Cultural and Cognitive Implications of the Trobriand Islanders' Gradual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borobudur 1 Pm

BOROBUDUR SHIP RECONSTRUCTION: DESIGN OUTLINE The intention is to develop a reconstruction of the type of large outrigger vessels depicted at Borobudur in a form suitable for ocean voyaging DISTANCES AND DURATION OF VOYAGES and recreating the first millennium Indonesian voyaging to Madagascar and Africa. Distances: Sunda Strait to Southern Maldives: Approx. 1600 n.m. The vessel should be capable of transporting some Maldives to Northern Madagascar: Approx. 1300 n.m. 25-30 persons, all necessary provisions, stores and a cargo of a few cubic metres volume. Assuming that the voyaging route to Madagascar was via the Maldives, a reasonably swift vessel As far as possible the reconstruction will be built could expect to make each leg of the voyage in using construction techniques from 1st millennium approximately two weeks in the southern winter Southeast Asia: edge-doweled planking, lashings months when good southeasterly winds can be to lugs on the inboard face of planks (tambuku) to expected. However, a period of calm can be secure the frames, and multiple through-beams to experienced at any time of year and provisioning strengthen the hull structure. for three-four weeks would be prudent. The Maldives would provide limited opportunity There are five bas-relief depictions of large vessels for re-provisioning. It can be assumed that rice with outriggers in the galleries of Borobudur. They sufficient for protracted voyaging would be carried are not five depictions of the same vessel. While from Java. the five vessels are obviously similar and may be seen as illustrating a distinct type of vessel there are differences in the clearly observed details. -

Gifts and Commodities (Second Edition)

GIFTS AND COMMODITIES Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com GIFTS AND COMMODITIES (SECOND EditIon) C. A. Gregory Foreword by Marilyn Strathern New Preface by the Author Hau Books Chicago © 2015 by C. A. Gregory and Hau Books. First Edition © 1982 Academic Press, London. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-1-3 LCCN: 2014953483 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. For Judy, Polly, and Melanie. Contents Foreword by Marilyn Strathern xi Preface to the first edition xv Preface to the second edition xix Acknowledgments liii Introduction lv PART ONE: CONCEPTS I. THE COmpETING THEOriES 3 Political economy 3 The theory of commodities 3 The theory of gifts 9 Economics 19 The theory of modern goods 19 The theory of traditional goods 22 II. A framEWORK OF ANALYSIS 25 The general relation of production to consumption, distribution, and exchange 26 Marx and Lévi-Strauss on reproduction 26 A simple illustrative example 30 The definition of particular economies 32 viii GIFTS AND COMMODITIES III.FTS GI AND COMMODITIES: CIRCULATION 39 The direct exchange of things 40 The social status of transactors 40 The social status of objects 41 The spatial aspect of exchange 44 The temporal dimension of exchange 46 Value and rank 46 The motivation of transactors 50 The circulation of things 55 Velocity of circulation 55 Roads of gift-debt 57 Production and destruction 59 The circulation of people 62 Work-commodities 62 Work-gifts 62 Women-gifts 63 Classificatory kinship terms and prices 68 Circulation and distribution 69 IV. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 6 MILNE BAY PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.L. Hide, R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, T. Betitis, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, L. Kurika, E. Lowes, D.K. Mitchell, S.S. Rangai, M. Sakiasi, G. Sem and B. Suma Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Hide, R.L., Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Betitis, T., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Kurika, L., Lowes, E., Mitchell, D.K., Rangai, S.S., Sakiasi, M., Sem, G. and Suma,B. (2002). Milne Bay Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 6. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: Milne Bay Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 6 0 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. I. Hide, Robin Lamond. II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. 6). 630.99541 Cover Photograph: The late Gore Gabriel clearing undergrowth from a pandanus nut grove in the Sinasina area, Simbu Province (R.L. -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event

Linguistic Evidence for a Prehistoric Polynesia—Southern California Contact Event KATHRYN A. KLAR University of California, Berkeley TERRY L. JONES California Polytechnic State University Abstract. We describe linguistic evidence for at least one episode of pre- historic contact between Polynesia and Native California, proposing that a borrowed Proto—Central Eastern Polynesian lexical compound was realized as Chumashan tomol ‘plank canoe’ and its dialect variants. Similarly, we suggest that the Gabrielino borrowed two Polynesian forms to designate the ‘sewn- plank canoe’ and ‘boat’ (in general, though probably specifically a dugout). Where the Chumashan form speaks to the material from which plank canoes were made, the Gabrielino forms specifically referred to the techniques (adzing, piercing, sewing). We do not suggest that there is any genetic relationship between Polynesian languages and Chumashan or Gabrielino, only that the linguistic data strongly suggest at least one prehistoric contact event. Introduction. Arguments for prehistoric contact between Polynesia and what is now southern California have been in print since the late nineteenth century when Lang (1877) suggested that the shell fishhooks used by Native Hawaiians and the Chumash of Southern California were so stylistically similar that they had to reflect a shared cultural origin. Later California anthropologists in- cluding the archaeologist Ronald Olson (1930) and the distinguished Alfred Kroeber (1939) suggested that the sewn-plank canoes used by the Chumash and the Gabrielino off the southern California coast were so sophisticated and uni- que for Native America that they likely reflected influence from Polynesia, where plank sewing was common and widespread. However, they adduced no linguistic evidence in support of this hypothesis. -

PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework September 2015 PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower/recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project information, including draft and final documents, will be made available for public review and comment as per ADB Public Communications Policy 2011. The environmental assessment and review framework will be uploaded to ADB website and will be disclosed locally. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... -

James Wharram and Hanneke Boon

68 James Wharram and Hanneke Boon 11 The Pacific migrations by Canoe Form Craft James Wharram and Hanneke Boon The Pacific Migrations the canoe form, which the Polynesians developed into It is now generally agreed that the Pacific Ocean islands superb ocean-voyaging craft began to be populated from a time well before the end of The Pacific double ended canoe is thought to have the last Ice Age by people, using small ocean-going craft, developed out of two ancient watercraft, the canoe and originating in the area now called Indonesia and the the raft, these combined produce a craft that has the Philippines It is speculated that the craft they used were minimum drag of a canoe hull and maximum stability of based on either a raft or canoe form, or a combination of a raft (Fig 111) the two The homo-sapiens settlement of Australia and As the prevailing winds and currents in the Pacific New Guinea shows that people must have been using come from the east these migratory voyages were made water craft in this area as early as 6040,000 years ago against the prevailing winds and currents More logical The larger Melanesian islands were settled around 30,000 than one would at first think, as it means one can always years ago (Emory 1974; Finney 1979; Irwin 1992) sail home easily when no land is found, but it does require The final long distance migratory voyages into the craft capable of sailing to windward Central Pacific, which covers half the worlds surface, began from Samoa/Tonga about 3,000 years ago by the The Migration dilemma migratory group -

Lepidoptera, Sphingidae)

©Entomologischer Verein Apollo e.V. Frankfurt am Main; download unter www.zobodat.at Nachr. entomol. Ver. Apollo, N. F. 36 (1): 55–61 (2015) 55 A checklist of the hawkmoths of Woodlark Island, Papua New Guinea (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) W. John Tennent, George Clapp and Eleanor Clapp W. John Tennent, Scientific Associate, Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, England; [email protected] George Clapp, 17 Tamborine Street, Hemmant, Queensland 4174, Australia Eleanor Clapp, 18 Adriana Drive, Buderim, Queensland 4556, Australia Abstract: A tabulated and annotated checklist of hawk exploration began again in 1973, and Woodlark Mining moths (Sphingidae) observed and collected by the first Limited (purchased by Kula Gold in 2007) was form ally au thor during three visits to Woodlark Island (Papua New granted a mining lease by the PNG govern ment in July Gui nea, Milne Bay Province) in 2010–2011 is presented. Nu me rous moths were attracted to mercury vapour bulbs 2014. used to illuminate a helicopter landing site and security A combination of an oceanic origin (Woodlark has lights around the administrative building at Bomagai Camp ne ver been connected by land to New Guinea), remo (Woodlark Mining Limited), near Kulumudau on the west te ness from the main island of New Guinea, and rather of the island. re stricted habitats, has resulted in an ecologically dis Keywords: Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Papua New Guinea, Milne Bay Province, Woodlark Island, range extension, tinct fauna. For example, there are no birds of paradise, distribution, new island records. bower birds, or wallabies on Woodlark, and only one species each of honey eater, sunbird and cuscus — all taxa Verzeichnis der Schwärmer von Woodlark Island, that are diverse and in some cases moderately numerous Papua-Neuguinea (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) elsewhere in Papua New Guinea. -

Pacific Colonisation and Canoe Performance: Experiments in the Science of Sailing

PACIFIC COLONISATION AND CANOE PERFORMANCE: EXPERIMENTS IN THE SCIENCE OF SAILING GEOFFREY IRWIN University of Auckland RICHARD G.J. FLAY University of Auckland The voyaging canoe was the primary artefact of Oceanic colonisation, but scarcity of direct evidence has led to uncertainty and debate about canoe sailing performance. In this paper we employ methods of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic analysis of sailing routinely used in naval architecture and yacht design, but rarely applied to questions of prehistory—so far. We discuss the history of Pacific sails and compare the performance of three different kinds of canoe hull representing simple and more developed forms, and we consider the implications for colonisation and later inter-island contact in Remote Oceania. Recent reviews of Lapita chronology suggest the initial settlement of Remote Oceania was not much before 1000 BC (Sheppard et al. 2015), and Tonga was reached not much more than a century later (Burley et al. 2012). After the long pause in West Polynesia the vast area of East Polynesia was settled between AD 900 and AD 1300 (Allen 2014, Dye 2015, Jacomb et al. 2014, Wilmshurst et al. 2011). Clearly canoes were able to transport founder populations to widely-scattered islands. In the case of New Zealand, modern Mäori trace their origins to several named canoes, genetic evidence indicates the founding population was substantial (Penney et al. 2002), and ancient DNA shows diversity of ancestral Mäori origins (Knapp et al. 2012). Debates about Pacific voyaging are perennial. Fifty years ago Andrew Sharp (1957, 1963) was sceptical about the ability of traditional navigators to find their way at sea and, more especially, to find their way back over long distances with sailing directions for others to follow. -

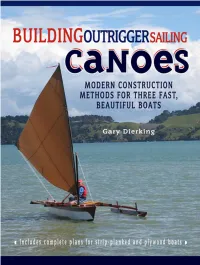

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent.