A Former Higher Education Reporter Reflects on Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 21, 2014 Vol. 118 No. 47

VOL. 118 - NO. 47 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 21, 2014 $.35 A COPY Thanksgiving vs. Roseland and Massport Celebrate Opening of the Big Box Company PORTSIDE AT EAST PIER BUILDING 7 by Nicole Vellucci Ribbon-Cutting Held for Luxury Residential and Retail Complex in East Boston Thanksgiving, a Roseland, a subsidiary of day synonymous Mack-Cali Realty Corpora- with the word fam- tion (NYSE: CLI), in partner- ily in American cul- ship with the Massachusetts ture, has become Port Authority (Massport), more about the dol- hosted a ribbon-cutting for lar than together- the opening of Portside at ness. As a child, our East Pier Building 7, its flag- Thanksgiving ship luxury residential and preparations began retail complex located at 50 weeks prior to the Lewis Street in East Boston. main event with planning the menu, inviting family and Joined by Senator Anthony friends and endless trips to the grocery store. My father Petruccelli and State Rep. would post the dinner menu on our kitchen refrigerator Carlo Basile, Roseland and and everyone was asked to add their requests. Turkey day Massport celebrated the morning began with naming our bird (or birds since one completion of the initial thirty-pound turkey was not enough because you never building in East Boston’s first knew who would stop by) and preparation of all the deli- residential waterfront devel- Left to right: State Senator Anthony Petruccelli, cious accompaniments. Besides the wonderful aroma of this opment project in decades. Roseland President Marshall Tycher, City Councilor Sal feast filling our home, what I remember most is all the Portside at East Pier Build- LaMattina, State Rep Carlo Basile, BRA Director Brian Golden and Massport CEO Tom Glynn. -

(Pdf) Download

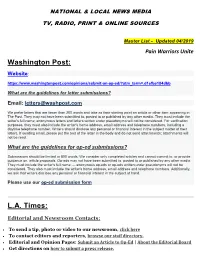

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Boston Druggists' Association

BOSTON DRUGGISTS’ ASSOCIATION SPEAKERS, 1966 to 2019 Date Speaker Title/Topic February 15, 1966 The Honorable John A. Volpe Governor of Massachusetts March 22, 1966 William H. Sullivan, Jr. President, Boston Patriots January 24, 1967 Richard E. McLaughlin Registry of Motor Vehicles March 21, 1967 Hal Goodnough New York Mets Baseball February 27, 1968 Richard M. Callahan “FDA in Boston” January 30, 1968 The Honorable Francis W. Sargeant “The Challenge of Tomorrow” November 19, 1968 William D. Hersey “An Amazing Demonstration of Memory” January 28, 1969 Domenic DiMaggio, Former Member, Boston Red Sox “Baseball” November 18, 1969 Frank J. Zeo “What’s Ahead for the Taxpayer?” March 25, 1969 Charles A. Fager, M.D. “The S.S. Hope” January 27, 1970 Ned Martin, Red Sox Broadcaster “Sports” March 31, 1970 David H. Locke, MA State Senator “How Can We Reduce State Taxes?” November 17, 1970 Laurence R. Buxbaum Chief, Consumer Protection Agency February 23, 1971 Steven A. Minter Commissioner of Welfare November 16, 1971 Robert White “The Problem of Shoplifting” January 25, 1972 Nicholas J. Fiumara, M.D. “Boston After Dark” November 14, 1972 E. G. Matthews “The Play of the Senses” January 23, 1973 Joseph M. Jordan “The Vice Scene in Boston” November 13, 1973 Jack Crowley “A Demonstration by the Nether-hair Kennels” January 22, 1974 David R. Palmer “Whither Goest the Market for Securities?” February 19, 1974 David J. Lucey “Your Highway Safety” November 19, 1974 Don Nelson, Boston Celtics “Life Among the Pros” January 28, 1975 The Honorable John W. McCormack, Speaker of the House “Memories of Washington” Speakers_BDA_1966_to_Current Page #1 February 25, 1975 David A. -

Michael C. Keith

_____________________________________ M I C H A E L C. K E I T H _________________________________ 3 Howard Street email: [email protected] Easton, MA 02375 Phone/Fax (508) 238-7408 < www.michaelckeith.com > EDUCATION Ph.D. -- University of Rhode Island, 1998. Dissertation Title: Commercial Underground Radio and the Sixties: An Oral History and Narrative M.A. -- University of Rhode Island, 1977 (Highest Honors) Thesis Title: The Obsessed Characters in the Novels of Muriel Spark B.A. -- University of Rhode Island, 1975 (Highest Honors) ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 1993 - Adj. Associate Professor of Communication Boston College, Boston, MA. (Assistant Chair, 1995-1998). 1992 - 93 Visiting Professor of Communication Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. 1992 - 93 Chair of Education Museum of Broadcast Communications, Chicago, IL. 1990 - 92 Visiting Professor of Communication The George Washington University, Washington, DC. 1978 - 90 Director of Radio and Television and Associate Professor of Communication. Dean College, Franklin, MA. (Interim Chairperson of English and Communication Departments, 1988-89). 1989 - 90 Adjunct Lecturer of Communication Emerson College, Boston, MA. 1977 - 78 Adjunct Lecturer of Communication Roger Williams University, Bristol, R.I. PUBLICATIONS BOOKS --Academic Monographs-- Norman Corwin’s ‘One World Flight:’ The Lost Journal of Radio’s Greatest Writer, ed. (with Mary Ann Watson) New York: Continuum Books, 2009. Sounds of Change: FM Broadcasting in America (with Christopher Sterling) Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008 Radio Cultures: The Sound Medium in American Life, ed. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2008. The Quieted Voice: The Rise and Demise of Localism in American Radio. (with Robert Hilliard) Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005. -

PRJVIES Time, Turning Down Carole R

17 Radio Programming WHILE OTHERS NOSEDIVE WCOZ-FM Remains Rock's Rock Of Gibraltar In Boston Market By JON KELLER BOSTON -"The spring (Arbi- Dave Croninger when asked to ex- did back in 1974," says another p.d. tron) book is the beginning of a new plain his station's sagging fortunes, WBZ experimented with an all -news trend in the market," cheers WCOZ - "I'll really have to think that one block in afternoon drive in the late FM program director Andy Beau - over." '70s, and rumor has it considering bien "and its exciting to watch it One of the dayparts WHDH will that format again for certain day - happen." be thinking about hard as it looks for parts. "With the shift from AM to Beaubien has reason to be happy. reasons why its share is down to 8.5 FM by adult contemporary listeners, While longtime AM heavyweights (from 10.3 in the winter book and an the AM stations just have to re -ori- WBZ and WHDH took nosedives 11.1 in spring, 1980) will probably ent," points out Beaubien of WCOZ. and a pair of RKO General outlets be nighttime. Despite the assertion Over at RKO General's WRKO, showed strong upward movement, of WHDH program director Bob the first stage of an ongoing shift WCOZ -FM remained Boston ra- Adams that "one monkey don't stop from adult contemporary to a for- dio's Rock of Gibraltar. The hard - no show," the departure of talk - mat emphasizing news, talk, and edged AOR station scored an 11.1, show host David Brudnoy in March sports is already paying dividends. -

Unhelpful Alfred C

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers July 1996 Unhelpful Alfred C. Yen Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Alfred C. Yen. "Unhelpful." Iowa Law Review 81, (1996): 1573-1583. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unhelpful Alfred C. Yen* Professor Jim Chen apparently cares deeply about racial harmony in America and has strong ideas about how to achieve the utopia he imagines. It's a pity, then, that his article Unloving' contributes so little to honest discourse about that subject. The backdrop for this negative reaction to Unloving is the sorry state of race discourse (and political discourse more generally) in America today. Race is a difficult, complicated problem, and reasonable people of good will disagree passionately over the best ways to end racial injustice. Ideally, those who disagree ought to engage in honest, respectful, and open-minded dialogue in the hope of finding common ground. In this conversation, each participant would treat the others with respect and make a sincere effort to fairly consider all arguments being made. Unfortunately, the dialogue I envision rarely happens in America, at least not in public. Americans live on sound bites. -

Connection Cover.QK

Also Inside: CONNECTION Index of Authors, 1986-1998 CONNECTION NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT VOLUME XIII, NUMBER 3 FALL 1998 $2.50 N EW E NGLAND W ORKS Volume XIII, No. 3 CONNECTION Fall 1998 NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COVER STORIES 15 Reinventing New England’s Response to Workforce Challenges Cathy E. Minehan 18 Where Everyone Reads … and Everyone Counts Stanley Z. Koplik 21 Equity for Student Borrowers Jane Sjogren 23 On the Beat A Former Higher Education Reporter Reflects on Coverage COMMENTARY Jon Marcus 24 Elevating the Higher Education Beat 31 Treasure Troves John O. Harney New England Museums Exhibit Collection of Pressures 26 Press Pass Alan R. Earls Boston News Organizations Ignore Higher Education Soterios C. Zoulas 37 Moments of Meaning Religious Pluralism, Spirituality 28 Technical Foul and Higher Education The Growing Communication Gap Between Specialists Victor H. Kazanjian Jr. and the Rest of Us Kristin R. Woolever 40 New England: State of Mind or Going Concern? Nate Bowditch DEPARTMENTS 43 We Must Represent! A Call to Change Society 5 Editor’s Memo from the Inside John O. Harney Walter Lech 6 Short Courses Books 46 Letters Reinventing Region I: The State of New England’s 10 Environment by Melvin H. Bernstein Sven Groennings, 1934-1998 And Away we Go: Campus Visits by Susan W. Martin 11 Melvin H. Bernstein Down and Out in the Berkshires by Alan R. Earls 12 Data Connection 14 Directly Speaking 52 CONNECTION Index of Authors, John C. Hoy 1986-1998 50 Campus: News Briefly Noted CONNECTION/FALL 1998 3 EDITOR’S MEMO CONNECTION Washington State University grad with a cannon for an arm is not exactly the kind NEW ENGLAND’S JOURNAL ONNECTION OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT of skilled worker C has obsessed about during its decade-plus of exploring A the New England higher education-economic development nexus. -

Newslink Newslink

EWSEWS INKINK THE BEACON HILL INSTITUTE NN LL AT SUFFOLK UNIVERSITY Vol. 3, No. 3 IDEAS AND UPDATES ON PUBLIC POLICY Spring 1999 BHI's MBTA study: Derail budget buster fter decades of signing a mal. Fares were last raised in 1991. Years later usage, the legislature is simply substituting blank check for the Massa- when the Weld Administration’s blueprint for one flawed budget practice for another. A chusetts Bay Transportation privatization proved to be politically unpopu- Authority, the Common- lar, the MBTA’s financing problems left the An efficient and fare solution wealth is planning to change the way tax- collective radar screen. Consider the following: payers are charged for public transporta- And so the T chugs along on a bud- tion. But will these changes be enough? A get that now approaches $1 billion per year, • The MBTA could save $58.87 million in new BHI study, Financing the MBTA: An of which only about 17% is derived from fares. FY 2000 operating costs by increasing effi- Efficient and Fare Solution, raises doubts that Now, however, even supporters of ciency to levels achieved by comparable they will. public transportation have, in effect, declared, transit authorities and without sacrificing For years, the “This is no way to run service. MBTA has simply billed the a railroad.” That’s be- state for rapid transit, bus cause the state faces a • Massachusetts taxpayers pay on aver- and commuter line services debt ceiling imposed age $203 per year each to subsidize the it has provided to commut- by expenditures and MBTA, whether they use the system or not. -

A Man for All Reasons: David Brudnoy Was a Real Compassionate Conservative by HARVEY A

A man for all reasons: David Brudnoy was a real compassionate conservative BY HARVEY A. SILVERGLATE DAVID BRUDNOY’S untimely death, on December 9, spurred a massive number of public reminiscences by friends, acquaintances, listeners, and just about everyone who ever crossed his path. The talk-show host, author, columnist, movie critic, teacher, and man about town was the perfect everything, each seemed to say. He did so many things well, in so many different spheres, and yet remained so human, with a special talent for humor and friendship. It was also often said that Brudnoy, "even though a conservative," was beloved and respected by the rich and poor, the well-educated and barely educated, the white-collar and blue-collar alike. MEETING OF MINDS: the author, right, with long-time friend David Brudnoy, It’s true that Brudnoy’s anomalous political philosophy who could connect as readily with liberals as with fellow conservatives. deviated considerably from both liberal and conservative dogma. His support of gay marriage and his opposition to obscenity laws separated him from many conservatives, while his criticisms of the "nanny state" conflicted with liberal doctrine. (He laughed appreciatively whenever I, a devoted liberal civil libertarian, reminded him of Barney Frank’s pungent observation that some conservatives believe that life begins at conception and ends at birth.) Indeed, a month before his death, he and I agreed to do a series of joint columns for the Boston Phoenix taking aim at the current-day idiocies that pollute both conservative and liberal political life. Yet the common view of Brudnoy is that liberals and conservatives managed to tolerate him despite his politics, by virtue of his magnetic and endearing personal qualities. -

Charlestown Annual Veterans' Dinner

VOL. 118 - NO. 46 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 14, 2014 $.35 A COPY CHARLESTOWN ANNUAL VETERANS’ DINNER by Sal Giarratani Once again, all Charlestown veterans and those presently on active duty, family and friends packed the Knights of Columbus on Medford Street last Friday, November 7 at the 2nd Annual Veterans’’ Dinner sponsored by the Abraham Lincoln Post 11, GAR. This year’s gathering more than doubled in size over previous gatherings at Post 11 GAR on Green Street. Post Commander Joe Zuffante, hoped next year’s gathering and those to follow will keep growing in participation. As a member of Post 11, I very much appreciated the tribute this year to all those Townies who served during the Vietnam War, especially honoring those who paid the ultimate sacrifice. This annual pre-Veterans Day appreciation dinner is held to honor all who served in the Armed Forces. It was 96 years ago on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, that World War I came to an end and hun- dreds of thousands of American soldiers began the long voyage home. This year, in the months to come many of our troops will be coming home and sadly many others will be going off to harm’s way leaving their loving fami- lies behind to defend American principles. As a Vietnam era U.S. Air Force veteran, I remain especially cognitive of the lack of appreciation and honor due to them when they returned from the war which had grown quite unpopular at home in the U.S. -

Roger Wheeler Detective Mike Huff Tells the Riveting Story of Why the Boston Mafia Murdered This Tulsa Businessman

Roger Wheeler Detective Mike Huff tells the riveting story of why the Boston Mafia murdered this Tulsa businessman. Chapter 1 — 1:20 Introduction Announcer: Businessman Roger Wheeler, the former Chairman of Telex Corporation and former owner of World Jai Alai, was murdered May 27, 1981, at Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma, while sitting in his car. At age 55, he was leaving the golf course after his weekly game of golf and was murdered for uncovering an embezzlement scheme that was going on at his business, World Jai Alai. Linked to the murder were H. Paul Rico, John Callahan, Whitey Bulger, Steve Flemmi, and Johnny Martarano. The first Tulsa police detective to arrive at the scene of the crime was Homicide Detective Mike Huff. Immediate suspicions led to speculation that the murder was a mob hit, but when at Huff’s request, the Tulsa FBI asked the Boston FBI office for help, they received a terse reply that Boston had ruled out a Boston mafia connection. Thus began years of a relentless pursuit by Mike Huff, with resources provided by the Tulsa Police Department and other organizations in Boston and federal agencies to identify those connected to the murder of Roger Wheeler. Listen to Mike Huff talk about the murder from the day it happened to the conviction of Whitey Bulger on the Oklahoma oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 2 — 8:50 Homicide John Erling: My name is John Erling and today’s date is June 13, 2013. So, Mike, state your full name, your date of birth and your present age, please. -

LIBERTY PLEDGE NEWSLETTER Libertarian National Committee, Inc

Published for the friends and supporters of the Libertarian Party LIBERTY PLEDGE NEWSLETTER Libertarian National Committee, Inc. + 2600 Virginia Ave, NW, Suite 200 + Washington, DC 20037 + Phone: (202) 333-0008 + Fax: (202) 333-0072 www.LP.org November 2012 From United Press International: Libertarian Party Buoyant By Gerry Harrington Critics say the commission excludes third-party and Cravings for less Washington gave the Libertarian independent candidates. Besides Florida, swing presidential entrant a record vote count. states this year were Colorado, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia and The nearly 1.2 million votes won by Libertarian Wisconsin. Party nominee Gary Johnson, a former two-term Republican New Mexico governor, supported Howell told UPI the Libertarian Party -- whose public-opinion polls showing "consistently that a slogan is "minimum government, maximum majority of Americans want less government than freedom" -- planned to move forward by seeking to we have today," party Executive Director Carla enlarge the party through alliances with supporters Howell told United Press International. of U.S. Rep. Ron Paul, R-Texas, who sought this His vote count beat the previous Libertarian Party year's GOP nomination for president and is widely record, set in 1980 by lawyer-politician Ed Clark, of known for his libertarian positions. 921,128 votes, or 1 percent of the nationwide total. Johnson had the strongest showing as a percentage It would also seek ties with "tea partiers, of statewide presidential votes in Alaska, Maine, disenfranchised Republicans, independents, Montana, New Mexico and Wyoming, the UPI Democrats" and others who "share our goals and analysis showed.