basile, BRA Director Brian Golden and Massport CEO Tom Glynn. -

(Pdf) Download

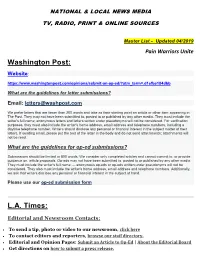

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Boston Druggists' Association

BOSTON DRUGGISTS’ ASSOCIATION SPEAKERS, 1966 to 2019 Date Speaker Title/Topic February 15, 1966 The Honorable John A. Volpe Governor of Massachusetts March 22, 1966 William H. Sullivan, Jr. President, Boston Patriots January 24, 1967 Richard E. McLaughlin Registry of Motor Vehicles March 21, 1967 Hal Goodnough New York Mets Baseball February 27, 1968 Richard M. Callahan “FDA in Boston” January 30, 1968 The Honorable Francis W. Sargeant “The Challenge of Tomorrow” November 19, 1968 William D. Hersey “An Amazing Demonstration of Memory” January 28, 1969 Domenic DiMaggio, Former Member, Boston Red Sox “Baseball” November 18, 1969 Frank J. Zeo “What’s Ahead for the Taxpayer?” March 25, 1969 Charles A. Fager, M.D. “The S.S. Hope” January 27, 1970 Ned Martin, Red Sox Broadcaster “Sports” March 31, 1970 David H. Locke, MA State Senator “How Can We Reduce State Taxes?” November 17, 1970 Laurence R. Buxbaum Chief, Consumer Protection Agency February 23, 1971 Steven A. Minter Commissioner of Welfare November 16, 1971 Robert White “The Problem of Shoplifting” January 25, 1972 Nicholas J. Fiumara, M.D. “Boston After Dark” November 14, 1972 E. G. Matthews “The Play of the Senses” January 23, 1973 Joseph M. Jordan “The Vice Scene in Boston” November 13, 1973 Jack Crowley “A Demonstration by the Nether-hair Kennels” January 22, 1974 David R. Palmer “Whither Goest the Market for Securities?” February 19, 1974 David J. Lucey “Your Highway Safety” November 19, 1974 Don Nelson, Boston Celtics “Life Among the Pros” January 28, 1975 The Honorable John W. McCormack, Speaker of the House “Memories of Washington” Speakers_BDA_1966_to_Current Page #1 February 25, 1975 David A. -

Newslink Newslink

EWSEWS INKINK THE BEACON HILL INSTITUTE NN LL AT SUFFOLK UNIVERSITY Vol. 3, No. 3 IDEAS AND UPDATES ON PUBLIC POLICY Spring 1999 BHI's MBTA study: Derail budget buster fter decades of signing a mal. Fares were last raised in 1991. Years later usage, the legislature is simply substituting blank check for the Massa- when the Weld Administration’s blueprint for one flawed budget practice for another. A chusetts Bay Transportation privatization proved to be politically unpopu- Authority, the Common- lar, the MBTA’s financing problems left the An efficient and fare solution wealth is planning to change the way tax- collective radar screen. Consider the following: payers are charged for public transporta- And so the T chugs along on a bud- tion. But will these changes be enough? A get that now approaches $1 billion per year, • The MBTA could save $58.87 million in new BHI study, Financing the MBTA: An of which only about 17% is derived from fares. FY 2000 operating costs by increasing effi- Efficient and Fare Solution, raises doubts that Now, however, even supporters of ciency to levels achieved by comparable they will. public transportation have, in effect, declared, transit authorities and without sacrificing For years, the “This is no way to run service. MBTA has simply billed the a railroad.” That’s be- state for rapid transit, bus cause the state faces a • Massachusetts taxpayers pay on aver- and commuter line services debt ceiling imposed age $203 per year each to subsidize the it has provided to commut- by expenditures and MBTA, whether they use the system or not. -

Charlestown Annual Veterans' Dinner

VOL. 118 - NO. 46 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 14, 2014 $.35 A COPY CHARLESTOWN ANNUAL VETERANS’ DINNER by Sal Giarratani Once again, all Charlestown veterans and those presently on active duty, family and friends packed the Knights of Columbus on Medford Street last Friday, November 7 at the 2nd Annual Veterans’’ Dinner sponsored by the Abraham Lincoln Post 11, GAR. This year’s gathering more than doubled in size over previous gatherings at Post 11 GAR on Green Street. Post Commander Joe Zuffante, hoped next year’s gathering and those to follow will keep growing in participation. As a member of Post 11, I very much appreciated the tribute this year to all those Townies who served during the Vietnam War, especially honoring those who paid the ultimate sacrifice. This annual pre-Veterans Day appreciation dinner is held to honor all who served in the Armed Forces. It was 96 years ago on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, that World War I came to an end and hun- dreds of thousands of American soldiers began the long voyage home. This year, in the months to come many of our troops will be coming home and sadly many others will be going off to harm’s way leaving their loving fami- lies behind to defend American principles. As a Vietnam era U.S. Air Force veteran, I remain especially cognitive of the lack of appreciation and honor due to them when they returned from the war which had grown quite unpopular at home in the U.S. -

Roger Wheeler Detective Mike Huff Tells the Riveting Story of Why the Boston Mafia Murdered This Tulsa Businessman

Roger Wheeler Detective Mike Huff tells the riveting story of why the Boston Mafia murdered this Tulsa businessman. Chapter 1 — 1:20 Introduction Announcer: Businessman Roger Wheeler, the former Chairman of Telex Corporation and former owner of World Jai Alai, was murdered May 27, 1981, at Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma, while sitting in his car. At age 55, he was leaving the golf course after his weekly game of golf and was murdered for uncovering an embezzlement scheme that was going on at his business, World Jai Alai. Linked to the murder were H. Paul Rico, John Callahan, Whitey Bulger, Steve Flemmi, and Johnny Martarano. The first Tulsa police detective to arrive at the scene of the crime was Homicide Detective Mike Huff. Immediate suspicions led to speculation that the murder was a mob hit, but when at Huff’s request, the Tulsa FBI asked the Boston FBI office for help, they received a terse reply that Boston had ruled out a Boston mafia connection. Thus began years of a relentless pursuit by Mike Huff, with resources provided by the Tulsa Police Department and other organizations in Boston and federal agencies to identify those connected to the murder of Roger Wheeler. Listen to Mike Huff talk about the murder from the day it happened to the conviction of Whitey Bulger on the Oklahoma oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 2 — 8:50 Homicide John Erling: My name is John Erling and today’s date is June 13, 2013. So, Mike, state your full name, your date of birth and your present age, please. -

LIBERTY PLEDGE NEWSLETTER Libertarian National Committee, Inc

Published for the friends and supporters of the Libertarian Party LIBERTY PLEDGE NEWSLETTER Libertarian National Committee, Inc. + 2600 Virginia Ave, NW, Suite 200 + Washington, DC 20037 + Phone: (202) 333-0008 + Fax: (202) 333-0072 www.LP.org November 2012 From United Press International: Libertarian Party Buoyant By Gerry Harrington Critics say the commission excludes third-party and Cravings for less Washington gave the Libertarian independent candidates. Besides Florida, swing presidential entrant a record vote count. states this year were Colorado, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia and The nearly 1.2 million votes won by Libertarian Wisconsin. Party nominee Gary Johnson, a former two-term Republican New Mexico governor, supported Howell told UPI the Libertarian Party -- whose public-opinion polls showing "consistently that a slogan is "minimum government, maximum majority of Americans want less government than freedom" -- planned to move forward by seeking to we have today," party Executive Director Carla enlarge the party through alliances with supporters Howell told United Press International. of U.S. Rep. Ron Paul, R-Texas, who sought this His vote count beat the previous Libertarian Party year's GOP nomination for president and is widely record, set in 1980 by lawyer-politician Ed Clark, of known for his libertarian positions. 921,128 votes, or 1 percent of the nationwide total. Johnson had the strongest showing as a percentage It would also seek ties with "tea partiers, of statewide presidential votes in Alaska, Maine, disenfranchised Republicans, independents, Montana, New Mexico and Wyoming, the UPI Democrats" and others who "share our goals and analysis showed. -

A Former Higher Education Reporter Reflects on Coverage

ONTHEBEAT A Former Higher Education Reporter Reflects on Coverage Jon Marcus hen colleges and univer- that higher education coverage in particular should be more, not less, questioning and critical. In other words, higher edu- sities finally responded W cation coverage leaves a lot to be desired not because it’s too this fall to the decade of complaints tough, but because it isn’t tough enough. about their escalating costs, it wasn’t Many editors seem to read “education beat” as “training ground for new reporters.” Few people want the job, and most by explaining why tuition has consis- get out of it before they learn the difference between FTE and tently increased at double the rate of headcount, with the connivance of news organizations that pay too little attention to the topic. The education beat has an inflation or by outlining the measures indisputably high turnover rate—even in New England where they were taking to save money. higher education is a major industry. And make no mistake: higher education is an industry. It No, the higher education honchos, in their wisdom, is no coincidence that some of the best higher education cov- launched a campaign to explain how, with the right combi- erage in New England and elsewhere appears in business nation of loans and savings, a family could still afford the publications. As much as colleges and universities resist the $120,000-plus price of an undergraduate degree from a pri- idea that they offer a consumer product, the ones that do well vate, four-year college or university. -

Participatory Propaganda Model 1

A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 1 Participatory Propaganda: The Engagement of Audiences in the Spread of Persuasive Communications Alicia Wanless Michael Berk Director of Strategic Communications, Visiting Research Fellow, SecDev Foundation Centre for Cyber Security and International [email protected] Relations Studies, University of Florence [email protected] Paper presented at the "Social Media & Social Order, Culture Conflict 2.0" conference organized by Cultural Conflict 2.0 and sponsored by the Research Council of Norway on 1 December 2017, Oslo. To be published as part of the conference proceedings in 2018. A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 2 Abstract Existing research on aspects of propaganda in a digital age tend to focus on isolated techniques or phenomena, such as fake news, trolls, memes, or botnets. Providing invaluable insight on the evolving human-technology interaction in creating new formats of persuasive messaging, these studies lend to an enriched understanding of modern propaganda methods. At the same time, the true effects and magnitude of successful influencing of large audiences in the digital age can only be understood if target audiences are perceived not only as ‘objects’ of influence, but as ‘subjects’ of persuasive communications as well. Drawing from vast available research, as well as original social network and content analyses conducted during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, this paper presents a new, qualitatively enhanced, model of modern propaganda – “participatory propaganda” - and discusses its effects on modern democratic societies. Keywords: propaganda, Facebook, social network analysis, content analysis, politics A PARTICIPATORY PROPAGANDA MODEL 3 Participatory Propaganda: The Engagement of Audiences in the Spread of Persuasive Communications Rapidly evolving information communications technologies (ICTs) have drastically altered the ways individuals engage in the public information domain, including news ways of becoming subjected to external influencing. -

A Quick Guide to the Foreign Policy Views of the Republican Presidential Candidates I Nstitute Esearch R

A QUICK GUIDE TO THE FOREIGN POLICY VIEWS OF THE EPUBLICAN RESIDENTIAL ANDIDATES R P C NSTITUTE I ESEARCH R OLICY P By Brandon George Whitehill July 2015 OREIGN F 1 | FPRI 1 Because of the logistics of trade deals, support for TPP with concurrent opposition to TPA is akin to opposition to TPP. 2 | FPRI 3 | FPRI 4 | FPRI 5 | FPRI 6 | FPRI 2 Paul, Rand. Interview with Manu Raju. Politico, August 28, 2012. 3 Paul, Rand. "Campaign Launch." (Transcript, Louisville, KY). Time Magazine, April 7, 2015. 4 Sullivan, Sean. "Rand Paul: 'We still have chaos in Iraq.'" The Washington Post, May 17, 2015. 5 Ibid. 6 Paul, Rand. Interview with Joe Scarborough. Morning Joe. MSNBC, May 27, 2015. 7 A Defense Intelligence Agency memo from October 2012 confirms that the United States did knowingly facilitate the movement of weapons from Libyan rebels to two Syrian ports with the intention of distributing them to rebels. DIA Report 7 | FPRI 8 Paul, Rand. Interview with Joe Scarborough. Morning Joe. MSNBC, May 27, 2015. 9 Ibid. 10 Paul, Rand. Speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference. The American Conservative Union. National Harbor, MD, February 27, 2015. 11 Ibid. 12 Paul, Rand. Interview with Hugh Hewitt. The Hugh Hewitt Show, April 10, 2015 13 Paul, Rand. Interview with Igor Bobic. The Huffington Post, March 15, 2015. 14 Paul, Rand. Speech at the Values Voters Summit. Family Research Council. Washington, DC, September 19, 2012. 15 Paul, Rand. Post on Iran Nuclear Deal. Official Rand Paul Facebook Page, July 14, 2015. 16 Paul, Rand. -

2013 Annual Report

Town of Arlington Massachusetts 2013 Annual Report Board of Selectmen Daniel J. Dunn, ChairmaN Diane M. Mahon, Vice Chairman Kevin F. Greeley Steven M. Byrne Joseph A. Curro, Jr. Town Manager Adam W. Chapdelaine Table of Contents Executive Services Education Board of Selectmen 3 Arlington Public Schools 73 Town Manager 5 Minuteman Regional Vocational Technical School District 77 Financial Management Services Finance Committee 11 Cultural & Historical Activities Office of the Treasurer & 11 Arlington Cultural Council 81 Collector of Taxes Arlington Cultural Commission 82 Comptroller/Telephone 13 Arlington Historical Commission 83 Board of Assessors 14 Historic District Commissions 83 Fiscal Year 2014 21 Cyrus E. Dallin Art Museum 84 Independent Auditor’s Report 22 Community Development Department of Public Works 33 Planning & Community Development/ Redevelopment Board 86 Community Safety Permanent Town Building Committee 89 Police Department 38 Zoning Board of Appeals 89 Fire Department 45 Conservation Commission 89 Inspectional Services 48 Open Space Committee 91 Transportation Advisory Committee 92 Central Management Services Bicycle Advisory Committee 94 Human Resources Department 49 Arlington Housing Authority 94 Equal Opportunity 49 Vision 2020 96 Information Technology 50 Legal Department 52 Legislative Moderator 106 Health & Human Services Town Meeting Members 107 Health and Human Services 54 2013 Annual Town Meeting 110 Board of Health 54 Special Town Meeting: April 24, 2013 113 Health Department 54 Board of Youth Services / 58 -

Title Author Reason for LRC Rejection 101 Places to Get F*Cked Up

Title Title Author Reason for LRC Rejection 101 Places to Get F*cked up before you die-the Ultimate Travel guide to Partying Around the World Matador Network edited by David SDrug paraphernalia addicted Zane containing explicit representation of sexual acts & bondage Adult WebCam Studio 101 Darby Jones promoting illegal activities America's Racial Powder Keg Victor Thorn descriptions that may lead to group disruption Bad Blood II Tuffy sexually explicit Beyond this Horizon Robert A. Heilein security concerns Black Mafia Family Mara Shalhoup security threat group concerns Black Mass Dick Lehr & Gerard O'Neill security threat group Black Racism, White Victims John Publis security threat groups Blood in the Water Heather Ann Thompson security concerns-encourage group disruption Blood of My Brother II The Face Off Zoe & Yusuf T. Woods security concerns Blood of My Brother III The Begotten Son Zoe & Yusuf T. Woods security concerns Blood of My Brother IV Behind the Mask Zoe & Yusuf T. Woods security concerns Blood of My Brother The Battle for Supremacy on the Streets Zoe & Yusuf T. Woods security concerns Bound Lorelei James containing explicit representation of sexual acts & bondage Brutul-the untold story of my life inside Whitey Bulger's Irish Mob Kevin Weeks and Phyllis Karas Gang activities Buckland's Book of Saxon Witchcraft Raymond Buckland Procedures for brewing alcohol Cessna 150 A Pilot's Guide Jeremy M. Pratt security concerns Collected Works George Lincoln Rockwell descriptions that may lead to group disruption Coming out of Concrete Closets Jason Lydon et. Al. unlawful sexual practice Complete guide to non-prescription drugs book used to promote drug use, if needed for medical in library Conceptions III Luis Royo sexually explicit Cryptogram-A-Day Louise B.