Voices Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecologies Everywhere the Green Smell of Cis-3-Hexanal

TCR THE CAPILANO REVIEW ecologies Everywhere the green smell of cis-3-hexanal. —Sonnet L’Abbé Editor Brook Houglum Web Editor Jenny Penberthy Managing Editor Tamara Lee The Capilano Press Colin Browne, Pierre Coupey, Roger Farr, Crystal Hurdle, Andrew Klobucar, Aurelea Society Board Mahood, Jenny Penberthy, Elizabeth Rains, Bob Sherrin, George Stanley, Sharon Thesen Contributing Art Editor Keith Wallace Contributing Editors Clint Burnham, Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson Founding Editor Pierre Coupey Designer Jan Westendorp Website Design Adam Jones Interns Iain Angus, Alexander McMillan, Teeanna Munro, Thomas Weideman The Capilano Review is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 hst included for individuals. Institutional rates are $35 plus hst. Outside Canada, add $5 and pay in U.S. funds. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC v7j 3h5. Subscribe online at www. thecapilanoreview.ca For our submission guidelines, please see our website or mail us an sase. Submissions must include an sase with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage or they will not be considered—do not use U.S. postage on the sase. The Capilano Review does not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, nor do we consider simultaneous submissions or previously published work; e-mail submissions are not considered. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. Please contact accesscopyright.ca for permissions. The Capilano Review gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the British Columbia Arts Council, Capilano University, and the Canada Council for the Arts. -

Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature

Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature by Ranbir Kaur Banwait M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2008 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Ranbir Kaur Banwait 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2014 Approval Name: Ranbir Kaur Banwait Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title of Thesis: Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Sean Zwagerman Associate Professor of English Dr. Christine Kim Co-Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor of English Dr. David Chariandy Co-Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of English Dr. Larissa Lai Associate Professor of English University of Calgary Dr. Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Dr. Donald Goellnicht External Examiner Professor of English and Cultural Studies McMaster University Date Defended/Approved: July 24, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract Histories of racialization in Canada are closely tied to the development of eugenics and racial hygiene movements, but also to broader concerns, expressed throughout Western modernity, regarding the “health” of nation states and their subjects. This dissertation analyses books by Velma Demerson, Hiromi Goto, David Chariandy, Rita Wong, Roy Miki and Larissa Lai to argue that Asian Canadian literature reveals, in heightened critical terms, how the politics of racial difference has -

Lai CV April 24 2018 Ucalg For

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Curriculum Vitae Date: April 2018 1. SURNAME: Lai FIRST NAME: Larissa MIDDLE NAME(S): -- 2. DEPARTMENT/SCHOOL: English 3. FACULTY: Arts 4. PRESENT RANK: Associate Professor/ CRC II SINCE: 2014 5. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates University of Calgary PhD English 2001 - 2006 University of East Anglia MA Creative Writing 2000 - 2001 University of British Columbia BA (Hon.) Sociology 1985 - 1990 Title of Dissertation and Name of Supervisor Dissertation: The “I” of the Storm: Practice, Subjectivity and Time Zones in Asian Canadian Writing Supervisor: Dr. Aruna Srivastava 6. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (a) University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates University of Calgary, Department of English Associate Professor/ CRC 2014-present II in Creative Writing University of British Columbia, Department of English Associate Professor 2014-2016 (on leave) University of British Columbia, Department of English Assistant Professor 2007-2014 University of British Columbia, Department of English SSHRC Postdoctoral 2006-2007 Fellow Simon Fraser University, Department of English Writer-in-Residence 2006 University of Calgary, Department of English Instructor 2005 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Instructor 2004 Clarion West, Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop Instructor 2004 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Teaching Assistant 2002-2004 University of Calgary, Department of English Teaching Assistant 2001-2002 Writers for Change, Asian Canadian Writers’ -

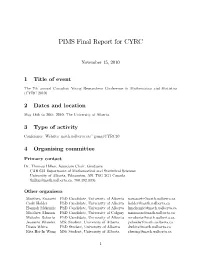

PIMS Final Report for CYRC

PIMS Final Report for CYRC November 15, 2010 1 Title of event The 7th annual Canadian Young Researchers Conference in Mathematics and Statistics (CYRC 2010) 2 Dates and location May 18th to 20th, 2010, The University of Alberta 3 Type of activity Conference. Website: math.ualberta.ca/~game/CYRC10 4 Organising committee Primary contact Dr. Thomas Hillen, Associate Chair, Graduate CAB 632 Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB. T6G 2G1 Canada [email protected], 780.492.3395 Other organisers Matthew Emmett PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Cody Holder PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Hannah Mckenzie PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Matthew Musson PhD Candidate, University of Calgary [email protected] Malcolm Roberts PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Jeanette Wheeler MSc Student, University of Alberta [email protected] Diana White PhD Student, University of Alberta [email protected] Rita Hei-In Wong MSc Student, University of Alberta [email protected] 1 5 Conference Summary The Canadian Young Researchers Conference in Mathematics and Statistics (CYRC) is an annual event that provides a unique forum for young mathematicians across Canada to present their research and to collaborate with their peers. All young academics involved in mathematics research were invited to give a scientific talk describing their work and to attend talks on a host of current research topics in mathematics and statistics. Participants had the opportunity to build and strengthen lasting personal and professional relationships, to develop and improve their communication skills, and gained valuable experience in the environment of a scientific conference. -

Autumn 2018 Vol. 32

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS FRANK ZAPPA A complete guide to his more than BC 100 recorded works. BOOKWORLD PAGE 25 VOL. 32 • NO. 3 • Autumn 2018 A darkly comedic memoir by Lindsay Wong NOT CRAZY RICH ASIANS See page 7 Avoid Screens FICTION: ILLUSTRATION: POLITICS: W.D. Valgardson’s Julie Flett reflects Christy Clark’s gothic crime on creating art for downfall is a PHOTO novel. picture books. political thriller. PAGE 28 PAGE 35 PAGE 10 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 SHIMON IMPROVING YOUR SEX LIFE WITH MINDFULNESS 15 9781459813335 9781459812871 “A magical encounter 9781459818194 “Plenty of with nature” 9781459819924 “Engaging and encouragement here.” —Kirkus Reviews An intimate look at the 9781459816503 triumphant.” —Booklist work of a world-renowned “Vibrant and engaging.” —CM Magazine artist and naturalist. —Kirkus Reviews Wade in the water and traipse through the trees. 9781459812734 9781459813458 9781459818019 “Eye-catching.” 9781459815131 “A calm, peaceful tone.” 9781459815865 “Entertaining.” —Kirkus Reviews “As magical as the —Kirkus Reviews “Concise and still —CM Magazine ocean itself.” thorough.” —Angie Abdou —Kirkus Reviews Find these and other great BC books at your local independent bookstore. 2 BC BOOKWORLD AUTUMN 2018 PEOPLE TOPSELLERS* Cyndi Suarez BCThe Power Manual: How to Master Complex Power Dynamics (New Society $19.99) Sophie Bienvenu translated by Rhonda Mullins Around Her (Talonbooks $19.95) Collin Varner The Flora and Fauna of Coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Heritage House $39.95) Sarah Cox Breaching the Peace: The Site C Dam and a Valley’s Stand against Big Hydro (UBC Press $24.95) Jen Currin PHOTO Hider/Seeker “It’s poetry’s uncanniness (Anvil Press $20) that attracts me.” SAWCHUK LORNA CROZIER LAURA “I come, after all, from a family of very ordinary, hard-working Richard Wagamese Saskatchewan people.” Richard Wagamese Indian Horse (D&M $21.95) NE OF THE FIRST PUBLIC EVENTS FOR ing the rent. -

Asian Canadian Studies Unfinished Projects

Guy Beauregard Asian Canadian Studies Unfinished Projects I In an essay that investigates “why interethnic antiracism matters now,” George Lipsitz asserts that “while ethnic studies is doing very well, ethnic people are faring very badly” (296). In making this assertion, Lipsitz seeks to identify and confront the implications of “the disparity between the sta- tus of ethnic studies and the status of ethnic communities” in the United States (296–97). He acknowledges that this disparity stems in part “from the personal failings of individual scholars, from the elitism and ideologi- cal conservatism at the core of academic career hierarchies, and from the isolation of many ethnic studies scholars from the activities of actual social movements” (297). But he also underlines that “the ethnic studies para- digm itself, as it has emerged historically, is also partly responsible for the problems we face” (197)—a point that has been addressed in a variety of ways by prominent ethnic studies scholars in the United States over the past twenty years (see, for example, Hirabayashi and Alquizola; Kim; and Omi). Particularly problematic for Lipsitz is what he calls “a one-group-at-a-time story of exclusion and discrimination rather than an analytic, comparative, and relational approach revealing injustice to be the rule rather than the exception in our society” (297). For Lipsitz, new forms of capitalist exploi- tation and new forms of racism in the postindustrial United States demand “new methods, theories, and strategies” to help us investigate what he calls “the interconnectedness of oppressions” (297). Lipsitz’s wake-up call, directed to scholars working in US ethnic studies, does not translate smoothly for scholars working on Asian Canadian top- ics. -

Countering Colonial Control: Imagining Environmental Justice and Reconciliation in Indigenous and Canadian Writer-Activism

Countering Colonial Control: Imagining Environmental Justice and Reconciliation in Indigenous and Canadian Writer-Activism by Alec Follett A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literary/Theatre Studies in English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Alec Follett, April, 2020 ABSTRACT COUNTERING COLONIAL CONTROL: IMAGINING ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION IN INDIGENOUS AND CANADIAN WRITER-ACTIVISM Alec Follett Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Jade Ferguson This dissertation considers the role of Indigenous knowledge in Joseph Boyden’s, Thomas King’s, and Rita Wong’s counter-discourse to the colonial control over Indigenous peoples’ land relations. Boyden, King, and Wong are part of a long history of Canadian and Indigenous writer- activists who have turned to literature to comment on the intertwined social and ecological violences caused by mapping colonial and capitalist relations onto Indigenous land; however, I argue that Boyden’s, King’s, and Wong’s early-twenty-first century writing has been constructed in relation to the notion of reconciliation. As such, their writing not only demonstrates that the recovery and enactment of Indigenous knowledge without interference from state, corporate, or settler actors is a precondition for environmental and epistemological justice, but also that justice requires the participation of non-Indigenous peoples who are willing to partake in non-colonial acts of relation building. In addition, I also address each writer-activist’s extra literary efforts— some of which have proved contentious. I argue that studying the strategies and challenges associated with their cultural work is necessary to develop a critical understanding of the complicated and influential figure of the writer-activist. -

Acknowledgement and Reciprocity With/In Indigenous and Asian Canadian Writing

In Place/Of Solidarity: Acknowledgement and Reciprocity with/in Indigenous and Asian Canadian Writing by Janey Mei-Jane Lew A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Sau-ling Wong, Chair Professor Colleen Lye Professor Beth Piatote Professor Shari Huhndorf Summer 2018 © 2018 Janey Mei-Jane Lew All rights reserved 1 ABSTRACT In Place/Of Solidarity: Acknowledgement and Reciprocity win/in Indigenous and Asian Canadian Writing by Janey Mei-Jane Lew Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Sau-ling Wong, Chair In Place/Of Solidarity argues the exigence of developing Asian Canadian critical praxes that align and move in solidarity with Indigenous sovereignties and radical resurgence movements. In the dissertation, I analyze a body of literary texts by contemporary Indigenous and Asian North American writers whose works contain instances of reciprocal representation. I argue that actions proceeding from and grounded in praxes of acknowledgement and reciprocity constitute openings to solidarity. By enacting Asian Canadian studies explicitly with decolonial solidarities in the foreground, I argue that Asian Canadian studies may not only work in ethical alignment with Indigenous knowledges and methodologies, but may also enliven and reconstitute the solidarities upon which Asian Canadian studies is premised. Bringing Asian Canadian studies into dialogue with scholarly work from Indigenous studies and recent research on Asian settler colonialism within a transnational Asian (North) American context, this dissertation considers reciprocal representations across a number of literary works by Indigenous and Asian Canadian women. -

Undercurrent by Rita Wong Kelly Shepherd UBC Okanagan

The Goose Volume 15 | No. 1 Article 6 8-21-2016 undercurrent by Rita Wong Kelly Shepherd UBC Okanagan Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Shepherd, Kelly. "undercurrent by Rita Wong." The Goose, vol. 15 , no. 1 , article 6, 2016, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol15/iss1/6. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Shepherd: undercurrent by Rita Wong A Call for Action, a Prayer to Hold On The poems of undercurrent are not as stylized, or cryptic, as those of Sybil undercurrent by RITA WONG Unrest (co-written with Larissa Lai in 2008); Nightwood Editions, 2015 $18.95 this book has more in common with 2007’s forage. Both are collage-like, with Reviewed by KELLY SHEPHERD illustrations and marginalia, and both employ a number of poetic forms. Some So terribly simple, so utterly undercurrent poems, like “fresh ancient unachieved so far: ground” (17) and “dada-thay” (70), to kick the oil addiction for love of juxtapose brief stanzas with essay-like water prose; repetition and rhythm are emphasized in “immersed” (32) and “#J28” . -

On Pedagogy and Social Justice in Asian Canadian Literature

ON PEDAGOGY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN ASIAN CANADIAN LITERATURE TEACHER, DETECTIVE, WITNESS, ACTIVIST: ON PEDAGOGY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN ASIAN CANADIAN LITERATURE By LISA KABESH, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Lisa Kabesh, July 2014 Lisa Kabesh — PhD Thesis — McMaster University — English & Cultural Studies DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JULY 2014 (English & Cultural Studies) HAMILTON, ON TITLE: Teacher, Detective, Witness, Activist: On Pedagogy and Social Justice in Asian Canadian Literature AUTHOR: Lisa Kabesh, B.A. (University of British Columbia), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Donald C. Goellnicht NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 231. ii Lisa Kabesh — PhD Thesis — McMaster University — English & Cultural Studies Abstract Teacher, Detective, Witness, Activist: On Pedagogy and Social Justice in Asian Canadian Literature undertakes a critical consideration of the relationship between pedagogy, social justice, and Asian Canadian literature. The project argues for a recognition of Asian Canadian literature as a creative site concerned with social justice that also productively and problematically becomes a tool in the pursuit of justice in literature classrooms of Canadian universities. The dissertation engages with the politics of reading and, by extension, of teaching social justice in the literature classroom through analyses of six high-profile, canonical works of Asian Canadian literature: Joy Kogawa’s Obasan (1981), SKY Lee’s Disappearing Moon Café (1990), Kerri Sakamoto’s The Electrical Field (1998), Madeleine Thien’s Certainty (2006), Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being (2013), and Rita Wong’s forage (2007). -

Fred Wah Fonds (Msc 17)

Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books Finding Aid - Fred Wah fonds (MsC 17) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.2.0 Printed: October 24, 2015 Language of description: English Rules for Archival Description Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books W.A.C. Bennett Library - Room 7100 Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby BC Canada V5A 1S6 Telephone: 778.782.8842 Email: [email protected] http://atom.archives.sfu.ca/index.php/fred-wah-fonds Fred Wah fonds Table of contents Summary information ........................................................................................................................ 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................... 3 Scope and content .............................................................................................................................. 4 Arrangement ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Notes ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Access points ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Series descriptions .............................................................................................................................. 6 -

Rita Wong and Larissa

Parliamentary Poet Laureate POETRY CONNECTION: LINK UP WITH CANADIAN POETRY Rita Wong (1968- ) grew up in Calgary, Alberta and currently lives in Vancouver, British Columbia where she is an assistant professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. She is the author of two books of poetry, monkeypuzzle (1998) and forage (2007). In 2011, forage won the Canada Reads Poetry competition. Wong's work investigates the relationships between social justice, ecology, decolonization (the dismantling of structures of power imposed by one set of people on another through colonialism), and contemporary poetics. She is especially interested in what she calls "the poetics of water," and works to educate her community on human interdependence with local water systems. She holds a PhD from Simon Fraser University. Larissa Lai (1967- ) was born in La Jolla, California and grew up in St. John's, Newfoundland. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the University of British Columbia. Her work brings her interests in feminism and Asian-Canadian identity together with her science fiction/fantasy imagination. Her first novel, When Fox Is a Thousand (1995) was shortlisted for the Chapters/Books in Canada First Novel Award. Among her works are a second novel, Salt Fish Girl (2002), and a solo book of poetry, Automaton Biographies (2009). She holds a PhD from the University of Calgary. Wong and Lai met in 1992, when they were both in their mid-twenties, on a bus to Orillia, Ontario. They were both headed to a conference on cultural appropriation. Wong had a list of Asian Canadian women writers she wanted to share with Lai.