NSIAD-90-294 Apache Helicopter: Serious Logistical Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Modern Control Laws for the AH-64D in Hover/Low Speed Flight

Development of Modern Control Laws for the AH-64D in Hover/Low Speed Flight Jeffrey W. Harding 1 Scott J. Moody Geoffrey J. Jeram 2 Aviation Engineering Directorate U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Research, Development, and Engineering Center Redstone Arsenal, Alabama M. Hossein Mansur 3 Mark B. Tischler Aeroflightdynamics Directorate U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Research, Development, and Engineering Center Moffet Field, California ABSTRACT Modern control laws are developed for the AH-64D Longbow Apache to provide improved handling qualities for hover and low speed flight in a degraded visual environment. The control laws use a model following approach to generate commands for the existing partial authority stability augmentation system (SAS) to provide both attitude command attitude hold and translational rate command response types based on the requirements in ADS-33E. Integrated analysis tools are used to support the design process including system identification of aircraft and actuator dynamics and optimization of design parameters based on military handling qualities and control system specifications. The purpose is to demonstrate the potential for improving the low speed handling qualities of existing Army helicopters with partial authority SAS actuators through flight control law modifications as an alternative to a full authority, fly-by-wire, control system upgrade. NOTATION INTRODUCTION ACAH attitude command attitude hold The AH-64 Apache was designed in the late 70’s and went DH direction hold into service as the US Army’s most advanced day, night DVE degraded visual environment and adverse weather attack helicopter in 1986. The flight HH height hold control system was designed to meet the relevant handling HQ handling qualities qualities requirements based on MIL-F-8501 (Ref. -

Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information on a specific topic. Although documented briefings have been peer reviewed, they are not expected to be comprehensive and may present preliminary findings. Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options John Gordon IV, Peter A. Wilson, Jon Grossman, Dan Deamon, Mark Edwards, Darryl Lenhardt, Dan Norton, William Sollfrey Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; unlimited distribution The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

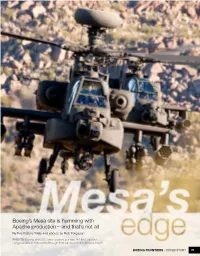

Boeing's Mesa Site Is Humming with Apache Production—And That's Not

Boeing’s Mesa site is humming with Apache production—and that’s not all By Eric Fetters-Walp and photos by Bob Ferguson PHOTO: Boeing and U.S. Army aviators put two AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopters through their paces over the Arizona desert. NOVEMBER 2011 BOEING FRONTIERS / COVER STORY 21 byMesa the numbers 1 ranking of Boeing Mesa’s business among all Arizona manufacturers 382 acres (155 hectares) comprising the Mesa site 576 number of Boeing suppliers or vendors in Arizona 1982 year Mesa site was established by Hughes Helicopters 4,500 approximate number of employees 8,300 hours volunteered by employees in 2010 he hot desert air above Mesa, making a growing array of components Ariz., frequently pulses with the for multiple Boeing aircraft. 1,900,000 T sound of Apache attack helicop- “We’ve gone from producing Block II ters as the intimidating machines are put Apaches two years ago to having three dollars given by Boeing Mesa and through their paces after emerging from and soon four production lines here today,” employees in charitable contributions the Boeing production line. first of the next-generation Apache Block III said Dave Koopersmith, Boeing Military during 2010 It’s a sound that’s become familiar over production models this fall. The U.S. Army Aircraft’s vice president of Attack Helicopter the nearly 30 years that the Mesa site has plans to order nearly 700 newly built or Programs and Mesa senior site executive, built Apaches for the U.S. Army and a remanufactured Block III helicopters, which referring to the two Apache production 2,000,000 growing number of international customers. -

Over Thirty Years After the Wright Brothers

ver thirty years after the Wright Brothers absolutely right in terms of a so-called “pure” helicop- attained powered, heavier-than-air, fixed-wing ter. However, the quest for speed in rotary-wing flight Oflight in the United States, Germany astounded drove designers to consider another option: the com- the world in 1936 with demonstrations of the vertical pound helicopter. flight capabilities of the side-by-side rotor Focke Fw 61, The definition of a “compound helicopter” is open to which eclipsed all previous attempts at controlled verti- debate (see sidebar). Although many contend that aug- cal flight. However, even its overall performance was mented forward propulsion is all that is necessary to modest, particularly with regards to forward speed. Even place a helicopter in the “compound” category, others after Igor Sikorsky perfected the now-classic configura- insist that it need only possess some form of augment- tion of a large single main rotor and a smaller anti- ed lift, or that it must have both. Focusing on what torque tail rotor a few years later, speed was still limited could be called “propulsive compounds,” the following in comparison to that of the helicopter’s fixed-wing pages provide a broad overview of the different helicop- brethren. Although Sikorsky’s basic design withstood ters that have been flown over the years with some sort the test of time and became the dominant helicopter of auxiliary propulsion unit: one or more propellers or configuration worldwide (approximately 95% today), jet engines. This survey also gives a brief look at the all helicopters currently in service suffer from one pri- ways in which different manufacturers have chosen to mary limitation: the inability to achieve forward speeds approach the problem of increased forward speed while much greater than 200 kt (230 mph). -

Naval Postgraduate School Thesis

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS A STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN ACQUISITION OF THE FRENCH MISTRAL AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT WARSHIPS by Patrick Thomas Baker June 2011 Thesis Advisor: Mikhail Tsypkin Second Reader: Douglas Porch Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2011 Master‘s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS A Study of the Russian Acquisition of the French Mistral Amphibious Assault Warships 6. AUTHOR(S) Patrick Thomas Baker 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING N/A AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

Helicopters in Combat: Methods for Helicopter Use in Special Operations

Review of the Air Force Academy No.1 (36)/2018 HELICOPTERS IN COMBAT: METHODS FOR HELICOPTER USE IN SPECIAL OPERATIONS Ioan MISCHIE Air Force Headquarters, Bucharest, Romania ([email protected]) DOI: 10.19062/1842-9238.2018.16.1.1 Abstract: The world is now marked by conventional and unconventional military actions, from classical armed confrontations, counterinsurgency, counter-terrorism to counter-act trafficking in human beings and drugs. In this wide range of actions, special operations play a particularly important role, solving sensitive issues in order to facilitate the achievement of political goals. These operations always begin with the action of introducing troops into the action area to carry out their missions. Helicopters are, by their characteristics, the means of transportation commonly preferred by commanders who plan and conduct such operations for the purpose of introducing, re-supplying, and extracting troops from the area of action. Keywords: special operations, helicopters, combat methods, high-value targets 1. INTRODUCTION Following World War II, lessons were learned, according to which the support of a classical war would have been costly, both economically and in terms of the loss of human lives, to resolve misunderstandings or confrontations between states, more emphasis has been put on the use of armed forces in atypical ways to carry out the armed struggle. In this way, it was intended to influence the opponent in order to impose its own goals, avoiding an open confrontation between states. In this new type of war, unconventional actions, meant to discredit and isolate the enemy on the international arena, have become increasingly important. -

Northwest District Fire and Aviation Aviation Plan

2019 BLM National Aviation Plan And Colorado State Aviation Plan And Northwest Colorado Fire and Aviation Management Unit Aviation Plan Prepared by: _James Michels________________ Date: __5/22/2019___ James Michels Unit AFMO/Unit Aviation Manager Reviewed by: ___ _____________ Date:_____________ Clark Hammond State Aviation Manager Reviewed by: ________________________________Date:______________ William Colt Mortenson Unit Fire Management Officer Approved by: _________________________________Date:______________ Andrew Archuleta BLM-Northwest District Manager The State Aviation plan, which was distributed via IM that was signed by the Associate State Director. The NWCFAMU will follow the Colorado State Aviation Plan and the National Aviation Plan as it is printed. Any areas that are more specific to NWCFAMU will be noted in red text inserted within the document. This plan was reviewed by the State Aviation Manager and noted that it is not less restrictive than the CO State Aviation Plan and there is no need for the plan to be signed as it is covered under the IM for. The Northwest Colorado Fire and Aviation Management Unit 455 Emerson Street Craig, CO 81625 The Table of Organization for Aviation within NWCFAMU: Unit Fire Management Officer o William Colt Mortenson : . w-(970) 826-5036 . c-(970) 367-6233 . [email protected] Unit Assistant Fire Management Officer/Unit Aviation Manager o James Michels . Meeker w-(970) 878-3821 . Craig w-(970) 826-5012 . c-(970) 749-7399 . [email protected] Cache Manager / SEAT Manager Trainee o Martin Martinez . w-(970) 826-5041 . c-(970) 761-3497 Craig Interagency Dispatch Center o (970) 826-5037 o [email protected] o Aviation Dispatcher Desk . -

Modernizing the AH-64 Tail Rotor

Proceedings of the 2020 Annual General Donald R. Keith Memorial Capstone Conference West Point, New York, USA April 30, 2020 A Regional Conference of the Society for Industrial and Systems Engineering Modernizing the AH-64 Tail Rotor Kelly Azinge, Cole Christiansen, Charles Moseley, Jay Peterson, Roderick Stoddard, and Michael Parrish Department of Systems Engineering United States Military Academy, West Point, NY Corresponding Author: [email protected] Author Note: The authors of this paper participated in a year-long senior project in the Department of Systems Engineering at the United States Military Academy (USMA). Pending graduation in May 2020, the authors will commission as Second Lieutenants in the United States Army as Aviation, Chemical, Engineer, and Field Artillery officers. This project was conducted under the advisement of Mr. Michael Parrish, who currently serves as an instructor at USMA. We would like to thank Mr. Matthew Sipe at PEO Aviation for his assistance with the project year-round in addition to Mr. Brad Paden at LaunchPoint Technologies for providing us with the e-TR system and report. Abstract: The United States Army is preparing to face near-peer threats with similar or better battlefield technology. This threat has driven a movement to modernize the force’s current battlefield systems. Future vertical lift ranks third on the Army’s list of modernization priorities. While the Army is preparing to acquire entirely new aircraft, the AH-64 Apache will remain an integral part of the fleet for the next 30 years. To maintain its relevance and improve its capabilities, the Army is evaluating the potential development of an electric tail rotor system to replace the current mechanically driven system. -

Helicopter Controllability. Reference 2 Presents a Comprehensive History and References 1 and 3 Present Summarized Histories of Helicopter Development

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1989-09 Helicopter controllability Carico, Dean Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27077 DTfltttf NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey , California THESIS C2D L/5~ HELICOPTER CONTROLLABILITY by Dean Carico September 1989 Thesis Advisor: George J. Thaler Approved for public release; distribution unlimited lclassified V CLASSi^'CATiON QF THIS PAGE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE ORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION 1b RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS assif ied IURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3 DISTRIBUTION /AVAILABILITY OF REPORT Approved for public release :lassification t DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE Distribution is unlimited ORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5 MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) ME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b OFFICE SYMBOL 7a. NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION il Postgraduate School (If applicable) 62 Naval Postgraduate School DRESS {City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b ADDRESS (C/fy, State, and ZIP Code) :erey, California 93943-5000 Monterey, California 93943-5000 9 PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER DRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS IE (include Security Claudication) HELICOPTER CONTROLLABILITY RSONAL AUTHOR(S) ICO, G. Dean YPE OF REPORT 4 DATE OF REPORT (Year, Month. Day) ter ' s Thesis 1989, September ipplementary notation T h e views expressed in this thesis are thos e of the hor and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department r,nyprninpnf npfpnsp nr ___ , COSATi CODES 18 SUBJECT TERMS {Continue on reverse if pecessary and identify Helicopter Controllability, Helicop Flight Control Systems, Helicopter Flying Qualities and Flying Qualities Spec if ications i 3STRACT {Continue I reverse if necessary and identify by block number) 'he concept of helicopter controllability is explained. -

Military Helicopter Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress

Order Code RL32447 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Military Helicopter Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress June 24, 2004 Christian F. M. Liles Research Associate Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Division Christopher Bolkcom Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Military Helicopter Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress Summary Recent military operations, particularly those in Afghanistan and Iraq, have brought to the fore a number of outstanding questions concerning helicopters in the U.S. armed forces, including deployability, safety, survivability, affordability, and operational effectiveness. These concerns are especially relevant, and made more complicated, in an age of “military transformation,” the “global war on terrorism,” and increasing pressure to rein in funding for the military, all of which provide contradictory pressures with regard to DOD’s large, and often complicated, military helicopter modernization efforts. Despite these questions, the military use of helicopters is likely to hold even, if not grow. This report includes a discussion of the evolving role of helicopters in military transformation. The Department of Defense (DOD) fields 10 different types of helicopters, which are largely of 1960s and 1970s design. This inventory numbers approximately 5,500 rotary-wing aircraft, not including an additional 144 belonging to the Coast Guard, and ranges from simple “utility” platforms such as the ubiquitous UH-1 “Huey” to highly-advanced, “multi-mission” platforms such as the Air Force’s MH- 53J “Pave Low” special operations helicopter and the still-developmental MV-22B “Osprey” tilt-rotor aircraft. Three general approaches can be taken to modernize DOD’s helicopter forces: upgrading current platforms, rebuilding current helicopter models (often called recapitalization), or procuring new models. -

Modeling Attack Helicopter Operations in Theater Level Simulations

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1996-06 Modeling attack helicopter operations in theater level simulations Hume, Robert S. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/32088 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS MODELING ATTACK HELICOPTER OPERATIONS IN THEATER LEVEL SIMULATIONS by Robert S. Hume June 1996 Thesis Advisor: Mark A. Youngren Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. DTIC QUALITY INBPE!JTED :5 19961024 033 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Fonn Approved OM:B No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. I. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 1996 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE MODELING ATTACK HELICOPTER 5. FUNDING NUMBERS OPERATIONS IN THEATER LEVEL SIMULATIONS 6. AUTHOR(S) Robert S. Hume 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION Monterey CA 93943-5000 REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S.